Thread States: Life Cycle of a Thread

Thread States Life Cycle of a Thread

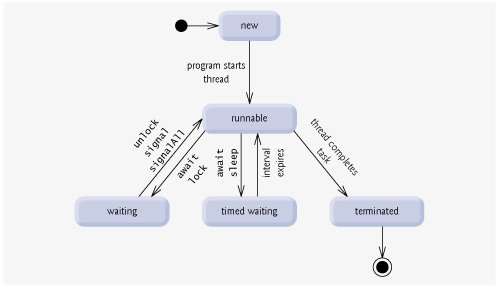

At any time, a thread is said to be in one of several thread states that are illustrated in the UML state diagram in Fig. 23.1. A few of the terms in the diagram are defined in later sections.

Figure 23.1. Thread life-cycle UML state diagram.

A new thread begins its life cycle in the new state. It remains in this state until the program starts the thread, which places the thread in the runnable state. A thread in this state is considered to be executing its task.

Sometimes a thread transitions to the waiting state while the thread waits for another thread to perform a task. Once in this state, a thread transitions back to the runnable state only when another thread signals the waiting thread to continue executing.

A runnable thread can enter the timed waiting state for a specified interval of time. A thread in this state transitions back to the runnable state when that time interval expires or when the event it is waiting for occurs. Timed waiting threads cannot use a processor, even if one is available. A thread can transition to the timed waiting state if it provides an optional wait interval when it is waiting for another thread to perform a task. Such a thread will return to the runnable state when it is signaled by another thread or when the timed interval expireswhichever comes first. Another way to place a thread in the timed waiting state is to put the thread to sleep. A sleeping thread remains in the timed waiting state for a designated period of time (called a sleep interval) at which point it returns to the runnable state. Threads sleep when they momentarily do not have work to perform. For example, a word processor may contain a thread that periodically writes a copy of the current document to disk for recovery purposes. If the thread did not sleep between successive backups, it would require a loop in which it continually tests whether it should write a copy of the document to disk. This loop would consume processor time without performing productive work, thus reducing system performance. In this case, it is more efficient for the thread to specify a sleep interval (equal to the period between successive backups) and enter the timed waiting state. This thread is returned to the runnable state when its sleep interval expires, at which point it writes a copy of the document to disk and reenters the timed waiting state.

A runnable thread enters the terminated state when it completes its task or otherwise terminates (perhaps due to an error condition). In the UML state diagram in Fig. 23.1, the terminated state is followed by the UML final state (the bull's-eye symbol) to indicate the end of the state transitions.

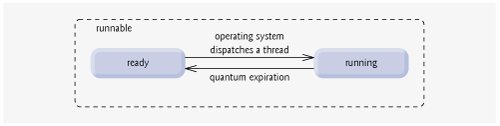

At the operating-system level, Java's runnable state actually encompasses two separate states (Fig. 23.2). The operating system hides these two states from the Java Virtual Machine (JVM), which only sees the runnable state. When a thread first transitions to the runnable state from the new state, the thread is in the ready state. A ready thread enters the running state (i.e., begins executing) when the operating system assigns the thread to a processoralso known as dispatching the thread. In most operating systems, each thread is given a small amount of processor timecalled a quantum or timeslicewith which to perform its task. When the thread's quantum expires, the thread returns to the ready state and the operating system assigns another thread to the processor (see Section 23.3). Transitions between these states are handled solely by the operating system. The JVM does not "see" these two statesit simply views a thread as being in the runnable state and leaves it up to the operating system to transition threads between the ready and running states. The process that an operating system uses to decide which thread to dispatch is known as thread scheduling and is dependent on thread priorities (discussed in the next section).

Figure 23.2. Operating system's internal view of Java's runnable state.

Introduction to Computers, the Internet and the World Wide Web

- Introduction

- What Is a Computer?

- Computer Organization

- Early Operating Systems

- Personal, Distributed and Client/Server Computing

- The Internet and the World Wide Web

- Machine Languages, Assembly Languages and High-Level Languages

- History of C and C++

- History of Java

- Java Class Libraries

- FORTRAN, COBOL, Pascal and Ada

- BASIC, Visual Basic, Visual C++, C# and .NET

- Typical Java Development Environment

- Notes about Java and Java How to Program, Sixth Edition

- Test-Driving a Java Application

- Software Engineering Case Study: Introduction to Object Technology and the UML (Required)

- Wrap-Up

- Web Resources

- Summary

- Terminology

- Self-Review Exercises

- Exercises

Introduction to Java Applications

- Introduction

- First Program in Java: Printing a Line of Text

- Modifying Our First Java Program

- Displaying Text with printf

- Another Java Application: Adding Integers

- Memory Concepts

- Arithmetic

- Decision Making: Equality and Relational Operators

- (Optional) Software Engineering Case Study: Examining the Requirements Document

- Wrap-Up

- Summary

- Terminology

- Self-Review Exercises

- Exercises

Introduction to Classes and Objects

- Introduction

- Classes, Objects, Methods and Instance Variables

- Declaring a Class with a Method and Instantiating an Object of a Class

- Declaring a Method with a Parameter

- Instance Variables, set Methods and get Methods

- Primitive Types vs. Reference Types

- Initializing Objects with Constructors

- Floating-Point Numbers and Type double

- (Optional) GUI and Graphics Case Study: Using Dialog Boxes

- (Optional) Software Engineering Case Study: Identifying the Classes in a Requirements Document

- Wrap-Up

- Summary

- Terminology

- Self-Review Exercises

- Exercises

Control Statements: Part I

- Introduction

- Algorithms

- Pseudocode

- Control Structures

- if Single-Selection Statement

- if...else Double-Selection Statement

- while Repetition Statement

- Formulating Algorithms: Counter-Controlled Repetition

- Formulating Algorithms: Sentinel-Controlled Repetition

- Formulating Algorithms: Nested Control Statements

- Compound Assignment Operators

- Increment and Decrement Operators

- Primitive Types

- (Optional) GUI and Graphics Case Study: Creating Simple Drawings

- (Optional) Software Engineering Case Study: Identifying Class Attributes

- Wrap-Up

- Summary

- Terminology

- Self-Review Exercises

- Exercises

Control Statements: Part 2

- Introduction

- Essentials of Counter-Controlled Repetition

- for Repetition Statement

- Examples Using the for Statement

- do...while Repetition Statement

- switch Multiple-Selection Statement

- break and continue Statements

- Logical Operators

- Structured Programming Summary

- (Optional) GUI and Graphics Case Study: Drawing Rectangles and Ovals

- (Optional) Software Engineering Case Study: Identifying Objects States and Activities

- Wrap-Up

- Summary

- Terminology

- Self-Review Exercises

- Exercises

Methods: A Deeper Look

- Introduction

- Program Modules in Java

- static Methods, static Fields and Class Math

- Declaring Methods with Multiple Parameters

- Notes on Declaring and Using Methods

- Method Call Stack and Activation Records

- Argument Promotion and Casting

- Java API Packages

- Case Study: Random-Number Generation

- Case Study: A Game of Chance (Introducing Enumerations)

- Scope of Declarations

- Method Overloading

- (Optional) GUI and Graphics Case Study: Colors and Filled Shapes

- (Optional) Software Engineering Case Study: Identifying Class Operations

- Wrap-Up

- Summary

- Terminology

- Self-Review Exercises

- Exercises

Arrays

- Introduction

- Arrays

- Declaring and Creating Arrays

- Examples Using Arrays

- Case Study: Card Shuffling and Dealing Simulation

- Enhanced for Statement

- Passing Arrays to Methods

- Case Study: Class GradeBook Using an Array to Store Grades

- Multidimensional Arrays

- Case Study: Class GradeBook Using a Two-Dimensional Array

- Variable-Length Argument Lists

- Using Command-Line Arguments

- (Optional) GUI and Graphics Case Study: Drawing Arcs

- (Optional) Software Engineering Case Study: Collaboration Among Objects

- Wrap-Up

- Summary

- Terminology

- Self-Review Exercises

- Exercises

- Special Section: Building Your Own Computer

Classes and Objects: A Deeper Look

- Introduction

- Time Class Case Study

- Controlling Access to Members

- Referring to the Current Objects Members with the this Reference

- Time Class Case Study: Overloaded Constructors

- Default and No-Argument Constructors

- Notes on Set and Get Methods

- Composition

- Enumerations

- Garbage Collection and Method finalize

- static Class Members

- static Import

- final Instance Variables

- Software Reusability

- Data Abstraction and Encapsulation

- Time Class Case Study: Creating Packages

- Package Access

- (Optional) GUI and Graphics Case Study: Using Objects with Graphics

- (Optional) Software Engineering Case Study: Starting to Program the Classes of the ATM System

- Wrap-Up

- Summary

- Terminology

- Self-Review Exercises

- Exercises

Object-Oriented Programming: Inheritance

- Introduction

- Superclasses and Subclasses

- protected Members

- Relationship between Superclasses and Subclasses

- Constructors in Subclasses

- Software Engineering with Inheritance

- Object Class

- (Optional) GUI and Graphics Case Study: Displaying Text and Images Using Labels

- Wrap-Up

- Summary

- Terminology

- Self-Review Exercises

- Exercises

Object-Oriented Programming: Polymorphism

- Introduction

- Polymorphism Examples

- Demonstrating Polymorphic Behavior

- Abstract Classes and Methods

- Case Study: Payroll System Using Polymorphism

- final Methods and Classes

- Case Study: Creating and Using Interfaces

- (Optional) GUI and Graphics Case Study: Drawing with Polymorphism

- (Optional) Software Engineering Case Study: Incorporating Inheritance into the ATM System

- Wrap-Up

- Summary

- Terminology

- Self-Review Exercises

- Exercises

GUI Components: Part 1

- Introduction

- Simple GUI-Based Input/Output with JOptionPane

- Overview of Swing Components

- Displaying Text and Images in a Window

- Text Fields and an Introduction to Event Handling with Nested Classes

- Common GUI Event Types and Listener Interfaces

- How Event Handling Works

- JButton

- Buttons that Maintain State

- JComboBox and Using an Anonymous Inner Class for Event Handling

- JList

- Multiple-Selection Lists

- Mouse Event Handling

- Adapter Classes

- JPanel Subclass for Drawing with the Mouse

- Key-Event Handling

- Layout Managers

- Using Panels to Manage More Complex Layouts

- JTextArea

- Wrap-Up

- Summary

- Terminology

- Self-Review Exercises

- Exercises

Graphics and Java 2D™

- Introduction

- Graphics Contexts and Graphics Objects

- Color Control

- Font Control

- Drawing Lines, Rectangles and Ovals

- Drawing Arcs

- Drawing Polygons and Polylines

- Java 2D API

- Wrap-Up

- Summary

- Terminology

- Self-Review Exercises

- Exercises

Exception Handling

- Introduction

- Exception-Handling Overview

- Example: Divide By Zero Without Exception Handling

- Example: Handling ArithmeticExceptions and InputMismatchExceptions

- When to Use Exception Handling

- Java Exception Hierarchy

- finally block

- Stack Unwinding

- printStackTrace, getStackTrace and getMessage

- Chained Exceptions

- Declaring New Exception Types

- Preconditions and Postconditions

- Assertions

- Wrap-Up

- Summary

- Terminology

- Self-Review Exercises

- Exercises

Files and Streams

- Introduction

- Data Hierarchy

- Files and Streams

- Class File

- Sequential-Access Text Files

- Object Serialization

- Random-Access Files

- Additional java.io Classes

- Opening Files with JFileChooser

- Wrap-Up

- Summary

- Terminology

- Self-Review Exercises

- Exercises

Recursion

- Introduction

- Recursion Concepts

- Example Using Recursion: Factorials

- Example Using Recursion: Fibonacci Series

- Recursion and the Method Call Stack

- Recursion vs. Iteration

- String Permutations

- Towers of Hanoi

- Fractals

- Recursive Backtracking

- Wrap-Up

- Internet and Web Resources

- Summary

- Terminology

- Self-Review Exercises

- Exercises

Searching and Sorting

- Introduction

- Searching Algorithms

- Sorting Algorithms

- Invariants

- Wrap-up

- Summary

- Terminology

- Self-Review Exercises

- Exercises

Data Structures

- Introduction

- Type-Wrapper Classes for Primitive Types

- Autoboxing and Auto-Unboxing

- Self-Referential Classes

- Dynamic Memory Allocation

- Linked Lists

- Stacks

- Queues

- Trees

- Wrap-Up

- Summary

- Terminology

- Self-Review Exercises

- Exercises

- Special Section: Building Your Own Compiler

Generics

- Introduction

- Motivation for Generic Methods

- Generic Methods: Implementation and Compile-Time Translation

- Additional Compile-Time Translation Issues: Methods That Use a Type Parameter as the Return Type

- Overloading Generic Methods

- Generic Classes

- Raw Types

- Wildcards in Methods That Accept Type Parameters

- Generics and Inheritance: Notes

- Wrap-Up

- Internet and Web Resources

- Summary

- Terminology

- Self-Review Exercises

- Exercises

Collections

- Introduction

- Collections Overview

- Class Arrays

- Interface Collection and Class Collections

- Lists

- Collections Algorithms

- Stack Class of Package java.util

- Class PriorityQueue and Interface Queue

- Sets

- Maps

- Properties Class

- Synchronized Collections

- Unmodifiable Collections

- Abstract Implementations

- Wrap-Up

- Summary

- Terminology

- Self-Review Exercises

- Exercises

Introduction to Java Applets

- Introduction

- Sample Applets Provided with the JDK

- Simple Java Applet: Drawing a String

- Applet Life-Cycle Methods

- Initializing an Instance Variable with Method init

- Sandbox Security Model

- Internet and Web Resources

- Wrap-Up

- Summary

- Terminology

- Self-Review Exercises

- Exercises

Multimedia: Applets and Applications

- Introduction

- Loading, Displaying and Scaling Images

- Animating a Series of Images

- Image Maps

- Loading and Playing Audio Clips

- Playing Video and Other Media with Java Media Framework

- Wrap-Up

- Internet and Web Resources

- Summary

- Terminology

- Self-Review Exercises

- Exercises

- Special Section: Challenging Multimedia Projects

GUI Components: Part 2

- Introduction

- JSlider

- Windows: Additional Notes

- Using Menus with Frames

- JPopupMenu

- Pluggable Look-and-Feel

- JDesktopPane and JInternalFrame

- JTabbedPane

- Layout Managers: BoxLayout and GridBagLayout

- Wrap-Up

- Summary

- Terminology

- Self-Review Exercises

- Exercises

Multithreading

- Introduction

- Thread States: Life Cycle of a Thread

- Thread Priorities and Thread Scheduling

- Creating and Executing Threads

- Thread Synchronization

- Producer/Consumer Relationship without Synchronization

- Producer/Consumer Relationship with Synchronization

- Producer/Consumer Relationship: Circular Buffer

- Producer/Consumer Relationship: ArrayBlockingQueue

- Multithreading with GUI

- Other Classes and Interfaces in java.util.concurrent

- Monitors and Monitor Locks

- Wrap-Up

- Summary

- Terminology

- Self-Review Exercises

- Exercises

Networking

- Introduction

- Manipulating URLs

- Reading a File on a Web Server

- Establishing a Simple Server Using Stream Sockets

- Establishing a Simple Client Using Stream Sockets

- Client/Server Interaction with Stream Socket Connections

- Connectionless Client/Server Interaction with Datagrams

- Client/Server Tic-Tac-Toe Using a Multithreaded Server

- Security and the Network

- Case Study: DeitelMessenger Server and Client

- Wrap-Up

- Summary

- Terminology

- Self-Review Exercises

- Exercises

Accessing Databases with JDBC

- Introduction

- Relational Databases

- Relational Database Overview: The books Database

- SQL

- Instructions to install MySQL and MySQL Connector/J

- Instructions on Setting MySQL User Account

- Creating Database books in MySQL

- Manipulating Databases with JDBC

- Stored Procedures

- RowSet Interface

- Wrap-Up

- Internet and Web Resources

- Recommended Readings

- Summary

- Terminology

- Self-Review Exercises

- Exercises

Servlets

- Introduction

- Servlet Overview and Architecture

- Setting Up the Apache Tomcat Server

- Handling HTTP get Requests

- Handling HTTP get Requests Containing Data

- Handling HTTP post Requests

- Redirecting Requests to Other Resources

- Multitier Applications: Using JDBC from a Servlet

- Welcome Files

- Wrap-Up

- Internet and Web Resources

- Summary

- Terminology

- Self-Review Exercises

- Exercises

JavaServer Pages (JSP)

- Introduction

- JavaServer Pages Overview

- First JSP Example

- Implicit Objects

- Scripting

- Standard Actions

- Directives

- Case Study: Guest Book

- Wrap-Up

- Internet and Web Resources

- Summary

- Terminology

- Self-Review Exercises

- Exercises

Formatted Output

- Introduction

- Streams

- Formatting Output with printf

- Printing Integers

- Printing Floating-Point Numbers

- Printing Strings and Characters

- Printing Dates and Times

- Other Conversion Characters

- Printing with Field Widths and Precisions

- Using Flags in the printf Format String

- Printing with Argument Indices

- Printing Literals and Escape Sequences

- Formatting Output with Class Formatter

- Wrap-Up

- Summary

- Terminology

- Self-Review Exercises

- Exercises

Strings, Characters and Regular Expressions

- Introduction

- Fundamentals of Characters and Strings

- Class String

- Class StringBuffer

- Class Character

- Class StringTokenizer

- Regular Expressions, Class Pattern and Class Matcher

- Wrap-Up

- Summary

- Terminology

- Self-Review Exercises

- Exercises

- Special Section: Advanced String-Manipulation Exercises

- Special Section: Challenging String-Manipulation Projects

Appendix A. Operator Precedence Chart

Appendix B. ASCII Character Set

Appendix C. Keywords and Reserved Words

Appendix D. Primitive Types

Appendix E. (On CD) Number Systems

Appendix F. (On CD) Unicode®

Appendix G. Using the Java API Documentation

Appendix H. (On CD) Creating Documentation with javadoc

Appendix I. (On CD) Bit Manipulation

Appendix J. (On CD) ATM Case Study Code

Appendix K. (On CD) Labeled break and continue Statements

Appendix L. (On CD) UML 2: Additional Diagram Types

Appendix M. (On CD) Design Patterns

Appendix N. Using the Debugger

Inside Back Cover

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 615