Chapter III Two Models of Online Patronage: Why Do Consumers Shop on the Internet?

III Two Models ofOnline Patronage Why Do Consumers Shop on the Internet?

Yue Pan

University of Dayton, USA

George Zinkhan

University of Georgia, USA

Abstract

The Internet provides an alternative method for reaching retail consumers, and e-tailing is attracting considerable attention from practitioners and scholars. This chapter aims to develop a better understanding of Internet shopping (with a special emphasis on explaining consumer patronage behavior). Two conceptual models of consumer online patronage behavior are developed. Our focus is on the “C” side of B-to-C commerce. We do not deal explicitly with B-to-B commerce. Based on a review of the traditional retailing literature as well as the emerging e-commerce literature, we identify the promising predictor variables that may be applicable to the Internet setting. The outcome of our investigation is two conceptual models, including 22 propositions.

Introduction

For years, primary channels for electronic sales have been enabled through technologies such as telephone, fax, ATM, credit cards, or television. Recently, e-commerce (EC) has emerged as a growing force in the world economy, both in terms of communication opportunities and in terms of sales channels. Here, we define e-commerce as “the use of information technology to enhance communications and transactions with all of an organization’s stakeholders” (Watson et al., 2000, p. 1).

Shopping is increasingly popular on the Internet. For instance, consumers increased their online shopping by 46% in 2000, with sales for the year totaling $56 billion, according to a recent report from ActivMedia Research, an e-business information company. ActivMedia estimates that, as e-tailers continue to fine-tune their marketing and order processing, online sales for B-to-C marketers will reach one trillion dollars by 2010 (Scott, 2001). Almost 40 million Americans, or about 17% of the population, have made purchases online, and by 2010 B2C e-commerce may account for 15 to 20 percent of all United States retail sales (Peet, 2000).

Emerging technologies have touched off a revolution among conventional retailers who are now faced with a new transaction channel. In line with evolution in the marketplace, a recent Journal of Retailing editorial calls for papers that examine this increasingly important topic (Levy and Grewal, 2001). Marketing academicians have probed the topic of online shopping from different perspectives (see Table 3-1 for a summary of these studies). Previous research reveals some useful insights on the demographic, socioeconomic, and psychographic profiles of Internet shoppers. Some studies on consumer online choice behavior are descriptive in nature. Some have set forth explicit hypotheses regarding factors that influence online buying. Fewer attempts have been made to develop models of online buying. Few studies, if any, have made an elaborate attempt to relate the emerging e-tailing research to the extant research on traditional retailing. The current study seeks to conduct an extensive review of the relevant literature and to address such intuitively appealing issues as: What is the state of the art for the study of online patronage behavior? What are the relevant variables for explaining online shopping? To what extent are key theories about bricks-and-mortar retailing relevant for exploring patronage behavior in an online setting?

|

Author |

Publication |

Study Design/Data Source |

Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Donthu and Garcia, 1999 |

Journal of Advertising Research |

Telephone survey of 790 people |

Internet shoppers are older and make more money than non-shoppers. Internet shoppers are more convenience seekers, innovative, impulsive, variety seekers, and less risk averse than non-shoppers are. Internet shoppers are also less brand and price conscious than nonshoppers are. Internet shoppers have a more positive attitude toward advertising and direct marketing than non-shoppers do. |

|

Lohse and Spiller, 1999 |

Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication |

28 online retail stores |

The study analyzes the impact of some Web site features (e.g., FAQ section, browsing and navigation capabilities, number of store entrances, appetizer information) on store traffic and sales. |

|

Lin, 1999 |

Journal of Advertising Research |

A telephone survey using random digit dialing with 348 participants |

Motives for online service use (i.e., surveillance, entertainment, and escape/companionship/identity) are significant predictors for likely online-service adoption. |

|

Li, Kuo, and Russell, 1999 |

Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication |

Online survey of 999 US Internet users |

Channel knowledge, perceptions of channel utilities, convenience orientation, experiential orientation, income, education, and gender are predictors in the model of online buying behavior. |

|

Jarvenpaa et al., 1999 |

Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication |

Survey |

Favorable attitudes towards an Internet store and reduced perceived risks associated with buying from an Internet store will increase the consumer’s willingness to purchase from that Internet store. |

|

Korgaonkar and Wolin, 1999 |

Journal of Advertising Research |

Interviews of Web users |

Online shoppers and non-shoppers are compared with respect to their motivations and demographics. |

|

Swaminathan, Lepkowska-White, and Rao, 1999 |

Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication |

Georgia Tech GVU online survey |

Perceived superiority of Web vendors (e.g., reliability of a vendor, convenience of placing order and contacting vendors, price competitiveness and access to information) positively affects frequency of consumer shopping on the Internet. |

|

Lohse, Bellman, and Johnson, 2000 |

Journal of Interactive Marketing |

9738 panelists from Wharton Virtual Test Market survey panel |

The demographics and Internet usage are used to predict who are buying online, and how much they spend. |

|

Degeratu, Rangaswamy, and Wu, 2000 |

International Journal of Research in Marketing |

Datasets from Peapod (where about 300 subscribers were tracked) and IRI for 1039 panelists |

The impact of brand names and sensory search attributes on choices online is examined. |

|

Haubl and Trifts, 2000 |

Marketing Science |

Experiment |

The study analyzes the effects of two decision aids on purchase decision making in an online store. |

|

Miyazaki and Fernandez, 2001 |

Journal of Consumer Affairs |

Survey with a sample size of 160 Internet users |

Perceived risk, security concerns, Internet experiences, and the adoption of established methods for remote retail purchase transactions are found to be associated with the online purchase rate. |

|

Shim et al., 2001 |

Journal of Retailing |

Mail survey to computer users |

Intention to use the Internet to search for information is the strongest predictor of Internet purchase intention. It mediates relationships between purchasing intention and other predictors (i.e., attitude toward Internet shopping, perceived behavioral control, and previous Internet purchase experience). |

|

Childers et al., 2001 |

Journal of Retailing |

Experiments |

Motivations to engage in retail shopping include both utilitarian and hedonic dimensions. |

|

Levy, 2001 |

ACR |

Case study featuring one online shopper |

The superiority of online shopping is shown in savings of time, money, and in providing a variety of other consumer satisfaction. |

|

Lynch, Kent, and Srinivasan, 2001 |

Journal of Advertising Research |

Experiments conducted in 12 countries with a total of 299 subjects |

Three characteristics (site quality, affect, and trust) significantly affect consumers’ purchase behavior. |

|

Mathwick, Malhotra, and Rigdon, 2001 |

Journal of Retailing |

Mail survey of 213 Internet shoppers |

An experiential value scale reflecting the benefits derived from perceptions of playfulness, aesthetics, customer “return on investment” and service excellence is developed in the Internet shopping context. |

|

Liao and Cheung, 2001 |

Information & Management |

Survey |

The life content of products, transactions security, price, vendor quality, IT education and Internet usage significantly affect the initial willingness of Singaporeans to e-shop on the Internet. |

|

Mathwick, 2002 |

Journal of Interactive Marketing |

GVU online survey data |

The study classifies online shoppers with relational norms (e.g., behavior loyalty, contract barriers, continuity barriers, effort, enjoyment, entertainment, escapism). |

|

Goldsmith, 2002 |

Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice |

Survey of 107 undergraduates |

Frequency of online buying and intent to buy online in the future are predicted by general innovativeness, an innovative predisposition toward buying online, and involvement with the Internet. |

|

Menon and Kahn, 2002 |

Journal of Retailing |

Experiment |

The characteristics of products and Web sites encountered earlier can significantly influence consumers’ later shopping behavior. |

|

Menon and Kahn, 2002 |

Journal of Retailing |

Experiment |

The effect of arousal and pleasure on shopping behavior was examined. |

|

Forsythe and Shi, 2003 |

Journal of Business Research |

GVU online survey data |

This study examined the nature of perceived risks associated with Internet shopping and the relationship between types of risk perceived by Internet shoppers and their online patronage behaviors. |

The study is stimulated by the managerial needs to understand why consumers buy online so that marketers can develop effective strategies to increase store traffic and online sales. The study has implications for marketing academics as well. Previous researchers have been investigating the antecedents of choice behavior in a traditional retailing context for decades. The effect of various correlates of retail patronage is well researched theoretically as well as empirically. Compared to its bricks-and-mortar counterpart, e-tailing research is relatively new and awaits more rigorous studies. It is of intuitive appeal to close the gap between what we know about online patronage from two streams of research: the emerging e-commerce research and the extant traditional retailing research. We propose in this study that many of the “old” variables under study for decades may shed light on our current research on e-tailing.

The overall objective of this chapter is to develop a better understanding of Internet shopping, based on a review of the extant retailing literature and the emerging EC literature. We are interested to see the extent to which the two research streams generate alternative (or complementary) models, and we attempt to determine the extent to which existing retailing theories can be adapted to cyberspace.

Conceptual Framework

In this section, we first attempt to explore the extent to which key theories derived from bricks-and-mortar retailing are relevant for exploring patronage behavior in an online setting. We draw from the extant literature on conventional modes of shopping and identify factors that predict consumers’ online patronage behavior. Then, we propose a competing model based on the EC research.

The key dependent variable in both models is defined as “the probability of consumers’ online shopping (i.e., purchasing).” In describing our dependent variable, we use the following terms as synonyms: (a) probability of online shopping; (b) likelihood of being an Internet shopper. In this chapter, an Internet shopper is defined as a consumer who has access to the Internet and has previous experiences with the Internet (but not necessarily shopping experiences). That is, we assume that the individual consumer in our model has access and inclination to use the Internet. Our focus is on B-to-C commerce.

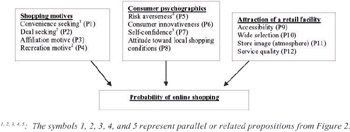

Figure 3-1: Proposed model of online patronage (given that consumers have Internet access and experiences)

Model Developed from Traditional Retailing Literature

A conceptual model is forged on the basis of our learning from traditional retailing theory and practice (Figure 3-1). Prospective predictor variables are chosen if they are considered important in explaining retail patronage in an offline setting. Three factors (i.e., shopping motives, consumer psychographics, attraction of a retail facility) are identified as the key determinants of online patronage. The propositions that are represented in the model are described in more detail later. The model assumes that consumers have access to the Internet and have prior online experiences.

Shopping Motives

There are a variety of extant models to explain shopping behavior and its underlying motivations. A unified, comprehensive framework has much to offer in guiding retail strategy formulation, and it also advances efforts to develop more comprehensive theories of shopping behavior.

Shopping motives are “all those impulses, desires, and considerations of the customer that induce the purchase of certain goods and services” (Udell, 1964-1965, p. 8). They account for the underlying reasons why people buy what they buy. Motivational theorists have typically regarded human behavior as the product of both internal need states and external stimuli perceived by the individual (Westbrook and Black, 1985). Numerous attempts have been made to classify and organize the diversity of shopping motives (e.g., Stone, 1954; Tauber, 1972; Westbrook and Black, 1985). Regardless of classification, however, it is commonly agreed that the consummation of motive provides subjective gratification, or satisfaction, to the individual. Thus, the motives represent a useful indicator of resulting behaviors. A vast array of motives has been proposed, with varying degrees of focus and specificity.

Economic Motivation

From an “economic man” perspective, a shopper will minimize the time required to accomplish the needed shopping task. That is, there is a motivation to conserve resources. Some shoppers and some shopping trips undoubtedly conform to this notion of resource conservation notion. Bellenger and his colleagues (Bellenger, Robertson, and Greenberg, 1977; Bellenger and Korgaonkar, 1980) classify shoppers, according to their shopping motivations, into two broad categories: “functional-economic” and “recreational” shoppers. The two shopper types differ in the amount of time and information-seeking involved in shopping. Convenience and economic shoppers dislike shopping or are neutral toward it, and thus approach retail store selection from a time- or money-saving point of view. Using a more extensive typology of shopping motivation, Westbrook and Black (1985) identify economic role enactment, choice optimization and negotiation, which are all economically based motives. Shoppers with choice optimization motivation, for example, are finding exactly what they want to acquire in the least amount of time. The utility of an acquisition is enhanced if it is obtained with minimal search effort.

- Convenience Seeking: Consumers perceive convenience in product acquisition as a major advantage associated with in-home shopping (Darian, 1987; Gillett, 1970). This economic orientation is expressed both in the desire for convenience (to lower the search cost and to limit the shopping time) and for lower prices. By making a shopping trip only when he knows specific buying objective can be met, the functional-economic shopper optimizes choice and increases the net utility of an acquisition. Store quality, variety, and related services are secondary considerations to perceived convenience and other economic advantages of the store.

Consumers are more likely to shop at home for two main reasons: motivators (e.g., the need to save time) and facilitators (e.g., a dislike of in-store shopping) (Darian, 1987). We speculate that there are two major types of convenience that shoppers seek when choosing from their consideration set of stores: (1) savings in time and flexibility in time management; and (2) trouble/problem minimization during a transaction. Darian (1987) and Graham (1981) use a time management explanation for shoppers’ patronage behavior. For instance, in-home shopping can reduce the time spent as well as provide flexible timing for shopping.

Convenience seekers may also be inclined to bypass the trouble associated with offline shopping. There are types of convenience that in-home shoppers could be seeking (e.g., saving the physical effort of visiting stores, saving of aggravation) (Darian, 1987). Considering Internet shopping as a new alternative for in-home shopping, Internet shoppers could receive many of the benefits described by Darian. The typical popularity of the Internet can be partially attributed to the ease with which customers can sift through vast amounts of information. The Internet brings the marketplace to the consumer, who can purchase virtually anything ranging from groceries to cars. Competing businesses in the world of electronic commerce are only a few mouse clicks away. Thus, there is the potential for shopping to become less time consuming. It also eliminates the worry and hassles associated with traffic, travel, and parking. Therefore, we offer the following proposition:

P1: Consumers’ desire for convenience enhances the probability of online shopping.

- Deal seeking: Another factor that leads shoppers to a store is the offer of price promotions. Various scholars (e.g., Blattberg, Buesing, and Peacock, 1978; Lichtenstein, Netemeyer, and Burton, 1990) find a segment of consumers who are deal-prone. This group of shoppers is typically value-conscious and sensitive to premium offers. The Internet mimics a giant-sized shopping center in the sense that many product categories (virtually anything ranging from cars to groceries) and brands are available. Price competition on the Web is perceived to be more intense than in the on-ground marketplace, as consumers’ search cost is substantially reduced. Price search and price comparison can be done almost effortlessly. Various search engines, shopping bots and intelligent agents (e.g., Copernic Shopper, DealCatcher) allow users to surf a plethora of bargains within seconds. Therefore, deal prone consumers are likely to shop on the Internet. Thus, we propose that:

P2: Consumers who like to search for deals are more likely to be Internet shoppers.

Non-Economic Motivation

Hedonistic motives can be important precursors of consumer behavior (Halvena and Holbrook, 1986; Hirschman and Holbrook, 1982). Bellenger and Korgaonkar’s (1980) twofold shopper typology differentiates the recreational shopper from the more functional-economic shopper. Unlike functional shoppers, recreational shoppers are individuals who shop for the pleasure of the shopping experience itself. Recreational shoppers enjoy shopping as a leisure activity, shop impulsively, place higher importance on store décor, spend more time shopping per trip, continue shopping after making a purchase, and prefer closed malls and department stores (Bellenger and Korgaonkar, 1980). Convenience and economic issues are not the primary concern for this shopper segment.

- Consumers’ Affiliation Motive: McClelland’s theory on human motivations defines the affiliation motive as the need to be with people (McClelland, 1987). One of the most basic social behaviors is the urge for human contact and connection. That is, people experience a strong motivation to associate themselves meaningfully with groups of kindred spirits in order to reduce feelings of boredom and loneliness. An important issue in the study of loneliness concerns the strategies that people adopt in order to cope with and alleviate their feelings of loneliness. “Going shopping” is one such activity that people pursue (Graham, 1988; Rubenstein and Shaver, 1980). Shopping centers and malls offer opportunities to drown out problems. Malls offer escape (i.e., relief from boredom, escape from routine, and high levels of sensory stimulation) (Bloch, Ridgway, and Dawson, 1994). On-ground retail stores also offer a chance for human interactions, that is, some consumers enjoy talking to and socializing with others during a shopping visit, and they are seeking “social experience outside the home” (Tauber, 1972). Some of this interaction is with fellow shoppers and some is with sales personnel (Donovan and Rossiter, 1982). Because of the multiple opportunities for social interactions, some consumers are reluctant to patronize nontraditional retailers (e.g., catalog shopping, home computerized shopping, television shopping).

Non-store retailers may inadvertently create a sense of isolation and a feeling of loneliness among their customers (Farmer, 1988). Even though technological innovations may potentially create consumer advantages (e.g., speed, accuracy, economy, convenience), they have the effect of insulating and detaching consumers from their fellows. In an attempt to offset this isolating effect, some e-stores strive to create communal effects by fostering community sentiments and encouraging collective action. Nonetheless, one can argue that compared with the Internet, brick-and-mortar stores offer greater opportunities to socialize due to the presence of physical surroundings and face-to-face interactions. Hence, we have:

P3: Need for affiliation (i.e., consumers’ need to socialize) has a negative influence on the probability for online shopping.

- Shopping Pleasure: Personal motives are influential in shopping behavior. Among the most prominent satisfactions obtained from shopping include: (1) experiencing self-gratification; (2) learning new trends; (3) experiencing physical exercise; and

(4) receiving sensory stimulation from the retail environment. A desire for power, authority over salespeople, and stimulation from the shopping environment are related experiences (Westbrook and Black, 1985). Recreational shoppers do not view store shopping as a waste of time (Sproles and Kendall, 1986). Instead, they shop with a feeling of gratification, fulfillment, and satisfaction.Arousal induced by the store environment would intensify pleasure or displeasure such that time and spending behavior would be increased in pleasant environments and decreased in unpleasant environments (Donovan et al., 1994). Malls are viewed by consumers as a place not only for shopping, but also for other activities, such as entertainment (Bloch et al., 1994). A number of other studies argue that the central reason many people visit malls is for the excitement of the experience (e.g., Cockerham, 1995; Graham, 1988; Stoltman, Gentry, and Anglin, 1991). As opposed to bricks-and-mortar store shopping, online shopping cannot satisfy the desire for immediate gratification. Moreover, the inability for consumers to physically inspect products and the absence of sensory stimulation from the store environment may drive some consumers away from the virtual marketplace. Hence:

P4: Recreational shoppers are less likely to be Internet shoppers.

Consumer Psychographics

Psychographic segmentation may provide a more refined tool for the understanding of shopping behavior (Darden and Perrault, 1976). However, the relationship between psychographic characteristics and adoption of emerging retailing alternative (e.g., the Internet) is not expected to be strong, since a substantial body of research has found that although some relationships between personality characteristics and purchase behaviors are statistically significant, they are small in magnitude (Kassarjian, 1971).

Risk Averseness

The willingness to purchase products is inversely related to the type and amount of perceived risk associated with a purchase decision (Bauer, 1960; Bettman, 1973, 1975; Korgaonkar, 1982; Peter and Tarpey, 1975). A number of risk facets have been identified as potential inhibitors to purchase. These dimensions include: performance, social, psychological, convenience, physical, and financial risks (Jacoby, Kaplan, and Szybillo, 1974; Peter and Tarpey, 1975; Peter and Ryan, 1976). In-home shoppers tend to be more adventurous, cosmopolitan and self-confident in their shopping behavior (Cunningham and Cunningham, 1973; Gillett, 1976). As predicted by these studies, Internet shoppers, as one group of in-home shoppers, should be more tolerant of purchase risk than store patrons. We therefore propose that:

P5: Risk averse consumers are less likely to shop on the Internet than those who are risk takers.

Consumer Innovativeness

Here, consumer innovativeness is defined as the degree to which consumers possess a favorable attitude towards trying new ideas or different practices. At the most basic level, this preference motivates a search for new experiences that stimulate the mind and/or the senses (Hirschman, 1984; Pearson, 1970; Venkatraman and Price, 1990). Outshoppers (i.e., people who shop outside their residential areas) tend to be more innovative and to know more about the world outside their community (King, 1965). Cognitive innovators (who prefer new experiences that stimulate the mind) are thinkers and problem solvers (Venkatraman, 1991). Since they seek new experiences, they are likely to consider newness of the innovation important in the purchase decision.

The Internet, as an emerging mode of retailing, has characteristics very different from more traditional retail operations (e.g., it creates remote buying experiences; computerized transaction empowers the consumer with a sense of control). Because of this “freshness,” it tends to attract innovative consumers. Therefore, we propose that:

P6: Innovative consumers are more likely to shop on the Internet.

Self-Confidence

In marketing, the traditional retailing literature identifies self-confidence as a predictor variable for consumer shopping-channel choice. Boone (1974) posits that innovative buyers have greater self-confidence. His finding is supported by Reynolds (1974), who finds that self-confident people tend to shop more frequently at home. In-home shoppers belong to a higher-than-average socio-economic group, measured by education, income, social class, and occupational status (Gillett, 1976; Salste, 1996). These socio-economic differences may become especially pronounced among Internet shoppers, who are more willing to take risks and try new things and less conservative than their store-prone counterparts. In an online setting, shoppers do not have face-to-face interaction with a salesperson. The resulting lack of real-time service and help, in a sense, demands consumers to be self-reliant. Hence:

P7: The higher a consumer’s self-confidence, the more likely that consumer is to shop on the Internet.

Attitude Toward Local Shopping Conditions

Out-shopping behavior is determined by unique socioeconomic, lifestyle, and economic factors, as well as by the quality of local retail facilities (Darden, Lennon, and Darden, 1978). Attitude about local shopping (i.e., shopping within the consumer’s residential area) is the most salient psychographic variable in differentiating between different patronage groups. The typical out-shopper is seen as an innovator, an on-the-go, cosmopolitan person who is generally dissatisfied with local retail facilities (Papadopoulos, 1980). Consumers who are expected to benefit from in-home shopping are those who have difficulty getting to local stores or who have limited local retail facilities (Berkowitz, Walton, and Walker, 1979; Cox and Rich, 1964). People in these circumstances are more likely to shop at home. Samli and Uhr (1974) find that moving across the spectrum from loyal in-shoppers to heavy out-shoppers indicates that the level of satisfaction with the following characteristics of local shopping facilities decreases: quality, selection, prices of goods offered; courtesy, product knowledge of salespeople; ease of shopping; appearance of retail facilities; and store hours of retail facilities.

Internet shoppers, unrestricted by geographical boundaries, are essentially one type of out-shoppers, i.e., consumers who shop outside the residents’ trading area. Based on the above discussion, local retailing inadequacies may prompt out-shopping such as Internet shopping. For instance, shoppers may want to avoid some of the unpleasant aspects of shopping in stores by turning to another trading alternative — online shopping. The advantages of Internet buying must outweigh those of the customary methods of local shopping, at least from Internet shoppers’ perspective. Hence:

P8: Negative attitudes toward local shopping conditions enhance the probability of online shopping.

Attraction of a Retail Facility

Location: Location Theory

In the traditional retailing literature, location has always been treated as an important factor in attracting patrons to a shopping area. The most widely accepted location theory is central place theory (Craig, Ghosh, and McLafferty, 1984), which views shopping areas as commerce centers to which consumer households travel to obtain needed goods and services. Generally speaking, central business districts and regional shopping centers that offer higher-order goods and services or an agglomeration of both attract customers from greater distances than neighborhood centers that offer only lower-order goods and services. Customers seeking to maximize their shopping time will often drive past weaker malls to reach destination malls that have the best variety of stores and merchandise (Ashley, 1997). The breadth (number of brands) and depth of assortment (number of stock-keeping units) offered in a shopping center helps a retailer to cater to the heterogeneous tastes of his customers (Dhar, Hoch, and Kumar, 2001). Offering more variety can help a retailer attract more consumers to visit the store as well as entice them to make purchases in the store. Research based on central place theory employs economic utility models that incorporate factors such as distance or travel time and the size of a center to express the relationship between costs and benefits of shopping area choice (Ghosh, 1986; Huff, 1962; Louviere and Gaeth, 1987; Weisbrod, Parcells, and Kern, 1984). A central place can reduce the transaction cost associated with a shopping visit (e.g., transportation cost, time spent on shopping). The Internet is very often likened to a virtual shopping center which is easily accessible, especially for consumers in geographically restricted areas. The ability to purchase virtually anything ranging from groceries to cars, the ease and convenience of shopping from home at any time of day are appealing allurements for shoppers. Therefore, the Internet has the characteristics of a central shopping area with a wide selection of products. Based on the central place theory, we propose that:

P9: A sizeable segment of consumers perceive the Internet to be an easily accessible (e.g., by offering savings in travel time) shopping channel. This perception enhances the likelihood of online shopping.

P10: A sizeable segment of consumers perceive the Internet to be a central shopping location that offers a wide selection of goods. This perception enhances the likelihood of online shopping.

In addition, we propose that there is an online parallel to the central shopping mall. For instance, some online organizations are perceived to be “centrally located” in virtual space (e.g., those retailing sites associated with popular Web portals such as AOL or Yahoo!). Also, some sites are more easily accessible by popular search engines or else appear nearer to the top of such search outputs.

Store Image

Over the years, some researchers have challenged the basic utilitarian premise of location models by arguing that the attraction of a retail facility involves dimensions other than distance and mass. For instance, the drawing power of a retail site is also influenced by consumers’ image perceptions of the store or shopping area (Bucklin, 1967; Finn and Louviere, 1996). Consumers make judgments about and selections of stores based on subjective ratings on various image dimensions. Site location research is further extended when store image is incorporated as a component of attraction to shopping areas (Gentry and Burns, 1977; Nevin and Houston, 1980). Academic research on mall shopping has revealed that many consumers are prone to make a decision as to where to shop based on their attitude toward shopping center environment (Finn and Louviere, 1990, 1996; Gentry and Burns, 1977). In their study of bricks-and-mortar stores, Berman and Evans (1995) divide atmospheric stimuli into four categories: the exterior of the store, the general interior, the layout and design variables, and the point-of-purchase and decoration variables. As in physical shopping, buyers may prefer to consummate and repeat shopping experiences in an e-store that induces pleasant and rewarding feelings (Lynch, Kent, and Srinivasan, 2001). Here, Web-based retail environmental variables include the layout and design of an e-store Web site, ease of use, the download speed, and the ease of navigation within the e-store. We propose that:

P11: Consumers’ image perception of an online store affects their purchase behavior. Specifically, a favorable image perception is associated with an increased likelihood of online patronage.

Service Quality

In a traditional retail setting, service is always counted as an important factor contributing positively to the shoppers’ overall experience (e.g., Klassen and Glynn, 1992; Solomon et al., 1985). When shoppers interact with a faceless, non-personal entity as in the case of a virtual store, service quality seems particularly important. Needless to say, service offered in an online store takes a slightly different form. Online shoppers very often draw clues about service quality based on intangible attributes such as store operations policy. For instance, lenient return policy, provision of 24/7 1-800 service hotline, among others, are market cues for online service quality. Note that many online services are enabled by technological advances. For instance, software agents installed at a store Web site may allow consumers to more efficiently screen the set of alternatives available in an online shopping environment.

P12: Good service is associated with an increased likelihood of online patronage.

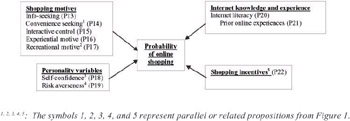

Competing Model Developed from E Commerce Literature

In this section, a competing model is forged on the basis of our learning from the emerging EC literature (see Figure 3-2). Potential predictor variables are drawn based on our review of studies published in the EC field, many of which specifically deal with online shoppers and e-tailing. Four factors (i.e., shopping motives, personality variable, Internet knowledge and experience, shopping incentives) are identified as the key determinants of online patronage. The propositions that are represented in the model are described in more detail in the rest of the chapter. As in the first model, this competing model also assumes that consumers have access to the Internet and have prior online experiences. Note that some variables appear in both baseline and competing models (e.g., self-confidence, recreational motive, convenience seeking), and these overlaps are indicated in the figures. This is not uncommon, since the Internet is simply another retail outlet that consumers can choose from their consideration set of possible places to go shopping. Not surprisingly, e-tailing bears a lot of resemblances to its counterpart in an off-line setting. What is more interesting is how our knowledge about traditional retailing can contribute to our study of e-tailing. In this following section, we propose a second model (based on EC research). We attempt to identify the similarities shared by the two models (derived from largely independent) research streams and also identify key differences or contrasts.

Figure 3-2: Proposed model of online patronage (given that consumers have Internet access and experiences)

Online Shopping Motivations

Information Seeking

The Internet provides an archive of product and company information. If the Web is good at anything, it is good at presenting tons of information and involving people in the process of sorting through it (Schwartz, 1997). The Web also organizes information for consumers. It learns about consumers’ preferences, based on past visits and reorganizes the information content and the way it is presented. For instance, Amazon.com groups customers based on their previous purchases, and then tailors suggested books to a consumer’s preferences once he embarks on a new search. The information seeking orientation led to the earlier popularity of the Web and now starts to draw the online population to the virtual market. The online medium facilitates utilitarian behavior as search costs for product information are dramatically reduced (Wolfinbarger and Gilly, 2001). With a few clicks, online shoppers can find relevant information (e.g., competitive brands, best price offers, product specifications, consumer word-of-mouth) on a product of interest in a fast fashion. Furthermore, online buyers feel that they can more fully investigate options than they can offline. Price comparisons in an information-rich environment are fairly easy, and thus the potential for savings significant, the economic motivation to shop on the Web could be strong (Anders, 1998). Hence, we offer the following proposition:

P13: Shoppers’ information-seeking tendency increases the probability of online shopping.

Convenience Seeking

Goal-oriented or utilitarian shopping has been described as task-directed, efficient, rational, and deliberate. Thus, goal-focused shoppers are transaction-oriented and want to accomplish a deal quickly and without distraction. Online consumers tend to be goal-focused rather than experiential (Wolfinbarger and Gilly, 2001). One attribute that attracts goal-oriented shoppers to e-tailing is convenience. In a recent research report, Greenfield online finds that some Internet users prefer online shopping over in-store shopping because of its convenience and that the consumers who value convenience are more likely to buy over the Internet (Li, Kuo, and Russell, 1999). Li and his colleagues (1999) discover a noticeable pattern that consumers value shopping convenience more highly as their Web shopping frequency increases.

The Internet enables consumers to have the world at their fingertips. The Internet facilitates comparison shopping and speeds up the finding of item. The ease and convenience of shopping from home at any time of day or night is an appealing allurement for shoppers in virtual reality (Donthu and Garcia, 1999; Pastore, 2000). Many find it convenient, local and thrifty.

One of the key aspects of human life in the 21st century is the paucity of time (Watson et al., 2000). Marketers who find ways to save time for consumers (e.g., through the successful application of the Internet) have the potential for great success and a chance to attract loyal customers. The Web comes in handy since this medium allows people to shop at stores not available in their geographic area (Edenkamp and Czark, 2000). This would suggest that online shopping may save fuel costs and travel risks. Geographic restricted areas where the distance of conventional retail stores can reach over eighty miles one way, benefit from the virtues of online shopping. In addition, the availability of “24-hour shopping” is a bonus. Consumers can avoid hitting rush hour traffic and waiting in long checkout lines by simply clicking a few buttons on their home computer. Based on the above argument, we offer the following proposition:

P14: Consumers’ convenience seeking tendency enhances the probability of online shopping.

Interactive Control

The Internet, as a new medium, is two-sided, active and timely. It obviates the need for sales personnel. Many sales clerks are order takers at best and many actually offend shoppers with poor manners and service. Many online buyers revel in the fact that they can get the transaction done without having to go through a salesperson. The ability to find what they need and to complete a transaction without having to go through third party is associated by online buyers with increased freedom and control. The interactive element of the Web puts the users in charge of the medium (Korgaonkar and Wolin, 1999) as well as the transaction. The user can choose which Web site to view, when to view it, or even exchange product information in specialized chat rooms. The interactive feature of the Web allows consumers to personalize and customize their experience by choosing among its huge selection. Therefore, it is not surprising that heavy users of the Internet tend to have a strong internal locus of control (Wolfinbarger and Gilly, 2001). Online shoppers enjoy their increased sense of control in the cyberstore compared to other purchase situations. Therefore, we propose that:

P15: A desire for interactive control enhances the probability of online shopping.

Shopping Experience

Shopping can be a social and very often recreational experience for many. Purchasing via the Web may be convenient and time-efficient, but it can also be isolating, unsatisfying and boring. Moreover, online shopping cannot satisfy the desire for immediate gratification (Rosen and Howard, 2000). For large-ticket, non-standardized, highly differentiated items, consumers would like to physically inspect them prior to purchase. Empirical studies have ascertained these anticipations. One of the research findings of Greenfield Online is that consumers who prefer experiencing products are less likely to buy online (Li, Kuo, and Russell, 1999). At present, the Web has large capacity for demonstrating product information, including some search attributes of products such as sizes, colors, models and prices, even sound (e.g., consumers can check out digital products such as CD by downloading a trial version). Some online stores offer chat rooms, auctions, or other functions to enhance the shopping experience or facilitate communications among shoppers. Though it allows consumers to experience to some degree the pleasure of shopping, the Internet is still not as sufficient as the off-line storefronts to provide consumers the “hands-on” experience. For consumers who shop out of social or recreational motives, the virtual marketplace cannot compete with retail stores to meet their needs (Li, Kuo, and Russell, 1999). On the other hand, online buyers largely like the relative lack of social interaction while buying online (Wolfinbarger and Gilly, 2001). Simply put, the desire for human interaction, the social aspect of shopping, and the ability to pick up and sample products are impossible to replicate online. Hence:

P16: Experiential shoppers are less likely to be Internet shoppers.

P17: Recreational shoppers are less likely to be Internet shoppers.

Psychographics and Personality Traits

Self-Confidence

Most Internet shoppers evidence a rich, active, and diverse lifestyle (Chang and McFarland, 1999). Many travel, attend sporting events, participate in sports, and have health club memberships. Those who are more open to technological advances are able to exercise better control over emerging tech-related challenges, and hence likely to have more personal confidence (Pan and Crask, 2001). These people tend to dominate in online shopping as they are not easily turned away by the technology and risk involved. Hence, we have:

P18: The higher a consumer’s self-confidence, the more likely that consumer is to shop on the Internet.

Risk Averseness

Internet users have the innovator and risk-taker personality type (Donthu and Garcia, 1999). Fifty percent of the Internet population belong to the Actualizer segment (active, discriminating, and adventurous), and eighteen percent belong to the Experiencers segment (innovative, stimulation seekers, and fashionable) (SRI International, 1995). Internet shoppers are more willing to try new things and are less concerned with the risk involved with their purchases (Donthu and Garcia, 1999). The aversion of risk among online shoppers is below average. We propose that:

P19: Risk averse consumers are less likely to shop on the Internet than risk takers.

Internet Knowledge and Experience

Internet Literacy

The Internet can perform multiple functions as a communication, transaction, and/or distribution channel. For consumers, shopping via the Web can be a slow, frustrating venture, especially for those unfamiliar with navigation through it. Actual use of the Internet as a shopping channel requires knowledge about the Web or what is normally referred to as “Internet literacy.” We speculate that consumers with different levels of channel knowledge tend to feel differently about using the Web for shopping purposes. Channel knowledge is the strongest predictor in Li, Kuo, and Russell’s (1999) model of online buying behavior. The authors notice that knowledgeable consumers tend to perceive more positively of the online channel’s utilities, which, in turn, will have a positive impact on purchase behavior. Hence, we have:

P20: Consumers who consider themselves knowledgeable about the Internet, as a channel, are more likely to purchase online than those who do not.

Prior Online Experiences

A “customer life cycle” approach presumes that consumers are on a continuum of online experiences. They have different levels of knowledge and experiences about the Internet. A consumer’s prior online experiences (e.g., online purchase and subsequent consumption experiences, interactions with e-stores, information acquisition via the Web) play a crucial role in shaping his overall judgment of Web-based transactions. Consumers’ positive prior online experiences contribute to build their trust in conducting transactional exchanges through this new medium. In the case of positive prior online experiences, the probability of the consumer revisiting the previous Web site(s) or visiting a limited number of Web sites with which the consumer has no negative associations, increases (Maity, Zinkhan, and Kwak, 2002). Therefore, we propose that:

P21: Consumers’ positive prior online experiences increase the probability of online patronage.

Monetary Purchase Incentives

As in the physical world, e-tailers are developing sales promotions and purchase incentives. For example, ClickrewardsTM offers frequent flyer air miles when purchasing from certain online stores. Mypointsâ offers bonus points that can be redeemed for purchases online (Walsh and Godfrey, 2000). Cyberstores occasionally feature some advertised products at premium prices. These promotional activities may give shoppers an incentive to patronize the online store. In their empirical study on Internet retail store design, Lohse and Spiller (1999) find that promotion on the cybermall entrance screen generates traffic and sales. In a focus-group discussion, online shoppers mention that one big reason they browse is bargain hunting (Wolfinbarger and Gilly, 2001). Another motivator for shopping online is avoiding sales taxes. All these discussion lead to the following proposition:

P22: Purchase incentives offered on the Internet (e.g., no sales tax, sales promotions, bonuses, price discount) increase the probability of online patronage.

Summary of Predictors of Online Patronage

Combining both traditional and e-commerce research streams, we set forth a list of factors that seem to contain explanatory power for predicting online patronage. These factors are grouped as either buyer-related factors (i.e., shopping motives, consumer psychographics, Internet knowledge/experience) or seller-related factors (i.e., e-tailer characteristics).

- Shopping motives: info-seeking; convenience seeking; interactive control; experiential motive; recreational motive; affiliation motive; deal seeking

- Consumer psychographics: self-confidence; risk averseness; consumer innovativeness; attitude toward local shopping conditions

- Internet knowledge/experience: Internet literary; prior online experiences

- E-tailer characteristics: shopping incentives (e.g., low price offers, free delivery); accessibility; wide selection of products; store image/atmosphere; service quality

Interactions

Note that there might be interactions among some predictor variables, though they are not highlighted in the proposed models. For instance, we have sound reasons to believe that a connection can be established between prior online experiences and Internet literacy. When people’s online experiences increase, their knowledge about the Internet as a channel, and the channel’s utilities, will also increase naturally. In addition, possible interactions in the two models (Figures 3-1 and 3-2) include:

- Interaction between store image and product selection. Stewart and Hood (1983) found that consumers had distinct images of each store, and these images could serve as the basis for segmenting store customers. For instance, shoppers at the low-priced stores were primarily concerned with convenience, price, and product selection.

- Interaction between experiential and recreational shopping. The recreational side of shopping experiences may in itself include the physical inspection of products, or the “hands-on” experiences. There might be no clear distinction between shoppers’ experiential and recreational motivation.

- Interaction between convenience seeking and accessibility. The attraction of a retail facility in terms of location may be more pronounced in the eyes of a convenience seeker.

Implications and Directions for Future Research

Our study aims to provide a broad view of Web-based shopping, incorporating a wide variety of predictors and approaching the topic from different perspectives. We propose two competing models of online patronage behavior derived from different research streams in marketing research. There are some similarities between the two models. For instance, there are some important overlaps, with four predictor variables (i.e., self-confidence, convenience seeking, recreational motive, risk averseness) appearing in both models. A fifth related variable emerges with different focus in the two models. In the baseline model (based on traditional retailing literature), the variable “deal seeking” is categorized under “shopping motive” and is conceptualized from the shopper’s perspective. In the competing model (based on EC literature), the variable is portrayed from a seller’s perspective, under the label of “shopping incentive” (provided by etailers). Another similarity is that consumer-specific attributes play key roles in both models. Most predictor variables are germane to consumers themselves (e.g., their shopping motives, their personality/psychographics, their level of Internet literacy, their prior online experiences).

Nonetheless, the two proposed models do include very different predictors for online patronage. The baseline model includes a number of store-relevant predictors (such as attraction of the retail facility). These variables (accessibility, product selection, store image) are noticeably missing in the EC-based model, suggesting one gap yet to be bridged in the extant EC literature. Recently, EC researchers embarked on a series of rigorous studies on the extent to which a Web site facilitates efficient and effective shopping and purchasing. Among these research efforts are the development of scales for evaluating service quality delivery through Web sites (Zeithaml, Parasuraman, and Malhotra, 2001), and the focus on the usability (including navigation, ease of use, search functions, overall site design) (Lohse and Spiller, 1998, 1999), playfulness (Liu and Arnett, 2000), and entertainment (Eighmey and McCord, 1998) of shopping Web sites. However, to some extent, the EC literature is developing in isolation from the retailing literature. For instance, even though the EC literature deals with such issues as Web site quality or attractiveness, no explicit parallel is drawn to the atmospherics concept from the retailing literature. In this study, we propose that some concepts under study for decades in traditional retailing (e.g., product selection, store image, attitude toward local shopping conditions) still contain explanatory power for researching electronic retailing. Features from bricks-and-mortar retail stores relate to online retail stores. Needless to say, the “Clicks” and “Bricks” do not bear exact resemblance. However, there are some analogies between bricks-and-mortar stores and online retail stores. For instance, the etailing analogy for “store atmosphere” is “interface consistency, store organization, interface and graphics quality” and that for “store size” is “wide selection of products, monthly store traffic, number of offices in major cities, number of employees.”

The Internet is evolving rapidly. For instance, a few years ago, when e-tailing was still a relatively new mode of selling, online shoppers tended to be male, well educated, and socio-economically upscale. Now, the Internet appears to be going more mainstream in its demographic makeup, and this trend is likely to continue. This ever-changing nature of the Internet presents some challenges to e-commerce researchers. Any work on Internet-related issues seems to be an effortful attempt to capture a moving target. Therefore, caution should be exercised when interpreting the models proposed in the current study. Some explanatory variables (e.g., risk-averseness, consumer innovativeness) are time dependent. Readers can reasonably suspect that we are not far off the situation where these propositions are no longer true for the generic online behavior. Innovators, for instance, will be moving on to newer generations of options and services enabled by technological advances.

One limitation of this study results from the width of the predictors. It is difficult, if not impossible, to test the entire conceptual models in one empirical study. This is very often a born problem for many holistic typologies. Nonetheless, the two proposed models can lead to a plethora of research opportunities. Future empirical research may be designed to test a component of the models.

- Theoretical contributions. Here, we propose two conceptual models (see Figures 3-1 and 3-2) and a variety of propositions to explain patronage behavior on the Web. The proposed models are derived from disparate research streams. One of our main contributions is making a connection between offline retailing theory and online retailing practices. In addition, we try to gauge the current level of knowledge about e-tailing. We adapt this knowledge and integrate it into two competing models, derived from different research streams. By contrasting these two models, we identify the link missing in the current e-commerce research on online patronage. We argue that EC research on online shopping should be built upon and developed in conjunction with our time-honored learning and practices in the bricks-and-mortar retailing. EC research will have the momentum and resources to mature into a full-fledged subject if it benefits from the reservoir of previous research findings in the traditional retailing literature. Further research can be devoted to designing empirical studies to test our conceptual models. Actual purchase data from online shoppers should be collected to test the models and their corresponding hypotheses. We don’t explicitly explore interaction effects in this chapter. Future researchers may want to explore interactions and their consequences.

- Managerial implications. It is generally agreed that e-tailing is a good supplement to, but not a complete replacement for, bricks-and-mortar retailing. E-tailing (often in partnership with on-ground stores) is expected to expand in economic importance, so research in this area is much needed in order to understand hybrid business models (e.g., part on-ground strategy part online strategy). Despite rapid advances in Internet shopping, much is yet to be learned about consumers’ patronage behavior. The Internet can function as a communication channel as well as a retailing outlet. By focusing on the buying and selling aspect of the new medium, the current study investigates issues that are of great interest to retailing managers. We suggest a profile of online shoppers. For instance, Internet shoppers tend to be deal-prone and concerned with time management. E-tailers need to design their cyber storefronts so as to appeal to these shopper characteristics, making it easy for consumers to search for and locate the company and/or its offerings (e.g., products, services, information).

Conclusion

This conceptual study explores various antecedents of online purchase behavior, including shopping motives, consumer psychographics, Internet literacy, prior online experiences, and attraction of the retail facility. Future research can compare online shoppers versus in-store shoppers on these dimensions. Such knowledge, if available, would contribute to the heated debate on whether e-tailing is a unique mode of retailing, or, in contrast, an extension of traditional retailing. Interested researchers can also work on identifying sources of customer satisfaction and dissatisfaction as well as exploring the interrelationship between online and off-line shopping experiences. It may be that we need to develop new retailing theories to account for phenomena that are emerging in cyberspace.

References

Anders, G. (1998, November 4). Some big companies long to embrace Web but settle for flirtation. Wall Street Journal.

Ashley, B. (1997). Are malls in America’s future? Arthur Anderson Retailing Issues Letter, 9(6).

Bauer, R. A. (1960). Consumer behavior as risk taking. Dynamic marketing for a changing world. Chicago: American Marketing Association.

Bearden, W. O., & Mason, J. B. (1979). Elderly use of in-store information sources and dimensions of product satisfaction/dissatisfaction. Journal of Retailing, 55(1), 79-91.

Bellenger, D. N., & Korgaonkar, P. K. (1980). Profiling the recreational shopper. Journal of Retailing, 56(3), 77-91.

Bellenger, D. N., Robertson, D. H., & Greenberg, B. A. (1977). Shopping center patronage motives. Journal of Retailing, 53(2), 29-38.

Berkowitz, E. N., Walton, J. R., & Walker, O. C. (1979). In-home shoppers: The market of innovative distribution systems. Journal of Retailing, 55(2), 15-33.

Berman, B., & Evans, J. R. (1995). Retail management: A strategic approach. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bettman, J. R. (1973). Perceived risk and its components: A model and empirical test. Journal of Marketing Research, 10(2), 184-190.

Bettman, J. R. (1975). Information integration in consumer risk perception: A comparison of two models of component conceptualization. Journal of Applied Psychology, 60(3), 381-385.

Blattberg, R., Buesing, T., & Peacock, P. (1978). Identifying the deal prone segment. Journal of Marketing Research, 15(3), 369.

Bloch, P. H., Ridgway, N. M., & Dawson, S. A. (1994). The shopping mall as consumer habitat. Journal of Retailing, 70(1), 23-42.

Boone, L. E. (1974). Personality and innovative buying behavior. Journal of Psychology, 86, 197-202.

Botwinick, J. (1973). Aging and behavior. New York: Springer Publishing Company.

Bucklin, L. P. (1967, October). The concept of mass in intra-urban shopping. Journal of Marketing, 31, 37-42.

Chang, Y., & McFarland, D. (1999). Scarborough research study of the lifestyle of e-shoppers and the ‘wired but wary’. Retrieved from: http://www.scarborough.com/scarb2000/press/pr_eshoppers.htm

Childers, T. L., Carr, C. L., Peck, J., & Carson, S. (2001). Hedonic and utilitarian motivations for online retail shopping behavior. Journal of Retailing, 77, 511-535.

Cockerham, P. W. (1995). Homart revives Virginia Mall with renovation and remarketing. Stores, 16-18.

Cox, D. F., & Rich, S. U. (1964, November). Perceived risk and consumer decision-making — The case of telephone shopping. Journal of Marketing Research, 1, 32-39.

Craig, S., Ghosh, A., & McLafferty, S. (1984). Models of retail location process: A review. Journal of Retailing, 60(1), 5-36.

Cunningham, I. C., & Cunningham, W. H. (1973). The urban in-home shopper: Socioeconomic and attitudinal characteristics. Journal of Retailing, 49(4), 42-50, 88.

Darden, W. R., Lennon, J. J., & Darden, D. K. (1978). Communicating with interurban shoppers. Journal of Retailing, 54(1), 51-64.

Darden, W. R., & Perrault, W. D. (1976, February). Identifying interurban shoppers: Multiproduct purchase patterns and segmentation profiles. Journal of Marketing Research, 13, 51-60.

Darian, J. C. (1987). In-home shopping: Are there consumer segments? Journal of Retailing, 63(3), 163-186.

Degeratu, A. M., Rangaswamy, A., & Wu, J. (2000). Consumer choice behavior in online and traditional supermarkets: The effects of brand name, price, and other search attributes. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 17, 55-78.

Dhar, S. K., Hoch, S. J., & Kumar, N. (2001). Effective category management depends on the role of the category. Journal of Retailing, 77(2), 165-184.

Donovan, R. J., & Rossiter, J. R. (1982). Store atmosphere: An environmental psychology approach. Journal of Retailing, 58(1), 35-56.

Donovan, R. J., Rossiter, J. R., Marcoolyn, G., & Nesdale, A. (1994). Store atmosphere and purchasing behavior. Journal of Retailing, 70(3), 283-294.

Donthu, N., & Garcia, A. (1999). The Internet shopper. Journal of Advertising Research, 39(3), 52-58.

Edenkamp, B., & Czark, G. (2000). Buy buy baby boomer. Brandweek, 41(26), 18.

Eighmey, J., & McCord, L. (1998). Adding value in the Information Age: Uses and gratifications of sites on the World Wide Web. Journal of Business Research, 41(3), 187-194.

Farmer, C. (1988, January/February). The fading of the American dream. Retail and Distribution Management, 16, 23-25.

Finn, A., & Louviere, J. (1990). Shopping center patronage models: Fashioning a consideration set segmentation solution. Journal of Business Research, 21(3), 159-175.

Finn, A., & Louviere, J. (1996, March). Shopping center image, consideration, and choice: Anchor store contribution. Journal of Business Research, 35, 241-251.

Forman, A. M., & Sriram, V. (1991). The depersonalization of retailing: Its impact on the ‘lonely’ consumer. Journal of Retailing, 67(2), 226-243.

Forsythe, S. M., & Shi, B. (2003). Consumer patronage and risk perceptions in Internet shopping. Journal of Business Research, 56(11), 867-875.

Gentry, J. W., & Burns, A. C. (1977). How ‘important’ are evaluative criteria in shopping center patronage? Journal of Retailing, 53(4), 73-86, 94.

Ghosh, A. (1986). The value of a mall and other insights from a revised central place model. Journal of Retailing, 62(1), 79-97.

Gillett, P. L. (1970, July). A profile of urban in-home shoppers. Journal of Marketing, 34, 40-45.

Gillett, P. L. (1976). In-home shoppers: An overview. Journal of Marketing, 40(4), 81-

88.

Goldsmith, R. (2002). Explaining and predicting consumer intention to purchase over the Internet: An exploratory study. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 10(2), 22-28.

Graham, E. (1988). The call of the mall. The Wall Street Journal, 7R.

Graham, R. J. (1981, March). The role of perception of time in consumer research. Journal of Consumer Research, 7, 335-342.

Haubl, G., & Trifts, V. (2000). Consumer decision making in online shopping environments: The effects of interactive decision aids. Marketing Science, 19(1), 4-21.

Havlena, W. J., & Holbrook, M. B. (1986, December). The varieties of consumption experience: Comparing two typologies of emotion in consumer behavior. Journal of Consumer Research, 13, 394-404.

Hirschman, E. C. (1984). Experience seeking: A subjectivistic perception of consumption. Journal of Business Research, 12(1), 115-136.

Hirschman, E. C., & Holbrook, M. B. (1982, Summer). Hedonic consumption: Emerging concepts, methods and propositions. Journal of Marketing, 46, 92-101.

Huff, D. L. (1962). Determination of intra-urban retail trade areas. In Real Estate Research Programs (pp. 11-12). Los Angeles: The University of California.

International, S. (1995). Exploring the World Wide Web population’s other half. Retrieved from http://www.future.sri.com

Jacoby, J. L., Kaplan, B., & Szybillo, G. J. (1974). Components of perceived risk in product purchase. Journal of Applied Psychology, 59(287-91).

Jarvenpaa, S., Tractinsky, N., Saarinen, L., & Vitale, M. (1999). Consumer trust in an Internet store: A cross-cultural validation. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 5(2).

Kassarjian, H. H. (1971). Personality and consumer behavior: A review. Journal of Marketing Research, 8, 409-418.

Kerschner, P. A., & Chelsvig, K. A. (1981, October 22-23). The aged user and technology. Paper presented at the Conference on Communications Technology and the Elderly: Issues and Forecasts, Cleveland, Ohio.

King, C. W. (1965). Communicating with the innovator in the fashion adoption process. Paper presented at the American Marketing Association Conference.

Klassen, M. L., & Glynn, K. A. (1992). Catalog loyalty: Variables that discriminate between repeat and non-repeat customers. Journal of Direct Marketing, 6(3), 60-67.

Korgaonkar, P. K. (1982). Consumer preferences for catalog showrooms and discount stores: The moderating role of product risk. Journal of Retailing, 58(4), 76-88.

Korgaonkar, P. K., & Wolin, L. D. (1999). A multivariate analysis of Web usage. Journal of Advertising Research, 39(2), 53-68.

Levy, M., & Grewal, D. (2001). Passing the baton. Journal of Retailing, 77, 429-434.

Levy, S. J. (2001). The psychology of an online shopping pioneer. Advances in Consumer Research, 28, 222-226.

Li, H., C. Kuo, & Russell, M. G. (1999). The impact of perceived channel utilities, shopping orientations, and demographics on the consumer’s online buying behavior. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communications, 5(2).

Liao, Z., & Cheung, M. T. (2001). Internet-based e-shopping and consumer attitudes: An empirical study. Information & Management, 38, 299-306.

Lichtenstein, D. R., Netemeyer, R. G., & Burton, S. (1990). Distinguishing coupon proneness from value consciousness: An acquisition-transaction utility theory perspective. Journal of Marketing, 54(3), 54-67.

Lin, C. A. (1999). Online-service adoption likelihood. Journal of Advertising Research, 39(2), 79-89.

Liu, C., & Arnett, K. P. (2000). Exploring the factors associated with Web sites success in the context of electronic commerce. Information & Management, 38(1), 23-34.

Lohse, G. L., Bellman, S., & Johnson, E. J. (2000). Consumer buying behavior on the Internet: Findings from panel data. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 14(1), 15-29.

Lohse, G. L., & Spiller, P. (1998). Electronic shopping. Communications of the ACM, 41(7), 81-87.

Lohse, G. L., & Spiller, P. (1999). Internet retail store design: How the user interface influences traffic and sales. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communications, 5(2).

Louviere, J. J., & Gaeth, G. J. (1987). Decomposing the determinants of retail facility choice using the method of hierarchical information integration: A supermarket illustration. Journal of Retailing, 63(1), 25-48.

Lumpkin, J. R., & Hawes, J. M. (1985). Retailing without stores: An examination of catalog shoppers. Journal of Business Research, 13, 139-151.

Lynch, P., Kent, R., & Srinivasan, S. (2001). The global Internet shopper: Evidence from shopping tasks in twelve countries. Journal of Advertising Research, 41(3), 15-23.

Maity, M., Zinkhan, G. M., & Kwak, H. (2002). Consumer information search and decision making on the Internet: A conceptual model. Paper presented at the Marketing Theory and Applications, Chicago, IL.

Mathwick, C. (2002). Understanding the online consumer: A typology of online relational norms and behavior. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 16(1), 40-55.

Mathwick, C., Malhotra, N., & Rigdon, E. (2001). Experiential value: Conceptualization, measurement and application in the catalog and Internet shopping environment. Journal of Retailing, 77, 39-56.

McClelland, D. C. (1987). Human motivation. New York: Cambridge University Press.

McDonald, W. J. (1993, Summer). The roles of demographics, purchase histories, and shopper decision-making styles in predicting consumer catalog loyalty. Journal of Direct Marketing, 7, 55-65.

Menon, S., & Kahn, B. (2002). Cross-category effects of induced arousal and pleasure on the Internet shopping experience. Journal of Retailing, 78(1), 31-40.

Miyazaki, A., & Fernandez, A. (2001). Consumer perceptions of privacy and security risks for online shopping. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 35(1), 27-44.

Muldoon, K. (1984). Catalog marketing. New York: R. R. Bowker.

Nevin, J. R., & Houston, M. J. (1983). Image as a component of attraction to intraurban shopping areas. Patronage behavior and retail management. New York: North Holland.

Pan, Y., & Crask, M. (2001). A comparative study of online shoppers and store-prone shoppers. Paper presented at the Developments in Marketing Science, San Diego, CA.

Papadopoulos, N. G. (1980). Consumer outshopping research: Review and extension. Journal of Retailing, 56(4), 41-58.

Pastore, M. (2000). Banner ads luring shoppers. Retrieved from http://adres.internet.com/ feature/article

Pearson, P. H. (1970). Relationships between global and specified measures of novelty seeking. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 34, 199-204.

Peet, J. (2000, February 26). Shopping around the Web. The Economist.

Peter, J. P., & Ryan, M. J. (1976, May). An investigation of perceived risk at the brand level. Journal of Marketing Research, 13, 184-188.

Peter, J. P., & Tarpey, L. X. (1975). A comparative analysis of three consumer decision strategies. Journal of Consumer Research, 2, 29-37.

Reynolds, F. D. (1974, July). An analysis of catalog buying behavior. Journal of Marketing, 38, 47-51.

Robertson, T. S. (1971). Innovative behavior and communication. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Rosen, K. T., & Howard, A. L. (2000). E-retail: Gold rush or fool’s gold? California Management Review, 42(3), 72-100.

Rubenstein, C., & Shaver, P. (1980). Loneliness in two northeastern cities. In The anatomy of loneliness. New York: International Universities Press.

Salste, T. (1996). The Internet as mode of non-store shopping. Unpublished manuscript.

Samli, A. C., & Uhr, E. B. (1974). The outshopping spectrum: Key for analyzing intermarket leakages. Journal of Retailing, 50(2), 70-78.

Schwartz, E. I. (1997). Webnomics. New York: Broadway Books.

Scott, A. (2001). Online shopping on the rise. The Internal Auditor, 58(1), 15-16.

Shim, S., Eastlick, M. A., Lotz, S. L., & Warrington, P. (2001). An online prepurchase intentions model: The role of intention to search. Journal of Retailing, 77, 397-416.

Solomon, M., Surprenant, C., Czepiel, J., & Gutman, E. (1985). A role theory perspective on dyadic interactions: The service encounter. Journal of Marketing, 49(1), 99-111.

Sproles, G. B., & Kendall, E. L. (1986, Winter). A methodology for profiling consumers’ decision making styles. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 20, 267-279.

Stewart, D., & Hood, N. (1983). An empirical examination of customer store image components in three UK retail groups. European Journal of Marketing, 17(4), 50-62.

Stoltman, J. J., Gentry, J. W., & Anglin, K. A. (1991). Shopping choices: The case of mall choice. Advances in Consumer Research, 18.

Swaminathan, V., E., Lepkowska-White, & Rao, B. (1999). Browsers or buyers in cyberspace? An investigation of factors influencing electronic exchange. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 5(2).

Szymanski, D. M., & Hise, R. T. (2000). E-satisfaction: An initial examination. Journal of Retailing, 76(3), 309-322.

Tang, F., & Xing, X. (2001). Will the growth of multi-channel retailing diminish the pricing efficiency of the Web? Journal of Retailing, 77, 319-333.

Tauber, E. M. (1972, October). Why do people shop? Journal of Marketing, 36, 46-49.

Udell, J. G. (1964-1965). A new approach to consumer motivation. Journal of Retailing, 40(4), 6-10.

Venkatraman, M. P. (1991). The impact of innovativeness and innovation type on adoption. Journal of Retailing, 67(1), 51-67.

Venkatraman, M. P., & Price, L. P. (1990). Differentiating between cognitive and sensory innovativeness: Concepts, measurement and their implications. Journal of Business Research, 20, 293-315.

Walsh, J., & Godfrey, S. (2000). The Internet: A new era in customer service. European Management Journal, 18(1), 85-92.

Watson, R. T., Berthon, P., Pitt, L. F., & Zinkhan, G. M. (2000). Electronic commerce: The strategic perspective. Fort Worth: The Dryden Press.

Weisbrod, G. E., Parcells, R. J., & Kern, C. (1984). A disaggregate model for predicting shopping area market attraction. Journal of Retailing, 60(1), 65-83.

Westbrook, R. A., & Black, W. C. (1985). A motivation-based shopper typology. Journal of Retailing, 61(1), 78-103.

Wolfinbarger, M., & Gilly, M. C. (2001). Shopping online for freedom, control, and fun. California Management Review, 43(2), 34-55.

Zeithaml, V. A., Parasuraman, P., & Malhotra, A. (2001). E-service quality: Definition, dimensions and conceptual model. Cambridge, MA.

Section I - Consumer Behavior in Web-Based Commerce

- Chapter I e-Search: A Conceptual Framework of Online Consumer Behavior

- Chapter II Information Search on the Internet: A Causal Model

- Chapter III Two Models of Online Patronage: Why Do Consumers Shop on the Internet?

- Chapter IV How Consumers Think About Interactive Aspects of Web Advertising

- Chapter V Consumer Complaint Behavior in the Online Environment

Section II - Web Site Usability and Interface Design

- Chapter VI Web Site Quality and Usability in E-Commerce

- Chapter VII Objective and Perceived Complexity and Their Impacts on Internet Communication

- Chapter VIII Personalization Systems and Their Deployment as Web Site Interface Design Decisions

- Chapter IX Extrinsic Plus Intrinsic Human Factors Influencing the Web Usage

Section III - Systems Design for Electronic Commerce

- Chapter X Converting Browsers to Buyers: Key Considerations in Designing Business-to-Consumer Web Sites

- Chapter XI User Satisfaction with Web Portals: An Empirical Study

- Chapter XII Web Design and E-Commerce

- Chapter XIII Shopping Agent Web Sites: A Comparative Shopping Environment

- Chapter XIV Product Catalog and Shopping Cart Effective Design

Section IV - Customer Trust and Loyalty Online

- Chapter XV Customer Trust in Online Commerce

- Chapter XVI Turning Web Surfers into Loyal Customers: Cognitive Lock-In Through Interface Design and Web Site Usability

- Chapter XVII Internet Markets and E-Loyalty

Section V - Social and Legal Influences on Web Marketing and Online Consumers

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 180

- Using SQL Data Manipulation Language (DML) to Insert and Manipulate Data Within SQL Tables

- Understanding SQL Transactions and Transaction Logs

- Writing External Applications to Query and Manipulate Database Data

- Retrieving and Manipulating Data Through Cursors

- Exploiting MS-SQL Server Built-in Stored Procedures