Characters and Story

The first step in creating animation is deciding what it will be aboutin other words, the story. You will also need to decide what characters will be involved in this story. Do you develop the story or the characters first?

You may already have a story you want to tell. In that case, you'll need to develop the characters to tell the story. On the other hand, you may have a library of characters you have modeled and want to use. In this case, you'll need to develop a story for the characters you're familiar with. Television series, for example, are written this way; the characters remain relatively constant and the stories are tailored to them.

Wherever you decide to start, you will soon realize that story and character are very tightly coupled. The story you choose will help define the characters through their actions. Strong characters will, in turn, affect the story. Sir Lawrence Olivier as Hamlet plays much differently than Mel Gibson in the same role. Imagining a character such as Bugs Bunny in that role brings forth even more hilarious differences.

The character determines how the role will play. Should you cast this character as a hero or villain?

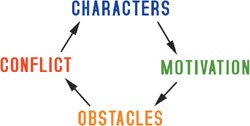

For a character to come to life, it will need motivation to make it want to do something and obstacles to make that task more interesting by causing conflict. These ingredients also make a good story.

Motivation Creates Character

In order for a character to do anything within a story, the character must be motivated. Characters are motivated by their needs: A little tramp is hungry and needs food. A powerful newspaper magnate needs money and power. Laurel and Hardy need to deliver a piano. What a character wants and needs determines who he or she is to the audience.

The way characters pursue their needs gives the audience clues to their personalities. Perhaps two characters are running for the same political office. One pursues it honestly; the other one uses every trick in the book. They both need the same thingpolitical officebut their personalities cause them to go about it differently. Another good example might be the simple task of jumping over a puddle. Fred Astaire would do it gracefully, while Buster Keaton might trip and land flat on his face.

Obstacles Create Conflict

If you can identify what your characters need, you can also create obstacles for them to overcome. This is what adds interest to the story. If Laurel and Hardy deliver the piano without incident, the story falls flat. Place a very steep staircase in their way, and they have an obstacle to overcome. The comedy is derived from the many ways the piano can slip from their hands and fall down the stairs. Overcoming the obstacle of the stairs is what creates the comedy. Obstacles can be physical, such as a staircase, but they can also take other forms. A character may need to overcome fear, for example. In any case, obstacles are the things that create conflict in a story.

This character is hungry, and the desire for food is a motivation.

This character is late for a wedding. The obstacles create conflict.

Conflict Creates Drama

Stories are about conflict. A character simply walking down the street is not a story. It is also not very interesting. The character needs motivationperhaps he is late and desperately needs to get to his wedding. If the street is littered with banana peels, you have an obstacle, which creates conflict and the beginnings of a story. Does the character avoid the peels? Does the character slip? If so, when? Does he make it to the wedding, and in what shape? It is up to the storyteller to make the most of the situation.

Of course, larger conflicts can generate much more intricate and substantial stories. Complexity adds spice to a story. Still, you need to be sure your story line is clear and not overly burdened by excessive complexity. There should typically be one main motivation and conflict in the story, with a limited number of secondary conflicts to add interest.

For example, consider a simple story: A bumbling scientist creates a monster that escapes the lab and terrorizes the city. Unfortunately, he can't bear to kill his creation. This simple story has several conflicts. The main conflict is the scientist trying to overcome the love he feels for his creation, but secondary conflicts are many: finding a way to destroy the monster, not getting killed by the monster, and so on.

Another example might be a wrongfully accused man who escapes from prison and must avoid the police while trying to clear his name. The conflict of keeping away from the cops is obvious, but the man's true motivation is proving his innocence. This is what drives the story. The cops and the chase simply add more obstacles and conflict to keep the story interesting.

The way a character handles conflict tells the audience something about his personality. If the mad scientist can't kill his creation, it's because he has feelings of love for the creature. This, in turn, will evoke empathy from the audience.

Conflict can also be much subtler. Many stories deal with internal conflicts, such as a character struggling with personal demons, growing up, or changing in some way. Internal conflict, however, will most likely manifest itself externally. An insecure character, for example, may act subordinate to a domineering spouse. The conflict is resolved only when the character confronts the insecurity and stands up to the spouse. In this case, the spouse represents the inner conflict. The events leading up to the confrontation are what tell the story.

Stories are a circular thing. Characters are driven by motivations, and blocking the way are obstacles, which cause conflict, which further defines the characters.

Just as in war, when a conflict ends, there is resolution. This is the "payoff" of the story. In the case of the fugitive, the real perpetrator is caught and our hero goes free. Or he doesn't. Too often, resolutions take the form of "and they lived happily ever after." This might be nice for a children's story, but resolutions work best when the ending has a slight twistone last surprise for the audience.

Visual Storytelling

When writing a novel, an author can delve into the mind of a character to tell you what he or she is thinking. A line such as "Mary was happy with herself" could very easily be written into a novel with no problems at all. In a script, however, these sorts of statements can cause tremendous problems. We can't just say Mary is happy, we have to show ithow else will the audience know what she is feeling? They're not reading a script, they're watching a film. Mary will need to demonstrate her change of emotion through an action that the audience can see.

How she demonstrates this emotion will also give the audience clues to her character. If she is a shy person, perhaps she will simply smile. A more gregarious Mary might jump for joy. Perhaps the moment could include dialogue in addition to the action. However, her actions are what define Mary to the audience.

If this character says "I'm so happy," the audience will think he is happy.

Film and animation are primarily visual media, and studies have shown that visuals are more important than audio: if the audio contradicts the image, the image will win. Politicians have been known to use this fact with great results. If a politician is seen on the news in a visually appealing or patriotic setting, viewers will think more positively about the politician, even if the news reporter's audio narration says negative things.

This is not to say that dialogue and audio are unimportant. Sound effects are very important. What a character says is extremely important. What the character does, however, is always most important. The image defines the sound, not the other way around. A line of dialogue like "I'm so happy" will read straight if the character is smiling and acting happy. If the character acts sad as he says this, the image will win, and the audience will interpret the character as sad, ironic, or both. When writing a script for animation, you must take the visuals into account at all points.

If this character says "I'm so happy," the meaning is unclear and the visual wins over the dialogue.

Chapter One. Basics of Character Design

- Chapter One. Basics of Character Design

- Approaching Design as an Artist

- Design Styles

- Designing a Character

- Finalizing Your Design

Chapter Two. Modeling Characters

Chapter Three. Rigging Characters

- Chapter Three. Rigging Characters

- Hierarchies and Character Animation

- Facial Rigging

- Mesh Deformation

- Refining Rigs

- Conclusion

Chapter Four. Basics of Animation

- Chapter Four. Basics of Animation

- Understanding Motion

- Animation Interfaces

- The Language of Movement

- Secondary Action

- Conclusion

Chapter Five. Creating Strong Poses

- Chapter Five. Creating Strong Poses

- Posing the Body Naturally

- Creating Appealing Poses

- Animating with Poses

- Conclusion

Chapter Six. Walking and Locomotion

- Chapter Six. Walking and Locomotion

- The Mechanics of Walking

- Animating Walks

- Beyond Walking

- Adding Personality to a Walk

- Transitions

- Conclusion

Chapter Seven. Facial and Dialogue Animation

Chapter Eight. Animal Motion

Chapter Nine. Acting

- Chapter Nine. Acting

- Acting Vs. Animating

- Acting and Story

- Acting Technique

- Acting and the Body

- Other Techniques

- Conclusion

Chapter Ten. Directing and Filmmaking

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 84