Developing a Story

The essence of story structure is simple. You'll start with a character who is motivated by a need. To meet that need, the character must overcome obstacles. As the character deals with the obstacles, the audience learns more about who the character is. The concept is simple to explain, but telling a story well is an art form. Now that you understand some of the basic elements of storytelling, you can start to develop stories of your own.

What type of story will you create? There are quite a few. There's the simple story with a full plot that has a beginning, middle, and end. There are also stories that are really just a collection of gags strung together, as in a Road Runner cartoon. Even those simple cartoons have the essential basics of a storythe Coyote's motivation is to catch the Road Runner. He just seems to encounter plenty of obstacles along the way.

Keep It Simple

While it is wonderful to imagine the most incredible and complex stories, there will always be limits. Even the biggest studio blockbuster has a fixed budget, and for a one-person production, the limit is the amount of time that you can give to the project. Most projects fall somewhere in the middle of these extremes.

With any project, there is always the tendency to bite off more than you can chew. Creating a story is easy. Actually producing it is another matter altogether. It is always best to keep your time and budget constraints in mind. Knowing how much time and effort will be required to produce a particular film is knowledge gained mostly from experiencethe more films you make, the more aware you will be of the time and expense involved.

If you are a student creating your first film, the best advice is to keep it small. This means sticking to a handful of characters and a situation that is manageable. Usually two to three minutes is plenty, and four to five minutes is ambitious. Films longer than five minutes might require some outside help. Remember, the classic Warner Brothers cartoons were all only six minutes long.

Simplicity is typically the best way to go. Most of the best short films have very simple plots and stories. The Pixar shorts are great examples: they each have only a handful of characters and one simple conflict. Another case for keeping the story simple and the number of characters small is that you can spend more screen time developing each character, and isn't "character" what character animation is all about?

Brainstorming a Premise

There are many ways to develop stories. One way is simply to brainstorm ideas. Brainstorming is an exercise in pure creativity. If you prefer to write out your thoughts, get a sheet of paper and start writing down ideas. If you like to work the story out visually, you can also make simple sketches.

Your story should have at least one character, one motivation, and one obstacle. It could be as simple as a child trying to open a childproof container. Or you could turn that idea on its head and have the adult be incapable of opening the container, while the child, the dog, and even the pet hamster have it all figured out. A character could be extremely hungry, but food is hard to get. You could base your story on a traditional fairy talemaybe the three little pigs who build houses out of straw, twigs, and bricks to avoid the wolf. If you want to add a twist to that concept, make them the three little lab rats who build mazes out of DNA to avoid the scientist. As you can see, the core idea of a film can be stated very simply in one or two lines. This simple statement is called a premise. Creating a good premise is your first step in creating a good film.

Developing Your Premise into a Story

As you can see, the possibilities for premises are limited only by your imagination. Once you have a premise in hand, you need to ask yourself some very serious and objective questions about how the film will be made.

The first question is whether the film can be made at all. If it's a story about fish, for instance, you may need to animate water. If your story is about a barber, you may need to animate realistic hair. Ask yourself if your software is capable of handling the types of shots and characters the premise demands. If not, you may want to choose another premise or put the premise into another setting.

You also need to think about length. Some stories cannot be told in a few minutes, though you'd be surprised at how much you can cram into that span of time. Many commercials tell great little stories in 30 to 60 seconds. Simple is usually better, however. Typically, this means focusing on one set of characters, one motivation, and one set of conflicts.

One way to flesh out your story is by going through another brainstorming session to generate as many ideas related to the story as possible. Write these ideas down on note cards, so you can keep track of them and arrange them into a story.

If your premise is good, you can generate plenty of ideasfar too many to fit within your time constraints. Should you have too much material, you can think of it as either a luxury or a curse: If deleting the extra material from your story makes it incomprehensible, your story might be cursed with too much complexity. You probably need to take a step backward to rethink the premise or the major story points to get the film to a manageable length. If you can toss out material and still have a sound story, then you have the luxury of too much good stuff. Keeping only the best material will make your film that much stronger. Even if you have lots of great material, don't delude yourself into thinking that it all needs to be put in the film. Every extra bit of material means an extra animation for you to complete. If you bite off more than you can chew, it can come back to haunt you later.

Developing a Script

Once you have a ton of ideas, you'll have a stack of note cards and will need to organize your story so that you know, beat for beat, the exact sequence of events, including the ending. Let's take the idea of the adult who can't open the childproof bottle. Getting to the contents of the bottle is the adult's motivation; the complex cap is the obstacle. Pretty simple story.

In fleshing the story out, you could have the adult use all sorts of wild schemes to get the cap off: a can opener, a blowtorch, dynamite. If other characters, like a kid, a dog, and a hamster, manage to open the bottle with no help, it can just serve to humiliate the adult and strengthen his motivation, as he sees that his goal is possible.

Organizing the story means that you need to build the gags, one at a time. A simple structure might be alternating the adult's attempts with those of the other characters. The adult tries opening the bottle by hand, gives up, and then the child comes in and opens it. This motivates the adult further, who resorts to more drastic measures. These fail, and then another character opens the bottle. The adult's battle with the bottle escalates further, and so on.

All of these conflicts need to build to an ending as well. The ending could be simple, with the adult driving himself crazy with frustration. It could be ironic: he finally opens the bottle, only to find it empty. It could be a bit more fantastic: he has such a pounding headache that his head explodes. Or you could make a surreal Twilight Zone ending, where the adult and his world are itself contained within another giant childproof bottle. Again, there are an infinite number of twists and possibilities to any story.

As you finalize the structure of your story, you will also need to be writing a script. This could be as simple as a point-by-point outline of the action or as extensive as a full script, with dialogue and screen direction. Scripts do not have to be written documents; some directors dispense with written scripts and go straight to storyboard so they can visualize their film as it is written.

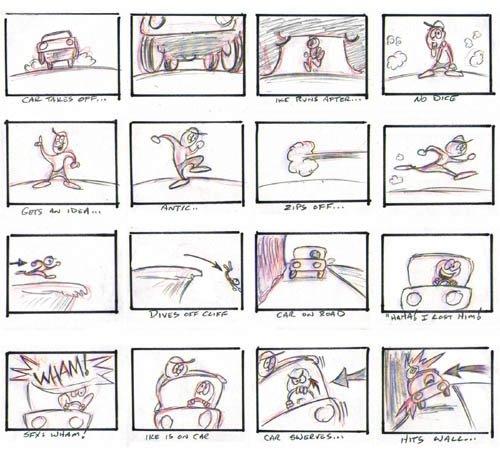

A good storyboard can replace a written script.

Adding Dialogue

As you write the script, you may also find it necessary to add dialogue. This is certainly not a requirement, as many of the best cartoons have no dialogue whatsoever. Dialogue does help considerably in defining your characters, however. A good script and voice performance will help your characters appear real and will make their personalities pop off the screen. A good voice track is also great for animators, who can use it to guide the performance.

If you decide to add dialogue to your film, you will need to hone your writing skills. Writing dialogue that sounds natural and unforced can be difficult. A couple of handy hints might make the process easier. First, listen to real conversations, perhaps even putting them on tape and transcribing them to see how they work. You'll notice that people tend to speak in short sentences or fragments, interrupting each other in many cases. Another way to get a sense of dialogue is to imagine a character as a famous personality. If he's a tough guy, for example, does he talk like Robert DeNiro, Humphrey Bogart, or Marlon Brando? Using a famous character's speech patterns as a guide is a good way to get started with the writing process. Hopefully, the character will take on a life of his or her own and diverge from the guide. If you base your character on a famous personality, however, you will need to be careful with voice castingdon't have your actors imitate the voice as well. (Unless, of course, you're doing a parody.)

One problem that happens time and time again is too much dialogue. Long stretches of dialogue can eat up valuable screen time. Unless the dialogue is extremely well directed and acted, it can also drag down the quality of a film. While this is not a hard-and-fast rule, most animation benefits from short, snappy dialogue. A sentence or two per character is usually all that is needed to cover the action and keep the film moving along. Short bits of dialogue are also easier to direct and animate. If a character needs to speak paragraphs, it had better be for a very good reason. One rule of thumb in live action is that the audience's attention span is only about 20 seconds. Try listening to any speech that goes on for more than that without drifting. Since animation usually moves along faster than live action, the attention span is even shorter.

Visualizing Your Story

At this point, in addition to writing the script, you'll need to be visualizing how the film will look. Animation is a very visual medium, so you will absolutely need to see how your film looks in every shot. Even if you draw in stick figures, sketching out your ideas in storyboard form will help you understand exactly how the gags and situations in your film will be staged.

The key here is to block out the film, not make pretty pictures. Accuracy in the look of the characters is less important at this stage than the composition and flow of the film as a whole. As long as the storyboard conveys the idea, it doesn't matter what it looks likeespecially if it's only for your own use. It is also easy to fall in love with the drawing of a bad shot because of the time investment. If a client needs to see "clean" boards, do them after you've worked out the details.

As you create the boards, take the opportunity to look for holes in the story, or possible gags. You may find that certain gags that sounded great in your script don't work visually, and it is much better, and cheaper, to make that cut now, rather than when the film is complete.

While sketching storyboard panels can be very quick for some people, others have problems with drawing. Drawing 3D characters by hand might be less accurate, as the drawings might not be true to the actual characters. If your characters are already built, you can visualize the story in another way, without drawing. Simply pose the characters in your 3D application, and render stills to use as the storyboard. No scanning is required, the images are true to the actual characters, and the 3D scene files can be saved and used later as layouts for animation.

Chapter One. Basics of Character Design

- Chapter One. Basics of Character Design

- Approaching Design as an Artist

- Design Styles

- Designing a Character

- Finalizing Your Design

Chapter Two. Modeling Characters

Chapter Three. Rigging Characters

- Chapter Three. Rigging Characters

- Hierarchies and Character Animation

- Facial Rigging

- Mesh Deformation

- Refining Rigs

- Conclusion

Chapter Four. Basics of Animation

- Chapter Four. Basics of Animation

- Understanding Motion

- Animation Interfaces

- The Language of Movement

- Secondary Action

- Conclusion

Chapter Five. Creating Strong Poses

- Chapter Five. Creating Strong Poses

- Posing the Body Naturally

- Creating Appealing Poses

- Animating with Poses

- Conclusion

Chapter Six. Walking and Locomotion

- Chapter Six. Walking and Locomotion

- The Mechanics of Walking

- Animating Walks

- Beyond Walking

- Adding Personality to a Walk

- Transitions

- Conclusion

Chapter Seven. Facial and Dialogue Animation

Chapter Eight. Animal Motion

Chapter Nine. Acting

- Chapter Nine. Acting

- Acting Vs. Animating

- Acting and Story

- Acting Technique

- Acting and the Body

- Other Techniques

- Conclusion

Chapter Ten. Directing and Filmmaking

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 84

- An Emerging Strategy for E-Business IT Governance

- Assessing Business-IT Alignment Maturity

- A View on Knowledge Management: Utilizing a Balanced Scorecard Methodology for Analyzing Knowledge Metrics

- Technical Issues Related to IT Governance Tactics: Product Metrics, Measurements and Process Control

- Managing IT Functions