Governance Structures for IT in the Health Care Industry

Reima Suomi

Turku School of Economics and Business Administration, Finland

Jarmo Thkp

Turku School of Economics and Business Administration, Finland

Copyright 2004, Idea Group Inc. Copying or distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of Idea Group Inc. is prohibited.

Abstract

In this chapter we bind together three elements: governance structures, the health care industry and modern information and communication technology (ICT). Our hypothesis is that modern ICT has even more than before made the concept and operation of the governance structures important. ICT supports some governance structures in health care better than others, and ICT itself needs governing. Our research question also is: which kinds of governance structures in health care are supported and needed by modern ICT?

Our chapter should be of primary interest for Health Care professionals. They should be given a new, partly revolutionary point of view to their own industry. For parties discussing governance structure issues in Health Care, the chapter should give a lot of support for argumentation and thinking. The models and conclusions should be extendable to other industries too. For academic researchers in Governance Structure and IT issues, the chapter should contain an interesting industry case.

Introduction

The pressures for the Health Care industry are well known and very similar in all developed countries: altering population, shortage of resources as it comes both to staff and financial resources from the taxpayers, higher sensitivity of the population for health issues, and new and emerging diseases, just to name a few. Underdeveloped countries dwell with different problems, but have the advantage of being able to learn from the lessons and actions the developed countries made already maybe decades ago. On the other hand, many solutions also exist, but they all make the environment even more difficult to manage: possibilities of networking, booming medical and health-related research and knowledge produced by it, alternative care-taking solutions, new and expensive treats and medicines, promises of the biotechnology…you name it (Suomi, 2000).

From the public authorities' point of view the solution might be easy: outsource as much as you can out of this mess. Usually the first ones to go are marginal operational activities, such as laundry, cleaning and catering services. It is easy to add information systems to this list, but we believe this is often done without a careful enough consideration. Outsourcing is too often seen as a trendy, obvious and easy solution, which has been supported by financial facts on the short run. Many examples, however, show that even in basic operations support outsourcing can become a costly option, not to speak of lost possibilities for organizational learning and competitive positioning through mastering of information technology.

In our chapter, we discuss the role of IT in Health Care, and focus on the question, "Which governance structure(s) are best suited for managing IT within the Health Care industry?" Our basic hypothesis is that information is a key resource for Health Care and that the managing of it is a core competence for the industry (Suomi, 2001).

Our analysis is restricted to public primary Health Care. We maintain that the governance problems are most acute there, because of several reasons. First, here the total spectrum of different customers and diseases is met. No customers can be selected or neglected, but all are entitled to some basic level of care. Possibilities to collect more resources, say through customer fees or through financial market operations, are limited (Suomi & Kastu-Hiki, 1998). As compared to special care units, the activities are fragmented and performed in smaller, less well-equipped units. As compared to the private sector, commercial thinking is less mature: outsourcing for commercial actors in the Health Care industry is a natural topic, as the private companies themselves are just the ones to whom activities are outsourced.

Our chapter shortly discusses two case examples — the primary Health Care in a small and in a middle-sized city — that are reported in closer detail elsewhere (Holm, Thkp, & Suomi, 2000; Suomi, Thkp, & Holm, 2001; Thkp, Suomi, & Holm, 2001; Thkp, Turunen, & Kangas, 1999). Here we aim at showing how the concepts we introduce are reflected in the reality. Picking out two different cases also serves the goal of discussing the competences and resources needed for outsourcing IT activities. Our message is that keeping the IT activities in-house demands certain resources and skills, but similarly outsourcing them cannot happen without any own resources and skills dedicated for this purpose. We discuss the situation of small entities that seem to be stuck in a dead-end situation: not enough expertise and resources either for in- or outsourcing.

The Concept of Governance Structure

The concept of a governance structure is by no means settled or well defined. We define a governance structure here as:

"A structure giving meaning and rules to an exchange relationship."

Lately we have seen many writings simply stating that governance structure is the same thing as management. Governance issues would be those of management issues. We strongly believe and stress that management is a different concept from governance structures, when of course management is needed in the case of governance structures, and governance structures also exist in management.

Our definition above conveys many details. First, the term structure refers to something stable that will last over a period. Governance structures are sure to change over time, but economizing exchange relationships necessitates that governance structures are of lasting nature. Should governance structures change all the time, no exchange relationship would be on a permanent basis.

With meaning and rules we refer both to the motivation and guidance functions of exchange relationships. As governance structures are there to guide exchange relationships, it is natural to expect that they try to foster them. As meaning refers to something meaningful, governance structures of course try to eliminate negative behavioral effects in exchange relationships, such as opportunism (Conner & Prahalad, 1996; Dickerson, 1998; Genefke & Bukh, 1997; Lyons & Mehta, 1997; Nooteboom, 1996), bounded rationality (Simon, 1991) and information asymmetry (Seidmann & Sundararajan, 1997; Wang & Barron, 1995; Xiao, Powell, & Dodgson, 1998), moral hazard (Jeon, 1996), and small numbers bargaining or negative network externalities (Kauffman, McAndrews, & Wang, 2000; Koski, 1999; Shapiro & Varian, 1999).

The rules or guidance functions contain three types of entities:

- rules on how an exchange relationship can be entered,

- rules on how to perform an exchange relationship,

- rules on how to control and follow-up an exchange relationship.

For example, certain exchange relationships can be reserved just for qualified partners. Just certified partners are entitled to run many transactions, say buy and sell options in stock exchanges or sell medicines. Rules on how to perform exchange relationships can be many and detailed. As a control mechanism should be seen as a permanent entity, it should have some control mechanisms that will foster successful exchange relationships and eliminate bad exchange relationships on the long run. To take a fanciful example, the www-site looking for flawed health care information Quackwatch (see Quackwatch www-site, 2003) is an example or guidance functions of an exchange relationship.

Finally, the exchange relationship can be understood in many ways. First, an exchange relationship can be seen as a transaction, where the relationship between the transaction partners is usually both short and well defined. The other end of the continuum is a long-term relationship. Further, the exchange relationship can be onerous, or happen without any visible or instant payment. The object of the exchange relationship can be any, including information, which role of course gains in importance in the information society.

Missing governance structures can be a major problem. Take for example the Eastern European transition economics. Missing regulations and infrastructure elements severely hamper trade and any exchange relationships, as for example documented in Kangas (1999). The same is true for the new e-business, where many environmental factors for exchange relationships still are underdeveloped, making actions in the new economy risky ones.

This leads us to ask who is responsible for the governance structures. We must differentiate between obligatory and selected governance structures. Obligatory governance structures are something that must be taken into account and cannot be omitted. Binding legislation is a good example. Selected governance structures are picked up by the exchange relationship parties themselves. For example, exchange partners can select which channel (for example an information system) to use in the exchange, and for example in which currency the transaction will be settled.

Governance structures exist in many levels. Any exchange relation between two parties needs some kind of governance structure. Even when organizing their own personal activities, people naturally use some kind of reference frame, a governance structure. A governance structure has a relation to the roles individuals carry. The same person is sure to behave differently, also to have different governance structures for exchange relationships, say in the roles of a husband, father or boss. Running the analysis on an organizational level, we can differentiate between intra- and interorganizational governance structures.

Governance structures are used in many disciplines. Naturally the topic suits to political science, where government of the citizens and organizations is a central topic. Economics is a natural place to study governance structures, and here it is very much about economizing exchange transactions (Williamson, 1985; Williamson, 1989); typical examples can be seen in Madhok (1996) and Mylonopoulos and Ormerod (1995). The most diverse and recent application area is management, including information systems management, where governance structures can be applied in many ways. As we discuss contracts, law is a natural background too. On the contrary to the tradition in economics, in management governance structures are not just used for economising purposes, but exchange relationships can be seen as tools for many organizational goals. Typical managerial problems are resource allocation (Loh & Venkatraman, 1993), eliminating risks in exchange relationships (Nooteboom, Berger, & Noorderhaven, 1997), motivating organizational stakeholders (Hambrick & Jackson, 2000; Peterson, 2000) or building trust in exchange relationships (Calton & Lad, 1995; Nooteboom, 1996).

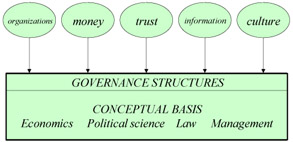

There are some major tools to establish governance structures. At the national and international level, legislation is the key concept. At an individual exchange relationship level, there is usually a contract defining the exchange relationship. Organizations are strong mechanisms to cover exchange relationships inside them. Fluent exchange relationships are made possible by information (and information systems), money, trust and cultural customs, such as organizational culture or trading conventions within an industry. These are also all elements of governance structures.

Using the term "governance structure" is by no means new in the health care sector. Pelletier-Fleury and Fargeon have used the concept in connection with the process of diffusion of telemedicine (Pelletier-Fleury & Fargeon, 1997). Spanjers et al. have studied the general networking or governance structure strategies of hospitals (Spanjers, Smiths, & Hasselbring, 2001). Further, Donaldson and Gray (1998) discuss how quality can be maintained through the smart design of governance structures. There is a rich research tradition on the new opportunities modern ICT offers for organizing health care; see for example Suomi (2001).

Figure 1: The Main Tools to Affect Governance Structures and Disciplines Providing the Conceptual Basis for Studying Them

Tools for Analyzing Governance Structures

In this section, we shortly discuss three disciplines to study governance structures. They are handpicked and surely do not cater for all the possibilities of analyzing governance structures. The first and most classic is that of transaction costs. Agency cost concepts are closely linked to those in the transaction cost analysis. An established concept is also that of a value chain. Finally, trust as an element in governance structures is shortly touched upon.

Transaction Costs

The transaction cost approach (TCA) is founded upon the following assumptions (Williamson, 1985):

- The transaction is the basic unit of analysis.

- Any problem that can be posed directly or indirectly as a contracting problem is usefully investigated in transaction cost economizing terms.

- Transaction cost economics are realized by assigning transactions (which differ in their attributes) to governance structures (which are the organizational frameworks within which the integrity of contractual relation is decided) in a discriminating way. Accordingly:

- the defining attributes of transactions need to be identified,

- the incentive and adaptive attributes of alternative governance structures need to be described.

- Although marginal analysis is sometimes employed, implementing transaction cost economics mainly involves a comparative institutional assessment of discrete institutional alternatives — of which classical market contracting is located at one extreme; centralized, hierarchical organization is located at the other; and mixed modes of firm and market organization are located in between.

- Any attempt to deal seriously with the study of economic organization must come to terms with the combined ramifications of bounded rationality and conjunction with a condition of asset specificity.

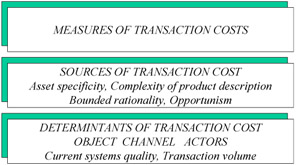

A very central concept is that of a transaction cost. Transaction is a difficult concept that materializes in several levels (Figure 2). First, each transaction has its exchange object(s), actors performing the transaction, and some channel(s) through which the transaction is performed. These offer the basic ramifications for any transaction and its associated transaction costs. In general, transactions tend to be more fluent the better the channel for them and the more voluminous they are. In literature, the main conceptual reasons for transaction costs are those of asset specificity, complexity of product description, bounded rationality and opportunistic behaviour. From the concepts, there is still a long way to the actual measurement of transaction costs, which is a difficult task.

Figure 2: A Tri-Level Transaction Cost Framework

The basic distinction of TCA among different organizational forms is the distinction between markets and hierarchies (Coase, 1937), which are forms of economic organizations. Given the division of labor, economic organizations control and coordinate human activities.

A market is an assemblage of persons which tries to arrange the exchange of property, where prices serve as both coordinating guides and incentives to producers in affecting what and how much they produce — as well as the amount they demand. At the equilibrium free-market price, the amounts produced equal the amounts demanded — without a central omniscient authority (Alchian & Allen, 1977).

In a hierarchy (firm) market transactions are eliminated and in place of the market structure with exchange transactions we find the entrepreneur-coordinator, the authority who directs production (Coase, 1937).

In addition to these two basic forms of organizational design, research on the subject has produced several sub-forms of organizations.

In the early days of transaction cost approach, the focus was mostly on hierarchies, as this was the dominant governance structure. An example of this focus is A.D. Chandler's division of hierarchies into multidivisional and unidivisional structures (Chandler, 1966).

The most important of the current developments of organization forms is the concept of groups or clans by Ouchi (1980). He breaks down hierarchies into bureaucracies and clans. These two organizational forms differ in their congruence of goals. Clans have a higher goal congruence than bureaucracies, and thus are further along in their attempt to eliminate transaction costs.

Cooperative behavior among firms is the root of many success stories of today's management (Jarillo, 1988). Like many other authors, he calls for a generally accepted framework for the study of inter-organizational systems. His contribution to the framework formulation is the concept of a strategic network. In discussing markets and hierarchies, he further divides markets into two segments, the segments of "classic market" and "strategic network". The difference between these two concepts lies in how transactions are organized: they can be based on competition or on cooperation, respectively.

Thomas Malone introduces several other organizational designs. He studies organizational forms and their effects on production, coordination, and vulnerability costs. Focusing on the internal organization of a firm, he introduces the following organizational designs (Malone, 1987):

- product hierarchy,

- decentralized market,

- centralized market,

- functional hierarchy.

In a product hierarchy, divisions are formed along product lines. In a functional hierarchy, similar processors are pooled in functional departments and shared among participants. In the realm of decentralized markets, different kinds of processors can be freely acquired from the market: processors supplied by different organizational units can be freely interchanged. In the case of centralized markets, freedom to choose remains but all processors must be collected from the same place.

We can further differentiate between six types of transaction costs (Casson, 1982):

- information costs,

- costs caused by requirement analysis,

- costs caused by negotiating,

- costs caused by initiating the transaction,

- costs caused by monitoring the transaction,

- costs caused by making the transaction legal.

The Value Chain

One of the most established governance structure concepts is that of the value chain as presented in Porter (1985). Since then the concept has been widely used, but has also awakened a lot of critique for its simplicity. The basic idea of the value chain is a one-directional flow of material and information in a production process. The value chain emphasizes the resources needed for production, but does not mention information or information systems, at least not explicitly. Analysis of the flows of information, money and physical goods is a key task for understanding any exchange transaction.

The strength of the value chain is its simplicity. It paved the way to the thinking that organizations should concentrate on the main value-adding activities, later called core competencies. The weakness of the value chain lies in its one-direction flow of activities. The value chain is unable to explain complicated market-based interactions, not to speak of modern virtual organizations.

The value chain helps individual participants in exchange relationships to understand their place in the totality. It is too strong in focusing attention to the value-adding elements of any exchange relationship, calling for less attention to those traits that do not add value to the exchange relationship.

Trust

Trust is a general concept usable in all human activity. It is present in some way, most visibly when absent, in all exchange relationships. We can define it as a one- or two-direction relationship between a human and a system, which according to Checkland (1981) can be one of the following:

- Natural system, including human,

- Designed activity system,

- Designed abstract system,

- Designed technical system,

- Transcendental system.

With the two first ones, the Trust relationship can materialize in two directions. You can trust a natural system and a designed activity system, and that one can trust you. Trust might be defined as an individualistic feature of human relations. Even in case of Trust existence as interorganizational Trust, de facto it is Trust between those organizations' managers and their staff consultants. Here we would like to refer to Berger (1991): "The most important experience of others takes place in the face-to-face situation, which is the prototypical case of social interaction. All the other cases are derivatives of it."

In transaction cost economics, Trust is not a key concept. However, the discipline puts emphasis on at least two dysfunctional phenomena that exist in a transaction if Trust is absent: Opportunism, Moral hazard.

In this connection, Trust is a key element in the fight against transaction costs. As Thompson (1967) cites: "Information technology belongs to those technologies, like the telephone and money itself, which reduce the cost of organizing by making exchanges more efficient." We might add, "Trust belongs to those technologies, like the telephone, information technology and the money itself, which reduce the cost of organizing by making exchanges more efficient."

We summarize the basic conceptual tools usable for studying governance structures in Table 1.

|

The transaction cost approach

|

|

The value chain model

|

|

Trust

|

Trends and Pressures in the Health Care Industry in Europe

In the European region, as also in the rest of the world, the health systems and services are undergoing a major transformation as a consequence of changes in age structures, social imbalance, increase in unhealthy lifestyles and new diseases. Fundamental differences between countries and especially between Western and Eastern European countries and their health problems have emerged. EU published a report (The State of Health in the European Community, 1996) about the state of the health in 1996 in which a few main features in development of population in EU region were discovered: fewer children, more older people, people live longer and differences persist between countries and regions. Especially the difference in life expectancy between the Western and Eastern European countries was highlighted in the report, as well as in the European Health report 2002 by World Health Organization (WHO) (The European Health Report, 2002). The difference of the share of population living below the poverty line is considerable between these countries. Poverty has a clear effect for the upward amount of illnesses due to communicable diseases (HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis) in the Eastern Europe. In the Western Europe the non-communicable diseases (e.g., cardiovascular diseases, cancer, neuropsychiatric disorders, overweight) account for about 75% of the burden of ill health and constitute a "pan-European epidemic". In addition to the concept of Digital Divide (Compaine, 2001; Norris, 2001) we can also well establish the concept of "Health Divide".

In the Communication on the development of Public Health Policy (OECD, 2003) EU has defined the following challenges facing the Member States: "Health care systems in the Member States are subject to conflicting pressures. Rising costs due to demographic factors, new technologies and increased public expectations are pulling in one direction. System reforms, greater efficiencies and increased competition are pulling in another. Member States must manage these conflicting pressures without losing sight of the importance of health to people's well-being and the economic importance of the health systems."

This Communication points out several important challenges, but in economic perspective, rising costs and the economic importance of the health system are especially interesting. Further, in discussion about technological and other supply-driven developments the Communication brings out the management issues. "Computerisation and networking, including the implementation of health care telematics, may help reduce health costs, particularly in relation to the management of health care."

The increasing costs have driven countries to develop and find new solutions in organizing their health care but still retaining the high standards and availability. Reorganizing functions and processes, new strategies, information systems and management issues play an important role in this effort. WHO has found four trends in organizing health services in Europe (The European Health Report, 2002):

- Countries are striving for better balance sustainability and solidarity in financing. Especially in the Western countries the solidarity is kept at a relatively high level.

- There is an increasing trend towards strategic purchasing as a way of allocating resources to providers to maximize health gain. Those are e.g.:

- Separating provider and purchaser functions,

- Moving from passive reimbursement to proactive purchasing,

- Selecting providers according their cost-effectiveness,

- Effective purchasing is based on contracting mechanism and performance-based payment.

- Countries are adopting more aggressively updated or new strategies to improve efficiency in health service delivery.

- Effective stewardship is proving central to the success of health system reform. This role (health policy, leadership, appropriate regulation, effective intelligence) is usually played by governments but it can also involve other bodies such as professional organizations.

Issues like financing problems, management strategies, provider-purchaser models and professional economical management are not the concepts which have been under very close attention in health care. The late adoption of these concepts have resulted that health care organizations are still in relatively early stages in learning to internalize them. The boost for the adoption is mostly the result of a serious recession in economics in the 1990s, which forced also public organizations — including health care — to consider issues like effectiveness. Before that, health care did by no means waste money or resources but those were not as scarce as today.

In the business environment effectiveness has been a central mantra for decades; mostly, therefore, these concepts were adopted from there. However, business environment is quite different in many ways, which don't make the adoption any easier. The differences can be seen to originate already from research paradigms, which are different, e.g., in medicine and business economics. The paradigms have influence on education and through that also to the professions and are therefore deep in organizations and difficult to change (Turunen, 2001).

Although it is also a consequence of the effectiveness demand, increased use of information and communication technology can be seen as a trend as well. In health care there can be seen several trends and visions about the increased use of ICT. After the use of ICT started almost from scratch in the beginning 1990s it has increased exponentially.

One of the most visible and effective trends has been the introduction of electronic patient record (EPR) systems, which are widely in use today. For example in Finland about 63% of public health care organizations use EPRs and the number is increasing rapidly. Use of electronic records has several advantages like easier and faster access to customer information, and information is in real time and thus the reliability of information is better. However, most of the advantages are still most likely not yet achieved. E.g., though implementation of systems is successful, organizations have mostly failed in renewing their processes which new systems enable and require to become effective. Another nation-wide attempt in Finland is to integrate the local systems to one nation-wide system where the information of patient is available for the clinician regardless of time or place.

Another interesting trend caused by increased electronic health information is the use of Internet. Health information is one of the most frequently sought topics on the Internet, with more than 40% of all Internet users. It is second in popularity after pornography (Nicholas, Huntington, Williams, & Jordan, 2002). Increased use of the Internet has surfaced also the question about reliability of the information acquired. Reliability is also concerning electronic systems in health care organizations. Along with the increased use of electronic health information, also organizations assessing that information have increased. Organizations like Health on the Net Foundation (HON) assess information on the Internet. National and international example is Finnish organization FinOHTA, which supports and coordinates health care technology assessment and distributes both national and international assessment results within the health care system (Jrvelin, 2002).

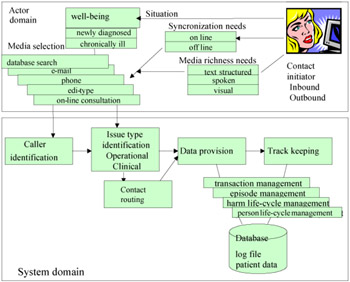

Internet has advanced also the use of different types of call, contact and communication centres. Those are established in an attempt to concentrate some of the services on one place including usually phone or Internet contacts. Centralizing certain services in one place should bring the advance for both to the patient when she/he can contact one place to get service, and to the organization that can offer information through phone or Internet and thus avoid unnecessary visits to doctors or nurses. One of the best-known examples of these services is in UK offered by NHS (NHS Direct Online). In Figure 3 we present a conceptual model of a call centre. Without going into details, in the figure we can see that the usage pattern of a call centre is dictated by the users (actor domain) and by the functionalities built in the system (system domain). For more information on the model, see Suomi and Thkp (2003).

Figure 3: A Conceptual Model of a Call Centre in Health Care (Adopted from Suomi & Thkp, 2003)

A current trend in the health care technology can be seen in the use of mobile technology in communication between the patient and the clinician. Sending and receiving information through mobile phone is however still quite clumsy and the benefits of the use of it are not yet fully proven. Wireless communication is however in use, e.g., in hospitals and health centres where doctors use portable computers in their daily visits to the wards to get access in patient health records online.

There are several other trends and visions about use of ICT in health care (like use of digital images) which are not mentioned here (Table 2). However, the basis of the use of ICT seems to be the use of an integrated database, like EPR, in which all the information about a single patient is integrated so that it is available for the clinicians in their decision-making despite the time or location. The EPRs in use today are not yet able to offer all the required information from one application.

|

However, two trends or visions are certain: First, the pressure for more effective organizations is not going to diminish in health care for the next few decades and new solutions, forms of organizations and methods have to be searched for. Second, once the health care industry got off the ground in using ICT, it is not going to diminish its use, and therefore the development of new technology for health care is going to increase ever faster (as in most of the other industries too) and governance structures and management issues are going to play ever-increasing roles in trying to get all the benefits from it.

The Public Private Health Care Governance Issue

In this section we discuss the different role of private and public health care and the differences in their management and governance structures. The aim is to sketch the complexity of public sector health care governance issues. This issue is made even more complex through the recent adoption of market thinking, business originated strategies and competition discussion in the sector.

When organizing the services, public and private health care use quite similar processes at the operational level. The visit to a nurse or a doctor because of flu or fracture generates very much similar processes and transactions both in the public and in the private sector. The same information and materials are needed in both organizations to cure the illness so you could claim that the value chain is similar and produces the same value to the organization and to the patient. The differences appear of course in money flows, but the basic cure process is very much the same.

However, when the organizations are studied at the upper, strategic level, the difference of the governance structures starts to appear. The public and private sectors differ from each other in several ways in terms of goals, decision-making, fund allocations, job satisfaction, accountability and performance evaluation. Typically public organizations have little flexibility in terms of fund allocations and very little incentive to be innovative. Rigid procedures, structured decision making, dependence on politics, high accountability by public and administration, and temporary and politically dependent appointments are features connected to public sector organizations and employees (Aggarwal & Mirani, 1999).

The private sector has different goals as they seek to enhance stakeholders' value and maximize profits. They are more flexible than public organizations in terms of budget allocation, personnel decisions and organizational procedures. Merit and award systems are mostly well defined and new ideas that maximize firms' value are encouraged (Aggarwal & Rezaee, 1995).

As these definitions show, the difference is high, especially in organizing activities. While the public sector has to follow strict rules, private companies can organise their activities according to the market situation. When we look at the definition of governance structure and the words meaning and rules in it, the importance of the latter is very big in the public sector. Most exchange relations have to follow strict rules, say especially in purchasing: the public organizations have to organise a public competitive bidding when purchasing services or goods above a certain value.

On the other hand the word meaning has probably a stronger emphasis in the private sector. Public health care organizations are guided by national politics and political decisions, which may be well thought of, but which anyway are given from above and which are thus more distant and abstract than strategies built by the organizations themselves.

However, because of several changes in political and economic environments as well as the changes in technology, public sector is facing the same uncertain and turbulent environment as the private sector has always faced. In this new environment, public sector organizations are expected to exhibit many features usually seen in the private sector, including some scope of entrepreneurial behaviour. This shift has not been totally accepted in the public sector and there is a concern that the application of the language of consumerism, the contract culture, excess performance management and the use of quasi markets might create problems. It is argued that all these need to be balanced by approaches that recognize the value of the public sector (White, 2000). The complexity is of course dependent also on the size of the organization. The larger the organization is, the more administrative information is included (Spil, 1998).

Increased complexity and turbulent environment refers to the changing structures of the public sector. Until the last decade the structures of the public sector have remained quite stabile because of governments' strong role in steering them. Starting from the 1980s, however, decentralization and local empowerment have also invaded the public health care sector. Therefore one could say that at the moment the structures in the public sector health care are not on a permanent basis — rather they are in a turbulent phase. It might be that effectiveness cannot be achieved in the public sector because of the ongoing turnover phase of the industry.

One distinctive difference between the public and private sector which cannot be bypassed since it greatly affects governance structures through management is the group of stakeholders the sectors have to satisfy. While the private sector is to maximize the profits of the owners (to use rough generalization), the public sector has more critical stakeholders. Of course neither in the private sector is this so simple as, e.g., employees are a strong stakeholder group with its own interests inside the organization. Employee demands cannot be set aside. And despite the differences managers must work in both organizations to find a point where most of the stakeholders are satisfied most of the time. In many cases increasing the satisfaction of one group of stakeholders decreases the satisfaction of others (Dolan, 1998). This affects the structure of exchange relationships as the stakeholders eventually decide (consciously or unconsciously) whether the relationships the organization maintains are in accordance with their demands.

Another view to the public-private sector governance structure is to discuss the issue from a national perspective. The private and public sectors share the health care markets and the national government and legislation have a great effect on those shares. The obligatory governance structures play an essential, role especially in the public sector: they have many responsibilities that they cannot escape. Next we will describe some features of the roles and market shares of public and private health care using Finland as an example.

All health care services are financed mostly (60%–80%) from the state or municipal taxation and the remainder from the National Insurance Scheme (10%–20%) and co-payments. The private health care sector is seen more or less as complementing rather than competing against the public health care. The markets for the private sector have established themselves slowly, mainly because of the extensive role of the public services. By 1996 the share of private doctor consultation in Finland was 16% of all doctor consultations and the share of doctors who practice solely in the private sector was 5%. The total share of private health care services was 22%. The private sector has the strongest market share in general practice visits, dentist and physiotherapist services and in employee health services.

In Finland health care authorities at the local level have gained more independence in organizing their governance structures since the state subsidiary system changed in 1997. Earlier the rule was that local public health care should produce primary care as an internal service and that the state subsidy was granted on the bases of population, morbidity, population density and land area. Since 1997 the criteria were changed and local authorities gained more independence in organizing the services according to the local needs. They were encouraged to use methods and approaches familiar from the private sector business environment.

Some opposite developments have been seen at the international level. In European countries the need to strengthen the stewardship role of the state appeared with the introduction of new market mechanisms and the new balance between the state and market in health systems. Thus, policy makers have sought to steer these market incentives to achievement of social objectives (The European Health Report, 2002).

The government's target is therefore both to increase the independence but at the same time to steer the development. This is a hybrid form of market and hierarchies where the market works with the rules set by an entrepreneur-coordinator (government) who directs the production (transactions).

IT Sourcing Governance Issues

Outsourcing is seen in many organizations as a means to get rid of everything unpleasant or unknown. The solution is in some cases good but in some cases it is also a way to lose even the last understanding and control of the outsourced activity. The solution is not as simple as it might sound. Many firms have made sourcing decisions based just on anticipated cost saving without further consideration of its effects on strategies of technological issues (Kern & Wilcocks, 2000).

IT outsourcing can be defined in the following way (Kern & Wilcocks, 2000): "IT outsourcing can be defined as a decision taken by an organization to contract out or sell the organization's IT assets, people, and/or activities to a third-party vendor, who in exchange provides and manages assets and services for monetary returns over an agreed time period." Kern and Willcocks stress the significance of contract and control in their article. They further underline that "the client-vendor relationship is indeed more complex than a mere contractual transaction-based relationship." Also control is seen as an essential but complex issue in these relationships. IT outsourcing tends to be more complex than many other forms of outsourcing such as cleaning, catering or calculation of salaries because IT pervades, affects and shapes most organizational processes in some way (Kern & Willcocks, 2002).

The tools for analyzing the governance structures described earlier included the element of trust. Contracts are the ones with which the mistrust is tried to reduce. With a comprehensive and mutually agreed upon contract the trust can be improved but no matter how comprehensive it is, there is always a possibility to understand it in a different way than a partner. As trust is an individualistic feature of human relation, contract and especially its reading are a result of this feature: You (the individual) can interpret it to your own benefit if needed.

Thus, outsourcing needs first of all a good contract. Another main issue in outsourcing is control. As long as you have your information systems insourced the biggest concern is to control the professionals in the department. They have to be skilled, motivated and they have to have enough resources to perform their work. However, it is mostly the matter of technology and personnel management. Of course you have to also to ensure the quality of the outcome in a way that it serves the organization most effectively.

When outsourcing, the management loses a part of this control. Also new issues connected with trust like opportunism and moral hazard are emerging and those are a lot more difficult to control than just internal resources. In outsourcing the contract is juridical, done between two organizations, but the trust is always emerging (or not) between two individuals. Therefore choosing persons to negotiate and consummate an agreement is not a trivial case. In addition to that those persons have to be familiar with the technical and juridical issues of the contract, they have to have also some knowledge about human nature and knowledge about the meeting technique.

Governance Structures in ICT Sourcing Solutions

In this chapter we discuss two research cases that we conducted in the Finnish health care industry. The first case is about development of information management strategy for a small health care federation of municipalities. Creating a strategy for an organization is a typical internal project and suggests that there is a need to study the goals of the organization and structures with which it can achieve those goals. Internal governance structures are an essential part of this development. The second case is an extensive evaluation of a large information systems implementation project with outsourcing solutions. Outsourcing activities suggest that there is a need for developing and managing external governance structures. We also have two different types of cases to discuss governance structures. The purpose of this is to find out differences between medium and small size organizations and between internal and external governance structures and needs.

Case 1 Organizing the Internal Governance Structures of a Small Health Care Unit

In the first case two small municipalities compose a health care federation running a health centre to provide health care services for the population of some 13,000 people in the area. In the Finnish scale it presents a small organization, though a fairly typical one. The organization had used a new system for over a year including hardware, EPR and network. The patient records were earlier in manual form and the new EPR is the heart of the new information system of the organization. The implementation had gone well and the staff began to get acquainted with the system. However, problems started to appear after some time. They were not yet massive, but the management noticed that they did not have enough expertise to develop the system towards the goal of better supporting organization goals and strategies.

The organization had created a comprehensive business strategy, which the new system was supposed to support. One of the most important issues in the strategy was that the organization should be able to support the provider-purchaser model. The purchaser (the municipalities) expected to get a fixed per unit price for the services they buy. To be able to satisfy the purchasers the health care federation needed a system from which they could dig the required information to set the prices. In addition, the health care centre is expected to give an assessment of the level of demand for different health services by the population.

Our research team developed an information management strategy in co-operation with the management and the staff of the federation. The ultimate goal was to solve how the federation could manage its ICT development effectively to support and also to steer business strategy. The strategy development team included our research team (three researchers) and members from the management and from the staff (three to five persons) of the federation. The development team had meetings weekly. We carried out some 60 interviews including staff and management of the federation, management of municipalities, and vendors.

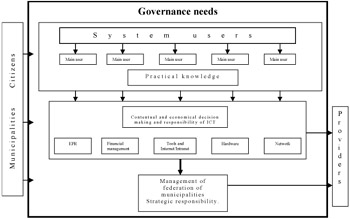

The starting point was that the governance structures to steer ICT functions were not clear and therefore one of the main goals was to develop those structures through creating a strategy for the management of ICT. The development needs were mostly intraorganizational (Figure 4). Although there were also problems in inter-organizational relationships, say in connections to the municipalities and to the system vendors, the problems in those relationships were mostly due to lack of clear internal organization to handle them.

Figure 4: The Governance Structure in the Insourcing Case

One of the first tasks was to solve the problem of responsibilities for different components of the system. The system had five clear areas (see Figure 4) and each of them was allocated an owner. Earlier the manager of the federation had that responsibility of all areas almost totally himself. Owners were selected from the management of the organization, and they had total responsibility over their areas. Main users who were links to the practice in different departments supported them. Main users were selected from the staff on the basis of their position, ICT knowledge and interest. The structure was primarily defined to clarify the organization of ICT management, but since ICT is the heart of the value chain, the work naturally served also the management of organization's value chain. In an information-intensive industry like health care the fluent flow of information can be "dead serious".

With defined responsibilities the organization had a clearer structure to manage ICT, which is crucial in any governance structure attempting to economize the exchange relationships. A structure should be lasting, so in our model the ownership is not bound to a person but to a position. The persons may change but the position is most likely going to remain. With the clear structure of system owners the information flows more efficiently also to the management. Achieving a lasting structure gave possibilities to define rules to manage it — a stable structure supports our main goal, setting up a decent information management strategy.

Exchange relationships with external stakeholders became also clearer. The organization had now a structure with rules with which it could handle relationships more effectively. Especially, relations to system vendors which were earlier haphazard, became now clearer. There was now a defined contact person for each part of the system and the contacts could be conducted through them. The structure also serves the guidance functions mentioned in our definition of governance structure earlier.

The case pointed out that even or better yet especially a small organization needs clear governance structures to handle various functions. In the transaction costs point of view the health care is moving from a hierarchy where market transactions are eliminated towards a market. This change has been fast and health care organizations have faced difficulties in adopting new ways of operating. Industry has not had enough time to adjust to new situation and organizations have tried to cope with old structures. The governance structures should be emphasized especially in the case of functions with high effect on processes and activities but with little expertise to handle them in the organization. ICT is naturally not a core business in any health care organization but affects almost every process and activity when implemented.

Case 2 Organizing the External Governance Structures of a Medium Sized Health Care Unit

In the second case the authors conducted evaluation research of the large information system implementation project called Primus during the year 2000. The project was executed in the public sector health care department in the fifth largest city of Finland. The Primus included four subprojects: EPR, telecommunications network, process development and three smaller development projects. The first two subprojects included the basic infrastructure solutions and were quite successfully implemented. The last two subprojects were more connected with the exchange relationships in daily health care, and were considerably more difficult to master. During the project, 800 users in 440 workstations began using the new patient record systems in about a hundred different units around the city's health care department. As in our previous case, also here the infrastructure and especially the EPR were in key roles. Before the project the patient records were in manual form.

Our evaluation research was divided in two parts. In the first part we evaluated the process, which led to the implementation of new ICT. We focused on management and strategic issues, negotiations, sourcing decisions, supportive issues (training, help desk) and technical solutions: aspects that were decided in the planning process of the project. The outsourcing solutions were also in close examination by the public. The network and maintenance of hardware was outsourced to a large Finnish teleoperator, which was a solution that did not satisfy everybody.

In the second part we evaluated the results of the project. The evaluation included the cost-benefit aspects and end user and patient satisfaction in order to assess how the project has influenced the activities of the organization. The research included 90 interviews, two questionnaires (staff and customers), two group interviews and one half-day seminar for interest groups. We had also meetings in research steering group at least once in a month.

During the evaluation project we also did some comparative research with a local private health care clinic. One of the main interests of comparative research was to find out which kind of organization held responsibility about ICT in the private sector and the governance structure they used.

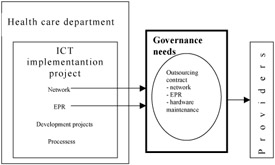

Although there were several functions in the implementation project, probably the most critical parts of it were outsourcing network, hardware maintenance and acquiring EPR (Figure 5). As said earlier, outsourcing does not mean that outsourced functions can be forgotten and left without attention. In our case organization there had not been earlier experience about outsourcing of such large technological solutions, and even nationwide the solution was a new in public health care environment. So there was no baseline determined from which the organization could have sought examples about structure or guidance for the solution. Outsourcing contract was agreed for a five-year period after which the outsourced services were set under public competition, so it can be considered as a long-term exchange relationship. New situations set high requirements for managing the relationships and new governance structures had to be created.

Figure 5: The Governance Structure in the Outsourcing Case

In such contracts, the rules and guidance functions play extremely important roles. From our determination earlier the rules on how to perform an exchange relationship and especially how to control and follow-up an exchange relationship are most vital. Without strict rules the transaction cost can rise unexpectedly high. In Figure 2, the sources of transaction cost are mentioned: complexity of product, opportunism and bounded rationality. Opportunism is related also to trust. With contracts these elements can be eliminated to some extent, but not all of them, as we noted few times in our case. There were misunderstandings about maintenance level and responsibilities and especially with the software provider about corrections and new features in EPR. Problems and limitations in EPR caused problems in practical work.

Although these two cases are different in size and in research focus, they give an excellent opportunity to study the governance structures in public health care. Public health care organizations operate basically with the same rules and procedures. However, like was said earlier, the organization's size affects its complexity in administration. Complexity affects naturally also governance structures and the management. On the other hand, small organizations have less expertise to execute, e.g., ICT projects, and that lack makes the project complex even in that environment. Although the large organizations have more complex projects they also have more resources to solve them. We mentioned earlier also that the IT-outsourcing is more complex than many other forms of outsourcing since it pervades, affects and shapes most organization processes in some way and this is the case whether the organization is small or large.

The above is maybe a rough generalization, but comparing these two cases, in the smaller case the management was many times totally desperate since they had no expertise to solve problems and they were too small to put enough pressure for providers to have more attention. The larger organization was the largest customer to the system provider so the situation was completely different (not meaning that they did not have any problems). In these situations the contracts (rules) and trust become an essential in the governance structure perspective.

Since health care as industry has long traditions in organization and governance structures it is not easy to create new structures. However, also, health care has to learn to create and use new governance structures if it wants to keep up with the technological development. ICT facilitates and forces organizations to consider new governance structures, so in that way ICT is acting as a catalyst in renewing health care structures even deeper and wider than just ICT requires. Old structures are challenged and their existence is put under close examination.

In both cases, introduction of ICT challenged old governance structures and made it possible to introduce new structures. The smaller organization fought to find governance for the ICT internally, whereas the bigger organization made a risky outsourcing decision. The bigger organization had an opportunity to change general governance structures because of modern ICT, but this proved to be a difficult road to go.

Conclusion

A carefully and intelligently defined and implemented governance structure relieves organizations and their management of a lot of stress. However, in a constantly turbulent environment, no organization is a running machine that would not need maintenance. Governance structures are means to control exchange relationships, but in rare cases means to totally automate them. Especially in the popular outsourcing literature and marketing, outsourcing is pictured as a panacea of getting rid of management troubles — say in a complicated case of ICT management. As we however know, this responsibility of management cannot be escaped.

Exchange relationships are the value-adding activities of organizations. Governance structures give meaning and rules to them. Exchange relationships are there to add value to all partners, but unfortunately also contain costs and risks. For an exchange relationship to take place, the added value produced must be bigger than those of the transaction costs for each partner, taking into account also his/her/its risk profiles. In just a few simple transactions, the total outcome of the exchange can be counted beforehand, if even afterwards.

Value chains are a typical tool to analyze governance structures and exchange relationships happening in them. Their task is to show the total flow of activities, whether it is either the case of information, material or money. With a value chain, each individual actor can understand its place in the totality. Value chains are too valuable in their focus towards value-adding elements. Should an exchange relationship not add value to anybody, it should not happen. Governance structures should be there to eliminate nonvalue-adding elements from value chains. This is too often forgotten.

Trust is a concept that is currently heavily studied, but too seldom in the field of governance structures research and practice. For us to produce a metaphor, trust is the glue that keeps governance structures together and the crease that makes them fluently serve exchange transactions.

The pressures towards health care are many. Many of these pressures would have emerged despite ICT, but also in many cases ICT has even emphasized those pressures. On the other hand, ICT offers many new possibilities to build governance structures. Finally, ICT is a resource and exchange relationship field to be governed. ICT has also three roles in their relationship to governance structures:

- Emphasizer and visualizer of pressures towards governance structures in an industry, say health care,

- Facilitator of new governance structures to handle exchange relationships,

- An exchange relationship field to be governed.

Many see privatization as a panacea for all the problems in most industries, including health care. We do not however share this view. In many aspects private organizations are faster and more flexible in their activities, but health care too has many characteristics that cause that activities there cannot be solely left to market forces. This is not to say that public organizations should not try to learn the best practices from the private sector.

A whole book could be devoted to the discussion of health care ICT sourcing decisions. A fact seems to be that all health care organizations are compelled to outsource at least some ICT functions. They simply lack the expertise. In this sector, fine-tuned thinking is however needed, so that the core competencies of health care are not outsourced. Modern health care is anyway much about management of information about the patient, diseases and their cures. Infrastructure-oriented ICT tasks could and should be outsourced, but not the whole task of knowledge management.

|

Our cases handled two organizations of different sizes. The smaller one had even difficulties in finding resources to outsource basic ICT — even this process needs careful management. The bigger organization outsourced ICT infrastructure management and searched for possibilities to redesign governance structures in other fields. To some extent success was visible, but the number of available options seemed to be out of scope for the organization. Again, management time and energy was a scarce resource.

Section I - IT Governance Frameworks

- Structures, Processes and Relational Mechanisms for IT Governance

- Integration Strategies and Tactics for Information Technology Governance

- An Emerging Strategy for E-Business IT Governance

Section II - Performance Management as IT Governance Mechanism

- Assessing Business-IT Alignment Maturity

- Linking the IT Balanced Scorecard to the Business Objectives at a Major Canadian Financial Group

- Measuring and Managing E-Business Initiatives Through the Balanced Scorecard

- A View on Knowledge Management: Utilizing a Balanced Scorecard Methodology for Analyzing Knowledge Metrics

- Measuring ROI in E-Commerce Applications: Analysis to Action

- Technical Issues Related to IT Governance Tactics: Product Metrics, Measurements and Process Control

Section III - Other IT Governance Mechanisms

- Managing IT Functions

- Governing Information Technology Through COBIT

- Governance in IT Outsourcing Partnerships

Section IV - IT Governance in Action

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 182