Using XML Technologies

Overview

Building applications for the Internet means using protocols and creating browser-based user interfaces, as you've done in the preceding two chapters, but also opens an opportunity for exchanging business documents electronically. The emerging standards for this type of activity center around the XML document format and include the SOAP transmission protocol, XML schemas for the validation of documents, and XSL for rendering documents as HTML.

In this chapter, I'll discuss the core XML technologies and the extensive support Delphi has offered for them since version 6. Because XML knowledge is far from widespread, I'll provide a little introduction about each technology, but you should refer to books specifically devoted to them to learn more. In Chapter 23, I'll focus specifically on web services and SOAP.

Introducing XML

Extensible Markup Language (XML) is a simplified version of SGML and is getting a lot of attention in the IT world. XML is a markup language, meaning it uses symbols to describe its own content—in this case, tags consisting of specially defined text enclosed in angle brackets. It is extensible because it allows for free markers (in contrast, for example, to HTML, which has predefined markers). The XML language is a standard promoted by the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C). The XML Recommendation is at www.w3.org/TR/REC-xml.

XML has been touted as the ASCII of the year 2000, to indicate a simple and widespread technology and also to indicate that an XML document is a plain-text file (optionally with Unicode characters instead of plain ASCII text). The important characteristic of XML is that it is descriptive, because every tag has an almost human-readable name. Here is an example, in case you've never seen an XML document:

Mastering Delphi 7 Cantu Sybex

XML has a few disadvantages I want to underline from the beginning. The biggest is that without a formal description, a document is worth little. If you want to exchange documents with another company, you must agree on what each tag means and also on the semantic meaning of the content. (For example, when you have a quantity, you have to agree on the measurement system or include it in the document.) Another disadvantage is that XML documents are much larger than other formats; using strings for numbers, for example, is far from efficient, and the repeated opening and closing tags eat up a lot of space. The good news is that XML compresses well, for the same reason.

Core XML Syntax

A few technical elements of XML are worth knowing before we discuss its usage in Delphi. Here is a short summary of the key elements of the XML syntax:

- White space (including the space character, carriage return, line feed, and tabs) is generally ignored (as in an HTML document). It is important to format an XML document to make it readable by a human being, but your programs won't care much.

- You can add comments within markers, which are basically ignored by XML processors. There are also directives and processing instructions, enclosed within and ?> markers.

- There a few special or reserved characters you cannot use in the text. The only two symbols you can never use are the less-than character (or left angle bracket, <, used to delimit a marker), which is replaced by <, and the ampersand character (&), which is replaced by &. Other optional special characters are > for the greater-than symbol (right angle bracket, >), ' for the single quote ('), and " for the double quote (").

- To add non-XML content (for example, binary information or a script), you can use a CDATA section, enclosed within and ]]>.

- All markers are enclosed by angle brackets, < and >. Markers are case sensitive (in contrast to HTML).

- For each opening marker, you must have a matching closing marker, denoted by an initial slash character:

value

- Markers must not overlap—they must be properly nested, as in the first line here (the second line is not correct):

xx yy // OK xx yy // WRONG

- If a marker has no content (but its presence is important), you can replace the opening and closing markers with a single marker that includes a final (trailing) slash: .

- Markers can have attributes, using multiple attribute names followed by a value enclosed within quotes:

- Any XML node can have multiple attributes, multiple embedded tags, and only one block of text, representing the value of the node. It is common practice for XML nodes to have either a textual value or embedded tags, and not both. Here is an example of the full syntax of a node:

value1 value2

- A node can have multiple child nodes with the same tag (tags need not be unique). Attribute names are unique for each node.

Well Formed XML

The elements discussed in the previous section define the syntax of an XML document, but they are not enough. An XML document is considered syntactically correct, or well formed, if it follows a few extra rules. Notice that this type of check doesn't guarantee that the content of the document is meaningful—only that the tags are properly laid out.

Each document should have a prologue indicating that it is indeed an XML document, which version of XML it complies with, and possibly the type of character encoding. Here is an example:

Possible encodings include Unicode character sets (such as UTF-8, UTF-16, and UTF-32) and some ISO encodings (such as ISO-10646-xxx or ISO-8859-xxx). The prologue can also include external declarations, the schema used to validate the document, namespace declarations, an associated XSL file, and some internal entity declarations. Refer to XML documentation or books for more information about these topics.

An XML document is well formed if it has a prologue, has a proper syntax (see the rules in the previous section), and has a tree of nodes with a single root. Most tools (including Internet Explorer) check whether a document is well formed when loading it.

| Note |

XML is more formal and precise than HTML. The W3C is working on an XHTML standard that will make HTML documents XML compliant, for better processing with XML tools. This implies many changes in a typical HTML document, such as avoiding attributes with no values, adding all the closing markers (as in and ), adding the slash to stand-alone markers (asand ), proper nesting, and more. An HTML-to-XHTML converter called HTML Tidy is hosted by the W3C website at www.w3.org/People/Raggett/tidy/. |

Working with XML

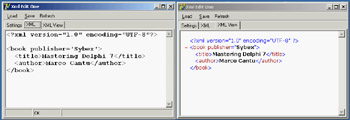

To get acquainted with the format of XML, you can use one of the existing XML editors available on the market (including Delphi itself and Context, a programmer's editor written in Delphi). When you load an XML document into Internet Explorer, you'll see whether it is correct and, in this case, you'll see it within the browser in a tree-like structure. (At the time I'm writing this, other browsers have more limited XML support.)

To speed up this type of operation, I've built the simplest XML editor I could come up with—basically a memo with XML syntax-checking and a browser attached to it. The XmlEditOne example has a PageControl with three pages. The first page, Settings, hosts a couple of components in which you can insert the path and the name of the file you want to work with. (The reason for not using a standard dialog will become clear when I show you an extension of the program.) The edit box hosting the complete filename is automatically updated with the path and filename, provided the AutoUpdate check box is selected.

The second page hosts a Memo control; the text of the XML file is loaded and saved by clicking the two toolbar buttons. As soon as you load the file, or each time you modify its text, its content is loaded into a DOM to let a parser check for its correctness (something that would be complex to do with your own code). To parse the code, I've used the XMLDocument component available in Delphi, which is basically a wrapper around a DOM available on the computer and indicated by its DOMVendor property. I'll discuss the use of this component in more detail in the next section. For the moment, suffice to say you can assign a string list to its XML property and activate it to let it parse the XML text and eventually report an error with an exception.

For this example, this behavior is far from good, because while typing the XML code you'll have temporarily incorrect XML. Still, I prefer not to ask the user to click a button to do the validation, but rather to let it run continuously. Because it is not possible to disable the parse exception raised by the XMLDocument component, I had to work at a lower level, extracting the DOMPersist property (referring to the persistency interface of the DOM) after extracting the IXMLDocumentAccess interface from the XMLDocument component (called XmlDoc in this code). You can also extract the IDOMParseError interface from the document component, to display any error message in the status bar:

procedure TFormXmlEdit.MemoXmlChange(Sender: TObject); var eParse: IDOMParseError; begin XmlDoc.Active := True; xmlBar.Panels[1].Text := 'OK'; xmlBar.Panels[2].Text := ''; (XmlDoc as IXMLDocumentAccess).DOMPersist.loadxml(MemoXml.Text); eParse := (XmlDoc.DOMDocument as IDOMParseError); if eParse.errorCode <> 0 then with eParse do begin xmlBar.Panels[1].Text := 'Error in: ' + IntToStr (Line) + '.' + IntToStr (LinePos); xmlBar.Panels[2].Text := SrcText + ': ' + Reason; end; end;

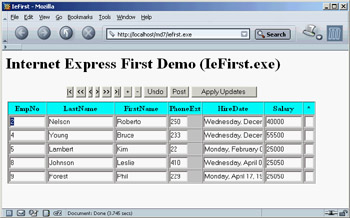

You can see an example of the output of the program in Figure 22.1, alongside the XML tree view provided by the third page (for a correct document). The third page of the program is built using the WebBrowser component, which embeds Internet Explorer's ActiveX control. Unfortunately, there is no direct way to assign a string with the XML text to this control, so you'll have to save the file first and then move to its page to trigger the loading of the XML in the browser (after manually clicking the Refresh button at least once).

Figure 22.1: The XmlEditOne example allows you to enter XML text in a memo, indicating errors as you type, and shows the result in the embedded browser.

| Note |

I've used this code as a starting point to build a full-fledged XML editor called XmlTypist for a company I work with. It includes syntax highlighting, XSLT support, and a number of extra features. Refer to Appendix A, "Extra Delphi Tools by the Author" for the availability of this free XML editor. |

Managing XML Documents in Delphi

Now that you know the core elements of XML, we can begin discussing how to manage XML documents in Delphi programs (or in programs in general; some of the techniques discussed here go beyond the language used). There are two typical techniques for manipulating XML documents: using a Document Object Model (DOM) interface or using the Simple API for XML (SAX). The two approaches are quite different:

- The DOM loads the entire document into a hierarchical tree of nodes, allowing you to read them and manipulate them to change the document. For this reason, the DOM is suitable when you want to navigate the XML structure in memory and edit it, or for creating new documents from scratch.

- The SAX parses the document, firing an event for each element of the document without building a structure in memory. Once parsed by the SAX, the document is lost, but this operation is generally much faster than the construction of the DOM tree. Using the SAX is good for reading a document once—for example, if you're looking for a portion of its data.

There is a third classic way to manipulate (and specifically create) XML documents: string management. Creating a document by adding strings is the fastest operation, particularly if you can do a single pass (and don't need to modify nodes already generated). Even reading documents by means of string functions is very fast, but this process can become difficult for complex structures.

Besides these classic XML processing approaches, which are also available for other programming languages, Delphi provides two more techniques you should consider. The first is the definition of interfaces that map the document structure and are used to access the document instead of the generic DOM interface. As you'll see, this approach makes for faster coding and more robust applications. The second technique is the development of transformations that allow you to read a generic XML document into a ClientDataSet component or save the dataset into an XML file of a given structure (not the specific XML structure natively supported by the ClientDataSet or MyBase).

I won't try to fully assess which option is better suited for each type of document and manipulation, but I will highlight some of the advantages and disadvantages while discussing examples of each approach in the following sections. At the end of the chapter, I'll discuss the relative speed of techniques for processing large files.

Programming with the DOM

Because an XML document has a tree-like structure, loading an XML document into a tree in memory is a natural fit. This is what the DOM does. The DOM is a standard interface, so when you have written code that uses a DOM, you can switch DOM implementations without changing your source code (at least, if you haven't used any non-custom extensions).

In Delphi, you can install several DOM implementations, available as COM servers, and use their interfaces. One of the most commonly used DOM engines on Windows is the one provided by Microsoft as part of the MSXML SDK but also installed by Internet Explorer (and for this reason in all recent versions of Windows) and many other Microsoft applications. (With the full MSXML SDK also containing documentation and examples you don't get in other embedded installations of the same library.) Other DOM engines directly available in Delphi 7 include Apache Foundation's Xerces and the open-source OpenXML.

| Tip |

OpenXML is a native Object Pascal DOM available at www.philo.de/xml. Another native Delphi DOM is offered by TurboPower. These solutions offer two advantages: They don't require an external library for the program to execute, because the DOM component is compiled into your application; and they are cross-platform. |

Delphi embeds the DOM implementations into a wrapper component called XMLDocument. I used this component in the preceding example, but here I will examine its role in a more general way. The idea behind using this component instead of the DOM interface is that you remain more independent from the implementations and can work with some simplified methods, or helpers.

The DOM interface is complex to use. A document is a collection of nodes, each having a name, a text element, a collection of attributes, and a collection of child nodes. Each collection of nodes lets you access elements by position or search for them by name. Notice that the text within the tags of a node, if any, is rendered as a child of the node and listed in its collection of child nodes. The root node has some extra methods for creating new nodes, values, or attributes.

With Delphi's XMLDocument, you can work at two levels:

- At a lower level, you can use the DOMDocument property (of the IDOMDocument interface type) to access a standard W3C Document Object Model interface. The official DOM is defined in the xmldom unit and includes interfaces like IDOMNode, IDOMNodeList, IDOMAttr, IDOMElement, and IDOMText. With the official DOM interfaces, Delphi supports a lower-level but standard programming model. The DOM implementation is indicated by the XMLDocument component in the DOMVendor property.

- As a higher-level alternative, the XMLDocument component also implements the IXMLDocument interface. This is a custom DOM-like API defined by Borland in the XMLIntf unit and comprising interfaces like IXMLNode, IXMLNodeList, and IXMLNodeCollection. This Borland interface simplifies some of the DOM operations by replacing multiple method calls, which are repeated often in sequence, with a single property or method.

In the following examples (particularly the DomCreate demo), I'll use both approaches to give you a better idea of the practical differences between the two approaches.

An XML Document in a TreeView

The starting point generally consists of loading a document from a file or creating it from a string, but you can also start with a new document. As a first example of using the DOM, I've built a program that can load an XML document into a DOM and show its structure in a TreeView control. I've also added to the XmlDomTree program a few buttons with sample code used to access to the elements of a sample file, as an example of accessing the DOM data. Loading the document is simple, but showing it in a tree requires a recursive function that navigates the nodes and subnodes. Here is the code for the two methods:

procedure TFormXmlTree.btnLoadClick(Sender: TObject); begin OpenDialog1.InitialDir := ExtractFilePath (Application.ExeName); if OpenDialog1.Execute then begin XMLDocument1.LoadFromFile(OpenDialog1.FileName); Treeview1.Items.Clear; DomToTree (XMLDocument1.DocumentElement, nil); TreeView1.FullExpand; end; end; procedure TFormXmlTree.DomToTree (XmlNode: IXMLNode; TreeNode: TTreeNode); var I: Integer; NewTreeNode: TTreeNode; NodeText: string; AttrNode: IXMLNode; begin // skip text nodes and other special cases if XmlNode.NodeType <> ntElement then Exit; // add the node itself NodeText := XmlNode.NodeName; if XmlNode.IsTextElement then NodeText := NodeText + ' = ' + XmlNode.NodeValue; NewTreeNode := TreeView1.Items.AddChild(TreeNode, NodeText); // add attributes for I := 0 to xmlNode.AttributeNodes.Count - 1 do begin AttrNode := xmlNode.AttributeNodes.Nodes[I]; TreeView1.Items.AddChild(NewTreeNode, '[' + AttrNode.NodeName + ' = "' + AttrNode.Text + '"]'); end; // add each child node if XmlNode.HasChildNodes then for I := 0 to xmlNode.ChildNodes.Count - 1 do DomToTree (xmlNode.ChildNodes.Nodes [I], NewTreeNode); end;

This code is interesting because it highlights some of the operations you can do with a DOM. First, each node has a NodeType property you can use to determine whether the node is an element, attribute, text node, or special entity (such as CDATA and others). Second, you cannot access the textual representation of the node (its NodeValue) unless it has a text element (notice that the text node will be skipped, as per the initial test). After displaying the name of the item, and then the text value if available, the program shows the content of each attribute directly and of each subnode by calling the DomToTree method recursively (see Figure 22.2).

Figure 22.2: The XmlDomTree example can open a generic XML document and show it inside a TreeView common control.

Once you have loaded the sample document that accompanies the XmlDomTree program (shown in Listing 22.1) into the XMLDocument component, you can use the various methods to access generic nodes, as in the previous tree-building code, or fetch specific elements. For example, you can grab the value of the attribute text of the root node by writing:

XMLDocument1.DocumentElement.Attributes ['text']

Notice that if there is no attribute called text, the call will fail with a generic error message, "Invalid variant type conversion," which helps neither you nor the end user to understand what's wrong. If you need to access to the first attribute of the root without knowing its name, you can use the following code:

XMLDocument1.DocumentElement.AttributeNodes.Nodes[0].NodeValue

To access the nodes, you use a similar technique, possibly taking advantage of the ChildValues array. This is a Delphi extension to the DOM, which allows you to pass as parameter either the name of the element or its numeric position:

XMLDocument1.DocumentElement.ChildNodes.Nodes[1].ChildValues['author']

This code gets the (first) author of the second book. You cannot use the ChildValues['book'] expression, because there are multiple nodes with the same name under the root node.

Listing 22.1: The Sample XML Document Used by Examples in this Chapter

Mastering Delphi 7 Cantu Delphi Developer's Handbook Cantu Gooch Delphi COM Programming Harmon Thinking in C++ Eckel Essential Pascal http://www.marcocantu.com Cantu Thinking in Java http://www.mindview.com Eckel

Creating Documents Using the DOM

Although I mentioned earlier that you can create an XML document by chaining together strings, this technique is far from robust. Using a DOM to create a document ensures that the XML will be well formed. Also, if the DOM has a schema definition attached, you can validate the structure of the document while adding data to it.

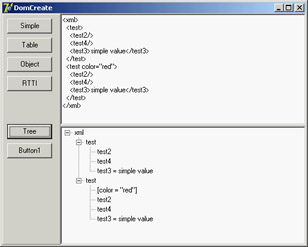

To highlight different cases of document creation, I've built the DomCreate example. This program can create XML documents within the DOM, showing their text on a memo and optionally in a TreeView.

| Warning |

The XMLDocument component uses the doAutoIndent option to improve the output of the XML text to the memo by formatting the XML in a slightly better way. You can choose the type of indentation by setting the NodeIndentStr property. To format generic XML text, you can also use the global FormatXMLData function using the default setting (two spaces) as indentation. Oddly, there doesn't seem a way to pass a different parameter to the function. |

The Simple button on the form creates simple XML text using the low-level, official DOM interfaces. The program calls the document's createElement method for each node, adding them as children of other nodes:

procedure TForm1.btnSimpleClick(Sender: TObject);

var

iXml: IDOMDocument;

iRoot, iNode, iNode2, iChild, iAttribute: IDOMNode;

begin

// empty the document

XMLDoc.Active := False;

XMLDoc.XML.Text := '';

XMLDoc.Active := True;

// root

iXml := XmlDoc.DOMDocument;

iRoot := iXml.appendChild (iXml.createElement ('xml'));

// node "test"

iNode := iRoot.appendChild (iXml.createElement ('test'));

iNode.appendChild (iXml.createElement ('test2'));

iChild := iNode.appendChild (iXml.createElement ('test3'));

iChild.appendChild (iXml.createTextNode('simple value'));

iNode.insertBefore (iXml.createElement ('test4'), iChild);

// node replication

iNode2 := iNode.cloneNode (True);

iRoot.appendChild (iNode2);

// add an attribute

iAttribute := iXml.createAttribute ('color');

iAttribute.nodeValue := 'red';

iNode2.attributes.setNamedItem (iAttribute);

// show XML in memo

Memo1.Lines.Text := FormatXMLData (XMLDoc.XML.Text);

end;

Notice that text nodes are added explicitly, attributes are created with a specific create call, and the code uses cloneNode to replicate an entire branch of the tree. Overall, the code is cumbersome to write, but after a while you may get used to this style. The effect of the program is shown (formatted in the memo and in the tree) in Figure 22.3.

Figure 22.3: The DomCreate example can generate various types of XML documents using a DOM.

The second example of DOM creation relates to a dataset. I've added to the form a dbExpress dataset component (but any other dataset would do). I also added to a button the call to my custom DataSetToDOM procedure, like this:

DataSetToDOM ('customers', 'customer', XMLDoc, SQLDataSet1);

The DataSetToDOM procedure creates a root node with the text of the first parameter, grabs each record of the dataset, defines a node with the second parameter, and adds a subnode for each field of the record, all using extremely generic code:

procedure DataSetToDOM (RootName, RecordName: string; XMLDoc: TXMLDocument; DataSet: TDataSet); var iNode, iChild: IXMLNode; i: Integer; begin DataSet.Open; DataSet.First; // root XMLDoc.DocumentElement := XMLDoc.CreateNode (RootName); // add table data while not DataSet.EOF do begin // add a node for each record iNode := XMLDoc.DocumentElement.AddChild (RecordName); for I := 0 to DataSet.FieldCount - 1 do begin // add an element for each field iChild := iNode.AddChild (DataSet.Fields[i].FieldName); iChild.Text := DataSet.Fields[i].AsString; end; DataSet.Next; end; DataSet.Close; end;

The preceding code uses the simplified DOM access interfaces provided by Borland, which include an AddChild node that creates the subnode, and the direct access to the Text property for defining a child node with textual content. This routine extracts an XML representation of your dataset, also opening up opportunities for web publishing, as I'll discuss later in the section on XSL.

Another interesting opportunity is the generation of XML documents describing Delphi objects. The DomCreate program has a button that describes a few properties of an object, again using the low-level DOM:

procedure AddAttr (iNode: IDOMNode; Name, Value: string);

var

iAttr: IDOMNode;

begin

iAttr := iNode.ownerDocument.createAttribute (name);

iAttr.nodeValue := Value;

iNode.attributes.setNamedItem (iAttr);

end;

procedure TForm1.btnObjectClick(Sender: TObject);

var

iXml: IDOMDocument;

iRoot: IDOMNode;

begin

// empty the document

XMLDoc.Active := False;

XMLDoc.XML.Text := '';

XMLDoc.Active := True;

// root

iXml := XmlDoc.DOMDocument;

iRoot := iXml.appendChild (iXml.createElement ('Button1'));

// a few properties as attributes (might also be nodes)

AddAttr (iRoot, 'Name', Button1.Name);

AddAttr (iRoot, 'Caption', Button1.Caption);

AddAttr (iRoot, 'Font.Name', Button1.Font.Name);

AddAttr (iRoot, 'Left', IntToStr (Button1.Left));

AddAttr (iRoot, 'Hint', Button1.Hint);

// show XML in memo

Memo1.Lines := XmlDoc.XML;

end;

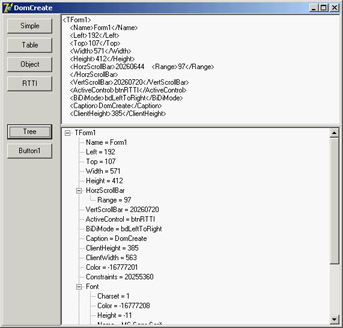

Of course, it is more interesting to have a generic technique capable of saving the properties of each Delphi component (or persistent object, to be more precise), recursing on persistent subobjects and indicating the names of referenced components. I've done this in the ComponentToDOM procedure, which uses the low-level RTTI information provided by the TypInfo unit, including the extraction of the list of component properties not having a default value. Once more, the program uses the simplified Delphi XML interfaces:

procedure ComponentToDOM (iNode: IXmlNode; Comp: TPersistent); var nProps, i: Integer; PropList: PPropList; Value: Variant; newNode: IXmlNode; begin // get list of properties nProps := GetTypeData (Comp.ClassInfo)^.PropCount; GetMem (PropList, nProps * SizeOf(Pointer)); try GetPropInfos (Comp.ClassInfo, PropList); for i := 0 to nProps - 1 do if not IsDefaultPropertyValue(Comp, PropList [i], nil) then begin Value := GetPropValue (Comp, PropList [i].Name); NewNode := iNode.AddChild(PropList [i].Name); NewNode.Text := Value; if (PropList [i].PropType^.Kind = tkClass) and (Value <> 0) then if TObject (Integer(Value)) is TComponent then NewNode.Text := TComponent (Integer(Value)).Name else // TPersistent but not TComponent: recurse ComponentToDOM (newNode, TObject (Integer(Value)) as TPersistent); end; finally FreeMem (PropList); end; end;

These two lines of code, in this case, trigger the creation of the XML document (shown in Figure 22.4):

Figure 22.4: The XML generated to describe the form of the DomCreate program. Notice (in the tree and in the memo text) that properties of class types are further expanded.

XMLDoc.DocumentElement := XMLDoc.CreateNode(Self.ClassName); ComponentToDOM (XMLDoc.DocumentElement, Self);

XML Data Binding Interfaces

You have seen that working with the DOM to access or generate a document is tedious, because you must use positional information and not logical access to the data. Also, handling series of repeated nodes of different possible types (as shown in the XML sample in Listing 22.1, describing books) is far from simple. Moreover, using a DOM, you can create any well-formed document; but (unless you use a validating DOM) you can add any subnode to any node, coming up with almost useless documents, because no one else will be able to manage them.

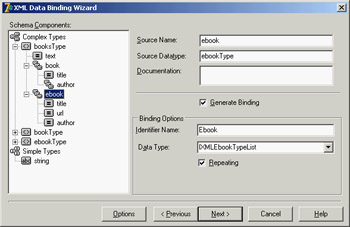

To solve these issues, Borland added to Delphi an XML Data Binding Wizard, which can examine an XML document or a document definition (a schema, a Document Type Definition (DTD), or another type of definition) and generate a set of interfaces for manipulating the document. These interfaces are specific to the document and its structure and allow you to have more readable code, but they are certainly less generic as far as the types of documents you can handle (and this is more positive than it might sound at first).

You can activate the XML Data Binding Wizard by using the corresponding icon in the first page of the IDE's New Items dialog box or by double-clicking the XMLDocument component. (It is odd that the corresponding command is not in the shortcut menu of the component.)

After a first page in which you can select an input file, this wizard shows you the structure of the document graphically, as you can see in Figure 22.5 for the sample XML file from Listing 22.1. In this page, you can give a name to each entity of the generated interfaces, if you don't like the defaults suggested by the wizard. You can also change the rules used by the wizard to generate the names (an extended flexibility I'd like to have in other areas of the Delphi IDE). The final page gives you a preview of the generated interfaces and offers options for generating schemas and other definition files.

Figure 22.5: Delphi's XML Data Binding Wizard can examine the structure of a document or a schema (or another document definition) to create a set of interfaces for simplified and direct access to the DOM data.

For the sample XML file with the author names, the XML Data Binding Wizard generates an interface for the root node, two interfaces for the elements lists of two different types of nodes (books and e-books), and two interfaces for the elements of the two types. Here are a few excerpts of the generated code, available in the XmlIntfDefinition unit of the XmlInterface example:

type

IXMLBooksType = interface(IXMLNode)

['{C9A9FB63-47ED-4F27-8ABA-E71F30BA7F11}']

{ Property Accessors }

function Get_Text: WideString;

function Get_Book: IXMLBookTypeList;

function Get_Ebook: IXMLEbookTypeList;

procedure Set_Text(Value: WideString);

{ Methods & Properties }

property Text: WideString read Get_Text write Set_Text;

property Book: IXMLBookTypeList read Get_Book;

property Ebook: IXMLEbookTypeList read Get_Ebook;

end;

IXMLBookTypeList = interface(IXMLNodeCollection)

['{3449E8C4-3222-47B8-B2B2-38EE504790B6}']

{ Methods & Properties }

function Add: IXMLBookType;

function Insert(const Index: Integer): IXMLBookType;

function Get_Item(Index: Integer): IXMLBookType;

property Items[Index: Integer]: IXMLBookType read Get_Item; default;

end;

IXMLBookType = interface(IXMLNode)

['{26BF5C51-9247-4D1A-8584-24AE68969935}']

{ Property Accessors }

function Get_Title: WideString;

function Get_Author: IXMLString_List;

procedure Set_Title(Value: WideString);

{ Methods & Properties }

property Title: WideString read Get_Title write Set_Title;

property Author: IXMLString_List read Get_Author;

end;

For each interface, the XML Data Binding Wizard also generates an implementation class that provides the code for the interface methods by translating the requests into DOM calls. The unit includes three initialization functions, which can return the interface of the root node from a document loaded in an XMLDocument component (or a component providing a generic IXMLDocument interface), or return one from a file, or create a brand new DOM:

function Getbooks(Doc: IXMLDocument): IXMLBooksType; function Loadbooks(const FileName: WideString): IXMLBooksType; function Newbooks: IXMLBooksType;

After generating these interfaces using the wizard in the XmlInterface example, I've repeated XML document access code that's similar to the XmlDomTree example but is much simpler to write (and to read). For example, you can get the attribute of the root node by writing

procedure TForm1.btnAttrClick(Sender: TObject); var Books: IXMLBooksType; begin Books := Getbooks (XmlDocument1); ShowMessage (Books.Text); end;

It is even simpler if you recall that while typing this code, Delphi's code insight can help by listing the available properties of each node, thanks to the fact that the parser can read in the interface definitions (although it cannot understand the format of a generic XML document). Accessing a node of one of the sublists is a matter of writing one of the following statements (possibly the second, with the default array property):

Books.Book.Items[1].Title // full Books.Book[1].Title // further simplified

You can use similarly simplified code to generate new documents or add new elements, thanks to the customized Add method available in each list-based interface. Again, if you don't have a predefined structure for the XML document, as in the dataset-based and RTTI-based examples of the previous demonstration, you won't be able to use this approach.

Validation and Schemas

The XML Data Binding Wizard can work from existing schemas or generate a schema for an XML document (and eventually save it in a file with the .XDB extension). An XML document describes some data, but to exchange this data among companies, it must stick to some agreed structure. A schema is a document definition against which a document can be checked for correctness, an operation usually indicated with the term validation.

The first—and still widespread—type of validation available for XML used document type definitions (DTDs). These documents describe the structure of the XML but cannot define the possible content of each node. Also, DTDs are not XML document themselves, but use a different, awkward notation.

At the end of 2000, the W3C approved the first official draft of XML schemas (already available in an incompatible version called XML-Data within Microsoft's DOM). An XML schema is an XML document that can validate both the structure of the XML tree and the content of the node. A schema is based on the use and definition of simple and complex data types, similar to what happens in an OOP language.

A schema defines complex types, indicating for each the possible nodes, their optional sequence (sequence, all), the number of occurrences of each subnode (minOccurs, maxOccurs), and the data type of each specific element. Here is the schema defined by the XML Data Binding Wizard for the sample books file:

Microsoft and Apache DOM engines have good support for schemas. Another tool I've used for validation is XML Schema Validator (XSV), an open-source attempt at a conformant schema-aware processor, which can be used either directly via the Web or after downloading a command-line executable (see the links to the current website of this tool in the W3C's XML Schema pages).

| Note |

The Delphi editor supports code completion for XML files via DTDs. Dropping a DTD file in Delphi's bin directory and referring to it with a DOCTYPE tag should enable this feature, which is not officially supported by Borland. |

Using the SAX API

The Simple API for XML (SAX) doesn't create a tree for the XML nodes, but parses the node—firing events for each node, attribute, value, and so on. Because it doesn't keep the document in memory, using the SAX allows you to manage much larger documents. Its approach is also useful for one-time examination of a document or retrieval of specific information. This is a list of the most important events fired by the SAX:

- StartDocument and EndDocument for the entire document

- StartElement and EndElement for each node

- Characters for the text within the nodes

It is common to use a stack to handle the current path within the nodes tree, and push and pop elements to and from the stack for every StartElement and EndElement event.

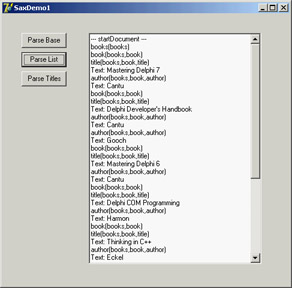

Delphi does not include specific support for the SAX interface, but you can import Microsoft's XML support (the MSXML library). In particular, for the SaxDemo1 example I've used version 2 of MSXML, because this version is widely available. I've generated a Pascal type library import unit from the type library, and the import unit is available within the source code of the program, but you must have that specific COM library registered on your computer to run the program successfully.

| Note |

Another example at the end of this chapter (LargeXml) demonstrates, among other things, the use of the SAX API, including the OpenXml engine. |

To use the SAX, you must install a SAX event handler within a SAX reader, and then load a file and parse it. I've used the SAX reader interface provided by MSXML for VB programmers. The official (C++) interface had a few errors in its type library that prevented Delphi from importing it properly. The main form of the SaxDemo1 example declares

sax: IVBSAXXMLReader;

In the FormCreate method, the sax variable is initialized with the COM object:

sax := CoSAXXMLReader.Create; sax.ErrorHandler := TMySaxErrorHandler.Create;

The code also sets an error handler, which is a class implementing a specific interface (IVBSAXErrorHandler) with three methods that are called depending on the severity of the problem: error, fatalError, and ignorableWarning.

Simplifying the code a little, the SAX parser is activated by calling the parseURL method after assigning a content handler to it:

sax.ContentHandler := TMySaxHandler.Create; sax.parseURL (filename)

So, the code ultimately resides in the TMySaxHandler class, which has the SAX events. Because I have multiple SAX content handlers in this example, I've written a base class with the core code and a few specialized versions for specific processing. Following is the code of the base class, which implements both the IVBSAXContentHandler interface and the IDispatch interface the IVBSAXContentHandler interface is based on:

type TMySaxHandler = class (TInterfacedObject, IVBSAXContentHandler) protected stack: TStringList; public constructor Create; destructor Destroy; override; // IDispatch function GetTypeInfoCount(out Count: Integer): HResult; stdcall; function GetTypeInfo(Index, LocaleID: Integer; out TypeInfo): HResult; stdcall; function GetIDsOfNames(const IID: TGUID; Names: Pointer; NameCount, LocaleID: Integer; DispIDs: Pointer): HResult; stdcall; function Invoke(DispID: Integer; const IID: TGUID; LocaleID: Integer; Flags: Word; var Params; VarResult, ExcepInfo, ArgErr: Pointer): HResult; stdcall; // IVBSAXContentHandler procedure Set_documentLocator(const Param1: IVBSAXLocator); virtual; safecall; procedure startDocument; virtual; safecall; procedure endDocument; virtual; safecall; procedure startPrefixMapping(var strPrefix: WideString; var strURI: WideString); virtual; safecall; procedure endPrefixMapping(var strPrefix: WideString); virtual; safecall; procedure startElement(var strNamespaceURI: WideString; var strLocalName: WideString; var strQName: WideString; const oAttributes: IVBSAXAttributes); virtual; safecall; procedure endElement(var strNamespaceURI: WideString; var strLocalName: WideString; var strQName: WideString); virtual; safecall; procedure characters(var strChars: WideString); virtual; safecall; procedure ignorableWhitespace(var strChars: WideString); virtual; safecall; procedure processingInstruction(var strTarget: WideString; var strData: WideString); virtual; safecall; procedure skippedEntity(var strName: WideString); virtual; safecall; end;

The most interesting portion, of course, is the final list of SAX events. All this base class does is emit information to a log when the parser starts (startDocument) and finishes (endDocument) and keep track of the current node and its parent nodes with a stack:

// TMySaxHandler.startElement stack.Add (strLocalName); // TMySaxHandler.endElement stack.Delete (stack.Count - 1);

An implementation is provided by the TMySimpleSaxHandler class, which overrides the startElement event triggered for any new node to output the current position in the tree with the following statement:

Log.Add (strLocalName + '(' + stack.CommaText + ')');

The second method of the class is the characters event, which is triggered when a node value (or a test node) is encountered and outputs its content (as you can see in Figure 22.6):

procedure TMySimpleSaxHandler.characters(var strChars: WideString);

var

str: WideString;

begin

inherited;

str := RemoveWhites (strChars);

if (str <> '') then

Log.Add ('Text: ' + str);

end;

Figure 22.6: The log produced by reading an XML document with the SAX in the Sax-Demo1 example

This is a generic parsing operation affecting the entire XML file. The second derived SAX content handler class refers to the specific structure of the XML document, extracting only nodes of a given type. In particular, the program looks for nodes of the title type. When a node has this type (in startElement), the class sets the isbook Boolean variable. The text value of the node is considered only immediately after a node of this type is encountered:

procedure TMyBooksListSaxHandler.startElement(var strNamespaceURI, strLocalName, strQName: WideString; const oAttributes: IVBSAXAttributes); begin inherited; isbook := (strLocalName = 'title'); end; procedure TMyBooksListSaxHandler.characters(var strChars: WideString); var str: string; begin inherited; if isbook then begin str := RemoveWhites (strChars); if (str <> '') then Log.Add (stack.CommaText + ': ' + str); end; end;

Mapping XML with Transformations

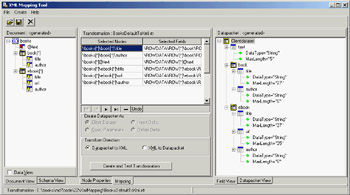

You can use one more technique in Delphi to handle some XML documents: You can create a transformation to translate the XML of a generic document into the format used natively by the ClientDataSet component when saving data to a MyBase XML file. In the reverse direction, another transformation can turn a dataset available within a ClientDataSet (through a DataSetProvider component) into an XML file of a required format (or schema).

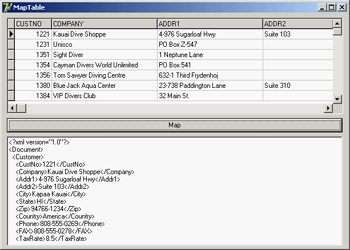

Delphi includes a wizard to generate such transformations. Called the XML Mapping Tool, or XML Mapper for short, it can be invoked from the IDE's Tools menu or executed as a stand-alone application. The XML Mapper, shown in Figure 22.7, is a design-time helper that assists you in defining transformation rules between the nodes of a generic XML document and fields of the ClientDataSet data packet.

Figure 22.7: The XML Mapper shows the two sides of a transformation to define a mapping between them (with the rules indicated in the central portion).

The XML Mapper window has three areas:

- On the left is the XML document section, which displays information about the structure of the XML document (and eventually its data, if the related check box is active) in the Document View or an XML schema in the Schema View, depending on the selected tab.

- On the right is the data packet section, which displays information about the metadata in the data packet, either in the Field View (indicating the dataset structure) or in the Datapacket View (reporting the XML structure). The XML Mapper can also open files in the native ClientDataSet format.

- The central portion is used by the mapping section. It contains two pages: Mapping, where you can see the correspondence between selected elements of the two sides that will be part of the mapping; and Node Properties, where you can modify the data types and other details of each possible mapping.

The Mapping page of the central pane also hosts the shortcut menu used to generate the transformation. The other panes and views have specific shortcut menus you can use to perform the various actions (besides the few commands in the main menu).

You can use XML Mapper to map an existing schema (or extract it from a document) to a new data packet, an existing data packet to a new schema or document, or an existing data packet into an existing XML document (if a match is reasonable). In addition to converting the data of an XML file into a data packet, you can also convert to a delta packet of the ClientDataSet. This technique is useful for merging a document to an existing table, as if a user had inserted the modified table records. In particular, you can transform an XML document into a delta packet for records to be modified, deleted, or inserted.

The result of using the XML Mapper is one or more transformation files, each representing a one-way conversion (so you need at least two transformation files to convert data back and forth). These transformation files are then used at design time and at run time by the XMLTransform, XMLTransformProvider, and XMLTransformClient components.

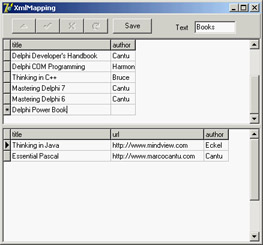

As an example, I opened the books XML document, which has a structure that doesn't easily match a table, because it includes two lists of values of different types (I've skipped easier examples in which the XML has a plain rectangular structure). After opening the Sample.XML file in the XML Document section, I used its shortcut menu to select all of its elements (Select All) and to create the data packet (Create Datapacket From XML). This command automatically fills the right pane with the data packet and the central portion with the proposed transformation. You can also view its effect in a sample program by clicking the Create And Test Transformation button. Doing so opens a generic application that can load a document into the dataset using the transformation you've just created.

In this case, the XML Mapper generates a table with two dataset fields: one for each possible list of subelements. This was the only possible standard solution, because the two sublists have different structures, and it is the only solution that allows you to edit the data in a DBGrid attached to the ClientDataSet and save it back to a complete XML file, as demonstrated by the XmlMapping example. This program is basically a Windows-based editor for a complex XML document.

The example uses a TransformProvider component with two transformation files attached to read in an XML document and make it available to a ClientDataSet. As the name suggests, this component is a dataset provider. To build the user interface, I didn't connect the ClientDataSet directly to a grid, because it has a single record with a text field plus two detailed datasets. For this reason, I added to the program two more ClientDataSet components attached to the dataset fields and connected to two DBGrid controls. This explanation is easier to understand by looking at the definition of the non-visual components from DFM source code in the following excerpt and at its output in Figure 22.8.

Figure 22.8: The XmlMapping example uses a TransformProvider component to make a complex XML document available for editing within multiple ClientData-Set components.

object XMLTransformProvider1: TXMLTransformProvider TransformRead.TransformationFile = 'BooksDefault.xtr' TransformWrite.TransformationFile = 'BooksDefaultToXml.xtr' XMLDataFile = 'Sample.xml' end object ClientDataSet1: TClientDataSet ProviderName = 'XMLTransformProvider1' object ClientDataSet1text: TStringField object ClientDataSet1book: TDataSetField object ClientDataSet1ebook: TDataSetField end object ClientDataSet2: TClientDataSet DataSetField = ClientDataSet1book end object ClientDataSet3: TClientDataSet DataSetField = ClientDataSet1ebook end

This program allows you to edit the data of the various sublists of nodes within the grids, modifying them and also adding or deleting records. As you apply the changes to the dataset (clicking the Save button, which calls ApplyUdpates), the transform provider saves an updated version of the file to disk.

As an alternative approach, you can also create transformations that map only portions of the XML document into a dataset. As an example, see the BooksOnly.xtr file in the folder of the XmlMapping example. The modified XML document you'll generate will have a different structure and content from the original, including only the portion you've selected. So, it can be useful for viewing the data, but not for editing it.

| Note |

It is not surprising that the transformation files are themselves XML documents, as you can see by opening one in the editor. This XML document uses a custom format. |

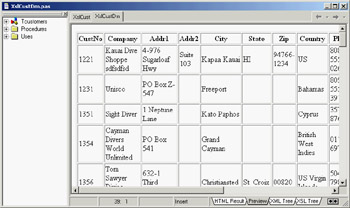

At the opposite side, you can see how a transformation can be used to take a database table or the result of a query and produce an XML file with a more readable format than that provided by default by the ClientDataSet persistence mechanism. To build the MapTable example, I placed a dbExpress SimpleDataSet component on a form and attached a DataSetProvider to it and a ClientDataSet to the provider. After opening the table and the client dataset, I saved its content to an XML file.

At that point, I opened the XML Mapper, loaded the data packet file into it, selected all the data packet nodes (with the Select All command from the shortcut menu) and invoked the Create XML From Datapacket command. In the following dialog box, I accepted the default name mappings for fields and only changed the suggested name for record nodes (ROW) into something more readable (Customer). If you now test the transformation, the XML Mapper will display the contents of the resulting XML document in a custom tree view.

After saving the transformation file, I was ready to resume developing the program, removing the ClientDataSet and adding a DataSource and a DBGrid (as a user might edit in on an attached DBGrid before transforming it), and an XMLTransformClient component. This component has the transformation file connected to it, but not an XML file. Instead, it refers to the data through the provider. Clicking the button shows the XML document within a memo (after formatting it) instead of saving it to a file, something you can do by calling the GetDataAsXml method (even if the Help file is far from clear about the use of this method):

procedure TForm1.btnMapClick(Sender: TObject);

begin

Memo1.Lines.Text := FormatXmlData(XMLTransformClient1.GetDataAsXml(''));

end;

This is the only code for the program visible at run time in Figure 22.9; you can see the original dataset in the DBGrid and the resulting XML document in the memo control below the grid. The application has much simpler code than the DomCreate example I used to generate a similar XML document, but it requires the design-time definition of the transformation. The DomCreate example could work on any dataset at run time without any connection to a specific table, because it has rather generic code. In theory, it is possible to produce similar dynamic mappings by using the events of the generic XMLTransform component, but I find it easier to use the DOM-based approach discussed earlier. Notice also that the FormatXmlData call produces nicer output but slows down the program, because it involves loading the XML into a DOM.

Figure 22.9: The MapTable example generates an XML document from a database table using a custom transformation file.

XML and Internet Express

Once you have defined the structure of an XML document, you might want to let users see and edit the data in a Windows application or over the Web. This second case is interesting because Delphi provides specific support for it. Delphi 5 introduced an architecture called Internet Express, which is now available as part of the WebSnap platform. WebSnap also offers support for XSL, which I'll discuss later in this chapter.

In Chapter 16, "Multitier DataSnap Applications," I discussed the development of DataSnap applications. Internet Express provides a client component called XMLBroker for this architecture, which can be used in place of a client dataset to retrieve data from a middle-tier DataSnap program and make it available to a specific type of page producer called InetXPageProducer. You can use these components in a standard WebBroker application or in a WebSnap program. The idea behind Internet Express is that you write a web server extension (as discussed in Chapter 20, "Web Programming with WebBroker and WebSnap"), which in turn produces web pages hooked to your DataSnap server. Your custom application acts as a DataSnap client and produces pages for a browser client. Internet Express offers the services required to build this custom application easily.

I know this sounds confusing, but Internet Express is a four-tier architecture: SQL server, application server (the DataSnap server), web server with a custom application, and web browser. Of course, you can place the database access components within the same application handling the HTTP request and generating the resulting HTML, as in a client/ server solution. You can even access a local database or an XML file, in a two-tier structure (the server program and the browser).

In other words, Internet Express is a technology for building clients based on a browser, which lets you send the entire dataset to the client computer along with the HTML and some JavaScript for manipulating the XML and showing it into the user interface defined by the HTML. The JavaScript enables the browser to show the data and manipulate it.

The XMLBroker Component

Internet Express uses multiple technologies to accomplish this result. The DataSnap data packets are converted into the XML format to let the program embed this data into the HTML page for web client-side manipulation. The delta data packet is also represented in XML. These operations are performed by the XMLBroker component, which can handle XML and provide data to the new JavaScript components. Like the ClientDataSet, the XMLBroker has the following:

- A MaxRecords property indicating the number of records to add to a single page

- A Params property hosting the parameters that components will forward to the remote query through the provider

- A WebDispatch property indicating the update request the broker responds to

The InetXPageProducer allows you to generate HTML forms from datasets in a visual way similar to the development of an AdapterPageProducer user interface. The Internet Express architecture, the interfaces it uses internally, and some of its IDE editor can together be considered the parent of the WebSnap architecture. With the notable difference of generating scripts to be executed on the server side and on the client side, they both provide an editor for placing visual components and generating such scripts. Personally, I'm not terribly happy that the older Internet Express is more XML-oriented than the newer WebSnap.

| Tip |

Another common feature of the InetXPageProducer and the AdapterPageProducer is the support for Cascading Style Sheets (CSS). These components have the Style and StylesFile properties for defining the CSS, and each visual element has a StyleRule property you can use to select the style name. |

JavaScript Support

To make the editing operations on the client side powerful, the InetXPageProducer uses special JavaScript components and code. Delphi embeds a large JavaScript library, which the browser must download. This process might seem a nuisance, but it is the only way the browser interface (which is based on dynamic HTML) can be rich enough to support field constraints and other business rules with the browser. This functionality is impossible with plain HTML. The JavaScript files provided by Borland, which you should make available on the website hosting the application, are the following:

|

File |

Description |

|---|---|

|

Xmldom.js |

DOM-compatible XML parser (for browsers lacking native XML DOM support) |

|

Xmldb.js |

JavaScript classes for the HTML controls |

|

Xmldisp.js |

JavaScript classes for binding XML data with the HTML controls |

|

Xmlerrdisp.js |

Classes for reconciling errors |

|

XmlShow.js |

JavaScript functions to display data and delta packets (for debugging purposes) |

HTML pages generated by Internet Express usually include references to these JavaScript files, such as:

You can customize the JavaScript by adding code directly to the HTML pages or by creating new Delphi components written to fit with the Internet Express architecture that emits JavaScript code (possibly along with HTML). As an example, the sample TPromptQueryButton class of INetXCustom generates the following HTML and JavaScript code:

<script language=javascript type="text/javascript">

function PromptSetField(input, msg) {

var v = prompt(msg);

if (v == null || v == "")

return false;

input.value = v

return true;

}

var QueryForm3 = document.forms['QueryForm3'];

script>

<input type=button value="Prompt..."

onclick="if (PromptSetField(PromptResult, 'Enter some text

'))

QueryForm3.submit();">

| Tip |

If you plan to use Internet Express, look at the INetXCustom extra demo components, available in the DemosMidasInternetExpress INetXCustom folder. Follow the detailed instructions in the readme.txt file to install these components, which are provided by Borland with no support but allow you to add many more features to your Internet Express applications with little extra effort. |

To deploy this architecture you don't need anything special on the client side, because any browser up to the HTML 4 standard can be used, on any operating system. The web server, however, must be a Win32 server (this technology is not available in Kylix), and you must deploy the DataSnap libraries on it.

Building an Example

To better understand what I'm talking about, and as a way to cover more technical details, let's try a demo called IeFirst. To avoid configuration issues, this is a CGI application accessing a dataset directly—in this case, a local table retrieved via a ClientDataSet component. Later, I'll show you how to turn an existing DataSnap Windows client into a browser-based interface. To build IeFirst, I created a new CGI application and added to its data module a ClientDataSet component hooked to a local .CDS file and a DataSetProvider component connected with the dataset. The next step is to add an XMLBroker component and connect it to the provider:

object ClientDataSet1: TClientDataSet FileName = 'C:Program FilesCommon FilesBorland SharedDataemployee.cds' end object DataSetProvider1: TDataSetProvider DataSet = ClientDataSet1 end object XMLBroker1: TXMLBroker ProviderName = 'DataSetProvider1' WebDispatch.MethodType = mtAny WebDispatch.PathInfo = 'XMLBroker1' ReconcileProducer = PageProducer1 OnGetResponse = XMLBroker1GetResponse end

The ReconcileProducer property is required to show a proper error message in case of an update conflict. As you'll see later, one of the Delphi demos includes some custom code, but in this example I've connected a traditional PageProducer component with a generic HTML error message. After setting up the XML broker, you can add an InetXPageProducer to the web data module. This component has a standard HTML skeleton; I've customized it to add a title, without touching the special tags:

IeFirst

Internet Express First Demo (IeFirst.exe)

<#INCLUDES><#STYLES><#WARNINGS><#FORMS><#SCRIPT>

The special tags are automatically expanded using the JavaScript files of the directory specified by the IncludePathURL property. You must set this property to refer to the web server directory where these files reside. You can find them in the Delphi7SourceWebMidas directory. The five tags have the following effect:

|

Tag |

Effect |

|---|---|

|

<#INCLUDES> |

Generates the instructions to include the JavaScript libraries |

|

<#STYLES> |

Adds the embedded style sheet definition |

|

<#WARNINGS> |

Used at design time to show errors in the InetXPageProducer editor |

|

<#FORMS> |

Generates the HTML code produced by the components of the web page |

|

<#SCRIPT> |

Adds a JavaScript block used to start the client-side script |

| Note |

The InetXPageProducer component also handles a few more internal tags. <#BODYELEMENTS> corresponds to all five tags of the predefined template. <#COMPONENT Name=WebComponentName> is part of the generated HTML code used to declare the components generated visually. <#DATAPACKET XMLBroker=BrokerName> is replaced with the XML of the data packet. |

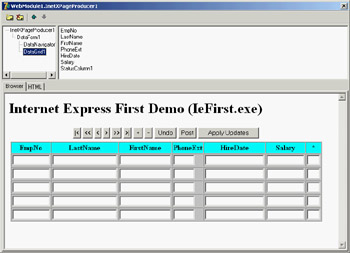

To customize the resulting HTML of the InetXPageProducer, you can use its editor, which again is similar to the one for WebSnap server-side scripting. Double-click the InetXPageProducer component, and Delphi opens a window like the one shown in Figure 22.10 (with the example's final settings). In this editor, you can create complex structures starting with a query form, data form, or generic layout group. In the example data form, I added a DataGrid and a DataNavigator component without customizing them any further (an operation you do by adding child buttons, columns, and other objects, which fully replace the defaults).

Figure 22.10: The InetXPage-Producer editor allows you to build complex HTML forms visually, similarly to the AdapterPageProducer.

The DFM code for the InetXPageProducer and its internal components in my example is as follows. You can see the core settings plus some limited graphical customizations:

object InetXPageProducer1: TInetXPageProducer IncludePathURL = '/jssource/' HTMLDoc.Strings = (...) object DataForm1: TDataForm object DataNavigator1: TDataNavigator XMLComponent = DataGrid1 Custom = 'align="center"' end object DataGrid1: TDataGrid XMLBroker = XMLBroker1 DisplayRows = 5 TableAttributes.BgColor = 'Silver' TableAttributes.CellSpacing = 0 TableAttributes.CellPadding = 2 HeadingAttributes.BgColor = 'Aqua' object EmpNo: TTextColumn... object LastName: TTextColumn... object FirstName: TTextColumn... object PhoneExt: TTextColumn... object HireDate: TTextColumn... object Salary: TTextColumn... object StatusColumn1: TStatusColumn... end end end

The value of these components is in the HTML (and JavaScript) code they generate, which you can preview by selecting the HTML tab of the InetXPageProducer editor. Here are a few pieces of the definitions in the HTML, for the buttons, the data grid heading, and one of the grid's cells:

// buttons

Figure 22.12: The result of an XSLT transformation generated (even at design time) by the XSLPageProducer component in the XslCust example

| Note |

The standard XSL template has been extended since Delphi 6, because the original versions didn't account for null fields omitted from the XML data packet. I presented several extensions to the original XSL code at the 2002 Borland Conference, and some of my suggestions have been incorporated in the template. |

This code generates an HTML table consisting of the expansion of field metadata and row data. The fields are used to generate the table heading, with a cell for each entry in a single row. The row data is used to fill in the other rows of the table. Taking the value of each attribute (select="@*") wouldn't be enough, because an attribute might be missing. For this reason, the list of fields and the current row are saved in two variables; then, for each field, the XSL code extracts the value of a row item having an attribute name (@*[name()=...) corresponding to the name of the current field stored in its attrname attribute (@attrname). This code is far from simple, but it is a compact and portable way to examine different portions of an XML document at the same time.

Direct XSL Transformations with the DOM

Using the XSLPageProducer can be handy, but generating multiple pages based on the same data just to handle different possible XSL styles with WebSnap isn't the best approach. I've built a plain CGI application called CdsXslt that can transform a ClientDataSet data packet into different types of HTML, depending on the name of the XSL file passed as a parameter. The advantage is that I can modify the existing XSL files and add new XSL files to the system without having to recompile the program.

To obtain the XSL transformation, the program loads both the XML and the XSL files into two XMLDocument components called xmlDom and XslDom. Then it invokes the transformNode method of the XML document, passing the XSL document as a parameter and filling in a third XMLDocument component called HtmlDom:

procedure TWebModule1.WebModule1WebActionItem1Action(Sender: TObject;

Request: TWebRequest; Response: TWebResponse; var Handled: Boolean);

var

xslfile, xslfolder: string;

attr: IDOMAttr;

begin

// open the client dataset and load its XML in a DOM

ClientDataSet1.Open;

XmlDom.Xml.Text := ClientDataSet1.XMLData;

XmlDom.Active := True;

// load the requested xsl file

xslfile := Request.QueryFields.Values ['style'];

if xslfile = '' then

xslfile := 'customer.xsl';

xslfolder := ExtractFilePath (ParamStr (0)) + 'xsl';

if FileExists (xslfolder + xslfile) then

xslDom.LoadFromFile (xslfolder + xslfile)

else

raise Exception.Create('Missing file: ' + xslfolder + xslfile);

XSLDom.Active := True;

if xslfile = 'single.xsl' then

begin

attr := xslDom.DOMDocument.createAttribute('select');

attr.value := '//ROW[@CustNo="' + Request.QueryFields.Values ['id'] + '"]';

xslDom.DOMDocument.getElementsByTagName ('xsl:apply-templates').

item[0].attributes.setNamedItem(attr);

end;

// do the transformation

HTMLDom.Active := True;

xmlDom.DocumentElement.transformNode (xslDom.DocumentElement, HTMLDom);

Response.Content := HTMLDom.XML.Text;

end;

The code uses the DOM to modify the XSL document for displaying a single record, adding the XPath statement for selecting the record indicated by the id query field. This id is added to the hyperlink by the XSL with the list of records, but I'll skip listing more XSL files. They are available for study in the XSL subfolder of this example's folder.

| Warning |

To run this program, deploy the XSL files in a folder called XSL under the one where the script is located. You can find the demo files in the XSL subfolder of the scripts folder of this chapter. To deploy these files in a different location, change the code above that extracts the XSL folder name from the program name available in the first common line parameter (as the global Application object defined in the Forms unit is not accessible in a CGI application). |

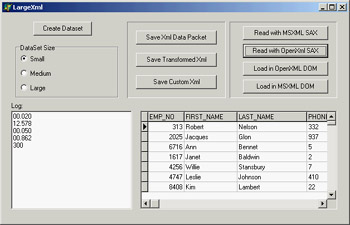

Processing Large XML Documents

As you have seen, there are often many different techniques to accomplish the same task with XML. In many cases you can choose any solution with the goal of writing less and more maintainable code; but when you need to process a large number of XML documents or very large XML documents, you must consider efficiency.

Discussing theory by itself is not terribly useful, so I've built an example you can use (and modify) to test different solutions. The example is called LargeXml, and it covers a specific area: moving data from a database to an XML file and back. The example can open a dataset (using dbExpress) and then replicate the data many times in a ClientDataSet in memory. The structure of the in-memory ClientDataSet is cloned from that of the data access component:

SimpleDataSet1.Open; ClientDataSet1.FieldDefs := SimpleDataSet1.FieldDefs; ClientDataSet1.CreateDataSet;

After using a radio group to determine the amount of data you want to process (some options require minutes on a slow computer), the data is cloned with this code:

while ClientDataSet1.RecordCount < nCount do begin SimpleDataSet1.RecNo := Random (SimpleDataSet1.RecordCount) + 1; ClientDataSet1.Insert; ClientDataSet1.Fields [0].AsInteger := Random (10000); for I := 1 to SimpleDataSet1.FieldCount - 1 do ClientDataSet1.Fields [i].AsString := SimpleDataSet1.Fields [i].AsString; ClientDataSet1.Post; end;

From a ClientDataSet to an XML Document

Now that the program has a (large) dataset in memory, it provides three different ways to save the dataset to a file. The first is to save the XMLData of the ClientDataSet directly to a file, obtaining an attribute-based document. This is probably not the format you want, so the second solution is to apply an XmlMapper transformation with an XMLTransformClient component. The third solution involves processing the dataset directly and writing out each record to a file:

procedure TForm1.btnSaveCustomClick(Sender: TObject);

var

str: TFileStream;

s: string;

i: Integer;

begin

str := TFileStream.Create ('data3.xml', fmCreate);

try

ClientDataSet1.First;

s := '';

str.Write(s[1], Length (s));

while not ClientDataSet1.EOF do

begin

s := '';

for i := 0 to ClientDataSet1.FieldCount - 1 do

s := s + MakeXmlstr (ClientDataSet1.Fields[i].FieldName,

ClientDataSet1.Fields[i].AsString);

s := MakeXmlStr ('employeeData', s);

str.Write(s[1], length (s));

ClientDataSet1.Next

end;

s := '';

str.Write(s[1], length (s));

finally

str.Free;

end;

end;

This code uses a simple (but effective) support function to create XML nodes:

function MakeXmlstr (node, value: string): string; begin Result := '<' + node + '>' + value + ''; end;

If you run the program, you can see the time taken by each operation, as shown in Figure 22.13. Saving the ClientDataSet data is the fastest approach, but you probably don't get the result you want. Custom streaming is only slightly slower; but you should consider that this code doesn't require you to first move the data to a ClientDataSet, because you can apply it directly even to a unidirectional dbExpress dataset. You should forget using the code based on the XmlMapper for a large dataset, because it is hundreds of times slower, even for a small dataset (I haven't been able to try a large dataset, because the process takes too long). For example, the 50 milliseconds required by custom streaming for a small dataset become more than 10 seconds when I use the mapping, and the result is very similar.

Figure 22.13: The LargeXml example in action

From an XML Document to a ClientDataSet

Once you have a large XML document, obtained by a program (as in this case) or from an external source, you need to process it. As you have seen, XmlMapper support is far too slow, so you are left with three alternatives: an XSL transformation, a SAX, or a DOM. XSL trans-formations will probably be fast enough, but in this example I've opened the document with a SAX; it's the fastest approach and doesn't require much code. The program can also load a document in a DOM, but I haven't written the code to navigate the DOM and save the data back to a ClientDataSet.

In both cases, I've tested the OpenXml engine versus the MSXML DOM. This allows you to see the two SAX solutions compared, because (unluckily) the code is slightly different. I can summarize the results here: Using the MSXML SAX is slightly faster than using the OpenXml SAX (the difference is about 20 percent), whereas loading in the DOM marks a large advantage in favor of MSXML.

The MSXML SAX code uses the same architecture discussed in the SaxDemo1 example, so here I've listed only the code of the handlers you use. As you can see, at the beginning of an employeeData element you insert a new record, which is posted when the same node is closed. Lower-level nodes are added as fields of the current record. Here is the code:

procedure TMyDataSaxHandler.startElement(var strNamespaceURI, strLocalName, strQName: WideString; const oAttributes: IVBSAXAttributes); begin inherited; if strLocalName = 'employeeData' then Form1.clientdataset2.Insert; strCurrent := ''; end; procedure TMyDataSaxHandler.characters(var strChars: WideString); begin inherited; strCurrent := strCurrent + RemoveWhites(strChars); end; procedure TMyDataSaxHandler.endElement(var strNamespaceURI, strLocalName, strQName: WideString); begin if strLocalName = 'employeeData' then Form1.clientdataset2.Post; if stack.Count > 2 then Form1.ClientDataSet2.FieldByName (strLocalName).AsString := strCurrent; inherited; end;

The code for the event handlers in the OpenXml version is similar. All that changes are the interface of the methods and the names of the parameters:

type TDataSaxHandler = class (TXmlStandardHandler) protected stack: TStringList; strCurrent: string; public constructor Create(aowner: TComponent); override; function endElement(const sender: TXmlCustomProcessorAgent; const locator: TdomStandardLocator; namespaceURI, tagName: wideString): TXmlParserError; override; function PCDATA(const sender: TXmlCustomProcessorAgent; const locator: TdomStandardLocator; data: wideString): TXmlParserError; override; function startElement(const sender: TXmlCustomProcessorAgent; const locator: TdomStandardLocator; namespaceURI, tagName: wideString; attributes: TdomNameValueList): TXmlParserError; override; destructor Destroy; override; end;

It is also more difficult to invoke the SAX engine, as shown in the following code (from which I've removed the code for the creation of the dataset, the timing, and the logging):

procedure TForm1.btnReadSaxOpenClick(Sender: TObject); var agent: TXmlStandardProcessorAgent; reader: TXmlStandardDocReader; filename: string; begin Log := memoLog.Lines; filename := ExtractFilePath (Application.Exename) + 'data3.xml'; agent := TXmlStandardProcessorAgent.Create(nil); reader:= TXmlStandardDocReader.Create (nil); try reader.NextHandler := TDataSaxHandler.Create (nil); // our custom class agent.reader := reader; agent.processFile(filename, filename); finally agent.free; reader.free; end; end;

What s Next?

In this chapter I've covered XML and related technologies, including DOM, SAX, XSLT, XML schemas, XPath, and a few more. You've seen how Delphi simplifies DOM programming with XML access using interfaces and XML transformations. I've also discussed the use of XSL for web programming, introducing the XSLT support of WebSnap and the Internet Express architecture.

Chapter 23 will continue the discussion of XML with one of the most interesting and promising technologies of the last few years: web services. I'll cover SOAP and WSDL, and also introduce UDDI and other related technologies. If you are interested in the topics discussed here from the Delphi perspective, you should refer to books specifically devoted to XML, XML schemas, and XSLT.

Part I - Foundations

- Delphi 7 and Its IDE

- The Delphi Programming Language

- The Run-Time Library

- Core Library Classes

- Visual Controls

- Building the User Interface

- Working with Forms

Part II - Delphi Object-Oriented Architectures

- The Architecture of Delphi Applications

- Writing Delphi Components

- Libraries and Packages

- Modeling and OOP Programming (with ModelMaker)

- From COM to COM+

Part III - Delphi Database-Oriented Architectures

- Delphis Database Architecture

- Client/Server with dbExpress

- Working with ADO

- Multitier DataSnap Applications

- Writing Database Components

- Reporting with Rave

Part IV - Delphi, the Internet, and a .NET Preview

- Internet Programming: Sockets and Indy

- Web Programming with WebBroker and WebSnap

- Web Programming with IntraWeb

- Using XML Technologies

- Web Services and SOAP

- The Microsoft .NET Architecture from the Delphi Perspective

- Delphi for .NET Preview: The Language and the RTL

- Appendix A Extra Delphi Tools by the Author

- Appendix B Extra Delphi Tools from Other Sources

- Appendix C Free Companion Books on Delphi

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 279