Designing World-Class Services (Design for Lean Six Sigma)

Overview

By Kimberly Watson-Hemphill (George Group)[1] and Rod Skewes (Caterpillar, Inc.)[2]

In the summer of 2001, an employee from Caterpillar’s Malaga, Spain, facility was trying to book into a hotel in

Peoria, Illinois, but his corporate credit card wasn’t accepted. The employee called the Corporate Travel office in Peoria thinking they might be able to help, but no one there knew anything about his credit card. Corporate Travel called Corporate Treasury, but they didn’t know anything about it either.

Eventually everything was straightened out, but this one incident set off a chain reaction once the corporate departments realized that it was the very small tip of a very large iceberg:

- There were a number of credit card programs that existed at each of Cat’s global sites

- These programs weren’t connected in any way

- There was no way of knowing how many credit cards they had, how much was spent on those cards, or the rebate dollars (financial incentives), if any, that the company was getting from the overall program

That meant Caterpillar would have to invent a process if it wanted to be able to manage its corporate credit card program.

The DMAIC model illustrated by cases studies from previous chapters works great if you’re trying to improve processes, services, or products that already exist. But the basic DMAIC toolkit used by many organizations doesn’t incorporate the type of rigor needed when you want to invent a new service, product, or process (or overhaul something that is already in place). Myles Burke of Lockheed Martin, who’s been mentioned frequently in this book, found that some of the procurement processes were so complicated, and had so much variation from person to person that he gave up on value stream mapping and went into process redesign. There was just no way that procurement was ever going to satisfy its 14 external customers in terms of lead time with improvements to the existing “process” (using the term loosely).

In Caterpillar’s case, you couldn’t really say the value stream was “broken” because it had never existed at a macro level in the company. A rough cut at the cost benefit showed it might be worth $500,000 in hard savings per year for a relatively modest investment of available resources (that is, the “lead time to results” was favorable). The key would be pulling together all the disparate pieces into one coherent value stream designed to meet their business needs and those of the people using the credit card system.

[1]Kimberly Watson-Hemphill is a Master Black Belt with George Group Consulting and lead author of their Design for Lean Six Sigma curriculum. She has trained and coached hundreds of Black Belts and Master Black Belts throughout North America and Europe. She has a wide background in all areas of Lean Six Sigma, new product development, and project management and has worked with Fortune 500 companies in both service and manufacturing industries. She is a certified Project Management Professional, has a Bachelor’s degree in Aerospace Engineering from the University of Michigan and a Master’s degree in Engineering Mechanics from the University of Texas.

[2]Rod Skewes is a Master Black Belt with Caterpillar Inc. covering administrative areas such as Accounting, Treasury, Tax, Auditing, and Legal Services. His career at Caterpillar has spanned more than 16 years and included economic analysis and forecasting, marketing research, and accounting before joining Caterpillar’s 6 Sigma effort. He is a Certified Management Accountant, has a Bachelor’s degree in Business Administration from Morehead State University in Morehead, KY, and a Master’s degree in Agricultural Economics from North Carolina State University in Raleigh, NC.

Designing Services with DMEDI

The key issue when you want to design a new product, service, or process (or overhaul an existing process to the point where it’s almost like starting from a blank slate) is that there are a lot more unknowns than when you are just tweaking what you already have. You don’t really know what customers want. You don’t really know which models or approaches are workable. You may not have existing capabilities to provide the needed functionalities.

The preferred improvement model used for these situations goes by a number of names: DMEDI (for Define-Measure-Explore-Develop-Implement), DMADV (for Define-Measure-Analyze-Design-Verify), or just Design for Six Sigma or Design for Lean Six Sigma (DFLSS). In this chapter, we use the terms DMEDI and DFLSS interchangeably. Though the labels differ, all are basically business strategies for executing any high-value projects that require a significant amount of new design. They all incorporate a greater emphasis on capturing and understanding the customer and business needs than does DMAIC, and establish clear links at every step from translating “needs” into “requirements” and ultimately to the processes used to create the new service or product. While DMEDI requires additional tools, it builds on the basic DMAIC methodology, and remains fact-based and data-driven:

Define: The project team comes together with its sponsor to develop well-defined charter that has clear ties to the business strategy and line-of-sight linkage to significant financial benefits

Measure: The team focuses on understanding the Voice of the Customer, information that will be used to design best-in-class products and services

Explore: The team innovates to develop multiple solution alternatives and selects the most promising concept and confirms a high-level design

Develop: The team uses Lean and Six Sigma tools and simulation to create a robust design

Implement: The design is piloted, a control plan is developed, and the new product or service is launched

In addition, all the process management basics established for DMAIC apply to DMEDI (see sidebar, next page).

Like many of the methods discussed in this book, Design for Lean Six Sigma (DFLSS) arose in manufacturing (in product development departments). But DFLSS tools work as well for designing services and processes as they do for products, and the overarching methodology evolved in what is essentially a service function (design). DFLSS has been successfully used on a wide range of service projects, such as developing new marketing channels for existing offerings, IT solution development and outsourcing, establishing a new process for managing intellectual property, developing new financial services offerings, and so on. This chapter walks through the DMEDI model, using the credit card case study introduced at the beginning of this chapter to illustrate the key activities and tools in each phase.

Using DMAIC for Product/Service Design

Caterpillar uses both DMAIC and DMEDI in the new product introduction process. DMEDI tools are preferred when, as described in the text, the number of unknowns is large or addressing a customer need requires significant new knowledge or capabilities.

All the DMAIC basics apply

Design for Lean Six Sigma projects—under the names of DMEDI or DMADV—are run using the same infrastructure and guidelines described for DMAIC teams:

- Projects are led by Black Belts with help from Master Black Belts, Champions, and Process Owners.

- Broad, cross-functional teams work on projects to mitigates risk and develop a solution that is acceptable to all areas of the business.

- Software tracking tools allow the executive team to monitor overall program status and financial results.

- Projects should be managed and monitored as usual, with Phase/Gate reviews between phases conducted by the Champion and sponsor(s)—this guards against having a team just dive into developing a process/service/product without proper decision making along the way.

- Design teams should be part of a project Pull system (where the number of projects is limited by the capacity to work on them).

Define

The key objective of the Define phase is the development of a well-defined charter. The elements of a DMEDI charter are similar to those discussed in Chapter 11 for DMAIC projects: a product/service description, business case, project goals, project scope, a high-level project plan, and team members. The charter should be sufficiently detailed so that the business objectives and the scope are clear to both the team and the management.

In addition, there are two major elements of risk to be considered in a DFLSS project. First, the risk that the project will not meet its objectives, which would primarily be a risk to the schedule and to benefits (technical, cost, schedule, and market risk). Second, there are the risks that the project poses to other elements of the business.

Phase Gate Review for Define

To advance to the Measure Phase, the team should have a solid charter with a validated business case and a clear, attainable scope and ROIC. A cross-functional team should be created, with representation from different areas that will be affected by the project and a balance of effective team roles (as discussed in Chapter 10). Initial planning work on communications, project management, and risk should be complete.

CASE STUDY: Caterpillar Global Credit Card Project – Define Phase

When confronted with all the questions it could not answer about corporate credit cards, Caterpillar formed a global team consisting of representatives from corporate treasury, corporate travel, corporate accounts payable, shared services (United Kingdom), European tax, the Geneva subsidiary, and Asia Pacific treasury. Initial efforts showed that no process currently existed, so the team knew it would need to follow the DMEDI model to develop something that would meet Caterpillar’s needs.

The charter stated that the project should quantify the number of cards currently used globally by Caterpillar, the total dollar amount of credit card purchases, and the cost to administer the cards. The team would then investigate and implement improvement alternatives.

The Business Case

Caterpillar is currently receiving significant rebates on cards for U.S. operations. The expectation was that that amount could be doubled if the team looked at the purchases outside those covered by the current U.S. program. Targeted benefits included:

- doubling rebates (financial incentives) received by Caterpillar

- improved VAT tax recovery (the European equivalent of sales tax)

- improved ease-of-use for employees who are traveling and doing business around the world

- visibility of purchases for greater purchasing leverage

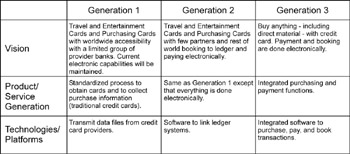

The team managed the scope with a multigeneration plan (see Figure 14.1). The current project would establish a worldwide program for Caterpillar’s two basic types of credit cards (Travel & Entertainment and Procurement) using a limited number of provider banks (the ultimate target was one bank, but that would turn out not to be achievable), and maintaining current electronic capability for those areas who had it. This would be supported with a standardized process to obtain cards, collect purchase information, and collect data. All information would be connected electronically worldwide from all credit card providers.

Figure 14.1: Multigeneration Plan for Global Credit Card Project

Complexity Prevention vs. Complexity Cures

Recent advances in Design for Lean Six Sigma include a focus on reducing product and service complexity—both non-value-add (transparent) complexity, that which is invisible to the customer, and also customer-facing complexity, which exists in features and functions thought to be desired by the customer, but that don’t add shareholder value. As you may recall from Chapter 5, the key is to use a platform design approach, where you standardize as many components, steps, modules, etc., as possible. This platform approach is a complexity “prevention” technique that served external customers; the process/service redesign case in this chapter is a complexity “cure” that affects internal customers. In both cases, the team had to incorporate a deep understanding of the Voice of the Customer in all phases of the project.

Measure

The key objective of the Measure phase is to understand the Voice of the Customer (VOC)—or Voice of the “Process Partner” if you’re working on an internal process (see sidebar, below)—and to translate the customer feedback into measurable design requirements. Chapter 3 discussed a wide range of techniques for capturing VOC data; the discussion here focuses on the tools and methods most helpful in design efforts. The degree of VOC emphasis may come as a surprise to those who have only been involved in DMAIC projects in the past. While customer needs play a central role in shaping priorities in a DMAIC project, here, a good understanding of customer needs is the single most important determinant of success.

Capturing the Voice of the Customer

The first step in capturing the Voice of the Customer is determining the appropriate customer segment. While in theory anyone in the world could buy your services, there is a particular subgroup, or segment, that is most likely to buy. If you’re interested in achieving maximum performance, you want to focus your products and services on the customer group where it is most likely to resonate in the marketplace. Customers should be segmented or grouped according to similar needs. Focus on the customer segment(s) that aligns with corporate strategy, are attractive from a size and profitability standpoint, and align with the business’s capability to satisfy them.

Once the customer segments are known, they need to be prioritized. As with other areas discussed in this book, the Pareto principle works here: 20% of your opportunities will bring you 80% of the value. (That is, the greatest value may come from a small portion of the customer base.)

Internal Customers or Process Partners?

A central tenet of Lean Six Sigma and most other quality methodologies is that “only customers can define quality.” Historically, a distinction was made between “internal customers” (those to whom an employee hands off work) and “external customers” (the end purchaser or user).

Some companies, like Caterpillar, have found it helpful to reserve the term “customer” for those who purchase and use the end product or service—because they ultimately determine a company’s fate in the marketplace. What used to be called “internal customers” are now called “process partners” to emphasize the idea that everyone inside the company should be working together to best serve the ultimate customer.

Start the VOC process by taking advantage of existing and available information (see sidebar, below). Once you understand the gap between what customer information you already have and what is needed, use proactive methods to gather additional information. The most important part of using any of these techniques is having the approach well planned in advance.

Typical existing sources of customer information

Every company has customer contact that can provide a baseline for service/product design. Some sources to look at are complaints, compliments, returns or credits, contract cancellations, market share changes, customer referrals, closure rates of sales calls, market research reports, completed customer evaluations, industry reports, available literature, competitor assessments, web page hits, or technical support calls.

If you survey customers and ask which features they would like to see in your services, they will undoubtedly say, “All of them!” However, customers attach different values to feature combinations, and we know that there are certain features that would be preferred by the customer over other options. That’s why the process described below incorporates a rating by customers of the importance they place on different features or functionalities. You might also benefit by doing a Kano analysis, where service or product features are separated into three categories (expected quality vs. normal quality vs. exciting quality) based on customer expectations (see the original Lean Six Sigma book, pp. 140-142, for details).

Translating needs into requirements

The next step is to translate the Voice of the Customer into the Voice of the Designer. The method to do this is called Quality Function Deployment (QFD), a highly structured and very effective approach for converting customer needs into design requirements. The secret to QFD’s success is that it establishes design requirements that are:

- Measurable (quantifiable)—so you can tell if you met them

- Solution-independent, meaning the requirements aren’t linked to predefined solutions that the design team might have in mind (allowing for much greater creativity)

- Directly correlated to customer needs, so you know that you’re addressing issues that are important to customers

- Easy to understand

To achieve these goals, QFD walks through a series of steps:

- Identifying customer needs from the VOC data you gathered

- Prioritizing those needs

- Establishing design requirements that address all customer needs

- Prioritizing the design requirements (to focus the design effort)

- Establishing performance targets

These steps are linked together very deliberately, so that at the end you can trace a path directly from customer needs to specific elements of the service/product design. Along the way, you’ll be asked to answer questions such as:

- What are your current strengths and weaknesses relative to the competition?

- How do these strengths and weaknesses compare to the customer priorities?

- Where are there gaps that need to be closed?

- Are their opportunities to learn from the competition?

- Are their opportunities for breakthroughs to exceed competitors’ capabilities?

- Are there any customer needs that you do not know how to measure? If yes, how will you meet these needs?

- Are there design contradictions that cannot be resolved?

- Are the performance targets achievable?

The team will also assess the impact of failing to meet the targets and specifications, including an assessment of different risks (to the customer, to the business) and whether the organization’s current competencies are well matched to meet the performance targets. Because there is so much learning about the project in the Measure phase, teams often discover quick wins: changes that look to be a sure thing, are easily reversible, and require little or no investment. The team should take advantage of quick wins as soon as possible, and begin accruing financial benefits. A Kaizen event (see p. 52) can be conducted to facilitate immediate implementation.

Phase Gate Review for Measure

The Measure phase closes with a Phase/Gate Review. The team and the leadership should feel that the Voice of the Customer is thoroughly understood, and that clear design requirements have been established. The team will have assembled critical metrics and begin tracking them on a scorecard. The next phase will generate high-level concepts.

CASE STUDY: Global Credit Card Project – Measure Phase

The focus of the Measure phase was to understand the Voice of the Process Partner via a series of global surveys. The surveys addressed the needs of Cat’s “Road Warriors” (frequent travelers), of those using procurement cards, and of the business.

Survey #1: Voice of the Business

This survey was sent to all business units so the team could understand what business requirements a global credit card system would need to meet, and to gather data to shape the requests for quote they would later send to potential vendors. Sixty responses were received, covering all major business units. There were many different provider banks for 25,000 cards total, working in 23 different currencies, and almost 800,000 transactions a year. The fees varied widely, and there were virtually no rebates being collected outside of the United States. Administrative costs were also quantified for the first time.

What turned out to be important to the business units was:

- worldwide acceptability

- good expense reporting capability

- flexibility in purchasing card usage

Respondents also indicated they’d be interested in combining Travel & Entertainment and Procurement cards, which Caterpillar hoped would reduce process complexity.

Survey #2: Voice of the Process Partner (Travelers)

220 surveys went to frequent travelers in Europe, Asia, Australia, and the U.S. The heart of the survey was a list of 17 credit card attributes that the travelers rated on importance. Responses showed that all 17 features were critical, and no additional feature requirements surfaced from a user standpoint. (Conveniently, all of these features turned out to be present in most card offerings that were later considered.) The survey also gathered information about where customer satisfaction was the highest and lowest among provider banks.

Survey #3: Voice of the Process Partner (Procurement)

136 Procurement Card users worldwide were surveyed. This survey polled customers on the importance of 12 key criteria. Similarly to the previous survey, all were deemed important, and no criteria added. Information about high and low quality providers was also tracked.

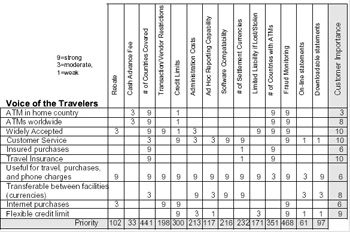

Armed with the Voice of the Process Partner, the team developed a series of QFD houses. The first house took the needs from the surveys and translated them into measurable critical requirements (see Figure 14.2, next page). The requirements that were the most important were that (1) the card would be useful for travel, purchases, and phone, (2) the card would be accepted in many countries, (3) transferability between Caterpillar facilities, (4) software compatibility, and (5) the number of settlement currencies.

The next house of quality transferred the requirements to more detailed card functions, or design requirements. This house was instrumental in providing criteria for evaluation of different designs in the Explore phase.

The Gate Review confirmed that the project was on track to achieve anticipated benefits.

Figure 14.2: First House of Quality (excerpt)

This is an excerpt of the first House of Quality the Caterpillar team developed as part of the credit card project. This house relates customer (or “Process Partner”) statements of needs (left column) to critical requirements (top columns). The individual scores for each requirement are multiplied by the importance (far right), then summed at the bottom to get a Priority rating.

Explore

After defining requirements, the team needs to answer the question: What is the best way to meet our customer needs at a conceptual design level?

This is where innovation occurs. Usually, teams will discover that there are conflicts between customer needs and the company’s ability to meet those needs, conflicts between different design parameters, or conflicts between cost and performance. Often, trade-offs or compromises are made—though finding solutions to resolve these conflicts rather than compromise leads to more innovative products and services.

At the Measure Phase/Gate Review, the team has to convince its sponsor and other leaders that it has a solid understanding of the Critical-to-Quality (CTQ) customer requirements. Now they have to combine that market and customer knowledge to generate specific concepts. The reaction at this point? “Now that we’re about to work on solutions, how do we get started?”

Functional Analysis

Every service or product has certain things that it must do in order to perform acceptably from a customer’s viewpoint. Functional analysis breaks the service down into its key tasks. This will help generate multiple solution ideas for each function, usually displayed in a tree diagram. Functional analysis also helps break down the problem into more manageable pieces to improve the odds of developing the best concepts. For example, rather than brainstorm concepts for a new fast-food service at a system level, the team would identify the functions (take order, fulfill order, collect payment) and then brainstorm solutions for each of the functions (e.g., take order—pencil and paper, cash register buttons, Internet).

In the Measure phase, the team developed the first House of Quality with QFD (see Figure 14.2, p. 372). Here, they continue working with the QFD matrix, completing House 2, which links the functions with the design requirements. The goal is to prioritize the functions that have the strongest link to the Voice of the Customer/Process Partner, because those will be the foundation of any new design. You can also use this work to flow down the high-level design targets into smaller design elements.

In completing House 2, the team will understand what functions the product/service must have, and how those functions rate in priority. Now they will investigate how those functions can be filled. The secret here is to be as creative as possible:

- Brainstorm ideas: With a little creativity and planning up front, brainstorming can be both a great source of new ideas and a lot of fun! There are many different twists on idea generation to help spark creativity within the team. (Check any good facilitation book for many different types of brainstorming.)

- Use Benchmarking to broaden awareness of what already exists out in the marketplace, and also what’s possible. If you use benchmarking in this context, be sure to look at best practices that exist elsewhere in your organization, not just what other companies are doing. Review your existing products and services for ideas: Are their some technologies that you have used in other areas that might be of advantage for this new product/service? In the past, what have you done particularly well?

- If you are working on consumer products or services, visit places (such as local stores) where customers purchase or use the type of product or service you’re designing or visit customer sites to observe similar products/services in use.

Create an open atmosphere

Most teams find Explore to be the most enjoyable part of DMEDI because they of the creativity. The team leader and coach should work to create a team environment that is open to new ideas, and to prevent teams from latching on to any one solution too early. Most importantly, the team leader should act as a facilitator, cultivating and emphasizing inquiry vs. advocacy skills learned in team leadership training.

After generating many interesting concepts, the team will need to narrow the field to the one or two most promising alternatives. (Notice the key assumption that the team has multiple concepts to consider!) You want to be sure that all feasible alternatives have been explored before deciding on a single concept. World-class innovations don’t come from a one-horse race. If the investigation of concept ideas only brought about one or two options, it is strongly recommended you develop a plan to create additional options before moving forward.

Explore tools

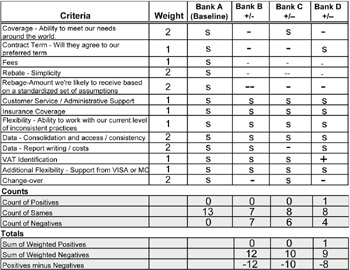

A powerful tool to synthesize and select concepts is the Pugh Matrix. The team establishes the evaluation criteria from the Voice of the Customer and the Voice of the Business, and weights the criteria using an analytical tool such as the Analytic Hierarchy Process (an advanced form of pairwise comparisons where stakeholders can both compare the criteria and weight the differences). Once the criteria and weights are established, each concept is compared against the other concepts on the individual criteria, assigning pluses where the concept is superior and minuses where it is inferior.

Each concept will need to be developed sufficiently so that it can be compared to the other alternatives for each criteria. Information such as cost and time to implement will need to be gathered before the comparison process. This will lead to determining the winning concept. However, another significant benefit of the Pugh process is the opportunity for idea synthesis, generating even better concepts based on enhancing the pluses and minimizing the minuses of the different alternatives. (See the example of a Pugh matrix in the Caterpillar case study, p. 377.)

Phase Gate Review for Explore

The Gate Review for the Explore phase presents the conceptual alternatives to the leadership and walks them through the process that the team used to select the winner. The high-level design is presented. Depending on the project, it may be necessary to have an additional leadership review earlier in the phase to get feedback on the initial concepts. For example, if the project involved selecting a software vendor, the team would want to make sure that the leadership agreed with the selection of potential providers. Get feedback sufficiently often so that the project does not backtrack. The end of the Explore phase is too late to realize that your team overlooked a concept that the management team sees as a viable alternative.

CASE STUDY: Global Credit Card Project – Explore Phase

In the Explore phase, the team took the prioritized functions that needed to be provided by all concepts and developed a high-level design. For this program, the high-level design would be the proposal from the bank (or banks) selected as the prime candidate to provide the service worldwide. Steps included:

- Developing a list of requirements

- Developing a Request for Information (RFI), which covered 22 questions corresponding to the prioritized functions in the second House of Quality

- Sending the RFI to 10 banks, selected from current Corporate banks and current Credit Card providers

- Evaluating the responses from the 7 (out of 10) banks that responded, and selecting 4 of those banks for further investigation

- Sending a formal Request for Proposal (RFP) to the 4 selectees

- Selecting a final provider based on the responses

The proposal from the finalist was the preferred high-level design taken into the Develop phase.

The key tool utilized in this phase was the Pugh matrix (see Figure 14.3, next page), used to evaluate responses to the RFI and RFP. As it turned out, credit cards are mostly a commodity business from a user point of view, so all the providers scored about the same on those criteria. The differentiators arose in the Voice of the Business criteria. The key differentiators for the winning bank were that the rebates were the simplest and most robust, the bank offered the lowest fees, and also offered a single global contract. Caterpillar also had a long standing credit card relationship with the winning bank, so their performance history was known.

Figure 14.3: Pugh Matrix of Provider Candidates

With utilization of the Pugh matrix and clear criteria for the preferred bank, it didn’t take the team long to select a winning bank/proposal. Caterpillar would have a process by which they could offer cards around the world that had an established, known level of service quality with little variation. In addition, Caterpillar would now have availability of the purchase data put on those cards, along with significant financial gains.

At the Gate Review, the team reviewed previously identified risks and determined that the project was on-track to move forward. The leadership also acknowledged that the implementation time-frame would be driven by contract negotiations.

Develop

The Develop phase is where the detailed design occurs. In addition to designing the core service, attention should be paid to developing information technology elements of the project, establishing a plan for human resources, developing sites/facilities, and purchasing materials that will be required for implementation.

As the solution is developed, the team should take advantage of Lean and Six Sigma tools to maximize speed and minimize waste in the new process. In particular, Value-Added Analysis is beneficial to many projects. The process map of the to-be service is reviewed and each step analyzed and assigned to one of three categories, as discussed in Chapter 4:

- Customer Value-Add – Tasks that the customer would be willing to pay for (i.e., adds value to the service, provides competitive advantage)

- Business Non-Value-Add – Tasks required by business necessity (i.e., financial reporting) but that do not provide value to customers

- Non-Value-Add – All other tasks (approvals, rework, waiting)

Develop tools

The Develop tools in DMEDI are similar to the Improve tools in DMAIC, including:

- Mistake-proofing (or poka-yoke, its Japanese name) is the science of preventing defects before they occur. Pull-down menus and pre- formatted data fields in technology solutions are just two examples.

- Design optimization and refinement can be done through Design of Experiments (DOE). DOE is a systematic methodology where input factors are varied to understand their impact on the output of interest, and a cause-and-effect relationship can be determined. In a service environment, outputs would be important outcomes of the project, such as cycle time, cost, revenue, efficiency, or customer satisfaction.

Phase Gate Review for Develop

The Develop Gate Review presents the detailed design to the leadership team and solicits their feedback. Keep in mind that depending on the size and complexity of the project, an additional review might be needed mid-phase.

CASE STUDY: Global Credit Card Project – Develop Phase

The objective of the Develop phase was to take the concept of the program (from the winning bank and team’s ideas), turn it into specific contract language, and prepare for global implementation. The first contract draft didn’t match the team’s expectations, so the team reviewed their current skill set and decided that additional expertise was needed. They hired legal counsel with banking expertise to review aspects of the contract and also hired a consultant with significant credit card industry experience to help optimize the functionality. While these costs were not identified in the project charter, the team obtained permission for the extra expenditures from their management sponsors.

Concurrent with negotiations, the team reviewed the process that would be needed internally and evaluated it from a design element standpoint: service/process description, process methods, human resources, information systems, and materials. The team prepared for implementation by finalizing the process owner (Corporate Treasury), designating an ongoing process management team, and developing a detailed communication and rollout plan. The Develop phase concluded with a gate review after the contract was finalized. Based on a review of the project scorecard, the project continued to be on track to meet all of its objectives.

Implement

The objective of Implement is to successfully conduct a pilot, transfer ownership of the project to the new process owner, and implement the new service (very similar to the Control phase of DMAIC). One of the key benefits of Six Sigma methods is the rigor around implementation and process control. Everyone has worked on a project that started off well only to watch it fall apart when the solution was implemented. With solid up-front work in the Implement phase, these issues can be avoided.

CASE STUDY: Global Credit Card Project – Implement Phase

This project is currently on track for a global implementation in 2003, with improved functionality for the travelers, a simplified process, better data gathering, and significant financial benefits. A pilot is planned for the UK, as a first step in the international launch. Controls are being developed that will maintain the improved functionality through the life of the program.

Part I - Using Lean Six Sigma for Strategic Advantage in Service

- The ROI of Lean Six Sigma for Services

- Getting Faster to Get Better Why You Need Both Lean and Six Sigma

- Success Story #1 Lockheed Martin Creating a New Legacy

- Seeing Services Through Your Customers Eyes-Becoming a customer-centered organization

- Success Story #2 Bank One Bigger… Now Better

- Executing Corporate Strategy with Lean Six Sigma

- Success Story #3 Fort Wayne, Indiana From 0 to 60 in nothing flat

- The Value in Conquering Complexity

- Success Story #4 Stanford Hospital and Clinics At the forefront of the quality revolution

Part II - Deploying Lean Six Sigma in Service Organizations

- Phase 1 Readiness Assessment

- Phase 2 Engagement (Creating Pull)

- Phase 3 Mobilization

- Phase 4 Performance and Control

Part III - Improving Services

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 150