Integrating Two Cultures

|

Like many in its industry, a large and well-known public corporation (“Company A”) made several acquisitions in the past decade in both its core and related businesses. At one point, it acquired another large institution (“Company B”) with operations in several of the markets that it served. This transaction was driven by a desire to expand its geographic presence and operational scope, capture the other’s operations abroad, and achieve still greater scale advantages in a highly competitive industry.

In light of these goals and the similar operational characteristics of the two institutions, this combination was a nearly perfect candidate for full integration that would require the following:

-

Uniformity of processes to create value

-

A common set of products and/or services capable of meeting customers’ needs

-

A single public face

However, the merger could not be expected to be easy. The companies had been rivals for some of the same turf; Company B’s brand had even eclipsed Company A’s in some areas. The two corporations had different information systems. Just as daunting, they had different people policies and practices whose integration could be both painful and risky. However, as a result of its experience with acquisitions, Company A had great confidence in its ability to bring the new entity into the fold. Over the years it had developed an approach to integration that was based on (1) speed and (2) adapting the acquired company’s systems, practices, and procedures to its own. The size of this transaction, however, caused it to pause and reflect on its integration practices. It asked: Is this the best way in this case?

Our involvement in this situation came about at the behest of Company A, which was eager to understand similarities and differences in the human capital systems of two organizations before making any drastic changes.

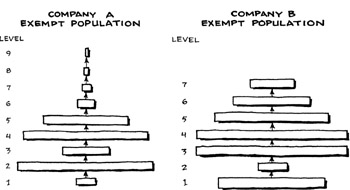

We began, as always, by gathering the facts from the two entities. What were the rates of movement of employees into, out of, and upward in the two organizations? How were rewards structured and what did they value: years of service, performance, movement from job to job? To answer such questions as these, we conducted Internal Labor Market (ILM) analyses for both companies, starting as usual with the basic ILM maps of labor flows. The maps themselves tell a story (Figure 8-3).

Figure 8-3: International Labor Market Maps Company A & Company B

The ILM map of Company A reveals an organization with a steep hierarchy with many employees in the lower levels and dramatically fewer people at higher levels. Company B, in contrast, is relatively less hierarchical. Its map indicates a more equal distribution of employees through the various job levels and much less thinning out toward the top.

Investigation revealed that the two firms had very different reward systems attached to their respective job levels. At Company A, moving up through levels produced sizable financial rewards that rose at ever increasing rates – what we called in Chapter 1 a “tournament” reward structure. That practice encouraged a career orientation among Company A’s employees, who apparently understood that simply doing satisfactory work and sticking with the company would not be rewarded anywhere near as much as moving up the career ladder would. Although in most lower- and middle-level jobs they were paid somewhat less than were their counterparts at Company B, their upward “pay trajectories” were more dramatic, encouraging retention and a willingness to develop careers with the company. Company B’s employees actually could advance more rapidly, as the high numbers of individuals above the mid-mark of job levels testified, but advancing up the ladder produced less dramatic pay increases. Company B’s employees could be consoled by the fact that they were nevertheless paid at or above market rates. Above-market pay encouraged retention.

The bottom line was that Company A had a career culture while Company B had a pay culture. Which was better? That did not matter as long as (1) the companies were independent and (2) the workplace culture served the respective company’s strategic goals. Integration changed this. Management had to determine which culture would best serve the strategy of the combined entities. That determination was made more interesting by the fact that some key executives from Company B were retained in high-level positions in the combined entity. Being accustomed to an environment with fewer job levels and a more market focused, pay-oriented culture, they urged Company A to move in that direction. Those features, they believed, were easier to manage and produced good results. However, Company A’s management understood the singular importance of their career culture for retaining top-flight employees. They also recognized that such a culture could better serve the strategic goal of strengthening and growing relationships with customers because it fosters longer-term commitment to the organization among employees. Not surprisingly, the new combined organization maintained a strong career orientation.

|

EAN: N/A

Pages: 134