MacArthur at Inchon

MacArthur s amphibious assault at Inchon during the Korean War in 1950 is widely regarded as one of the boldest attacks in modern military history. MacArthur himself even acknowledged , with typical bravado and embellishment , I realize this is a 5,000 to 1 gamble, but I am used to taking such odds. [2] But this risky move was well rewarded: the successful landing at Inchon led to the capture of Seoul and isolation of North Korean forces to the South, thereby dramatically altering the momentum of the war.

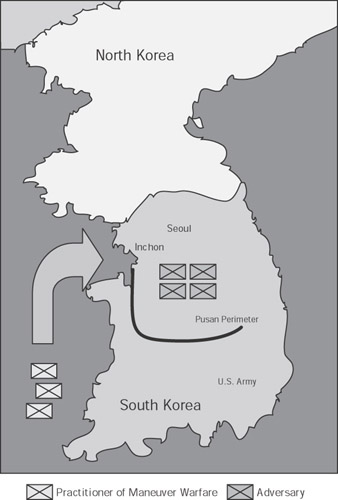

By September 1950, the North Koreans had pushed the U.N. forces to the southern tip of the Korean peninsula, in what became known as the Pusan Perimeter. With the harsh Korean winter looming, MacArthur knew that he had little time to make a deep and decisive blow to break this static front. He chose Inchon, a port city on Korea s western coast , because it offered a direct route to Seoul and because it was the worst possible, and therefore least defended, location for an amphibious landing.

Figure 5.1: MacArthur s Amphibious Assault, 1950

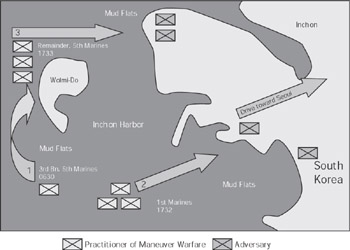

A landing at Inchon would be possible on only one day during the month of September ”the 15th. On this day the tides, which varied by as much as thirty-one feet, would reach their extreme highs for three hours in the early morning and three hours in the late afternoon. A failure to land during these narrow windows of opportunity would leave the U.N. forces stranded helplessly on Inchon s unforgiving mudflats and exposed to enemy fire. Further complicating the landing, the narrowness of the channel would force a two-stage landing, completely eliminating the element of surprise. Finally, upon reaching the shore, the landing force would have to scale, one by one with makeshift ladders, an imposing seawall.

MacArthur faced stiff opposition from his Army, Navy, and Marine Corps counterparts in the Korean theater and from the joint chiefs of staff and political forces in the United States. Despite his history of success and his reputation for avoiding unnecessary risks, MacArthur s detractors saw Inchon as too risky and therefore advocated landing on a beach that didn t offer nearly every natural and geographic handicap. [3] But MacArthur was steadfast in his commitment to his scheme of maneuver, which embraced these handicaps in an effort to avoid a landing opposed by strong and entrenched enemy forces. Building a brilliant invasion plan and meticulously backing it with ample tactical facts, he systematically persuaded skeptics, even President Truman, and ultimately achieved the consensus he needed.

MacArthur made every possible effort to stack the odds in his favor. Preparing for the difficult assault was no exception. To minimize uncertainties surrounding the challenge that lay before him, he assembled a team of oceanographers, cartographers, intelligence agents , and even scout swimmers that reconnoitered the Inchon Harbor a week before the invasion. As a result of the efforts of this diverse team, MacArthur knew the exact timing and duration of the tides, the location of all natural underwater obstacles, the layout and composition of the beaches, the height of the seawall (five to eight feet), the width of the channel and landing areas, the location and disposition of enemy forces at Inchon, and how long enemy reinforcements would take to arrive .

Figure 5.2: Landing and Attack at Inchon Harbor, September 15, 1950

On the morning of September 15, nearly three hundred ships in the Pacific, including Japanese and American merchant ships, were pressed into service to support the seventy-thousand-strong invasion force. At 6:30 a.m., the initial assault force of U.S. Marines landed successfully and captured Wolmi-Do, the small but well-fortified island at the mouth of Inchon Harbor. The Marines held Wolmi-Do for the remainder of the day until a second wave of U.S. Marines, the main assault force, hit the beach at about 5:30 p.m. By midnight the landing force had moved inland and secured Inchon, at a cost of 22 killed and 174 wounded ”far less than anyone had expected. [4]

With Inchon secured, MacArthur dispatched a giant follow-on force through the opening created by the Marines and pressed on to Seoul. Within two weeks he captured Seoul, severed the North Koreans logistical and communications lines, and cracked the Pusan Perimeter.

Leadership Lessons

MacArthur s brilliant plan and masterful execution exemplify boldness on four counts. First, he had the courage to stand behind his convictions in the face of considerable organizational resistance and eventually managed to convince opponents of the invasion to support his plan. Second, he identified a breakthrough opportunity and acted decisively to turn it into a breakout gain. Third, his exhaustive planning efforts mitigated many of the risks associated with the huge gamble he was taking, thereby creating a more favorable risk-reward profile. Finally, the indirect attack on the North Koreans at Inchon unfroze the static front to the south at the Pusan Perimeter.

[2] Perret, Geoffrey, Old Soldiers Never Die , 547.

[3] Ibid, 546.

[4] Miller, Nathan, The U.S. Navy: A History , 253.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 145