Logical Structure Design

| < Day Day Up > |

| When you develop the logical design, it is essentially the development of the forest and domain structure, including the OU structure, Global Catalog (GC) server planning, naming standards, Group Policy, and trust definitions. The fundamental components of the logical structure are illustrated in Figure 5.1. Because this book covers migration from Windows NT and Windows 2000 to Windows Server 2003, this section deals with logical design details needed in developing a new AD structure, as well as considerations if you already have a Windows 2000 domain structure in place. In today's business climate of seemingly continual mergers and acquisitions, few companies can consider their forest structure set in stone. In addition, the experience the Windows community has gained since the release of Windows 2000, along with new capabilities of Windows Server 2003, has provided motivation to re-evaluate the forest structure. This chapter presents current design techniques and strategies to help you design your infrastructure or make changes that might be driven by a merger, acquisition, or business needs. Figure 5.1. The AD logical structure. Your organization's logical structure includes the forest structure, domain structure, and OU structure, and is commonly referred to as the design of the namespace. These elements form the foundation for all other aspects of AD, so it's critical to incorporate the right design for your organization. Domain and OU StructureThe three basic domain structures illustrated in Figure 5.2 are the single domain model, the multiple domain model in a parent/child relationship, and the multiple domain model in a multiple domain tree relationship. In each model, OUs are used to create subdomain organizations for more granular administration and security purposes. Note that OUs contain nearly anything a domain can contain, including users, computers, printers, groups, shares, Group Policies, and even other (nested) child OUs. Administration of the OUs is delegated from a higher-level container (domain or parent OU). Figure 5.2. Basic domain structures in AD. This section details the differences and design considerations of multiple- versus single domain models. The decision really rests with the question "Can I accomplish my design criteria more effectively with OUs or domains?" To help determine this, refer to Table 5.1 to compare features of domains and OUs. Note that multiple domains are clearly more rigid and add to the complexity of the AD, as well as being more costly because you must add servers to create and support the additional domains. Table 5.1. Domain and OU Feature Comparison

note OUs are significantly restricted, in that even though it is available in the Group Policy Editor, account security cannot be applied at the OU level. For example, you cannot set the Maximum Password Age to 60 days on the domain level and then set it to 30 days at an OU. Actually, you can set it at the OU, but it won't apply. This applies only to the Account Security settings and not to User Rights or Audit Policy or any other setting configured in a Group Policy. Windows Server 2003 does not change this behavior. Note also that DCs are in a world of their own on application of security policy, an issue we discuss in the "Account Security" section of this chapter. This behavior is noted here because this security restriction could dictate the necessity of creating domains rather than OUs if separate password policies are required for different business entities. However, if different business entities truly have different security requirements, it might be more advisable to create multiple forests, instead of different domains. Microsoft has been advising customers even before Windows 2000 was released that the best AD design strategy was to begin with a single domain and prove you need more. After nearly five years of experience with AD, we can say that this design principle is still true. That is not to say that a single domain will always suffice, but that exercise will force you to justify additional domains. Single DomainThe single domain, as illustrated in Figure 5.3, is well suited for small- or medium- size companies with simple business organization models, as well as a large global enterprise. Microsoft itself implemented a multiple domain model and is now attempting to collapse it to a single domain model for security reasons. Remember that the key design principle is to create domains representing entities that do not change, and to use OUs for entities that do change (such as business units). Business unit names , location in the organization hierarchy, and subordinate organizations not only change, but also sometimes disappear altogether. Figure 5.3. Single domain structure. Creating domains based on business entities guarantees a lot of work for the system architect and Administrators, because changing organization structure and department names require changing the domain structure and names. As I worked with companies to design their AD models, it became clear that the most popular domain model is to name domains after geographical entities, such as Americas, North America, South America, Latin America, EMEA (Europe, Middle East, Africa), and Asia Pacific. As one designer noted, "The globe never changes." Thus, it becomes easy to see that a company just doing business in a single country or region would be a good candidate for a single domain model. College campuses would fit well in this example. Some features that qualify you for a single domain model include

Although Microsoft and experienced AD architects usually recommend that you start with a single domain model and then prove you need more domains, there are some very good reasons to implement a multiple domain model, as described in the next section. Multiple DomainsMultiple domain structures are probably the most common AD configuration. Even in small organizations, multiple domains can have advantages. As I noted in the "Single Domain" section, multiple domain models are almost always named after geographical entities. One of the design practices to evolve as Windows 2000 was deployed in the past few years is the role of the empty root domain , also referred to as a "ghost" or "placeholder" domain. This domain contains enterprise Admin and schema Admin accounts, and serves as the forest root domain, which holds the domain structure together. It can be implemented either as a parent to the other domains or a separate domain tree, as shown in Figure 5.4. Compaq implemented a placeholder domain in a parent-child relationship. Figures 5.5 and 5.6 illustrate how Compaqtrimmed more than 1,300 resource domains and 13 master user domains (MUDs) to a simple 4-domain structure in a parent-child relationship. Figure 5.4. The empty root domain can be implemented in a parent-child structure or as separate domain trees. Figure 5.5. Compaq's Windows NT domain structure (prior to merger with Hewlett Packard). Figure 5.6. Compaq's Windows 2000/2003 domain structure. HP was migrated into this structure after the merger. This is the current HP Windows Server 2003 domain structure. I know consultants who have advised their customers to create a placeholder domain even if a single domain model would be sufficient. Their reasoning was for expansion. In reality, if you did create a single domain and later wanted to implement a placeholder domain structure,you could create additional domains and leave the original as the placeholder, migrating users, computers, groups, and so on to the other domains. Consider the case of the Georgia (United States) Department of Transportation (GDOT), profiled in Appendix A, which moved from a multimaster full mesh Windows NT domain model (shown in Figure 5.7) to a two-domain model with an empty root for its Windows 2000 infrastructure (shown in Figure 5.8). Essentially, this is a single domain model because GDOT employs a placeholder domain as a root domain, which contains only enterprise Admin accounts. GDOT replaced the Windows NT resource domains with OUs. Consider the simplicity of the new domain model. Note also that GDOT has migrated now to Windows Server 2003 without modifying its AD structure. Figure 5.7. GDOT's Windows NT multimaster domain structure. Figure 5.8. GDOT's Windows 2000 and Windows Server 2003 domain structure. Originally designed for Windows 2000 and did not change for Windows Server 2003. A structure of this nature gives the simplistic advantage of a single domain with the flexibility of a multiple domain structure. However, even though the empty root + one or many child domain structure has often been implemented in the past, the rising security awareness of Microsoft and companies using these infrastructures (including HP) has taught us some clear disadvantages of this AD design. Companies that have not yet deployed AD in their enterprise should especially take the following drawbacks into consideration when deciding between creating multiple domains within their forest (including the empty root domain) or multiple single-domain forests if one single domain forest won't meet their needs:

Forest StructureJust as there are business and technical reasons for creating a single- or multiple-domain forest, there are also reasons to create a single- or multiple-forest AD infrastructure enterprise. Some say AD domains are security boundaries just like they were in Windows NT, and in a very limited sense they are; for example, for defining password policies. However, it is well known today that the true security boundary is at the forest level. In the beginning of Windows 2000 deployments, there were few multiforest deployments. However, a number of multiforest environments exist today and there are good reasons to employ such a structure. It was noted in the discussion on domain design that you should start with a single domain and prove you need more. This rule is even more important in regard to designing the forests. Although there are many issues to consider in the single versus multiple domain debate, there are only a few when deciding whether you should use a multiple forest environment. It basically comes down to two issues: political and security. Microsoft defined the security issue with the following statement (from "Using the Organization Forest Domain Model" Web site article):

This statement describes the importance of trust in those who are domain Administrators and the important security rights they have in the forest. It also points out that if others in the organization do not trust a domain Administrator, it may be cause for creating a separate forest. One government official I talked to several years ago was configuring a test environment to prove he could control security of data in a single domain. Because the implementation of Windows 2000 involved several government departments, if he lost his case, it could mean the creation of about 20 forests. In addition to security reasons, there can be political, business, or even legal reasons to deploy a multiple-forest enterprise. In analyzing these reasons, perhaps it's easiest to outline the negative impact of multiple forests. The strongest arguments against a multiple forest deployment are administration and implementation of Exchange. A good example of resolving the multiple forest issue is demonstrated in an AD design project I was involved in. This was a fairly small company that included an autonomous business unit. One business unit, we'll call it ABC, had a legal requirement to be separated from the rest of the company. It seemed after the assessment, that the rest of the company could adopt a single domain in a forest. However, an engineering division had operated Windows NT domains independently of the IT department. The IT department managed the Windows NT environment for the rest of the company. The research division was lobbying for a multiple-forest environment to retain this autonomy, making an enterprise of three forests, all running on the same physical network. The IT Administrators, however, wanted only one additional forest in addition to the ABC forest. This discussion became very political, and my partner and I were asked to make a presentation to describe the pros and cons of a multiple-forest deployment. The reasons to have multiple forests include

When analyzing the reasons to deploy a multiple-forest structure, weigh the negative aspects associated with multiple forests, as noted in Table 5.2. Table 5.2. Comparison of Single and Multiple Forest Features

After presenting these issues to technical and managerial participants in the meeting, they kept pressing me to boil it down further. After reviewing their business and political environment, I decided it came down to two issues: the role of the Enterprise Admin and Exchange. Members of the enterprise Admins group cannot be locked out from any domain. This was a political concern because the research department Admins didn't trust the IT folks and vice-versa. They didn't want the other Admins in their data ”a basic issue of trust as Microsoft's statement previously cited notes. Exchange was an issue because the company, including the ABC business unit, wanted to appear as a single organization. All employees should have a "User@company.com" e-mail address. Because Exchange uses the GC as the Global Address List (GAL), you can't have an organization spanning forests without synchronizing AD objects between the forests. It is possible to accomplish this by giving users in multiple forests a single e-mail address by the use of Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP) forwarding, but synching up contacts, calendar, and free/busy information is a huge challenge. Gathering all the interested parties together, I presented these two issues as those that needed to be decided to resolve the question of whether the research department should have its own forest or simply an OU in the company's root domain. In regard to the enterprise Admin issue, it came to an issue of trust that should be controlled by company policy. Anyone who had enterprise Admin privilege should be required to abide by company policies that detail proper conduct and use of that authority. If they don't abide by that policy and if you can't control your employees, that's a management problem ”not Windows. I then had an Exchange expert ”Don Livengood, who authored Chapter 12 of this book ”explain what was involved in getting Exchange to work across three forests ”the administrative overhead and difficulty in keeping calendaring and free/busy data in sync. Recognizing e-mail functions as a mission-critical application, one Administrator said, "I think people wouldn't mind a power outage if they could get to their e-mail." This discussion ended in a decision to adopt a single forest, single domain for these organizations. The point is that making the right decision took identifying the reasons not to adopt a multiple forest enterprise, getting all the parties together to discuss it, and urging them to do what is best for the company. Although the company's reason for wanting multiple forests was to ensure division of administrative duties , this can be a reason for other enterprises not to go to multiple forests. This requires some fairly complex security group organization if you have Administrators who must have domain Admin or enterprise Admin rights in more than one forest. tip Windows Server 2003 makes multiforest enterprises much easier to manage with the addition of Kerberos-based, cross forest trusts. These trusts allow Administrators in one forest to grant very granular access to resources in another forest. note Microsoft has an excellent whitepaper entitled "Windows 2000/2003: Multiple Forests Considerations White Paper," available for download at http://www.microsoft.com/downloads/details.aspx?FamilyID=b717bfcd-6c1c-4af6-8b2c-b604e60067ba&DisplayLang=en (or go to http://www.microsoft.com/downloads and search for "multiple forest"). OU StructureThe OU, of course, is an excellent alternative to multiple domains. Microsoft recommends using OUs to create directory partition structures for changeable entities. For instance, rather than making domains for Engineering, HR, Executive, Finance, and Program offices, OUs are a better solution because these names can change. Figure 5.9 compares a domain-based and an OU-based implementation. Although Windows Server 2003 has Domain Rename capability, it isn't trivial and there are still a lot of unresolved issues concerning application support. Building OUs allows not only flexibility of rename and restructure, but also requires no additional hardware for new DCs. Also, moving objects between OUs is much easier than between domains. Movement of users across domains requires tools such as Microsoft's Active Directory Migration Tool (ADMT), LDIFDE, or movetree .exe. Movement between OUs can be done in the AD Users and Computers GUI (Graphical User Interface). Figure 5.9. Comparing a domain-based structure to an OU-based structure. tip In Windows Server 2003, you can select multiple objects (such as users) and drag and drop them onto another OU. In designing an OU structure, although there are no real design rules, some best practices have been developed from experienced AD designers. The structure really is determined by whether your focus is on Group Policy or administration. Most likely, you will need to consider both in your own design. Group Policy-Based OUsOne common structure (and similar to that used by HP) that you might consider using is to divide up the first-level OU structure into users and computers. This is a Group Policy-based approach. Because policy is partitioned into user and computer settings, and you can actually limit a Group Policy Object (GPO) to apply only computer or user settings, OUs divided in this way make sense. Figure 5.10 shows an example of how a three- tier OU structure based on policy might be structured. Note that the first level has OUs titled Servers, Workstations, Printers, and Users. The second level further divides users into Sales, Manufacturing, Engineering, and IT staff. The second level under the Servers OU includes File/Print, Systems Management Services (SMS), and DHCP/WINS (Windows Internet Name Service). Similarly, you could subdivide the printers and workstations OUs, or leave them as single-level OUs. The Manufacturing OU contains a third-level OU structure that divides the Manufacturing users into geographies of North and South America and Canada. This demonstrates the flexibility of the OU structure. Some OUs need be only one level deep, some can be two, and others three or more. Figure 5.10. A three-tier Group Policy-based OU structure built for Group Policy deployment as a critical design factor. Administration-Based OUsAn administration-based OU's model is primarily based on the requirements of a company for the delegation of administrative rights. The structure would look something like that shown in Figure 5.11. This is almost the reverse of the Group Policy-based structure. Here, you have the geography-based OUs at the top of the structure, the computer- and user-based OUs at the second level, and the subdivisions of those OUs (such as that shown for the Servers OU) on the third level. Obviously this would work if your Administrators were organized by geography. If organized by business unit, you could replace the geography OUs with business unit names. Figure 5.11. An administration-based OU structure, placing emphasis on administration of the overall domain components. In working with the Qtest Windows 2000 testing environment at HP (originally created at Compaq), I decided to create an OU structure for the QAmericas domain and struggled through several designs. During this exercise, I decided that the most important thing in this environment was administration. Administrators were scattered throughout North and South America. I needed an OU structure that was conducive to permitting Administrators to get to all resources in their geography. Imagine the nightmare if I used the Group Policy-based structure. My Administrators' accounts would reside in the geographies ”the third tier in the structure. But there would potentially be more geography-based OUs at that level requiring some interesting delegation so that each South American Admin could manage South American resources. However, if I apply the administration-based structure shown in Figure 5.11, all the South American resources are under the South America OU. I can put the South American Admin accounts in that OU, or perhaps put them in a child OU, and delegate rights appropri ately. It's really amazing as you look at different structures and review your business needs, how the solution eventually presents itself to you. OU DepthThe depth of the OU tree is really governed only by the Group Policy structure that affects logon performance and what you can live with. Microsoft published data for Windows 2000 that specified that each GPO applied to a user-generated 58K, and each GPO applied to a computer-generated 72K of traffic. On startup and logon, each policy is copied from the DC to the workstation. Thus, the more policies that apply to the user, the longer it takes to log on. Note that a user is penalized only for the GPOs that apply to the user ”not the total GPOs defined in the domain. This is actually predictable. The Traffic Calculator that is available on the Web site for this book (www.phptr.com/title/0131467581) has all the built-in formulas for calculating this impact. (The instructions for using it are on the first worksheet.) Note that the number of groups a user or computer is a member of also impacts the logon and startup time. A good example of an OU design exercise was a large, global enterprise based in Atlanta that had already determined that its OU structure was to be six levels deep when I was asked to review the design. The interesting thing was that all of the objects ”users, computers, printers, and so on ”were in the sixth -level OU. The other OU levels contained only groups and were designed to look like the business organization. Concerned about this, I convinced my coworkers that we should review the structure. We locked ourselves in a conference room for about three hours one day and drew all possible OU structures ”basically iterations of the Group Policy- and administration-based structures discussed in this section previously. As we drew the structures on the whiteboard, we tried to fit the company's administration model into them. Finally it was evident that the only way to meet the business needs of the administration model the company wanted was to implement the six-layer OU model. I was satisfied with that because we challenged the model and proved it was the best solution. Note that if we had taken the rule of thumb of not going more than three levels deep, we would not have arrived at the best solution. In addition, this six-level structure didn't impact the logon performance more than if it had been a single-level structure because the number of GPOs would be the same. If you want to reduce the logon time, you reduce the GPOs or groups, not the OUs. Default and Special-Purpose OUsBy default, one OU is created during AD installation: the DC's OU. This OU, by default, houses all DCs and contains a Default Domain Controller (DDC) GPO. Although you can move DCs to any OU you want to, I don't recommend it. DC security policy is really in its own world, even by Microsoft's standards. Moving DCs out of the DDC's OU and changing the DDC's policy is adding a degree of uncertainty to the environment. If you run into security issues in the future, you should first ask whether it's because the DCs are not in the DDC OU. There might be valid reasons to do this, but make sure it's critical enough to pay the potential price. note The users and computers containers under the domain container are just that ”containers ”not OUs. In Windows 2003, you can convert these containers into OUs so that Group Policy can apply to them. Special-purpose OUs are used to house objects temporarily during an installation or as a staging area for migration. They also can be used to troubleshoot problems such as group membership or Group Policy application. For instance, they can be used to synchronize objects in the AD for legacy e-mail environments such as Exchange 5.5 and GroupWise. Temporary OUs can be used to house the synchronized mailbox user contacts. Naming StandardsNaming AD components is entirely up to the architect. Windows doesn't really care what you name anything as long as most objects have a unique name within the domain or the forest. The name uniqueness is especially important when migrating multiple Windows NT domains into a single AD domain or fewer AD domains; there can only be one group called Sales and only one computer account called PC1. Also NetBIOS has the 15-character limit and DNS names in Windows 2000 are limited to 64 characters including the dot (".") delimiters. However, naming standards from a design and troubleshooting perspective is important. This section discusses suggested naming strategies for various objects. Defining a standard naming practice allows for growth in the eventuality of a merger, acquisition, or expansion of the business without throwing the AD into disarray. Naming standards are especially true in troubleshooting. No matter how well you design the AD, something will break and you'll be on the phone with Microsoft or HP or someone who will need to understand your environment. When you start listing names like Skywalker, Yoda, Darth, and HanSolo, you will not only be a little embarrassed, but the poor support person on the other end of the line will have a hard time telling whether Yoda is in Atlanta or Singapore and whether it's a GC or an application server, even if he knows that Skywalker is in Los Angeles. Besides, from a pure security standpoint, it's best to name your servers without a special naming convention that could lead a hacker to the best server to attack in the enterprise. However, when you start to increase the number of servers, and run out of Star Wars characters, what will you do? General StandardsDetermine the general standards that will be employed in names. These standards can include things like the length of names, inclusion of special characters, and how naming standards can be modified. Domain NamespaceIf you are in a Windows NT 4.0 environment, determining the actual namespace is a big deal. Microsoft refers to naming the domain namespace as an "irreversible decision," meaning once you establish the name of a domain, you can't change it without tearing it down and starting over. Windows Server 2003 allows domains to be renamed, but as discussed previously in this chapter and in Chapter 1, it's not trivial, and due to dependencies on the domain name by applications, might not even be possible. As of this writing, Exchange Server 2003 SP1 was just released and supports Domain Rename, but at this time there aren't any known organizations that have renamed a domain with Exchange, other than Microsoft. You must choose an appropriate name for the Windows 2000 or 2003 domain that will be the root of your domain tree. For Windows NT 4.0 environments, you probably already have a public domain name that hosts an external Web site and supplies your e-mail address identification, such as HP.com or Microsoft.com. However, selecting the internal Windows domain name presents some interesting challenges, such as whether you will use the same namespace for internal as well as external use. For example, Compaq used Compaq.com for the external space (e-mail, external Web site, and so on) and Cpqcorp.net for the internal namespace. note Although it is beyond the scope of this book to include the pros and cons of each method, note that Compaq and Microsoft elected to use different names, whereas HP uses HP.com internally and externally. Using different names makes life easier. Microsoft's "DNS" whitepapers have some good information on how to deal with this issue (see http://www.microsoft.com/dns). Problems with the domain namespace can arise if you are part of a larger parent company that has not migrated to Windows Server 2003 yet. For example, a county attorney's office we were working with was actually controlled by the county's IT department, and the county attorney's office only had a staff of three people for IT support. The attorney's office wanted to migrate to Windows 2000, but the rest of the county offices were either at Windows NT 4.0 or using Netware or UNIX environments. The problem with choosing the name early is that when the county goes to Windows 2000, and it chooses a different name, the attorney's office will have to migrate to the new structure. Our recommendation was to talk to the IT manager and determine what the root name would be if the county goes to Windows 2000. Because the county already had a root DNS name for its UNIX infrastructure, it would probably be that name. After the attorney's office determined that name, it could take two servers, promote them to create the county root domain (remember you never want to do fewer than two DCs for redundancy), create the county attorney's office domain as a child to the county root, and then build everything off of that. Figure 5.12 depicts the expansion under this configuration. Figure 5.12. Using an empty root domain allows the county to expand in the future, and permits the attorney's office to implement a migration immediately without repercussion in the domain structure. When the county decides to implement Windows 2000, it simply joins its servers to the root domain already established and demotes the DCs in the attorney's office if desired. The county attorney domain can continue uninterrupted, and other county offices can join as separate domains. In case they adopt a single domain for the county with OUs for each county department, the county attorney's office would need to migrate from the domain to the OU, which would be fairly easy because it would be an intra-forest migration. The problem, of course, is that the IT department could decide to use a different name when actually creating the Windows Server 2003 environment. However, Windows Server 2003 would add additional flexibility by allowing the county to rename that root domain. tip Windows Server 2003 removes a lot of the fear of naming domains and forests with the Domain Rename feature. Microsoft refers to this as "removing irreversible decisions." However, Domain Rename is complex and has restrictions that might prevent you from using it in your infrastructure, so you still need to plan carefully . Refer to the section "Domain Rename" in Chapter 1 of this book for details on how domain rename works. Microsoft provides two excellent whitepapers on Domain Rename at http://www.microsoft.com/windowsserver2003/downloads/domainrename.mspx. Security PrincipalsSecurity principals are defined as users, computers, and groups. These objects usually have names associated with actual names (for users) or with descriptive functions. For instance, a user object might have the user's actual name ”for example, Tyler Olsen ”whereas a group might be labeled HRAdmins to describe the usage. On the other hand, other objects, such as servers and printers, contain location information such as site or domain affiliation . You can determine these names in a variety of ways. Some options to consider are noted here:

Group PolicyDesigning Group Policy could fill a whole book by itself, and, in fact, has. My good friend and Group Policy expert, Jeremy Moskowitz, authored a book called Windows 2000 Group Policy, Profiles and IntelliMirror (Sybex, 2001), which I keep near my computer as a handy reference. Jeremy recently authored a second Group Policy book, Group Policy, Profiles and IntelliMirror for Windows 2003, Windows 2000, and WIndows XP (Sybex, 2004) that deals with Windows Server 2003 features. Jeremy also offers a Web site that hosts newsgroups specifically dedicated to Group Policy issues at http://www.moskowitz-inc.com. Space limits the discussion here, and again, my goal is to give you design tips rather than educate you on Group Policy. Having worked for the past four years troubleshooting probably hundreds of Group Policy problems, I'll take the perspective of listing best practices and observations, with a few actual examples thrown in. Let's first list important design criteria that you need to keep in mind when defining Group Policy standards, followed by Group Policy tips, and finally a list of important Group Policy additions for Windows Server 2003 and Windows XP. note Windows 2000 Group Policy had approximately 700 settings. Windows Server 2003 added nearly 200 additional settings. Windows XP also added a number of settings. It is important to design Group Policy and understand the impact of these settings before you deploy them, by testing. Many options that were only exposed as Registry hacks in Windows 2000 are now easy-to-find Group Policy settings in Windows Server 2003, increasing the probability for error if you aren't careful. Group Policy DesignGroup Policy must be designed and planned. This book's Web site at www.phptr.com/title/0131467581 contains a spreadsheet with all Group Policy settings for Windows 2000 and another for Windows Server 2003. Several worksheets in each file correspond to sections of policy such as Security Settings, Administrative Templates, and so on. The worksheets contain all settings listed separately on each row. You can add the names of your GPOs in columns to the right of the setting name, and then enter "enabled" or "disabled"for each setting in each GPO. This takes considerable time on the front end and to maintain, but it will be worth the effort when you want to change something later on, or need to troubleshoot a problem. Rather than wading through the user interface (UI), you can get the information from the spreadsheet. Windows Server 2003 supports a tool called the Group Policy Management Console (GPMC), which reports all the current settings, but doesn't save them in a nice tabular form like the spreadsheet. My recommendation is to use both GPMC and the spreadsheet. Group Policy applies only to the user or computer where the account actually exists. A common mistake is to think that Group Policies apply to groups; however, a group can be used to set permissions on a Group Policy so that it applies only to users of a group. For instance, Figure 5.16 shows user Russ, who is a member of the OfficeAdmins group. Russ' user account is in the Marketing OU, which has the MKTGDesktopGPO linked to it, whereas the OfficeAdmins group is in the AppAdmin OU. The GPOs that will be applied are Default Domain Policy and MKTGDesktopGPO. The OfficeAdmin GPO (if linked to this OU) is not applied. This is a basic rule that has existed since the birth of Windows 2000, but many Admins either don't understand it or have forgotten how it is applied. Figure 5.16. GPO is applied to the OU where the user or computer account exists. It is not applied to members of groups within an OU. When designing your GPO strategy, make sure you understand this principal. It's a good idea to make a chart like that shown in Table 5.3, for tracking GPOs. Identify the function of the policy and whom it applies to, and then identify the domain or OU that those security principals live in. Table 5.3. GPO Application Table

tip You might find as you analyze GPO application, that it affects the OU structure. You might see more logical groupings of users and computers when you define GPOs that apply to them, which affects the OU structure. This is part of the design process ”make sure it all fits. Group Policy Features and LimitationsA number of Group Policy features actually impose limitations on the design. Several important features are described here. Take the time to understand their implications in your environment and design the Group Policy deployment accordingly . Multiple Instances of GPOsYou can link a GPO to multiple OUs if needed, but for performance reasons, you shouldn't link GPOs across domains if your forest has multiple domains. In essence, you are building a GPO library in the AD (per domain) and then you can link them to appropriate OUs. GPO FunctionsAs was noted previously, user logon time is directly affected by the number of GPOs that apply to the user, and the computer startup time is affected by GPOs that apply to the computer. Figure 5.17 shows Microsoft's figures regarding traffic in Kbps generated by the number of GPOs applied to the user. Figure 5.17. Performance during client startup (boot) and logon process is related to the number of GPOs applied to the computer and the user accounts. Note that network traffic increases only slightly as the number of GPOs increases . For example, one GPO (including computer startup and user logon) generated 102Kbps; five GPOs generate 130Kbps and ten GPOs generate only 155Kbps. Considering just user logon performance, you can apply only one or two GPOs containing all settings that you need to configure for the users. However, this makes the GPOs more complex, and more difficult to manage and troubleshoot. It is now a very common and recommended practice to define a number of simple, yet focused GPOs, apply them as needed, and take the hit on performance. Using the numbers in the chart in Figure 5.17, you can see that there is no difference between having one and five GPOs applied and only 25Kbps per user if you go up to ten. This is miniscule in comparison to the time that will be spent managing and troubleshooting one or two giant policies. Using the Traffic Calculator on this book's Web site at www.phptr.com/title/0131467581, you can easily calculate the impact. Using the example in Table 5.3, the UserScripts1 GPO is applied to the users in Finance and HR OUs. Thus, we store a single GPO and create links to multiple GPOs. Note also that the Finance OU has DesktopL2 as well as UserScripts1 GPOs applied. The alternative, of course, would require us to combine the settings of DesktopL2 and UserScripts1 into a single GPO and apply it to Finance. Because the MKTG OU needs DesktopL2 and UserScripts2, another GPO would have to be created for MKTG OU. Splitting the GPOs up into smaller functions makes them more flexible. Also, if an error occurs in the logon script, you only have to debug the script's GPO and you don't have to deal with desktop settings. The important thing here is to define the function of each GPO and define which domain(s) and OUs they should apply to. Account Security SettingsThe account security settings, including Password Policy, Account Lockout Policy, and Kerberos Policy, can only be applied at the domain level. Thus, you can have only one Password Age Setting for the entire domain, rather than allowing each OU to dictate this setting to its users. DCs, however, behave differently in applying security, as explained in the "Account Security" section later in this chapter. tip Account security settings (such as Password Length) can be defined in a GPO at the OU level; however, they will never apply. Track GPO SettingsThere is a GPO design spreadsheet on this book's Web site at www.phptr.com/title/0131467581 that lists all GPO settings for Windows Server 2003. I have used columns to the right of the setting label and indicated which GPO uses that setting and what the setting is. A simplistic example is shown in Table 5.4. You can see from Table 5.4 that defining each setting for each GPO could be prohibitive in a large enterprise with many GPOs, each having potential for nearly a thousand settings. Some organizations have a staff of several Administrators that does nothing but administer GPOs. This is usually a political requirement in which organizations want their own GPO control, but it's a poor administration model. It's difficult to troubleshoot problems with so many Admins making changes, and multiple people trying to solve the problem. Table 5.4. GPO Tracking Table

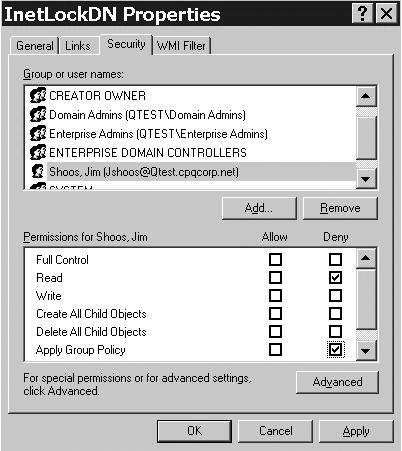

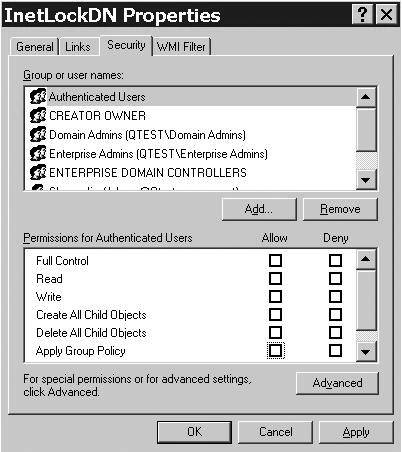

GPO FilteringGPO filtering is available in Windows Server 2003 just as it was in Windows 2000. GPO filtering allows the Administrator to restrict a GPO from applying to certain users, computers, or groups. For instance, suppose you have a policy applied to an OU that prevents users from accessing the Internet, called InetLockDn Policy. However, there are five users in that OU that need Internet access. Rather than creating a separate OU for those users, you could simply define a filter so that the policy doesn't apply to those five users. This is done from the Group Policy Editor by selecting the Properties button, and then choosing the Security tab in the policies properties page. Figure 5.18 shows that we have filtered user Jim Shoos by denying Read and Apply Group Policy rights. In this case, authenticated users still have Read and Apply Group Policy permissions. Thus, the policy applies to all authenticated users except Jim Shoos. Note that we could do the reverse and have the policy apply to only a user or group. Figures 5.19 and 5.20 demonstrate this. Figure 5.19 shows that we had to set the authenticated users group to not have Read or Apply Group Policy rights, which means no one will get the policy applied. Then, as shown in Figure 5.20, we give the rights to the user (Jim Shoos in this case). If you don't remove Read and Apply Group Policy from authenticated users, then all users will have the policy applied to them. Figure 5.18. Filtering a GPO to prevent it from applying to a user. Figure 5.19. Filtering step 1 ”Removing Read and Apply Group Policy rights from the authenticated users group so the policy applies to no one. Figure 5.20. Filtering step 2 ”Adding Read and Apply Group Policy rights to a user so the GPO will apply only to that user. tip Don't deny access to authenticated users. Because this will be evaluated to provide the most restrictive access, it will prevent any authenticated user from getting the GPO, including the user you want to grant access to. Rather, clear the Read and Apply Group Policy rights to prevent GPO access. Filtering takes considerable additional processing time to enumerate the Access Control Lists (ACLs) and affects user logon performance. If you have to filter a large number of users from getting a GPO, it might make sense to create a separate OU. Be sure to test the performance hit that users will have if you use filtering. WMI (Windows Management Instrumentation) FilteringWindows Server 2003 and the GPMC provide new capabilities for customizing queries using WMI, including the WMIC interface and the WMI filters in Group Policy. The GPMC is described later in this section, whereas WMI is covered in detail in Chapter 10, "System Administration." The WMI filter in Group Policy basically uses the WMI Query Language (WQL) to allow a WMI query (filter) to be applied from within a policy, and determines whether to apply the GPO to a target computer based on that computer's attributes. This is a much more powerful option than simple security filtering offered in Windows 2000. WMI filtering is detailed in Chapter 10, in the "Windows Management Instrumentation (WMI)" section. A single filter can contain multiple queries to be evaluated against the WMI repository of the target computer. If the evaluation of all queries in the filter is determined to be FALSE, the GPO is not applied; if they are TRUE, the GPO is applied. Important features and functionality of WMI filtering in Group Policy include

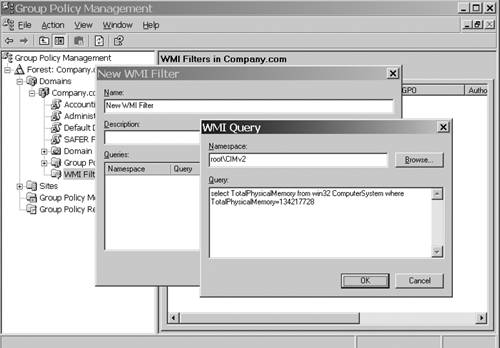

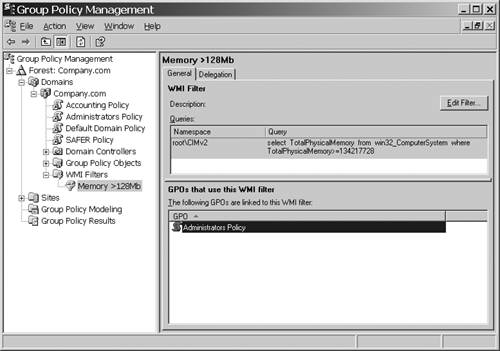

The following WMI filter checks to see whether the physical memory of the computer is greater than 128MB, and if so, the GPO will be applied: Select TotalPhysicalMemory from win32_ComputerSystem where TotalPhysicalMemory >= 134217728 Using the GPMC, you can define the WMI filter and associate it with a GPOas follows :

note If the WMI Filters folder is not available, you are running the GPMC tool in a Windows 2000 domain that has not had ADPrep/ForestPrep run in it.

warning Remember, you can apply only one WMI filter to a single GPO, but you can link a single WMI filter to multiple GPOs.

You've created a WMI filter on the accounting policy (in the example in the figures) so that this policy only applies to computers that have greater than or equal to 128MB memory. This is similar to the security filtering we did in Windows 2000, in which we could apply or deny a policy only to certain users or groups. It is critical that you understand there is a price to be paid for WMI filters. Microsoft is very emphatic about the fact that WMI filters should be used sparingly, preferably when the policy in question has a specific lifetime. In addition, evaluating WMI filters can significantly add to the amount of time needed to apply and process policy. These filters also add considerable complexity. Besides the normal Group Policy processing issues like block inheritance, no override, ACL filtering and so forth, now you must contend with WMI filters added to the mix. It is also important to note that since Windows 2000 clients can't ever apply WMI filters, any Windows 2000 clients that receive the policy will always return TRUE when evaluating a WMI query. That is the GPO containing a WMI filter will always apply to Windows 2000 clients . In terms of troubleshooting, note that the new GPResult.exe and the Group Policy Results option in the GPMC (both give the same information) provide an excellent list of filters that are applied. Since WMI filters are new to Windows Server 2003, and because many administrators typically aren't skilled in using WMI, I asked Microsoft for some details on how to use WMI filters and some sample filters. Tim Thompson graciously offered the following examples and description.

note For further Information on WMI filters, see the Distributed Services Guide of the Windows Server 2003 Resource Kit. Also A number of sample WMI queries are available at http://www.microsoft.com/downloads/details.aspx?FamilyId=D26E88BC-D445-4E8F-AA4E-B9C27061F7CA&displaylang=en. XP Settings in Windows 2000Windows XP came with a new set of Group Policy settings that Windows 2000 did not have. Microsoft KB article 314953 "HOW TO User Group Policy to Deploy Windows XP in a Windows 2000-Based Network" describes these settings and the process used to incorporate them in Windows 2000. Essentially, you bring an XP client into the domain, and then edit the local Group Policy, which allows you to upload the XP policy settings to a DC of your choosing in the domain (it provides a browse list of DCs). The settings are then uploaded to the DC and appear when you open a Group Policy Editor in that domain. Note however, that these settings only apply to XP clients; they don't affect Windows 2000 Professional clients. This process of adding the XP settings into the domain's policy settings allows XP settings to be managed with other GPO settings in the domain context. These new XP settings are included in Windows Server 2003 without requiring this process to add them. Group Policy ToolsMicrosoft has made some significant improvements in Group Policy management tools, including GPResult, a command-line utility that has been considerably enhanced in Windows Server 2003, and the GPMC, available for download from Microsoft. GPResult ToolWindows 2003 and XP provide a new version of the GPResult tool. GPResult provides a client-side view of the policies that were applied to the computer and the user. Part of the Windows 2000 Resource Kit, GPResult is built-in to XP and Windows Server 2003. The tool provides excellent information not available in the Windows 2000 version including

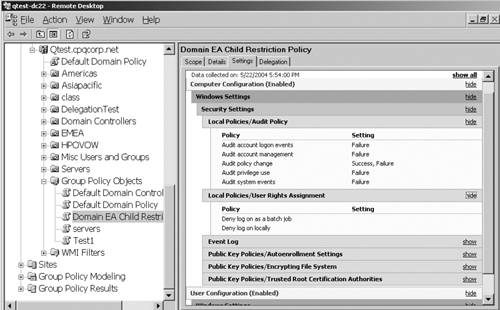

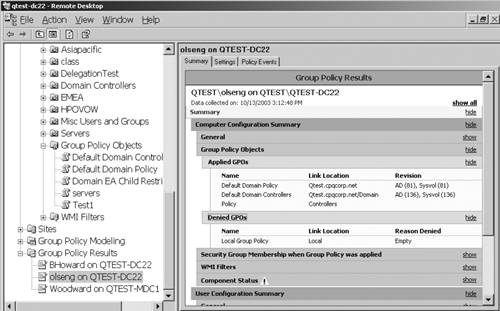

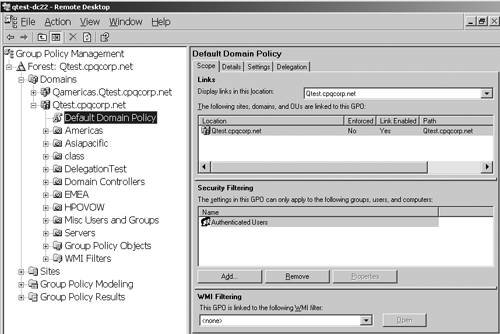

This version of GPResult can be used in a Windows 2000 domain, but must be run from an XP client or Windows Server 2003 server in that domain. This tool is so valuable for troubleshooting, I actually made one customer buy XP just so I could use the new version of GPResult and shorten the diagnosis time. It really helped. Group Policy Management Console (GPMC)Microsoft has also given us another great tool called the GPMC. GPMC is a GUI-based tool available for download from Microsoft at http://www.microsoft.com/downloads/details.aspx?FamilyId=C355B04F-50CE-42C7-A401-30BE1EF647EA&displaylang=en. This tool allows management and troubleshooting of all GPOs in all domains in a forest. Figure 5.23, for example, shows management for two domains: Qamericas.qtest.cpqcorp.net (top) and Qtest.cpqcorp.net (bottom). Note the left-hand pane shows domains and OUs, and there is also a Group Policy Objects folder for each domain. I have selected the Group Policy Objects folder in the Qtest domain, and all GPOs defined for the domain are listed on the right-hand pane. Windows 2000 required multiple snap-ins to manage GPOs in multiple domains and OUs. Figure 5.23. GPMC permits management of the Qtest.cpqcorp.net parent domain and the Qamericas.Qtest.cpqcorp.net child domain. The GPMC can be used to see the policy settings that are applied to a user or computer. Although it doesn't track the settings like the spreadsheet does, it allows you to see effective settings in an easy-to-use console. Other important features of the GPMC tool include

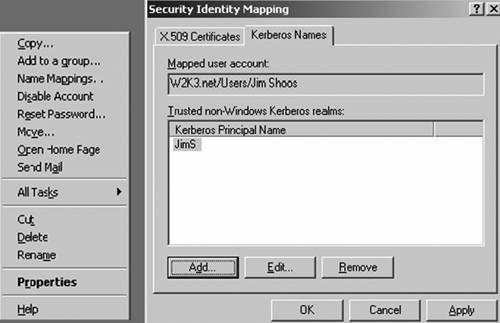

Furthermore, a major benefit of GPMC is that it allows the Administrator to back up and restore GPOs in a forest or even in a multiforest environment. Without using GPMC, acci dentally deleted or badly misconfigured GPOs would otherwise have to be manually re-created or recovered via a complex SYSVOL restore. You can see that GPMC is a very powerful tool. Considerable documentation is available from Microsoft. The easiest way to find it is to go to the "Enterprise Management with the Group Policy Management Console" Web page at http://www.microsoft.com/windowsserver2003/gpmc/default.mspx#XSLTfullModule122121120120, or simply search for "GPMC" on the Microsoft Web site. Trust DefinitionsTrusts to external forests, Windows NT domains, or Kerberos realms should be defined in the design document. Windows 2000, supporting only NTLM type external trusts, required individual trusts to be created between all domains in separate forests because NTLM didn't provide transitivity. Figure 5.27 shows two Windows 2000 forests, each with three domains. To get a "complete trust model," trusts were required between every two domains, as shown in Figure 5.27, similar to what the trust model in Windows NT 4.0 would look like. Obviously, this is very confusing and difficult to administer. Creating a trust across root domains would not provide the same transitivity as if they were in the same forest. Figure 5.27. Windows 2000 used NTLM trusts to trust domains in different forests. Note that Windows Server 2003, on the other hand, supports Kerberos cross forest trusts, which allow a single trust to be created at the root level and maintain transitivity to child domains. Figure 5.28 illustrates this. You can administer a multiple forest enterprise very easily with this type of trust because there is only a single trust (it can be two-way) to maintain, and the Administrator can choose authentication options noted in the cross forest trust section in the "Security" section of Chapter 1. Figure 5.28. Windows Server 2003 provides Kerberos trusts between forests. In a Windows Server 2003 forest, you also can create a trust to an MIT Kerberos v5 realm, allowing realm principals to access Windows resources and vice-versa. This is accomplished by providing name mapping . Because the MIT principal has no knowledge of Security Identifiers (SIDs) and Windows requires them, a user account is created in the Windows domain and is mapped to the realm principal. Name mapping is an attribute of the user object. In the Users and Computers Snap-in, turn on Advanced Features in the View menu, and then right-click the user account. The Name Mapping dialog box appears as shown in Figure 5.29. Figure 5.29. Mapping a Windows Server 2003 user account to a Kerberos realm principal name. Identify all such trusts in the design document. Just like the GPO design affecting the OU structure, familiarity with the Kerberos trust might influence your decision on deploying multiple forests. |

| < Day Day Up > |

EAN: N/A

Pages: 214