Organizational change

OVERVIEW

This chapter tackles the issue of organizational change. How does the process of organizational change happen? Must change be initiated and driven through by one strong individual? Or can it be planned collectively by a powerful group of people, and by sheer momentum, the change will happen? Perhaps there is a more intellectual approach that can be taken. Are there payoffs to understanding the whole system, determining how to change it, and predicting where resistance will occur? On the other hand, maybe change cannot be planned at all. Something unpredictable could spark a change, which then spreads in a natural way.

This chapter addresses the topic of organizational change in three sections:

- how organizations really work;

- models and approaches to organizational change;

- summary and conclusions.

In the first section we look at assumptions about how organizations work in terms of the metaphors that are most regularly used to describe them. This is an important starting point for those who are serious about organizational change. Once you become aware of the range of assumptions that shape people’s attitudes to and understanding of organizations, you can take advantage of the possibilities of other ways of looking at things, and you can begin to understand how other people in your organization may view the world. You can also begin to see the limitations of each mindset and the disadvantages of taking a one-dimensional approach to organizational change.

In the second section, we set out a range of useful models and ideas developed by some of the most significant writers on organizational change. This section aims to illustrate the variety of ways in which you can view the process of organizational change. We also make sense of the different models and approaches by identifying the assumptions underpinning each one. When you understand the assumptions behind a model, you can start to see its benefits and limitations.

In the third section, we come to some conclusions about organizational change, and stress the importance of being aware of underlying assumptions and having the flexibility to employ a range of different approaches.

HOW ORGANIZATIONS REALLY WORK

We all have our own assumptions about how organizations work, developed through a combination of experience and education. The use of metaphor is an important way in which we express these assumptions. Some people talk about organizations as if they were machines. This metaphor leads to talk of organizational structures, job design and process reengineering. Others describe organizations as political systems. They describe the organization as a seething web of political intrigue where coalitions are formed and power rules supreme. They talk about hidden agendas, opposing factions and political manoeuvring.

Gareth Morgan’s (1986) work on organizational metaphors is a good starting point for understanding the different beliefs and assumptions about change that exist. He says:

Metaphor gives us the opportunity to stretch our thinking and deepen our understanding, thereby allowing us to see things in new ways and act in new ways… Metaphor always creates distortions too… We have to accept that any theory or perspective that we bring to the study of organization and management, while capable of creating valuable insights, is also incomplete, biased, and potentially misleading.

Morgan identifies eight organizational metaphors:

- machines;

- organisms;

- brains;

- cultures;

- political systems;

- psychic prisons;

- flux and transformation.

We have selected four of Morgan’s organizational metaphors to explore the range of assumptions that exists about how organizational change works. These are the four that we see in use most often by managers, writers and consultants, and that appear to us to provide the most useful insights into the process of organizational change. These are:

- organizations as machines;

- organizations as political systems;

- organizations as organisms;

- organizations as flux and transformation.

Descriptions of these different organizational metaphors appear below. See also Table 3.1 which sets out how change might be approached using the four different metaphors. In reality most organizations use combinations of approaches to tackle organizational change, but it is useful to pull the metaphors apart to see the difference in the activities resulting from different ways of thinking.

|

Metaphor |

How change is tackled |

Who is responsible |

Guiding principles |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Machine |

Senior managers define targets and timescale. Consultants advise on techniques. Change programme is rolled out from the top down. Training is given to bridge behaviour gap. |

Senior management |

Change must be driven. Resistance can be managed. Targets set at the start of the process define the direction. |

|

Political system |

A powerful group of individuals builds a new coalition with new guiding principles. There are debates, manoeuverings and negotiations which eventually leads to the new coalition either winning or losing. Change then ensues as new people are in power with new views and new ways of allocating scarce resources. Those around them position themselves to be winners rather than losers. |

Those with power |

There will be winners and losers. Change requires new coalitions and new negotiations. |

|

Organisms |

There is first a research phase where data is gathered on the relevant issue (customer feedback, employee survey etc). Next the data is presented to those responsible for making changes. There is discussion about what the data means, and then wh A solution is collaboratively designed and moved towards, with maximum participation. Training and support are given to those who need to make significant changes. |

Business improvement/HR/OD managers |

There must be participation and involvement, and an awareness of the need for change. The change is collaboratively designed as a response to changes in the environment. People need to be supported through change. |

|

Flux and transformation |

The initial spark of change is an emerging topic. This is a topic that is starting to appear on everyone’s agenda, or is being talked about over coffee. Someone with authority takes the initiative to create a discussion forum. The discussion is initially fairly unstructured, but well facilitated. Questions asked might be ‘Why have you come?’, ‘What is the real issue?’, ‘How would we like things to be?’ The discussion involves anyone who has the energy to be interested. A plan for how to handle the issue emerges from a series of discussions. More people are brought into the net. |

Someone with authority to act |

Change cannot be managed; it emerges. Conflict and tension give rise to change. Managers are part of the process. Their job is to highlight gaps and contradictions. |

|

Gareth Morgan’s metaphors used with permission of Sage Publications Inc. |

|||

MACHINE METAPHOR?

The new organizational structure represents an injection of fresh skills into the Marketing Function.

Fred Smart will now head up the implementation of the Marketing Plan which details specific investment in marketing skills training and IT systems. We intend to fill the identified skills gaps and to upgrade our customer databases and market intelligence databank. A focus on following correct marketing procedures will ensure consistent delivery of well targeted brochures and advertising campaigns.

MD, Engineering Company

Organizations as machines

The machine metaphor is a well-used metaphor which is worth revisiting to examine its implications for organizational change. Gareth Morgan says, ‘When we think of organizations as machines, we begin to see them as rational enterprises designed and structured to achieve predetermined ends.’ This picture of an organization implies routine operations, well-defined structure and job roles, and efficient working inside and between the working parts of the machine (the functional areas). Procedures and standards are clearly defined, and are expected to be adhered to.

Many of the principles behind this mode of organizing are deeply ingrained in our assumptions about how organizations should work. This links closely into behaviourist views of change and learning (see description of behavioural approach to change in Chapter 1).

The key beliefs are:

- Each employee should have only one line manager.

- Labour should be divided into specific roles.

- Each individual should be managed by objectives.

- Teams represent no more than the summation of individual efforts.

- Management should control and there should be employee discipline.

This leads to the following assumptions about organizational change:

- The organization can be changed to an agreed end state by those in positions of authority.

- There will be resistance, and this needs to be managed.

- Change can be executed well if it is well planned and well controlled.

What are the limitations of this metaphor? The mechanistic view leads managers to design and run the organization as if it were a machine. This approach works well in stable situations, but when the need for a significant change arises, this will be seen and experienced by employees as a major overhaul which is usually highly disruptive and therefore encounters resistance. Change when approached with these assumptions is therefore hard work. It will necessitate strong management action, inspirational vision, and control from the top down.

See the works of Frederick Taylor and Henri Fayol if you wish to examine further some of the original thinking behind this metaphor.

Organizations as political systems

When we see organizations as political systems we are drawing clear parallels between how organizations are run and systems of political rule. We may refer to ‘democracies’, ‘autocracy’ or even ‘anarchy’ to describe what is going on in a particular organization. Here we are describing the style of power rule employed in that organization.

The political metaphor is useful because it recognizes the important role that power play, competing interests and conflict have in organizational life. Gareth Morgan comments, ‘Many people hold the belief that business and politics should be kept apart… But the person advocating the case of employee rights or industrial democracy is not introducing a political issue so much as arguing for a different approach to a situation that is already political.’

The key beliefs are:

- You can’t stay out of organizational politics. You’re already in it.

- Building support for your approach is essential if you want to make anything happen.

- You need to know who is powerful, and who they are close to.

- There is an important political map which overrides the published organizational structure.

- Coalitions between individuals are more important than work teams.

- The most important decisions in an organization concern the allocation of scarce resources, that is, who gets what, and these are reached through bargaining, negotiating and vying for position.

This leads to the following assumptions about organizational change:

- The change will not work unless it’s supported by a powerful person.

- The wider the support for this change the better.

- It is important to understand the political map, and to understand who will be winners and losers as a result of this change.

- Positive strategies include creating new coalitions and renegotiating issues.

What are the limitations of this metaphor? The disadvantage of using this metaphor to the exclusion of others is that it can lead to the potentially unnecessary development of complex Machiavellian strategies, with an assumption that in any organizational endeavour, there are always winners and losers. This can turn organizational life into a political war zone.

See Pfeiffer’s book, Managing with Power: Politics and influence in organizations (1992) to explore this metaphor further.

Organizations as organisms

This metaphor of organizational life sees the organization as a living, adaptive system. Gareth Morgan says, ‘The metaphor suggests that different environments favour different species of organisations based on different methods of organising … congruence with the environment is the key to success.’ For instance, in stable environments a more rigid bureaucratic organization would prosper. In more fluid, changing environments a looser, less structured type of organization would be more likely to survive.

This metaphor represents the organization as an ‘open system’. Organizations are seen as sets of interrelated sub-systems designed to balance the requirements of the environment with internal needs of groups and individuals. This approach implies that when designing organizations, we should always do this with the environment in mind. Emphasis is placed on scanning the environment, and developing a healthy adaptation to the outside world. Individual, group and organizational health and happiness are essential ingredients of this metaphor. The assumption is that if the social needs of individuals and groups in the organization are met, and the organization is well designed to meet the needs of the environment, there is more likelihood of healthy adaptive functioning of the whole system (socio-technical systems).

The key beliefs are:

- There is no ‘one best way’ to design or manage an organization.

- The flow of information between different parts of the systems and its environment is key to the organization’s success.

- It is important to maximize the fit between individual, team and organizational needs.

This leads to the following assumptions about organizational change:

- Changes are made only in response to changes in the external environment (rather than using an internal focus).

- Individuals and groups need to be psychologically aware of the need for change in order to adapt.

- The response to a change in the environment can be designed and worked towards.

- Participation and psychological support are necessary strategies for success.

What are the limitations of this metaphor? The idea of the organization as an adaptive system is flawed. The organization is not really just an adaptive unit, at the mercy of its environment. It can in reality shape the environment by collaborating with communities or with other organizations, or by initiating a new product or service that may change the environment in a significant way. In addition the idealized view of coherence and flow between functions and departments is often unrealistic. Sometimes different parts of the organization run independently, and do so for good reason. For example the research department might run in a very different way and entirely separately from the production department.

The other significant limitation of this view is noted by Morgan, and concerns the danger that this metaphor becomes an ideology. The resulting ideology says that individuals should be fully integrated with the organization. This means that work should be designed so that people can fulfil their personal needs through the organization. This can then become a philosophical bone of contention between ‘believers’ (often, but not always the HR Department) and ‘non-believers’ (often, but not always, the business directors). See Burns and Stalker’s book The Management of Innovation (1961) for the original thinking behind this metaphor.

Organizations as flux and transformation

Viewing organizations as flux and transformation takes us into areas such as complexity, chaos and paradox. This view of organizational life sees the organization as part of the environment, rather than as distinct from it. So instead of viewing the organization as a separate system that adapts to the environment, this metaphor allows us to look at organizations as simply part of the ebb and flow of the whole environment, with a capacity to self-organize, change and self-renew in line with a desire to have a certain identity.

This metaphor is the only one that begins to shed some light on how change happens in a turbulent world. This view implies that managers can nudge and shape progress, but cannot ever be in control of change. Gareth Morgan says, ‘In complex systems no one is ever in a position to control or design system operations in a comprehensive way. Form emerges. It cannot be imposed.’

The key beliefs are:

- Order naturally emerges out of chaos.

- Organizations have a natural capacity to self-renew.

- Organizational life is not governed by the rules of cause and effect.

- Key tensions are important in the emergence of new ways of doing things.

- The formal organizational structure (teams, hierarchies) only represents one of many dimensions of organizational life.

This leads to the following assumptions about organizational change:

- Change cannot be managed. It emerges.

- Managers are not outside the systems they manage. They are part of the whole environment.

- Tensions and conflicts are an important feature of emerging change.

- Managers act as enablers. They enable people to exchange views and focus on significant differences.

What are the limitations of this metaphor? This metaphor is disturbing for both managers and consultants. It does not lead to an action plan, or a process flow diagram or an agenda to follow. Other metaphors of change allow you to predict the process of change before it happens. With the flux and transformation metaphor, order emerges as you go along, and can only be made sense of after the event. This can lead to a sense of powerlessness that is disconcerting, but probably realistic!

See Shaw (2002) and Stacey (2001) for further reading on this metaphor.

STOP AND THINK!

|

3.1 |

Which view of organizational life is most prevalent in your organization? What are the implications of this for the organization’s ability to change? |

|

3.2 |

Which view are you most drawn to personally? What are the implications for you as a leader of change? |

|

3.3 |

Which views are being espoused here? (See A, B, C, D.) |

A―All staff memo from management team

The whole organization is encountering a range of difficult environmental issues, such as increased demand from our customers for faster delivery and higher quality, more legislation in key areas of our work, and rapidly developing competition in significant areas.

Please examine the attached information regarding the above (customer satisfaction data, benchmarking data vs competitors, details of new legislation) and start working in your teams on what this means for you, and how you might respond to these pressures.

The whole company will gather together in October of this year to begin to move forward with our ideas, and to strive for some alignment between different parts of the organization. We will present the management’s vision and decide on some concrete first steps.

B―E-mail from CEO

A number of people have spoken to me recently about their discomfort with the way we are tackling our biggest account. This seems to be an important issue for a lot of people. If you are interested in tackling this one, please come to an open discussion session in the Atrium on Tuesday between 10.00 and 12.00 where we will start to explore this area of discomfort. Let Sarah know if you intend to come.

C―E-mail from one manager to another

John seems to be in cahoots with Sarah on this issue. If we want their support for our plans we need to reshape our agenda to include their need for extra resource in the operations team. I will have a one to one with Sarah to check out her viewpoint. Perhaps you can speak to John.

Our next step should be to talk this through with the key players on the Executive Board and negotiate the necessary investment.

D―Announcement from MD

As you may know, consultants have been working with us to design our new objective setting process which is now complete. This will be rolled out starting 1 May 2003 starting with senior managers and cascading to team members.

The instructions for objective setting are very clear. Answers to frequently asked questions will appear on the company Web site next week.

This should all be working smoothly by end of May 2003.

MODELS OF AND APPROACHES TO ORGANIZATIONAL CHANGE

Now we have set the backdrop to organizational behaviour and our assumptions about how things really work, let us now examine ways of looking at organizational change as represented by the range of models and approaches developed by the key authors in this field. Table 3.2 links Gareth Morgan’s organizational metaphors with the models of and approaches to change discussed below.

|

Metaphor |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Model or approach |

Machine |

Political system |

Organism |

Flux and transformation |

|

Lewin, three-step model |

|

|

||

|

Bullock and Batten, planned change |

|

|||

|

Kotter, eight steps |

|

|

|

|

|

Beckhard and Harris, change formula |

|

|||

|

Nadler and Tushman, congruence model |

|

|

||

|

William Bridges, managing the transition |

|

|

|

|

|

Carnall, change management model |

|

|

||

|

Senge, systemic model |

|

|

|

|

|

Stacey and Shaw, complex responsive processes |

|

|

||

Lewin, three step model organism, machine

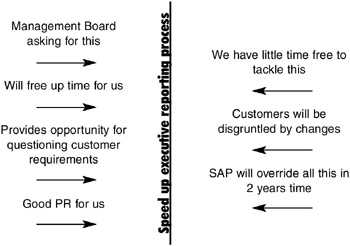

Kurt Lewin (1951) developed his ideas about organizational change from the perspective of the organism metaphor. His model of organizational change is well known and much quoted by managers today. Lewin is responsible for introducing force field analysis, which examines the driving and resisting forces in any change situation (see Figure 3.1). The underlying principle is that driving forces must outweigh resisting forces in any situation if change is to happen.

Figure 3.1: Lewin's force field analysis

Source: Lewin (1951)

Using the example illustrated in Figure 3.1, if the desire of a manager is to speed up the executive reporting process, then either the driving forces need to be augmented or the resisting forces decreased. Or even better, both of these must happen. This means for example ensuring that those responsible for making the changes to the executive reporting process are aware of how much time it will free up if they are successful, and what benefits this will have for them (augmenting driving force). It might also mean spending some time and effort managing customer expectations and supporting them in coping with the new process (reducing resisting force).

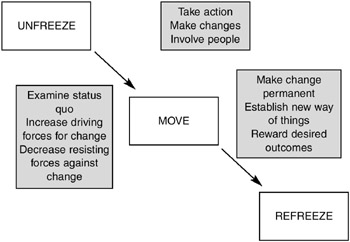

Lewin suggested a way of looking at the overall process of making changes. He proposed that organizational changes have three steps. The first step involves unfreezing the current state of affairs. This means defining the current state, surfacing the driving and resisting forces and picturing a desired end-state. The second is about moving to a new state through participation and involvement. The third focuses on refreezing and stabilizing the new state of affairs by setting policy, rewarding success and establishing new standards. See Figure 3.2 for the key steps in this process.

Figure 3.2: Lewin's three-step model

Source: Lewin (1951)

Lewin’s three-step model uses the organism metaphor of organizations, which includes the notion of homeostasis (see box). This is the tendency of an organization to maintain its equilibrium in response to disrupting changes. This means that any organization has a natural tendency to adjust itself back to its original steady state. Lewin argued that a new state of equilibrium has to be intentionally moved towards, and then strongly established, so that a change will ‘stick’.

Lewin’s model was designed to enable a process consultant to take a group of people through the unfreeze, move and refreeze stages. For example, if a team of people began to see the need to radically alter their recruitment process, the consultant would work with the team to surface the issues, move to the desired new state and reinforce that new state.

HOMEOSTASIS IN ACTION

In the 1990s many organizations embarked on TQM (total quality management) initiatives which involved focusing on customer satisfaction (both internally and externally) and process improvement in all areas of the organization. An Economic Intelligence Unit report indicated that two-thirds of these initiatives started well, but failed to keep the momentum going after 18 months. Focus groups were very active to start with, and suggestions from the front line came rolling in. After a while the focus groups stopped meeting and the suggestions dried up. Specific issues had been solved, but a new way or working had not emerged. Things reverted to the original state of affairs.

Our view

Lewin’s ideas provide a useful tool for those considering organizational change. The force field analysis is an excellent way of enabling for instance a management team to discuss and agree on the driving and resisting forces that currently exist in any change situation. When this analysis is used in combination with a collaborative definition of the current state versus the desired end state, a team can quickly move to defining the next steps in the change process. These next steps are usually combinations of:

- communicating the gap between the current state and the end state to the key players in the change process;

- working to minimize the resisting forces;

- working to maximize or make the most of driving forces;

- agreeing a change plan and a timeline for achieving the end state.

We have observed that this model is sometimes used by managers as a planning tool, rather than as an organizational development process. The unfreeze becomes a planning session. The move translates to implementation. The refreeze is a post-implementation review. This approach ignores the fundamental assumption of the organism metaphor that groups of people will change only if there is a felt need to do so. The change process can then turn into an ill-thought-out plan that does not tackle resistance and fails to harness the energy of the key players. This is rather like the process of blowing up a balloon and forgetting to tie a knot in the end!

Bullock and Batten, planned change machine

Bullock and Batten’s (1985) phases of planned change draw on the disciplines of project management. There are many similar ‘steps to changing your organization’ models to choose from. We have chosen Bullock and Batten’s:

- exploration;

- planning;

- action;

- integration.

Exploration involves verifying the need for change, and acquiring any specific resources (such as expertise) necessary for the change to go ahead. Planning is an activity involving key decision makers and technical experts. A diagnosis is completed and actions are sequenced in a change plan. The plan is signed off by management before moving into the action phase. Actions are completed according to plan, with feedback mechanisms which allow some replanning if things go off track. The final integration phase is started once the change plan has been fully actioned. Integration involves aligning the change with other areas in the organization, and formalizing them in some way via established mechanisms such as policies, rewards and company updates.

This particular approach implies the use of the machine metaphor of organizations. The model assumes that change can be defined and moved towards in a planned way. A project management approach simplifies the change process by isolating one part of the organizational machinery in order to make necessary changes, for example developing leadership skills in middle management, or reorganizing the sales team to give more engine power to key sales accounts.

Our view

This approach implies that the organizational change is a technical problem that can be solved with a definable technical solution. We have observed that this approach works well with isolated issues, but works less well when organizations are facing complex, unknowable change which may require those involved to discuss the current situation and possible futures at greater length before deciding on one approach.

For example we worked with one organization recently that, on receiving a directive from the CEO to ‘go global’, immediately set up four tightly defined projects to address the issue of becoming a global organization. These were labelled global communication, global values, global leadership and global balanced scorecard. While on the surface, this seems a sensible and structured approach, there was no upfront opportunity for people to build any awareness of current issues, or to talk and think more widely about what needed to change to support this directive. Predictably, the projects ran aground around the ‘action’ stage due to confusion about goals, and dwindling motivation within the project teams.

Kotter, eight steps machine, political, organism

Kotter’s (1995) ‘eight steps to transforming your organisation’ goes a little further than the basic machine metaphor. Kotter’s eight-step model derives from analysis of his consulting practice with 100 different organizations going through change. His research highlighted eight key lessons, and he converted these into a useful eight-step model. The model addresses some of the power issues around making change happen, highlights the importance of a ‘felt need’ for change in the organization, and emphasizes the need to communicate the vision and keep communication levels extremely high throughout the process (see box).

KOTTER’S EIGHT-STEP MODEL

- Establish a sense of urgency. Discussing today’s competitive realities, looking at potential future scenarios. Increasing the ‘felt-need’ for change.

- Form a powerful guiding coalition. Assembling a powerful group of people who can work well together.

- Create a vision. Building a vision to guide the change effort together with strategies for achieving this.

- Communicate the vision. Kotter emphasizes the need to communicate at least 10 times the amount you expect to have to communicate. The vision and accompanying strategies and new behaviours needs to be communicated in a variety of different ways.

The guiding coalition should be the first to role model new behaviours.

- Empower others to act on the vision. This step includes getting rid of obstacles to change such as unhelpful structures or systems. Allow people to experiment.

- Plan for and create short-term wins. Look for and advertise short-term visible improvements. Plan these in and reward people publicly for improvements.

- Consolidate improvements and produce still more change. Promote and reward those able to promote and work towards the vision. Energize the process of change with new projects, resources, change agents.

- Institutionalize new approaches. Ensure that everyone understands that the new behaviours lead to corporate success.

Source: Kotter (1995)

Our view

This eight-step model is one that appeals to many managers with whom we have worked. However, what it appears to encourage is an early burst of energy, followed by delegation and distance. The eight steps do not really emphasize the need for managers to follow through with as much energy on Step 7 and Step 8 as was necessary at the start. Kotter peaks early, using forceful concepts such as ‘urgency’ and ‘power’ and ‘vision’. Then after Step 5, words like ‘plan’, ‘consolidate’ and ‘institutionalize’ seem to imply a rather straightforward process that can be managed by others lower down the hierarchy. In our experience the change process is challenging and exciting and difficult all the way through.

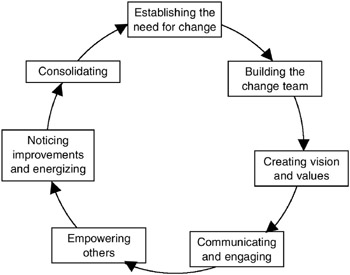

When we work as change consultants, we use our own model of organizational change (see Figure 3.3), which is based on our experiences of change, but has close parallels with Kotter’s eight steps. We prefer to model the change process as a continuous cycle rather than as a linear progression, and in our consultancy work we emphasize the importance of management attention through all phases of the process.

Figure 3.3: Cycle of change

Source: Cameron Change Consultancy Ltd

STOP AND THINK!

|

3.4 |

Reflect on an organizational change in which you were involved. How much planning was done at the start? What contribution did this make to the success or otherwise of the change? |

Beckhard and Harris, change formula organism

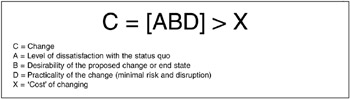

Beckhard and Harris (1987) developed their change formula from some original work by Gelicher. The change formula is a concise way of capturing the process of change, and identifying the factors that need to be strongly in place for change to happen.

Figure 3.4: Beckhard's formula

Beckhard and Harris say:

Factors A, B, and D must outweigh the perceived costs [X] for the change to occur. If any person or group whose commitment is needed is not sufficiently dissatisfied with the present state of affairs [A], eager to achieve the proposed end state [B] and convinced of the feasibility of the change [D], then the cost [X] of changing is too high, and that person will resist the change.

… resistance is normal and to be expected in any change effort. Resistance to change takes many forms; change managers need to analyze the type of resistance in order to work with it, reduce it, and secure the need for commitment from the resistant party.

The formula is sometimes written (A x B x D) > X. This adds something useful to the original formula. The multiplication implies that if any one factor is zero or near zero, the product will also be zero or near zero and the resistance to change will not be overcome. This means that if the vision is not clear, or dissatisfaction with the current state is not felt, or the plan is obscure, the likelihood of change is severely reduced. These factors (A, B, D) do not compensate for each other if one is low. All factors need to have weight.

This model comes from the organism metaphor of organizations, although it has been adopted by those working with a planned change approach to target management effort. Beckhard and Harris emphasized the need to design interventions that allow these three factors to surface in the organization.

Our view

This change formula is deceptively simple but extremely useful. It can be brought into play at any point in a change process to analyse how things are going. When the formula is shared with all parties involved in the change, it helps to illuminate what various parties need to do to make progress. This can highlight several of the following problem areas:

- Staff are not experiencing dissatisfaction with the status quo.

- The proposed end state has not been clearly communicated to key people.

- The proposed end state is not desirable to the change implementers.

- The tasks being given to those implementing the change are too complicated, or ill-defined.

We have noticed that depending on the metaphor in use, distinct differences in approach result from using this formula as a starting point. For instance, one public sector organization successfully used this formula to inform a highly consultative approach to organizational change. The vision was built and shared at a large-scale event involving hundreds of people. Dissatisfaction was captured using an employee survey that was fed back to everyone in the organization, and discussed at team meetings. Teams were asked to work locally on using the employee feedback and commonly created vision to define their own first steps.

In contrast, a FTSE 100 company based in the UK, used the formula as a basis for boosting its change management capability via a highly rated change management programme. Gaps in skills were defined and training workshops were run for the key managers in every significant project team around the company. Three areas of improvement were targeted:

- Vision: project managers were encouraged to build and communicate clearer, more compelling project goals.

- Dissatisfaction: this was translated into two elements, clear rationale and a felt sense of urgency. Project managers were encouraged to improve their ability to communicate a clear rationale for making changes. They were also advised to set clear deadlines and stick to them, and to visibly resource important initiatives, to increase the felt need for change.

- Practical first steps: project managers were advised to define their plans for change early in the process and to communicate these in a variety of ways, to improve the level of buy-in from implementers and stakeholders.

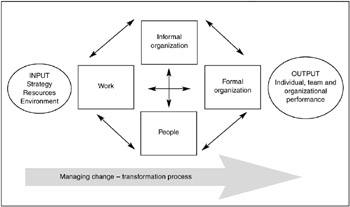

Nadler and Tushman, congruence model political, organism

Nadler and Tushman’s congruence model takes a different approach to looking at the factors influencing the success of the change process (Nadler and Tushman, 1997). This model aims to help us understand the dynamics of what happens in an organization when we try to change it.

This model is based on the belief that organizations can be viewed as sets of interacting sub-systems that scan and sense changes in the external environment. This model sits firmly in the open systems school of thought, which uses the organism metaphor to understand organizational behaviour. However, the political backdrop is not ignored; it appears as one of the sub-systems (informal organization – see below).

This model views the organization as a system that draws inputs from both internal and external sources (strategy, resources, environment) and transforms them into outputs (activities, behaviour and performance of the system at three levels: individual, group and total). The heart of the model is the opportunity it offers to analyse the transformation process in a way that does not give prescriptive answers, but instead stimulates thoughts on what needs to happen in a specific organizational context. David Nadler writes, ‘it’s important to view the congruence model as a tool for organizing your thinking … rather than as a rigid template to dissect, classify and compartmentalize what you observe. It’s a way of making sense out of a constantly changing kaleidoscope of information and impressions.’

The model draws on the sociotechnical view of organizations that looks at managerial, strategic, technical and social aspects of organizations, emphasizing the assumption that everything relies on everything else. This means that the different elements of the total system have to be aligned to achieve high performance as a whole system. Therefore the higher the congruence the higher the performance.

Figure 3.5: Nadler and Tushman's congruence model

Source: Nadler and Tushman (1997). Copyright Oxford University Press.

Use by permission of Oxford University Press, Inc.

In this model of the transformation process, the organization is composed of four components, or sub-systems, which are all dependent on each other. These are:

- The work. This is the actual day-to-day activities carried out by individuals. Process design, pressures on the individual and available rewards must all be considered under this element.

- The people. This is about the skills and characteristics of the people who work in an organization. What are their expectations, what are their backgrounds?

- The formal organization. This refers to the structure, systems and policies in place. How are things formally organized?

- The informal organization. This consists of all the unplanned, unwritten activities that emerge over time such as power, influence, values and norms.

This model proposes that effective management of change means attending to all four components, not just one or two components. Imagine tugging only one part of a child’s mobile. The whole mobile wobbles and oscillates for a bit, but eventually all the different components settle down to where they were originally. So it is with organizations. They easily revert to the original mode of operation unless you attend to all four components.

For example, if you change one component, such as the type of work done in an organization, you need to attend to the other three components too. The following questions pinpoint the other three components that may need to be aligned:

- How does the work now align with individual skills? (The people.)

- How does a change in the task line up with the way work is organized right now? (The formal organization.)

- What informal activities and areas of influence could be affected by this change in the task? (The informal organization.)

If alignment work is not done, then organizational ‘homeostasis’ (see above) will result in a return to the old equilibrium and change will fizzle out. The fizzling out results from forces that arise in the system as a direct result of lack of congruence. When a lack of congruence occurs, energy builds in the system in the form of resistance, control and power:

- Resistance comes from a fear of the unknown or a need for things to remain stable. A change imposed from the outside can be unsettling for individuals. It decreases their sense of independence. Resistance can be reduced through participation in future plans, and by increasing the anxiety about doing nothing (increasing the felt need for change).

- Control issues result from normal structures and processes being in flux. The change process may therefore need to be managed in a different way by for instance employing a transition manager.

- Power problems arise when there is a threat that power might be taken away from any currently powerful group or individual. This effect can be reduced through building a powerful coalition to take the change forward (see Kotter above).

Our view

The Nadler and Tushman model is useful because it provides a memorable checklist for those involved in making change happen. We have also noticed that this model is particularly good for pointing out in retrospect why changes did not work, which although psychologically satisfying is not always a productive exercise. It is important to note that this model is problem-focused rather than solution-focused, and lacks any reference to the powerful effects of a guiding vision, or to the need for setting and achieving goals.

We have found that the McKinsey seven ‘S’ model is a more rounded starting point for those facing organizational change. This model of organizations uses the same metaphor, representing the organization as a set of interconnected and interdependent sub-systems. Again, this model acts as a good checklist for those setting out to make organizational change, laying out which parts of the system need to adapt, and the knock-on effects of these changes in other parts of the system.

The seven ‘S’ categories are:

- Staff: important categories of people.

- Skills: distinctive capabilities of key people.

- Systems: routine processes.

- Style: management style and culture.

- Shared values: guiding principles.

- Strategy: organizational goals and plan, use of resources.

- Structure: the organization chart.

See Managing on the Edge by Richard Pascale (1990) for full definitions of the seven S framework.

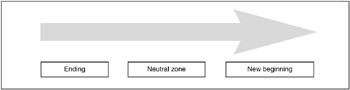

William Bridges, managing the transition machine, organism, flux and transformation

Bridges (1991) makes a clear distinction between planned change and transition. He labels transition as the more complex of the two, and focuses on enhancing our understanding of what goes on during transition and of how we can manage this process more effectively. In this way, he manages to separate the mechanistic functional changes from the natural human process of becoming emotionally aware of change and adapting to the new way of things.

Bridges says:

Transition is about letting go of the past and taking up new behaviours or ways of thinking. Planned change is about physically moving office, or installing new equipment, or restructuring. Transition lags behind planned change because it is more complex and harder to achieve. Change is situational and can be planned, whereas transition is psychological and less easy to manage.

Bridges’ ideas on transition lead to a deeper understanding of what is going on when an organizational change takes place. While focusing on the importance of understanding what is going on emotionally at each stage in the change process, Bridges also provides a list of useful activities to be attended to during each phase (see Chapter 4 on Leading change).

Transition consists of three phases: ending, neutral zone and new beginning.

Figure 3.6: Bridges: endings and beginnings

Ending

Before you can begin something new, you have to end what used to be. You need to identify who is losing what, expect a reaction and acknowledge the losses openly. Repeat information about what is changing – it will take time to sink in. Mark the endings.

Neutral zone

In the neutral zone, people feel disoriented. Motivation falls and anxiety rises. Consensus may break down as attitudes become polarized. It can also be quite a creative time. The manager’s job is to ensure that people recognize the neutral zone and treat it as part of the process. Temporary structures may be needed – possibly task forces and smaller teams. The manager needs to find a way of taking the pulse of the organization on a regular basis.

William Bridges suggested that we could learn from Moses and his time in the wilderness to really gain an understanding of how to manage people during the neutral zone.

MOSES AND THE NEUTRAL ZONE

- Magnify the plagues. Increase the felt need for change.

- Mark the ending. Make sure people are not hanging on to too much of the past.

- Deal with the murmuring. Don’t ignore people when they complain. It might be significant.

- Give people access to the decision makers. Two-way communication with the top is vital.

- Capitalize on the creative opportunity provided by the wilderness. The neutral zone provides a difference that allows for creative thinking and acting.

- Resist the urge to rush ahead. You can slow things down a little.

- Understand the neutral zone leadership is special. This is not a normal time. Normal rules do not apply.

Source: Bridges and Mitchell (2002)

New beginning

Beginnings should be nurtured carefully. They cannot be planned and predicted, but they can be encouraged, supported and reinforced. Bridges suggests that people need four key elements to help them make a new beginning:

- the purpose behind the change;

- a picture of how this new organization will look and feel;

- a step by step plan to get there;

- a part to play in the outcome.

The beginning is reached when people feel they can make the emotional commitment to doing something in a new way. Bridges makes the point that the neutral zone is longer and the endings are more protracted for those further down the management hierarchy. This can lead to impatience from managers who have emotionally stepped into a new beginning, while their people seem to lag behind, seemingly stuck in an ending (see box).

IMPATIENT FOR ENDINGS?

As part of the management team, I knew about the merger very early, so by the time we announced it to the rest of the company, we were ready to fly with the task ahead.

What was surprising, and annoying, was the slow speed with which everyone else caught up. My direct reports were asking detailed questions about their job specifications and exactly how it was all going to work when we had fully merged. Of course I couldn’t answer any of these questions. I was really irritated by this.

The CEO had to have a long, intensive heart to heart with the whole team explaining what was going on and how much we knew about the future state of the organization before we could really get moving.

Our view

This phased model is particularly useful when organizations are faced with inevitable changes such as closure of a site, redundancy, acquisition or merger. The endings and new beginnings are real tangible events in these situations, and the neutral zone important, though uncomfortable. It is more difficult to use the model for anticipatory change or home-grown change where the endings and beginning are more fluid, and therefore harder to discern.

We use this model when working with organizations embarking on mergers, acquisitions and significant partnership agreements. In particular, the model encourages everyone involved to get a sense of where they are in the process of transition. The image of the trapeze artist is often appreciated as it creates the feeling of leaping into the unknown, and trusting in a future that cannot be grasped fully. This is a scary process.

The other important message which Bridges communicates well is that those close to the changes (managers and team leaders) may experience a difficulty when they have reached a new beginning and their people are still working on an ending. This is one of the great frustrations of this type of change process, and we counsel managers to:

- recognize what is happening;

- assertively tell staff what will happen while acknowledging their feelings;

- be prepared to answer questions about the future again and again and again;

- say you don’t know, if you don’t know;

- expect the neutral zone to last a while and give it a positive name such as ‘setting our sights’ or ‘moving in’ or ‘getting to know you’.

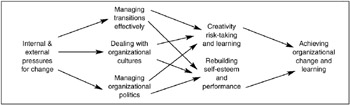

Carnall, change management model political, organism

Colin Carnall (1990) has produced a useful model that brings together a number of perspectives on change. He says that the effective management of change depends on the level of management skill in the following areas:

- managing transitions effectively;

- dealing with organizational cultures;

- managing organizational politics.

A manager who is skilled in managing transitions is able to help people to learn as they change, and create an atmosphere of openness and risk-taking.

A manager who deals with organizational cultures examines the current organizational culture and starts to develop what Carnall calls ‘a more adaptable culture’. This means for example developing better information flow, more openness, and greater local autonomy.

A manager who is able to manage organizational politics can understand and recognize different factions and different agendas. He or she develops skills in utilizing and recognizing various political tactics such as building coalitions, using outside experts and controlling the agenda.

Carnall (see Figure 3.7) makes the point that ‘only by synthesising the management of transition, dealing with organisational cultures and handling organisational politics constructively, can we create the environment in which creativity, risk-taking and the rebuilding of self-esteem and performance can be achieved’.

Figure 3.7: Carnall: managing transitions

Source: Carnall (1990). Printed with permission of Pearson Education Ltd.

Our view

Carnall’s model obviously focuses on the role of the manager during a change process, rather than illuminating the process of change. It provides a useful checklist for management attention, and has strong parallels with William Bridges’ ideas of endings, transitions and beginnings.

STOP AND THINK!

|

3.5 |

Compare the Nadler and Tushman congruence model with William Bridges’ ideas on managing transitions. How are these ideas the same? How are they different? |

Senge et al systemic model political, organism, flux and transformation

If you are interested in sustainable change, then the ideas and concepts in Senge et al (1999) will be of interest to you. This excellent book, The Dance of Change, seeks to help ‘those who care deeply about building new types of organisations’ to understand the challenges ahead.

Senge et al observe that many change initiatives fail to achieve hoped for results. They reflect on why this might be so, commenting, ‘To understand why sustaining significant change is so elusive, we need to think less like managers and more like biologists.’ Senge et al talk about the myriad of ‘balancing processes’ or forces of homeostasis which act to preserve the status quo in any organization.

HOMEOSTASIS IN ACTION

We wanted to move to a matrix structure for managing projects. There was significant investment of time and effort in this initiative as we anticipated payoff in terms of utilization of staff and ability to meet project deadlines. This approach would allow staff to be freed up when they were not fully utilized, so that they could work on a variety of projects.

Consultants worked with us to design the new structure. Job specs were rewritten. People understood their new roles. For a couple for months, it seemed to be working. But after four months, we discovered that the project managers were just carrying on working in the old way, as if they still owned the technical staff. They would even lie about utilization, just to stop other project managers from getting hold of their people.

I don’t think we have moved on very much at all.

Business Unit Manager, Research Projects Department

Senge et al say:

Most serious change initiatives eventually come up against issues embedded in our prevailing system of management. These include managers’ commitment to change as long as it doesn’t affect them; ‘undiscussable’ topics that feel risky to talk about; and the ingrained habit of attacking symptoms and ignoring deeper systemic causes of problems.

Their guidelines are:

- Start small.

- Grow steadily.

- Don’t plan the whole thing.

- Expect challenges – it will not go smoothly!

Senge et al use the principles of environmental systems to illustrate how organizations operate and to enhance our understanding of what forces are at play. Senge says in his book, The Fifth Discipline (Senge 1993):

Business and other human endeavours are also systems. They too are bound by invisible fabrics of interrelated actions, which often take years to fully play out their effects on each other. Since we are part of that lacework ourselves, it’s doubly hard to see the whole patterns of change. Instead we tend to focus on snapshots of isolated parts of the systems, and wonder why our deepest problems never seem to get solved.

The approach taken by Senge et al is noticeably different from much of the other work on change, which focuses on the early stages such as creating a vision, planning, finding energy to move forward and deciding on first steps. They look at the longer-term issues of sustaining and renewing organizational change. They examine the challenges of first initiating, second sustaining and third redesigning and rethinking change. The book does not give formulaic solutions, or ‘how to’ approaches, but rather gives ideas and suggestions for dealing with the balancing forces of equilibrium in organizational systems (resistance).

What are the balancing forces that those involved in change need to look out for? Senge et al say that the key challenges of initiating change are the balancing forces that arise when any group of people starts to do things differently:

- ‘We don’t have time for this stuff!’ People working on change initiatives will need extra time outside of the day to day to devote to change efforts, otherwise there will be push back.

- ‘We have no help!’ There will be new skills and mindsets to develop. People will need coaching and support to develop new capabilities.

- ‘This stuff isn’t relevant!’ Unless people are convinced of the need for effort to be invested, it will not happen.

- ‘They’re not walking the talk!’ People look for reinforcement of the new values or new behaviours from management. If this is not in place, there will be resistance to progress.

They go on to say that the challenges of sustaining change come to the fore when the pilot group (those who start the change) becomes successful and the change begins to touch the rest of the organization:

- ‘This stuff is _____!’ This challenge concerns the discomfort felt by individuals when they feel exposed or fearful about changes. This may be expressed in a number of different ways such as ,‘This stuff is taking our eye off the ball’, or ‘This stuff is more trouble that it’s worth.’

- ‘This stuff isn’t working!’ People outside the pilot group, and some of those within the pilot group, may be impatient for positive results. Traditional ways of measuring success do not always apply, and may end up giving a skewed view of progress.

- ‘We have the right way!’/’They don’t understand us!’ The pilot group members become evangelists for the change, setting up a reaction from the ‘outsiders’.

The challenges of redesigning and rethinking change appear when the change achieves some visible measure of success and starts to impact on ingrained organizational habits:

- ‘Who’s in charge of this stuff?’ This challenge is about the conflicts that can arise between successful pilot groups, who start to want to do more, and those who see themselves as the governing body of the organization.

- ‘We keep reinventing the wheel!’ The challenge of spreading knowledge of new ideas and processes around the organization is a tough one. People who are distant from the changes may not receive good quality information about what is going on.

- ‘Where are we going and what are we here for?’ Senge says, ‘engaging people around deep questions of purpose and strategy is fraught with challenges because it opens the door to a traditionally closed inner sanctum of top management’.

Our view

We like the ideas of Senge et al very much. They are thought-provoking and highly perceptive. If we can persuade clients to read the book, we will. However, in the current climate of time pressure and the need for fast results, these ideas are often a bitter pill for managers struggling to make change happen despite massive odds.

Whenever possible we encourage clients to be realistic in their quest for change, and to notice and protect areas where examples of the right sort of behaviours already exist. The messages we carry with us resulting from Senge et al’s thoughts are:

- Consider running a pilot for any large-scale organizational change.

- Keep your change process goals realistic, especially when it comes to timescales and securing resources.

- Understand your role in staying close to change efforts beyond the kick-off.

- Recognize and reward activities that are already going the right way.

- Be as open as you can about the purpose and mission of your enterprise.

There are no standard ‘one size fits all’ answers in the book, but plenty of thought-provoking ideas and suggestions, and a thoroughly inspirational reframing of traditional ways of looking at change. However, those interested in rapid large-scale organizational change are unlikely to find any reassurance or support in Senge et al’s book. The advice is, start small.

STOP AND THINK!

|

3.6 |

Reflect on an organizational change in which you were involved that failed to achieve hoped-for results. What were the balancing forces that acted against the change? Use Senge et al’s ideas to prompt your thinking. |

Stacey and Shaw, complex responsive processes political, flux and transformation

There is yet another school of thought represented by people such as Ralph Stacey (2001) and Patricia Shaw (2002). These writers use the metaphor of flux and transformation to view organizations. The implications of this mode of thinking for those interested in managing and enabling change are significant:

- Change, or a new order of things, will emerge naturally from clean communication, conflict and tension (not too much).

- As a manager, you are not outside of the system, controlling it, or planning to alter it, you are part of the whole environment.

In Patricia Shaw’s book Changing Conversations in Organizations, rather than address the traditional questions of ‘How do we manage change?’ she addresses the question, ‘How do we participate in the ways things change over time?’ This writing deals bravely with the paradox that ‘our interaction, no matter how considered or passionate, is always evolving in ways that we cannot control or predict in the longer term, no matter how sophisticated our planning tools’.

Our view

This is disturbing stuff, and a paradox that sets up some anxiety in managers and consultants who are disquieted by the suggestion that our intellectual strivings to collectively diagnose problems and design futures may be missing the point. Shaw says, ‘I want to help us appreciate ourselves as fellow improvisers in ensemble work, constantly constructing the future and our part in it’. Stacey says of traditional views of organizations as systems, ‘This is not to say that systems thinking has no use at all. It clearly does if one is trying to understand, and even more, trying to design interactions of a repetitive kind to achieve kinds of performance that are known in advance’.

Ralph Stacey and Patricia Shaw have both written about complexity and change. Managers, and particularly consultants, often find this difficult reading because on first viewing it appears to take away the rational powers we have traditionally endowed upon our managers, change agents and consultants. Patricia Shaw says of the traditional view of the process consultant:

I would say that [the] ideal of the reflective practitioner [who can surface subconscious needs so that groups of people can consciously create a directed form of change] is the one that mostly continues to grip our imaginations and shape our aspirations to be effective and competent individual practitioners engaged in lifelong learning. Instead, I have been asking what happens when spontaneity, unpredictability and our capacity to be surprised by ourselves are not explained away but kept at the very heart [of our work].

In contrast, those working in hugely complex environments such as the health sector or government have told us that they find the ideas in this area to be a tremendous relief. The notion that change cannot be managed reflects their own experiences of trying to manage change; the overwhelming feeling they have of constantly trying to push heavy weights uphill.

But how can managers and consultants use these ideas in real situations? We have distilled some groundrules for those working with complex change processes, although the literature we have researched studiously avoids any type of prescription for action.

In complex change, the leader’s role is to:

- Decide what business the organization is in, and stretch people’s thinking on how to get there.

- Ensure that there is a high level of connectivity between different parts of the organization, encouraging feedback, optimizing information flow, enabling learning.

- Focus people’s attention on important differences: between current and desired performance, between style of working, between past and present results.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

- It is useful to understand our own assumptions about managing change, in order to challenge them and examine the possibilities offered by different assumptions. It is useful to compare our own assumptions with the assumptions of others with whom we work. This increased understanding can often reduce frustration.

- Gareth’s Morgan’s work on organizational metaphors provides a useful way of looking at the range of assumptions that exist about how organizations work.

- The four most commonly used organizational metaphors are:

- the machine metaphor;

- the political metaphor;

- the organism metaphor;

- the flux and transformation metaphor.

- The machine metaphor is deeply ingrained in our ideas about how organizations run, so tends to inform many of the well-known approaches to organizational change, particularly project management, and planning oriented approaches.

- Models of organizations as open, interconnected, interdependent sub-systems sit within the organism metaphor. This model is very prevalent in the human resource world, as it underpins much of the thinking that drove the creation of the HR function in organizations. The organism metaphor views change as a process of adapting to changes in the environment. The focus is on designing interventions to decrease resistance to change, and increase the forces for change.

- The political map of organizational life is recognized by many of the key writers on organizational change as highly significant.

- The metaphor of flux and transformation appears to model the true complexity of how change really happens. If we use this lens to view organizational life it does not lead to neat formulae, or concise how-to approaches. There is less certainty to inform our actions. This can be on the one hand a great relief, and on the other hand quite frustrating.

- There are many approaches to managing and understanding change to choose from, none of which appears to tell the whole story, most of which are convincing up to a point. See Table 3.3 for a summary of our conclusions for each model.

Table 3.3: Our conclusions about each model of change Model

Conclusions

Lewin, three-step model

Lewin’s ideas are valuable when analysing the change process at the start of an initiative. His force-field analysis and current state/end state discussions are extremely useful tools.

However, the model loses its worth when it is confused with the mechanistic approach, and the three steps become ‘plan, implement, review’.

Bullock and Batten, planned change

The planned change approach is good for tackling isolated, less complex issues. It is not good when used to over-simplify organizational changes, as it ignores resistance and overlooks interdependencies between business units or sub-systems.

Kotter, eight steps

Kotter’s eight steps are an excellent starting point for those interested in making large or small-scale organizational change. The model places most emphasis on getting the early steps right: building coalition and setting the vision rather than later steps of empowerment and consolidation.

Change is seen as linear rather than cyclical, which implies that a pre-designed aim can be reached rather than iterated towards.

Beckhard and Harris, change formula

The change formula is simple but highly effective. It can be used at any point in the change process to analyse what is going on. It is useful for sharing with the whole team to illuminate barriers to change.

Nadler and Tushman, congruence model

The congruence model provides a memorable checklist for the change process, although we think the seven S model gives a more rounded approach to the same problem of examining interdependent organizational sub-systems.

Both are also useful for doing a post-change analysis of what went wrong!

Both encourage a problem focus rather than enabling a vision-setting process.

William Bridges, managing the transition

Bridge’s model of endings, neutral zone and beginnings is good for tackling inevitable changes such as redundancy, merger or acquisition. It is less good for understanding change grown from within, where endings and beginnings are less distinct.

Carnall, change management model

Carnall’s model combines a number of key elements of organizational change together in a neat process. Useful checklist.

Senge, systemic model

Senge challenges the notion of top-down, large-scale organizational change. He provides a hefty dose of realism for those facing organizational change: start small, grow steadily, don’t plan the whole thing.

However, this advice is hard to follow in today’s climate of fast pace, quick results and maximum effectiveness.

Stacey and Shaw, complex responsive processes

The complex responsive process school of thought is new, exciting and challenging; however it is not for the faint-hearted.

There are no easy solutions (if any at all), the leader’s role is hard to distinguish and the literature on the subject tends to be almost completely non-prescriptive.

- To be an effective manager or consultant we need to be able flexibly to select appropriate models and approaches for particular situations. See the illustrations of different approaches in Part Two.

STOP AND THINK!

|

3.7 |

Which model of organizational change would help you to move forward with each of the following changes:

|

|

3.8 |

A fast food organization introduced a set of values recently which were well communicated and enthusiastically welcomed. The senior management team publicly endorsed the values and said, ‘This is where we want to be in 12 months’ time so that we are ready for industry consolidation. You will all be measured on achieving these values in your day to day work.’ The values were put together by a consultancy, which put a great deal of effort into interviewing a broad range of people in the organization. People at all levels like the look of the values, but the situation three months later is that activity and conversations around the values are diminishing. A lot of people are saying ‘We are doing this already.’ There is still some enthusiasm, but people are now getting scared that they will fall short of the values somehow, and are starting to resent them. What needs to happen now? |

|

3.9 |

If Stacey and Shaw have ‘got it right’ with their ideas about how change emerges naturally, does that make books such as this one redundant? Answers on a postcard! |

Part I - The Underpinning Theory

Part II - The Applications

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 96