Mergers and acquisitions

OVERVIEW

This chapter addresses the specific change scenario of tackling a merger or an acquisition. We pose the following questions:

- Why do organizations get involved in mergers and acquisitions? Are there different aims, and therefore different tactics involved in making this type of activity work?

- Merger and acquisition activity has been very high over the last 10 years, and at a global scale. We must have learnt something from all this activity. What are the conclusions?

- Can the theory of change in individuals, groups and organizations be used to increase the success rate of mergers and acquisitions, and if so, how can it be applied?

The chapter has the following four sections:

- the purpose of merger and acquisition activity;

- lessons from research into successful and unsuccessful mergers and acquisitions;

- applying the change theory: guidelines for leaders;

- conclusions.

THE PURPOSE OF MERGER AND ACQUISITION ACTIVITY

We begin with a short history of mergers and acquisitions. It is useful to track the changes in direction that merger and acquisition activity have gone through over the last 100 years to achieve a sense of perspective on the different strategies employed. Gaughan (2002) refers to five waves of merger and acquisition activity since 1897 (see box), claiming that we are currently in the fifth wave of this ever-evolving field. However activity has slowed recently, with reported figures showing a 26 per cent reduction in global merger and acquisition activity in 2002.

THE FIVE WAVES OF MERGER AND ACQUISITION ACTIVITY

First wave (1897–1904): horizontal combinations and consolidations of several industries, US dominated.

Second wave (1916–29): mainly horizontal deals, but also many vertical deals, US dominated.

Third wave (1965–69): the conglomerate era involving acquisition of companies in different industries.

Fourth wave: (1981–89): the era of the corporate raider, financed by junk bonds.

Fifth wave: (1992–?): larger mega mergers, more activity in Europe and Asia. More strategic mergers designed to compliment company strategy.

Source: adapted from Gaughan (2002)

It is important to classify types of merger and acquisition to gain an understanding of the different motivations behind the activity. Gaughan (2002) points out that there are three types of merger or acquisition deal: a horizontal deal involves merging with or acquiring a competitor, a vertical deal involves merging with or acquiring a company with whom the firm has a supplier or customer relationship, and a conglomerate deal involves merging with or acquiring a company that is neither a competitor, nor a buyer nor a seller.

So why do companies embark on a merger or acquisition? The reasons are listed below.

Growth

Most mergers and acquisitions are about growth. Merging or acquiring another company provides a quick way of growing, which avoids the pain and uncertainty of internally generated growth. However, it brings with it the risks and challenges of realizing the intended benefits of this activity. The attractions of immediate revenue growth must be weighed up against the downsides of asking management to run an even larger company.

Growth normally involves acquiring new customers (for example, Vodafone and Airtouch), but can be about getting access to facilities, brands, trademarks, technology or even employees.

Synergy

Synergy is a familiar word in the mergers and acquisitions world. If two companies are thought to have synergy, this refers to the potential ability of the two organizations to be more successful when merged than they were apart (the whole is greater than the sum of the parts). This usually translates into:

- Growth in revenues through a newly created or strengthened product or service (hard to achieve).

- Cost reductions in core operating processes through economies of scale (easier to achieve).

- Financial synergies such as lowering the cost of capital (cost of borrowing, flotation costs).

However, there may be other gains. Some acquisitions can be motivated by the belief that the acquiring company has better management skills, and can therefore manage the acquired company’s assets and employees more successfully in the long term and more profitably.

Mergers and acquisitions can also be about strengthening quite specific areas, such as boosting research capability, or strengthening the distribution network.

Diversification

Diversification is about growing business outside the company’s traditional industry. This type of merger or acquisition was very popular during the third wave in the 1960s (see box). Although General Electric (GE) has flourished by following a strategy that embraced both diversification and divestiture, many companies following this course have been far less successful.

Diversification may result from a company’s need to develop a portfolio through nervousness about the earning potential of its current markets, or through a desire to enter a more profitable line of business. The latter is a tough target, and economic theory suggests that a diversification strategy to gain entry into more profitable areas of business will not be successful in the long run (see Gaughan, 2002 for more explanation of this).

A classic recent example of this going wrong is Marconi, which tried to diversify by buying US telecoms businesses. Unfortunately, this was just before the whole telecoms market crashed, and Marconi suffered badly from this strategy.

Integration to achieve economic gains

Another motive for merger and acquisition activity is to achieve horizontal integration. A company may decide to merge with or acquire a competitor to gain market share and increase its marketing strength.

Vertical integration is also an attraction. A company may decide to merge with or acquire a customer or a supplier to achieve at least one of the following:

- a dependable source of supply;

- the ability to demand specialized supply;

- lower costs of supply;

- improved competitive position.

Pressure to do a deal, any deal

There is often tremendous pressure on the CEO to reinvest cash and grow reported earnings (Selden and Colvin, 2003). He or she may be being advised to make the deal quickly before a competitor does, so much so that the CEO’s definition of success becomes completion of the deal rather than the longer-term programme of achieving intended benefits. This is dangerous because those merging or acquiring when in this frame of mind can easily overestimate potential revenue increases or costs savings. In short, they can get carried away.

Feldmann and Spratt (1999) warn of the seductive nature of merger and acquisition activity. ‘Executives everywhere, but most particularly those in the world’s largest corporations and institutions, have a knack for falling prey to their own hype and promotion…. Implementation is simply a detail and shareholder value is just around the corner. This is quite simply delusional thinking.’

|

Reason for M&A activity |

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

Organizational implications |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Growth |

Immediate revenue growth pleases shareholders. Reduction in competition (if other party is competitor). Good way of overcoming barriers to entry to specific areas of business. |

More work for the top team. Hard to sustain the benefits once initial savings have been made. Cultural problems often hard to overcome, thus potential not realized. |

Top team required to make a step change in performance. New arrivals in top team. Probably some administrative efficiencies. Integration in some areas if beneficial to results. |

|

Synergy |

May offer significant, easy cost-reduction benefits. Attractive concept for employees (unless they have ‘heard it all before’). |

More subtle forms of synergy such as product or service gains may be difficult to realize without significant effort. Cultural issues may cause problems that are hard to overcome. |

Top teams need to work closely together on key areas of synergy. Other areas left intact. |

|

Diversification |

May offer the possibility for entering new, inaccessible markets. Allows company to expand its portfolio if uncertain about current business levels. |

Economic theory suggests that potential gains of entering more profitable profit streams may not be realized. May be hard for top team to agree strategy due to little understanding of each other’s business areas. |

Loosely coupled management teams, joint reporting, some administrative efficiencies, separate identities and logos |

|

Integration |

Buyer or supplier power automatically reduced if other party is buyer or supplier. More control of customer demands or supply chain respectively. Reduction in competition (if other party is competitor). Increase in market share/marketing strength. |

More work for the top team. In the case of horizontal integration (other party is a competitor), cultural problems often hard to overcome, thus potential not realized. |

Integrated top team, merged administrative systems, tightly coupled core processes, single corporate identity |

|

Deal doing |

Seductive and thrilling. Publicity surrounding the deal augments the CEO’s and the company’s profile. |

The excitement of the deal may cloud the CEO’s judgement. |

Anyone’s guess! |

LESSONS FROM RESEARCH INTO SUCCESSFUL AND UNSUCCESSFUL MERGERS AND ACQUISITIONS

The following quote from Selden and Colvin (2003) gives us a starting point:

70% to 80% of acquisitions fail, meaning they create no wealth for the share owners of the acquiring company. Most often, in fact, they destroy wealth.… Deal volume during the historic M&A wave of 1995 to 2000 totalled more than $12 trillion. By an extremely conservative estimate, these deals annihilated at least $1 trillion of share-owner wealth.

Selden and Colvin put the problems down to companies failing to look beyond the lure of profits. They urge CEOs to examine the balance sheet, and say that M&As should be seen as a way to create shareholder value through customers, and should start with an analysis of customer profitability.

However, this contrasting quote from Alex Mandl, CEO of Teligent since 1996, in a Harvard Business Review interview (Carey, 2000) provides a different view:

I would take issue with the idea that most mergers end up being failures. I know there are studies in the 1970s and 80’s that will tell you that. But when I look at many companies today – particularly new economy companies like Cisco and WorldCom – I have a hard time dismissing the strategic power of M&A. In the last three years, growth through acquisition has been a critical part of the success of many companies operating in the new economy.

Carey’s interview occurred before the collapse of Enron and WorldCom, so he did not know what we know now. The recent demise of both Enron and WorldCom due to major scandals over illegal accounting practices has considerably dampened enthusiasm for merger and acquisition activity worldwide. These events have raised big questions about companies that finance continuous acquisitions as a core business strategy. The use of what BusinessWeek describes as ‘new era’ accounting is making investors nervous, and causing companies to be very careful with their investments and their financial reporting.

The discussion about the overall success rate of merger and acquisition activity still continues. But what lessons can be learnt from previous experience of undertaking these types of organizational change?

CASE STUDY OF SUCCESS: ISPAT

Ispat is an international steel-making company which successfully pursues long-term acquisition strategies. It is one of the world’s largest steel companies and its growth has come almost entirely through a decade-long series of acquisitions.

Ispat’s acquisitions are strictly focused. It never goes outside its core business. It has a well-honed due diligence process which it uses to learn about the people who are running the target company and convince them that joining Ispat will give them an opportunity to grow.

The company works with the potential acquisition’s management to develop a five-year business plan that will not only provide an acceptable return on investment, but chime with Ispat’s overall strategy.

Ispat relies on a team of 12 to 14 professionals to manage its acquisitions. Based in London, the team’s members have solid operational backgrounds and have worked together since 1991.

We have taken several different sources, all of which propose a set of rules for mergers and acquisitions, and distilled these into five learning points:

- Communicate constantly.

- Get the structure right.

- Tackle the cultural issues.

- Keep customers on board.

- Use a clear overall process.

Communicate constantly

In the excitement of the deal, company bosses often forget that the merger or acquisition is more than a financial deal or a strategic opportunity. It is a human transaction between people too. Top managers need to do more than simply state the facts and figures; they need to employ all sorts of methods of communication to enhance relationships, establish trust, get people to think and innovate together and build commitment to a joint future. They also need to use all the avenues available to them such as:

- company presentations;

- formal question and answer sessions;

- newsletters;

- team briefings;

- noticeboards;

- newsletters;

- e-mail communication;

- confidential helplines;

- Web sites with questions and answer session;

- conference calls.

COMMUNICATE CONSTANTLY

The top team had been working on the acquisition plans for over four months. Once the announcement was eventually made to all employees I just wanted to get on with things. I had so much enthusiasm for the deal. There was just endless business potential.

The difficulties came when I realized that not everyone shared my enthusiasm. My direct reports and their direct reports constantly asked me detailed questions about job roles and terms and conditions. It was beginning to really frustrate me that they couldn’t see the big picture.

I found I had to talk about our visions for the future and our schedule for sorting out the structure at least five times a day, if not more. People needed to hear and see me say it, and needed me to keep on saying it. I learned to keep my cool when repeating myself for the fifth time that day.

MD of acquiring company

Devine (1999) of Roffey Park says that managers with merger and acquisition experience tend to agree that it is impossible to over-communicate during a merger. They advocate the use of specific opportunities for staff to discuss company communications. They also advise managers to encourage their people to read e-mails and attend communication meetings, watching out for those who might be inclined to stick their heads in the sand. Managers need to be prepared as regards formal communications:

- Develop your answers to tricky questions before you meet up with the team.

- Expect some negative reactions and decide how to handle these.

- Be prepared to be open about the extent of your own knowledge.

Carey (2000) says it is necessary to have constant communication to counteract rumours. He advises, ‘When a company is acquired, people become extremely sensitive to every announcement. Managers need to constantly communicate to avoid the seizure that may come from over-reaction to badly delivered news.’

In company communications, it is very important to be clear on timescales, particularly when it comes to defining the new structure. People want to know how this merger or acquisition will affect them, and when. Carey (2000) says, ‘Everyone will be focused on the question “what happens to me?” They will not hear presentations about vision or strategic plans. They need the basic question regarding their own fate to be answered. If this cannot be done, then the management team should at least publish a plan for when it will be done.’

PRODUCTIVITY LEVELS DURING TIMES OF CHANGE

A very interesting statistic I once read says that people are normally productive for about 5–7 hours in an eight-hour business day. But any time a change of control takes place, their productivity falls to less than an hour.

Dennis Kozlowski, CEO Tyco International, quoted in Carey (2000)

Get the structure right

THE IMPORTANCE OF DECISIONS ABOUT STRUCTURE

At the time we thought it best to keep everyone happy and productive. Both the merged companies had good production managers, so we decided to ask them to work alongside each other, to share skills and learn a bit about the other person’s way of working.

We thought this was the best idea to keep production high, and to promote harmony and learning. However, in the end it turned out to be highly unproductive. It was a huge strain for the two individuals involved in both cases. They thought they were being set up to compete, despite protestations that this was not so. Both began to show signs of stress.

This structural decision (or rather indecision) also slowed the integration process down as people wanted to stay loyal to their original manager. They studiously avoided reporting at all to the new manager from the other company. Joint projects ended in stalemate and integration of working standards was almost impossible to achieve.

HR Director, involved in designing structure for merger

Structure is always a thorny issue for merging or acquiring companies. How do you create a structure that keeps the best of what is already there, while providing opportunities for the team to achieve the stretching targets that you aspire to?

Carey makes the point that it is essential to match the new company structure to the logic of the acquisition. If for example the intention was to fully integrate two sales teams to provide cost savings in administration and improve sales capability, then the structure should reflect this. It is tempting for senior managers to avoid conflict by appointing joint managers. Although this may work for the managers, it does not usually work for the teams. Integration becomes hard work as individuals prefer to keep reporting lines as they were.

Structure work should start early. Carey advises managers to begin working on the new structure before the deal is closed. Some companies use an integration team to work on this sort of planning. These people are in the ideal position to ask the CEO, ‘What was the intended gain of this acquisition?’ and ‘How will this structure support our goals?’

It is important that promotion opportunities provided by merger or acquisition activity are seen as golden opportunities for communicating the goals and values of the new company. Feldmann and Spratt (1999) warn against ‘putting turtles on fence posts’. They emphasize the importance of providing good role models, and encourage senior managers to promote only those who provide good examples of how they want things to be. They say ‘do not compromise on selection by indulging in a quota system (two of theirs and two of ours)’. And do not be tempted to fudge roles so that both people think they have got the best deal. This will only result in arguments and friction further down the line.

Tackle the cultural issues

Issues of cultural incompatibility have often been cited as problem areas when implementing a merger or acquisition. Merging a US and a European company can be complicated because management styles are very different. For instance US companies are known to be more aggressive with cost cutting, while European companies may take a longer view. Reward strategy and degree of centralization are also areas of difference. Jan Leschly, CEO of SmithKline Beecham, says in ‘Lessons for master acquirers’ (in Carey, 2000), ‘The British and American philosophies are so far apart on those subjects they’re almost impossible to reconcile.’

David Komansky, CEO of Merrill Lynch, made over 18 acquisitions between 1996 and 2001. In the same HBR article (Carey, 2000), he says:

It’s totally futile to impose a U.S.-centric culture on a global organization. We think of our business as a broad road within the bounds of our strategy and our principles of doing business. We don’t expect them to march down the white line, and, frankly, we don’t care too much if they are on the left-hand side of the road or the right-hand side of the road. You need to adapt to local ways of doing things.

The amount of cultural integration required depends on the reason for the merger or acquisition. If core processes are to be combined for economies of scale, then integration is important and needs to be given management time and attention. However, if the company acquires a portfolio of diverse businesses it is possible that culture integration will only be necessary at the senior management level.

The best way to integrate cultures is to get people working together on solving business problems and achieving results that could not have been achieved before the merger or acquisition. In ‘Making the deal real’ (Ashkenas, Demonaco and Francis, 1998), the authors have distilled their acquisition experiences at GE into four steps intended to bridge cultural gaps:

- Welcome and meet early with the new acquisition management team. Create a 100-day plan with their help.

- Communicate and keep the process going. Pay attention to audience, timing, mode and message. This does not just mean bulletins, but videos, memos, town meetings and visits from management.

- Address cultural issues head-on by running a focused, facilitated ‘cultural workout’ workshop with the new acquisition management team. This is grounded on analysis of cultural issues and focused on costs, brands, customers and technology.

- Cascade the integration process through, giving others access to a cultural workout.

Roffey Park research (Devine, 1999) confirms the need to tackle cultural issues. This research shows that culture clashes are the main source of merger failure and can cost as much as 25–30 per cent in lost performance. They identify some of the signs of a culture clash:

- People talk in terms of ‘them and us’.

- People glorify the past, talking of the ‘good old days’.

- Newcomers are vilified.

- There is obvious conflict – arguments, refusal to share information, forming coalitions.

- One party in the merger is portrayed as ‘stronger’ and the other as ‘weaker’.

Therefore an examination of existing cultures is normally useful if there is even a small possibility that cultural issues will get in the way of the merger or acquisition being successful. This is a good exercise to carry out in workshop format with the teams themselves at all levels. The best time to look at cultural issues is when teams are forming right at the start of the integration. It breaks the ice for people and allows them to find out a bit about each other’s history and company culture.

TACKLING THE CULTURAL ISSUES

The managers from company A described their culture as:

- fairly formal;

- courteous and caring;

- high standards;

- lots of team work;

- clear roles.

Company B added:

- precise;

- good reputation.

The managers from company B described their culture as:

- highly informal;

- a bit disorganized;

- relationships are important;

- customer focused;

- fast and fun.

Company A added:

- flexible roles;

- lack of hierarchy.

New culture – what did they need:

- role clarity;

- adaptability;

- high standards;

- customer focus;

- responsiveness;

- enjoyment;

- team work.

What might be the difficult areas:

- Balancing clarity of roles with adaptability – culture clash?

- Achieving high standards without getting too formal.

- Being responsive while keeping to high standards.

- Working as one team, rather than two teams.

Action plan:

- Define flexible roles for all management team. Must be half page long.

- Highlight areas where standards need to be reviewed.

- Audit customer responsiveness and set targets.

- Tackle each of the above by creating small task force with members from both companies.

Output from a management team meeting focusing on building a new culture.

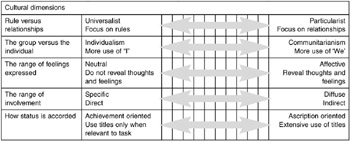

Cultural differences can be looked at using a simple cultural model such as the one offered in Riding the Waves of Culture: Understanding cultural diversity in business by Fons Trompenaars and Charles Hampden-Turner (1997). See Figure 6.1 for our representation of the various scales. People from each merger partner mark themselves on these scales and openly compare scores. In the workshop it is useful to ask the team to predict what kind of difficulties they might have as they start to work together, and to make an action plan to address these. We have run several such workshops, and in these we strongly encourage people to try to work together to define the new culture. This can be challenging work, especially if the acquisition or merger is perceived as hostile, but necessary work if any sort of integration is desired.

Figure 6.1: Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner's cultural dimensions

Source: Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner (1997).

Roffey Park’s advice appears below:

- Identify the key tactics used by team members to adhere to their own cultures.

- Identify cultural ‘hot-spots’, highly obvious differences in working practices that generate tension and conflict.

- Using a cultural model, get team members to explore the traits of their cultures, ask them what was good or bad about their former cultures.

- Get your people to identify cultural values of meanings that are important to them and that they wish to preserve.

- Challenge team members to identify a cluster of values that everyone can commit to and use as a foundation for working together.

Keep customers on board

Customers feel the effects first.… They don’t care about your internal problems, and they most certainly aren’t going to pay you to fix them.

(Feldmann and Spratt, 1999)

‘It’s very easy to be so focused on the deal that customers are forgotten. Early plans for who will control customer relationships after the merger or acquisition are essential,’ says Carey (2000). Devine (1999) adds weight to this by commenting:

Mergers are often highly charged and unpredictable experiences. It is all too easy to take your eye off the ball and to forget the very reason for your existence. Ensure that your team concentrates on work deliverables so that everyone remembers that there is a world outside and that it is still as competitive and pressurized as ever. Help everyone to realize that your competitors will be on the lookout for opportunities to exploit any weaknesses arising from the merger. You might find that in the face of an external threat, cultural differences shrink in importance.

Some of our experiences as consultants contradict the idea that increased focus on the customer can help a team to forget cultural differences. The opposite effect can happen, where teams and individuals from the two original merging companies use customer focus to further accentuate cultural difficulties:

- Sales people fight over customers and territory.

- Managers blame each other rather than help each other when accounts are lost.

- People from company A apologize to customers for the ‘shortcomings’ of people from company B rather than back them up.

This lesson accentuates the need to tackle cultural issues early, as well as to define clear groundrules for working with customers as one team.

HOW TO KEEP CUSTOMERS ON BOARD

One of our first actions was to embark on a series of customer visits that involved a senior sales person from both the merging companies. This allowed us to learn how to work together, and fast! It reassured customers and allowed us to deliver a clear message:

- we were now one company;

- there would be a single point of contact going forward;

- the merger was amicable and well managed.

Sales Manager from merged retail company

AVOIDING THE SEVEN DEADLY SINS

Feldmann and Spratt (1999) identify seven deadly sins in implementing a merger or acquisition. Their book goes on to describe in detail how to ensure that you avoid these problems.

- Sin 1: Obsessive list making. Don’t make lists of everything that needs to be done – it is exhausting and demoralizing. Instead, use the 80:20 rule. Focus on the 20 per cent of tasks that add the most value.

- Sin 2: Content-free communications. Don’t send out communications that contain only hype and promotion. Employees, customers, suppliers and shareholders all have real questions, so answer them.

- Sin 3: Creating a planning circus. Use targeted task forces, rather than a hierarchy of slow-paced committees.

- Sin 4: Barnyard behaviour. Unless roles and relationships are clarified, feathers will fly in an attempt to establish pecking order. Simply labelling the hierarchy will not sort this one out.

- Sin 5: Preaching vision and values. If you want cultural change, you have to work at it. It will not happen through proclamation.

- Sin 6: Putting turtles on fence posts. Ensure that the role models you select for promotion provide good examples of how you want things to be. Do not compromise on selection by indulging in a quota system (two of theirs and two of ours).

- Sin 7: Rewarding the wrong behaviours. Sort out compensation and link it to the right behaviours.

Use a clear overall process

The pitfalls associated with planning and successfully executing a merger or acquisition imply that it is important to have an overarching process to work to. GE’s Pathfinder Model is summarized in Table 6.2. It acts as a useful checklist for those involved in acquisition work (more in Ashkenas, Demonaco and Francis, 1998). This model, derived through internal discussion and review, forms the basis for GE’s acquisitions programme.

|

Preacquisition |

• Assess cultural strengths and potential barriers to integration. • Appoint integration manager. • Rate key managers of core units. • Develop strategy for communicating intentions and progress. |

|

Foundation building |

• Induct new executives into acquiring company’s core processes. • Jointly work on short and long-term business plans with new executives. • Visibly involve senior people. • Allocate the right resources and appoint the right people. |

|

Rapid Integration |

• Speed up integration by running cultural workshops and doing intensive joint process mapping. • Conduct process audits. • Pay attention to and learn from feedback as you go along. • Exchange managers for short-term learning opportunities. |

|

Assimilation |

• Keep on learning and developing shared tools, language, processes. • Continue longer-term management exchanges. • Make use of training and development facilities to keep the learning going. • Audit the integration process |

|

Source: Ashkenas, Demonaco and Francis (1998) |

|

USE A CLEAR PHASED PROCESS

It’s easy to get sucked into mindless list generation. There is an extraordinary amount of stuff to be done when you merge with another company. The trouble is that list making is very tiring, and the lists have to be numbered and monitored which takes time and effort. We found that it was much simpler to develop a phased process than to list everything that needed to be done. We then created a timeline with obvious milestones such as ‘structure chart delivered’, or ‘terms and conditions harmonized’. This helps people to keep on track without creating a circus of action planning and reporting.

Organization development manager talking about the merger of two management consultancies

APPLYING THE CHANGE THEORY GUIDELINES FOR LEADERS

Which elements of the theory discussed in earlier chapters can be used to inform those leading merger and acquisition activity? We make links with ideas about individual, team and organizational change to help leaders to channel their activities throughout this turbulent process. In addition, we refer to the previously mentioned research into successful mergers and acquisitions by Roffey Park Institute (Devine, 1999) which offers some useful guidelines for organizational leaders.

Managing the individuals

Mergers and acquisitions bring uncertainty, and uncertainty in turn brings anxiety. The question on every person’s mind is, ‘What happens to me in this?’ Once this question is answered satisfactorily, each individual can then begin to address the important challenges ahead. Until that time, there will be anxiety. Some people will be more anxious than others depending on their personal style, personal history and proximity to the proposed changes. And if people do not like the look of the future, there will be a reaction.

The job of the leader in a merger or acquisition situation is firstly to ensure that the team know things will not be the same any more. Second, he or she needs to ensure people understand what will change, what will stay the same, and when all this will happen. Third, the leader needs to provide the right environment for people to try out new ways of doing things.

Schein (see Chapter 1) claims that healthy individual change happens when there is a good balance between anxiety about the future and anxiety about trying out new ways of working. The first anxiety must be greater than the second, but the first must not be too high, otherwise there will be paralysis or chaos.

In a merger or acquisition situation there is very little safety. People are anxious about their futures as well as uncertain about what new behaviours are required. This means the leader has to create psychological safety by:

- painting pictures of the future; visioning;

- acting as a strong role model of desired behaviours;

- being consistent about systems and structures.

But not by:

- avoiding the truth;

- saying that nothing will change;

- hiding from the team;

- putting off the delivery of bad news.

Chapter 1 addressed individual change by first introducing three schools of thought:

- behavioural;

- cognitive;

- psychodynamic.

The behavioural model is useful as a reminder that reward strategies form an important part of the merger and acquisition process and must be addressed reasonably early. The cognitive model is based on the premise that our thinking affects our behaviour. This means that goal setting and role modelling too are important.

However, the psychodynamic approach provides the most useful model to explain the process of individual change during the various stages of a merger or acquisition. In Table 6.3 we use the Kubler-Ross model from Chapter 1 to illustrate individual experiences of change and effective management interventions during this process of change.

|

Stage |

Employee experience |

Management action |

|---|---|---|

|

Merger or acquisition is announced |

Shock. Disbelief. Relief that rumours are confirmed. |

Give full and early communication of reasons behind, and aims of this merger or acquisition |

|

Specific plans are announced |

Denial – it’s not really happening. Mixture of excitement and anxiety. Anger and blame – ‘This is all about greed’, If we’d won the ABC contract we wouldn’t be in this position now.’ |

Discuss implications of the merger or acquisition with individuals and team. Give people a timescale for clarification of the new structure and when they will know what their role will be in the new company. Acknowledge people’s needs and concerns even though you cannot solve them all. Be patient with people’s concerns. Be clear about the future. Find out and get back to them about the details you do not know yet. Do not take their emotional outbursts personally. |

|

Changes start to happen – new bosses, new customers, new colleagues, redundancies |

Depression – finally letting go of two companies, and accepting the new company. Acceptance. |

Acknowledge the ending of an era. Hold a wake for the old company and keep one or two bits of memorabilia (photos, T-shirts). Delegate new responsibilities to your team. Encourage experimentation, especially with building new relationships. Give positive feedback when people take risks. Create new joint goals. Discuss and agree new groundrules for the new team. Coach in new skills and behaviours. |

|

New organization begins to take shape |

Trying new things out. Finding new meaning. Optimism. New energy. |

Encourage risk taking. Foster communication at all levels between the two parties. Create development opportunities, especially where people can learn from new colleagues. Discuss new values and ways of working. Reflect on experience, reviewing how much things have changed since the start. Celebrate successes as one group. |

Managing the team

Endings and beginnings are important features of mergers and acquisitions, and these are most usefully addressed at the team level. The ideas of William Bridges (Chapter 3) provide a useful template for management activity during ending, the neutral zone and the new beginnings that occur during a merger or acquisition.

Managing endings

The endings are about saying goodbye to the old way of things. This might be specific ways of working, a familiar building, team mates, a high level of autonomy or some well-loved traditions. In the current era of belt-tightening and cost-cutting, there might be quite a lot of losses for people, similar to the effects of a restructuring exercise. (See Chapter 1 for more tips on handling redundancies.) Here is some advice for how managers can manage the ending phase (or how to get them to let go):

- Acknowledge that the old company is ending, or the old ways of doing things are ending.

- Give people time to grieve for the loss of familiar people if redundancies are made. Publish news of their progress in newsletters.

- Do something to mark the ending: for example have a team drink together specifically to acknowledge the last day of trading as the old company.

- Be respectful about the past. It is tempting to denigrate the old management team or the old ways of working to make the new company look more attractive. This will not work. It will just create resentment.

Managing the transition from old to new

This phase of a merger or acquisition, often known as integration, can be chaotic if it is not well managed. The ‘barnyard behaviour’ mentioned above combined with high anxiety about the future can lead to good people leaving and stress levels reaching all-time highs. Conflicts that are not nipped in the bud at this stage can lead to huge and permanent rifts between the two companies involved.

Tuckman’s model of team development is useful to explain what goes on in a new merged management team, or a newly merged sales team. We have also added some suggestions for how to manage these phases. See Table 6.4.

|

Stage |

Team activity |

Advice for leaders |

|---|---|---|

|

Forming |

• Confusion • Uncertainty • Assessing situation • Testing ground rules • Feeling out others • Defining goals • Getting acquainted • Establishing rules |

Be very clear about roles and responsibilities in the new company. Talk about where people have come from in terms of the structure, process and culture in their previous situation. Compare notes. Define key customers for the team and begin to agree new groundrules for how the team will work together. |

|

Storming |

• Disagreement over priorities • Struggle for leadership • Tension • Hostility • Clique formation |

Make time for team to discuss important issues. Be patient. Be clear on direction and purpose of the team. Nip conflict between cultures and people in the bud by talking to those involved. |

|

Norming |

• Consensus • Leadership accepted • Trust established • Standards set • New stable roles • Cooperation |

Develop decision-making process. Maintain flexibility by reviewing goals and process. |

|

Performing |

• Successful performance • Flexible task roles • Openness • Helpfulness |

Delegate more. Stretch people. Encourage innovation. |

Timing for this stage is also important. The integration stage should neither be squeezed into an impossible two-week period, nor be treated as an open-ended process that continues unaided for years. The need to squeeze this phase into a two-week period comes from management denial of the very existence of integration issues. Conversely, the need to let things take their course over time comes from a belief that time will solve all the issues and they cannot be hurried. Therefore they are allowed to drag on and possibly get worse, and more entrenched.

Bridges offers advice about managing the integration phase which we have adapted to be directly useful for mergers and acquisitions:

- Explain that the integration phase will be hard work and will need (and get) attention.

- Set short-range goals and checkpoints.

- Encourage experimentation and risk taking.

- Encourage people to brainstorm with members of the new company to find answers to both old and new problems.

Managing beginnings

It is important to recognize when the timing is right to celebrate a new beginning. Managers need to be careful not to declare victory too soon. Here are some ideas for this phase:

- Be really clear about the purpose of the merger or acquisition, and keep coming back to this as your bedrock.

- Paint a vision of the future for you and your team, describing an attractive future for those listening. (ROCE or ROI just doesn’t do it for most people!)

- Act as a role model by integrating well at your own level, and being seen to be doing so.

- Do something specific to celebrate a new beginning.

Managing yourself

There are many challenges ahead for managers as they enter a merger or acquisition. Managers may be uncertain about their own position, while attempting to reassure others about theirs. They may even be considering their options outside the organization while encouraging others to wait and see how things turn out.

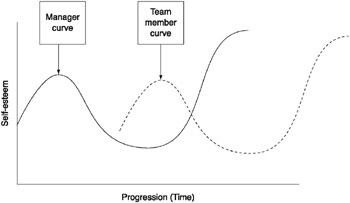

Other difficulties include the overwhelming needs of team members for clarity, reassurance and management time. Managers find themselves repeating information again and again, and become frustrated with their team’s inability to ‘move on’. A glance at the Kubler-Ross curves pictured in Figure 6.2 will reveal that this problem comes from managers and their teams being out of ‘sync’ in terms of their emotional reactions. While the manager is accepting the situation and trying out new ideas, the team is going through shock, denial, anger and blame. This is quite a stark mis-match!

Figure 6.2: Change curve comparisons

Devine (1999) offers a checklist for line managers:

- Get involved. Try to get in on the action and away from business as usual. Show you are capable of dealing with change.

- Get informed. Find out who is going up or down, especially among your sponsors or mentors. Have a ‘replacement’ boss you can turn to if your current one leaves.

- Get to know people. Network hard, get to know the people in the other company. Do not think of them as ‘the enemy’.

- Deal with your feelings. Openly recognize feelings of anxiety and frustration. Form a support network and discuss these feelings with colleagues.

- Actively manage your career. Think carefully before moving function/role at the time of a merger. You are remembered for your current job, whatever your past experience. Do not necessarily accept the first role that is offered to you. Decide what you would like to do, prepare your CV and work towards it – everything is up for grabs!

- Identify success criteria. Often performance criteria have changed or become unclear. Re-benchmark yourself by talking to people involved in the merger. Get informal feedback from subordinates, peers and bosses.

- Be positive. Be philosophical and objective about what is under your control. Do not beat yourself up – you can’t win ‘em all.

Handling difficult appointment and exit decisions

Mergers and acquisitions often involve a restructuring process, which in turn involves managers in making difficult appointment and exit decisions. These decisions need to be fair, transparent, justified, swift and carried out with attention to people’s dignity.

In one company that we know of, top management decided to reveal the newly merged company’s structure chart in a formal town hall meeting of all staff. Those who did not appear on the chart had to make their own conclusions. You can imagine the resentment and lack of trust that this foolish and undignified process generated.

Devine advises:

- New appointments need to be seen to be fair. Try to ensure that selection criteria are objective, transparent and widely understood.

- Stick to company policy and processes. Do not take short-cuts as they are likely to backfire on you.

- Do not dither. This will cause resentment.

- Treat employees at every level with dignity.

Managing the organization

It is important to select and agree a change process that matches the challenges posed by the specific merger and acquisition. If the most important challenge is to achieve cost-cutting goals, then project management techniques can be applied and the changes made swiftly. This may mean the use of a task force to make recommendations, and the agreement of a linear process for delivering the cost-cutting goals. However, if the most important challenges are integration issues or cultural issues, then the ideas of both Bridges and Senge are relevant. Attention must be paid to managing endings, transitions and beginnings for specific teams involved in significant processes. Other teams may remain untouched.

We have used the Kotter model, introduced in Chapter 3, to illustrate the steps from initial news of the deal to full integration. This model is useful because it combines a range of different assumptions about change, so tackles the widest range of possible challenges.

- Establish a sense of urgency. This is a tough balancing act for management. They must start to raise the issues that have led to the merger or acquisition without revealing the deal itself. For instance if the company is currently in a dwindling marketplace, then managers should highlight the need to do something about this, without necessarily revealing any intentions to buy or to merge. People will be suspicious and resentful of a deal that does not make any sense. ‘Why are we diversifying now? I thought the plan was to buy the competition!’

- Form a powerful guiding coalition. Managers of both companies need to begin working together as soon as they can. They need to spend time together and build a bit of trust. When the deal is announced, managers will then be able to work together at speed.

- Create a new vision. A top-level vision for the new company must be built by the new top management team. This vision will be used to guide the integration effort and to develop clear strategies for achieving this. The integration effort needs to be targeted in specific areas rather than be a blanket process, and clear timescales for implementation must be given.

The new structure needs to be put quickly into place, a level at a time, ensuring that customers are well managed throughout. The new sales and customer service structure is therefore also a priority. New values and ways of working should also be discussed and identified.

- Communicate the vision. Kotter emphasizes the need to communicate at least 10 times the amount you expect to have to communicate. In addition, all the research about mergers and acquisitions indicates that it is impossible to over-communicate. Managers need to be creative with their communication strategies, and remember to work hard at getting the two companies to build relationships at all levels.

The vision and accompanying strategies and new behaviours will need to be communicated in a variety of different ways: formal communications, role modelling, recruitment decisions and promotion decisions. The guiding coalition should be the first to role model new behaviours.

- Empower others to act on the vision. The management team now need to focus on removing obstacles to change such as structures that are not working, or cultural issues, or non-integrated systems. At this stage people are encouraged to experiment with new relationships and new ways of doing things.

- Plan for and create short-term wins. Managers should look for and advertise short-term visible improvements such as joint innovation projects, or the day-to-day achievements of joint teams. Anything that demonstrates progress towards the initial aims of the merger or acquisition is newsworthy. It is important to reward people publicly for merger-related improvements.

- Consolidate improvements and produce still more change. Top managers should make a point of promoting and rewarding those able to advocate and work towards the new vision. At this point it is important to energize the process of change with new joint projects, new resources, change agents.

- Institutionalize new approaches. It is vital to ensure that people see the links between the merger or acquisition and success. If they have had to work hard to make this initiative happen, they need to see that it has all been worthwhile.

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRUST WHEN GOING THROUGH A MERGER

When we were acquired by ITSS we were full of trepidation. Our previous owners had stripped us of costs and then looked around for a buyer. We felt a bit used. So we were in no mood to start building trust.

ITSS kept calling this deal a merger, but we were hugely cynical about that. They had bought us after all. This was a case of vertical integration where a supplier buys its customer to gain access to primary clients and grow the business. We thought they would start to take our jobs and move the company to their own headquarters, around four hours down the motorway!

The whole thing came to a head one morning when some consultants were running an integration workshop for the new management team. ITSS were getting frustrated with our hostility. We were getting angry about their constant questioning about finances and account management and project costs. Someone from our company was brave enough to share his emotions.

The MD of ITSS, who is actually a pretty decent guy, sat down amidst us all and spoke quite calmly for about 10 minutes. He said, ‘Look guys, I will do anything to make this company a success. Anything. But I need to know what I’m running here. I can’t take that responsibility without knowing all the facts. I really want us to make this thing a success. But I need your help.’

After that we trusted him a bit more. Then things got better and better. That was four years ago. Things have improved every year since then. He kept his word, and that was really important to everyone.

Project Leader, acquired company

SUMMARY

There are five main reasons for undertaking a merger or acquisition:

- growth;

- synergy;

- diversification;

- integration;

- deal doing.

Recent research indicates that five golden rules should be followed during mergers and acquisitions:

- Communicate constantly.

- Get the structure right.

- Tackle the cultural issues.

- Keep customers on board.

- Use a clear overall process.

Individuals can be managed through the process using the Kubler-Ross curve as a basis for understanding how people are likely to react to the changes. Teams can be managed through endings, transitions and new beginnings using the advice of Bridges. Tuckman’s forming, storming, norming, performing process also lends understanding to the sequences of activities that leaders of new joint teams need to take their teams through.

Managers need to manage themselves well through an integration process. Roffey Park’s advice is:

- Get involved.

- Get informed.

- Get to know people.

- Deal with your feelings.

- Actively manage your career.

- Identify success criteria.

- Be positive.

Difficult appointment and exit decisions also need to be well managed using these principles:

- Be fair.

- Stick to the procedures.

- Do not dither.

- Remember people’s dignity.

Kotter’s model can be used to plan a merger and acquisition process as it combines several different assumptions about the change process, so provides adequate flexibility for the range of different purposes of merger or acquisition activity.

Part I - The Underpinning Theory

Part II - The Applications

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 96