Market Orientation and Supply Chain Management in the Fashion Industry

Nobukaza J Azuma, John Fernie and Toshikazu Higashi

Introduction

The apparel industry has always been at the mercy of whims of styles and fickle customers who want the latest designs while they are still in fashion (Abernathy et al, 1999), along with uncontrollable parameters such as weather and economic conditions. The fashion market today is marked by ever-changing characteristics of consumers, competition and technologies. On the one hand, sophisticated consumers call for a relentless changeover of choices in products, brands, and even retail trading formats. A global spread of corporate activities in the textile and fashion industry, on the other hand, has accelerated the competition among fashion businesses at all levels. In addition to this, continuous improvement in the related technologies has created less room for a technology-driven differentiation and thus become a major barrier for a fashion firm to accomplish sustainable competitive advantage vis-à-vis its rivals (Tamura, 2003; Porter, 1985).

During the last few years, many apparel firms have forged their success by reshaping their supply chain and serving their customers in an increasingly timely manner. Quick Response (QR) within Supply Chain Management (SCM) has gained much attention as a key managerial philosophy (Fernie, 1994, 1998) to realize a firm’s market-oriented strategy. In this an organization seeks to understand and anticipate customers’ expressed and latent needs and develop superior solutions to these (Slater and Narver, 1999). The fashion industry is characterized by a high level of competitive intensity and market turbulence. It consists of notoriously labour-intensive multi-faceted processes with relative technological simplicity (Dickerson, 1995; Dicken, 1998). A successful implementation of a market orientation approach will, in theory, have a considerable impact upon improving a firm’s business performance (Jaworski and Kohli, 1993; Kohli and Jaworski, 1990) as well as augmenting its customer value.

Despite such a logical fit between the QR/SCM concept and the market orientation approach, it is indeed a challenge for a fashion firm to achieve a sustainable competitive advantage within the limited scope of innovation that is dictated by the fashion process (in which the trend is directed long before the start of each season at various stages, such as colour, fibre, yarn, fabric, print, silhouette, styling details, and trims – Jackson, 2001). This systematic process considerably increases the competitive intensity in the marketplace, together with a short-term competitive horizon (Tamura, 1996) that is peculiar to fashion. The condition for a fashion firm to differentiate itself from competition, therefore, is to create a subtle yet a communicable value to customers in a seemingly homogenized and yet fast-moving environment. The economy of speed (Minami, 2003) can no longer be the single driver of a firm’s competitive advantage, as time compression in the supply chain is increasingly becoming a de facto standard in the fashion industry.

This chapter investigates the factors that encompass fashion firms’ competitive strategies in such a dynamic yet institutionally constrained homogenized system. First, this chapter reviews the theories behind the concept of market orientation, including an extended view of marketing logistics (Christopher, 1997, 1998) and Supply Chain Management. It is followed by a discussion on the role of imitation and innovation as part of the organizational learning process and hence the competitive strategy in the fashion industry. The concluding part proposes a research agenda for future studies on the basis of the conceptual framework that is presented in this study.

Market Orientation Approach and Supply Chain Management A Focal Point

Competitive advantage is at the heart of a fashion firm’s performance in a volatile business environment (Lewis and Hawkesley, 1990), characterized by fragmented markets with dynamic consumers, rapid technological changes and growing non-price competition (Weerawardena, 2003; Tamura, 2003). Market orientation is an approach in which a business seeks to understand and anticipate customers’ expressed and latent needs, and develop superior solutions to these (Day, 1994; Kohli and Jaworski, 1990; Slater and Narver, 1995, 1999) in order to remain proactive as well as responsive to the changing nature of the marketplace.

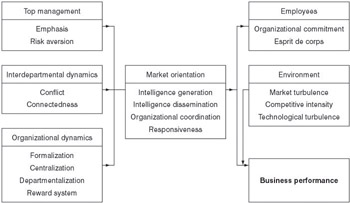

Market orientation (Figure 4.1) is the organization-wide generation of market intelligence pertaining to current and future customer needs, dissemination of the intelligence across departments, and organization- wide coordination (Tamura, 2003; Ogawa, 2000a, 2000b) and responsiveness to it (Kohli and Jaworski, 1990) in an efficient and effectual manner. Tamura (2003), building upon a series of conceptual frameworks of market-oriented strategy (Narver and Slater, 1990; Day, 1994; Kohli and Jaworski, 1990; Deshpande, Farley and Webster, 1993; Deshpande, 1999; Jaworski and Kohli, 1993), proposes an operationalization model of market orientation.

Figure 4.1: Antecedents and Consequences of Market Orientation

Much of the earlier literature (Narver and Slater, 1990; Day, 1994; Kohli and Jaworski, 1990; Deshpande, 1999; Jaworski and Kohli, 1993) is centred around the market orientation approach within the scope of a single firm’s internal organization mainly in the manufacturing sector. Kohli and Jaworski (1990) extrapolate the role of the supply-side and demand-side moderators and the environmental factors (such as market turbulence, competitive intensity and technological turbulence) (Jaworski and Kohli, 1993) as the external medium between a firm’s market orientation and its business performance. The former stands for the nature of the competition among suppliers and the technology employed within a firm’s value-adding behavioural system, and the latter represents the characteristics of demands in the industry, such as customer preferences and value consciousness.

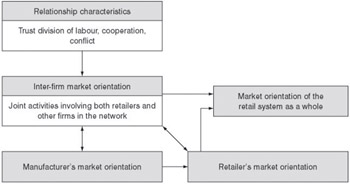

While such references to the roles of external factors imply the potential benefit of incorporating marketing logistics (Christopher, 1997, 1998; Christopher and Peck, 1998; Christopher and Juttner, 2000) into the market orientation approach, it is Elg (2003) who explicitly emphasizes the impacts of market orientation at an inter- as well as an intra-organizational level by defining it as a joint process by retailers, suppliers, and other supply chain members (Figure 4.2). This proposition is inspired by Siguaw, Simpson and Baker’s (1998, 1999) studies on the influence of a firm’s market orientation programme over other supply chain players in the network. Looking at the boundary between retailers and suppliers, Elg (2003) demonstrates the latent benefit that lies in this integrated market orientation approach.

Figure 4.2: A Framework for Analysing a Retailer’s Market Orientation

Dissemination and exchange of data about consumers among the members in a retail system (retailer’s supply chain) is likely to encourage each player in the network to better understand and anticipate customer needs and expectations. This also contributes to minimizing the ‘bullwhip effect’ by synchronizing the flow of information and inventories in the supply chain. Joint investment in sharing a common platform in delivering quick and effective market responses facilitates the supply chain players with opportunities to develop an interdependent (De Toni and Nassimbeni, 1995) long-term partnership. A trust that is created through a transaction-specific investment (Yahagi, 1994; Yahagi, Ogawa and Yoshida, 1993) is recognized as a critical factor to maintain an efficient and effectual inter-organizational virtual integration (Fiorito, Guinipero and Oh, 1999) in a long-term perspective.

In addition to these official settings in supply chain relationships, Elg (2003) singles out the salience of informal occasions where representatives of different members of a distribution network may meet and exchange information (Stern,El-Ansary and Coughalan, 1996) and insights. This viewpoint shares much in common with the notion of ‘shared space and atmosphere’ (Ba) that is introduced by Itami (1999) in the context of the product innovation process at a Japanese automotive company. It has often been applied to explain the agglomeration effects in the industrial districts in a number of studies in Japan (Yamashita, 1993, 1998, 2001; Nukata, 1998) and in Italy (Inagaki, 2003; Okamoto, 1994; Ogawa, 1998). The concept of ‘Ba’ sheds light on the ambiguous effect of supply chain members’ sharing of a common platform and encoding procedure towards a particular issue, upon directing the common goals and hence collaborative behaviours and a loop of organizational learning at both intra- and inter-organizational interfaces.

This last adds an important element or ‘missing piece’ to the classic view on Supply Chain Management, which places an emphasis on a rather IT investment-driven systematic approach (Forza and Vinelli, 1996, 1997, 2000; Hunter, 1990; Riddle et al, 1999) to achieve efficiency from raw materials to retail sales floors. The traditional supply chain approach focuses on an orderly shift from a transaction-based buyer–supplier relationship to a network-based (Tamura, 2001) partnership (Figure 4.3), which is often explained by a dyadic node of communications between the two parties (Christopher, 1997, 1998; Fernie, 1994, 1998; Azuma and Fernie, forthcoming). The role of ‘Ba’ is deemed to be a moderating factor in the supply chain in that it facilitates the involved parties with motivations to keep creating a unique value in a seemingly fixed and stabilized partnership environment, which otherwise can become a major inhibitor of continuous innovation. An intra- and inter-organizational learning loop in the supply chain not only deals with the ongoing and latent needs and expectations of the customers, but also serves as an implicit agent to monitor the competition’s moves and innovatively copy (Levitt, 1969, 1983; Takeishi, 2001) their operational excellence to gain advantage in the competitive league in the volatile world of fashion.

Figure 4.3: Traditional Buyer–Supplier Relationship (Left) and Partnership Buyer–Supplier Relationship (Right)

Figure 4.4 summarizes the relationship between a firm’s market- oriented strategy and the role of the supply chain in organically coordinating a series of actions in the external as well as internal processes of market orientation; first, recognition of the market environment; second, generation of intelligence on the customer ’s existing needs and latent/future expectations; third, intra and inter-organizational dissemination of the intelligence; and fourth, responses to satisfy the needs and feedback of the actions (Pelham, 1997; Tamura, 2001, 2003).

Figure 4.4: The Conceptual Model of the Market Orientation Approach in the Fashion Industry

The objectives of Quick Response and Supply Chain Management in the fashion industry are far simpler than trade-offs between the size of IT (SCM enablers) investment and the actual impact of SCM on improving the pipeline throughput and financial performance (Fiorito et al, 1999; Tamura, 2001). A supply chain, as Porter (1985) describes in the value system concept, is a network of independent firms’ value chains that are involved in the production and marketing of particular products and services. This network of value chains targets customer satisfaction, while the traditional value chain approach intends to increase a firm’s profit margin (McGee and Johnson, 1987). Supply chain, in this sense, is a fundamental behavioural architecture in which any market-oriented firm may find itself involved, and therefore it is not a system to be configured from scratch, but an existing framework that needs refinement and restructuring in accordance with the degrees of a firm’s market orientation. Particularly in the fashion industry where highly fragmented small and medium-sized enterprise (SME) contractors perform many of the supply chain phases, the organizational aspect of supply chain management should be given more credibility than the IT investment versus economies of scale justification.

To put it simply, the goals of supply chain management in the fashion industry are, therefore, in delivering the in-vogue style at the right time in the right place (Fernie, 1994), with increased variety and affordability (Giunipero et al, 2001; Lowson, 1998; Lowson, King and Hunter, 1999) and more room for customization (Pine, 1993), thus satisfying both the existing and potential needs of the customers (Slater and Narver, 1999). In other words QR/SCM, in theory, is a medium that induces an organization to create superior customer value, and hence achieve a competitive advantage in the volatile marketplace (Porter, 1985).

At an operational level, the concepts of QR and SCM require a firm and its supply chain partnerships to coordinate their internal and external activities (Chandra and Kumar, 2000) in order to translate their shared intelligence on customers’ needs and expectations into a proactive response to the market fluctuation and the future demands. They aim at accurately forecasting the market trends and flexibly synchronizing these with the entire process in the supply chain, based upon an efficient and effective sharing of key information, and the risks and benefits that are embedded in the long and complex pipeline (Christopher, 1997, 1998; Christopher and Juttner, 2000).

Thus it would be reasonable, at least at a theoretical level, to integrate the action flow in the market orientation approach into an extended concept of marketing logistics and Supply Chain Management (Christopher, 1997, 1998; Christopher and Peck, 1998; Christopher and Juttner, 2000), since it is consistent with the intra- and inter-firm coordination mechanism of the supply chain in delivering a flexible and rapid response to the current and foreseen needs of the customer.

Market Orientation Approach and Supply Chain Management The Reality

Despite such a strong potential for a market orientation being rooted in the SCM philosophy, it is hardly possible for a fashion firm to establish a sustainable competitive advantage solely through its market orientation and supply chain effectiveness. This is due partly to an institutional mechanism in which the fashion trend is set farther ahead of the beginning of each season by a variety of international bodies at various levels, such as colour directions, fibre, yarn, fabric, print and finish, silhouette, styling details, and trims (Jackson, 2001; Chimura, 2001). Even the designs presented on the international catwalks mostly find their origins in design movements, exotic costumes, styles on the street, and other sources that share a continuity from the past, although futuristic as well as contemporary components are always added on to the new collection.

This systematic fashion process of planned creation and obsolescence considerably limits the scope of innovation and thus increases the competitive intensity in the fashion industry towards the state of competitive myopia (Tamura, 1996). No one creation in the history of modern fashion is as epoch-making as the cornerstone innovations in other industries, such as James Watt’s and Edison’s or more recently the Internet, in terms of the impacts upon the lifestyle of people. Due to its relative simplicity in related technologies and uniformity in the usage of clothes, a breakthrough innovation (Schumpeter, 1934) is unlikely to take place in the fashion industry. While production technologies and consumer preferences in the fashion industry are in a constant change and sophistication, their degree of mutation does not reach the extent that it invalidates or ‘de-matures’ (Abernathy, Clark and Kantrow, 1983) the existing technological and design paradigm (Kuhn, 1970; Dosi, 1982; Takeishi, 2001).

Fashion is, indeed, a unique phenomenon. It consistently transforms and fluctuates, reflecting the mood of the society. The degree of metamorphosis, however, is within a nominal but a discernable extent in the mind of the consumer. The condition for a fashion firm to differentiate from competition, therefore, is to create a subtle yet appealing difference to the customers in an apparently homogenized environment, where the economy of speed (Minami, 2003) can no longer deliver a sustainable competitive advantage. Compression in the three dimensions of time in marketing the fashion style, serving the customers and reacting to market change (Christopher and Peck, 1998; Hines, 2001) within a supply chain has been becoming a de facto standard in the fashion industry.

If one assumes an entrepreneurial risk and explores ideas to achieve a higher level of intrinsic differentiation by increasing levels of product transformation, the ideal means would be by bringing the decoupling point at the material development stage back up the supply chain (Meijbroom, 1999). It nevertheless involves a significant risk to commit too much to backward speculation (Yahagi, 2001), because a firm is then required to trade off the variety of its fashion offers with the postponement benefits. The order lot size is far larger in the materials than in the finished apparel products, and lead times are lengthier in the upstream sector. To narrow down the variety in materials not only deprives a firm of its organizational agility (Tamura, 1996) to effectively respond to market fluctuation but also affects its financial performances, once the trend ceases to be up for the business. The Japanese women’s clothing sector, for example, calls for a considerable variety in designs and hence diversity in the choice of materials (Azuma and Fernie, forthcoming). Some of the functions delivered by textile converters, such as assortment in a smaller lot size, risk avoidance, finance, conveyance of market information, and introduction of cutting-edge materials (Tamura, 1975), are indispensable in order to execute market-oriented responses to the ever-changing fragmented needs of the consumer. Thus, there still remains a question regarding this trade-off issue in the fashion supply chain.

Besides, the relationships among the supply chain members in reality tend not to be motivated by common goals and objectives that are based upon an effective sharing of key information and an efficient flow of inventories in the entire supply chain. It is too often the case in the fashion industry that an extreme responsiveness of a firm’s fashion supply chain is achieved through an unequal distribution of power. The players who command the creative shrewdness and the marketing function in the midto-downstream parts of the pipeline effectually impose a flexible response in the labour-intensive processes on their SME subcontractors who are mostly dependent on their orders (Azuma, 2001; Azuma and Fernie, forthcoming). An effective sharing of ‘Ba’, in reality, is hard to realize in a power- game relationship (Fernie, 1998; Whiteoak, 1994). Therefore, collaborative creation of a unique value ‘from the source’ is normally hard to achieve for a fashion firm, coupled with the speculation/postponement issue (Bucklin, 1965; Alderson, 1957) mentioned above.

Thus, the competitive environment in the fashion industry is configured in a somewhat unique way, and this makes it difficult for a fashion firm to differentiate from competition simply via implementing a market-oriented supply chain approach. An integrated programme of market orientation and Supply Chain Management certainly provides a fashion firm and its supply chain partnerships with better visibility of its market orientation activities and helps them deliver a rapid and flexible response to the actual and latent needs in the marketplace. Nevertheless, it does not allow a firm to achieve a concrete differentiation and hence a sustainable competitive advantage. Being locked up itself in a partnership with a smaller number of suppliers, based on a transaction-specific investment, a firm would gradually decrease its capability in satisfying the market needs for variety and in executing effective organizational learning in both official and unofficial settings.

It is indeed paradoxical that an inter- and intra- organizational approach to anticipate and better respond to the changing needs of the customers results in homogenizing firms’ responses to the consumers within the restrained scope of innovation in the fashion industry. A rapid and flexible response is often just a prerequisite for a fashion firm to avoid being left out in the midst of harsh competition. Then, what are the real drivers of differentiation in the fashion market?

The Role of Imitation and Innovation in the Fashion Business

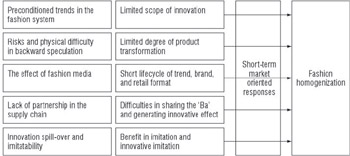

The fashion industry is an institutional system in which firms’ market- oriented commitment can very often result in an apparent homogenization in the fashion retail mix beyond the boundaries of companies as well as brand labels (Azuma and Fernie, forthcoming). In addition to the restraint on the scope of innovation and the degree of product transformation, due to the systematic mechanism of shaping trends and the difficulties in bringing the decoupling point (Meijboom, 1999) up the supply chain, there is a complex set of factors that prohibits a clear-cut fashion differentiation in the marketplace.

While an increasing number of fashion firms have gained much of their time-based competitive capability (Stalk and Hout, 1990; Maximov and Gottschilich, 1993) via a flexible and responsive supply chain, their responses to market change are predominantly short-term oriented. This is partially because there exists a power-game relationship within the inter-firm network in the pipeline (Fernie, 1998; Whiteoak, 1994; Azuma, 2001; Azuma and Fernie, forthcoming). It prevents the creative effect of sharing ‘Ba’ among the supply chain members from being realized, and reduces the degree of intrinsic differentiation from the materials stage. Stronger members in the supply chain are more prone to gleaning a short-term benefit than pursuing a long-term competitive edge. Their contracted suppliers, on the other hand, are historically highly dependent on their order placements and so have not developed their own innovative function. A truly collaborative market-oriented supply chain in a fast-moving environment is indeed hard to organize for a shared goal and objective.

The influence of fashion media is another factor that inhibits a fashion firm’s sustainable competitive advantage. These media, especially the fashion press, persistently feature the upcoming trend and styles, and simultaneously invalidate the trend in the ‘near past’. Thus, what is ‘in’ at present can possibly become an ‘out’, even overnight, through the power of the media. The positioning of a fashion firm in the marketplace is, by the same token, susceptible to ‘what the fashion press says’ in addition to ‘what the consumers expect’.

Finally, innovation spill-over (Porter, 1985; Takeishi, 2001) is a very conspicuous phenomenon in the fashion industry. Earlier studies have identified a set of inhibitors of imitation (Levin et al, 1998; Teece, 1986; Williams, 1992; Rumelt, 1984; White, 1982; Porter, 1996; Besanko, Dranove and Shanley, 2000):

- legal and regulatory protection;

- superior access to the materials, resources, and customers;

- the size of the market and the economies of scale;

- company-specific intangible capabilities;

- strategic fit.

In the fashion industry, however, most of these barriers are less effective to prevent imitators, due to the nature of the industry. First of all, tangible aspects of the fashion retail mix, such as products and retail formats, can easily be copied through observation and reverse engineering (Von Hippel, 1988), and it is almost impossible to ban the ‘me-toos’ and the innovative imitators (Levitt, 1969, 1983). In fact, many of the so-called innovative high street retailers, such as The Limited, Zara, and many of the Japanese players have developed their capability to adapt external fashion sources in their own style (Minami, 2003; Levitt, 1969, 1983; Burt, Dawson and Larke, 2003; Azuma, 2002; Fisher, Raman and McClelland, 1999) through their market-oriented supply chain approaches.

Even the know-how and expertise in the backyard of the retail mix is not secure from competitors’ intelligence activities (Tamura, 2003). Since firms share common suppliers, interior decorators, consulting firms, sales promotion companies, third-party logistics service providers, credit card operators and IT service providers, a fashion firm’s operational secrets are sometimes passed on from one party to another, thus decimating the operational competence of a company. Higher occurrences of jobhopping in the fashion industry too stimulate the leakage of such tacit knowledge from one company to another. This fluid movement of human resources in the entire industry encourages the formation of unofficial human contacts and thus, a tacit knowledge that works within the particular environment at a specific company is translated into a common knowledge among a much larger group of the players in the industry.

Figure 4.5 summarizes the nature of the competition and innovation in the fashion industry, and describes why the market-oriented approach in the fashion business tends to take on a short-term competitive horizon. Taking the institutional and operational characteristics of the fashion industry into consideration, firms’ short-termism in their market orientation would be logical, as there exist few opportunities to leverage from the fast-mover advantage and establish a sustainable competitive advantage (Levitt, 1969; Schnaars, 1994).

Figure 4.5: The Process of Fashion Homogenization

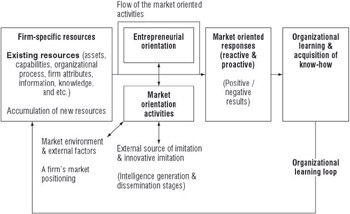

Fashion firms’ market-oriented supply chain behaviours are rather sustained by an organizational learning loop of their market operation. As Weerawardena (2003) explains, it is not solely the heterogeneous firm- specific resources (Rumelt, 1984; Montgomery and Wernerfelt, 1988;Barney, 1991), such as all assets, capabilities, organizational processes, firm attributes, information, and knowledge, that determine a firm’s source of competitive advantages. Resources do not exclusively determine what the firm can do and how well it can do it (Grant, 1991; Weerawardena, 2003). It is a firm’s capabilities to make better use of available resources (Penrose, 1955; Mahoney and Pandian, 1992; Weerawardena, 2003) that help it achieve real rents, although the corporate capability itself is counted as part of the resources.

In the context of the fashion industry, this capability-based approach fits well into the framework of firms’ market-oriented supply chain activities. Fashion firms are consistently faced with a situation in which their current competitive excellence is innovatively imitated or leapfrogged by their entrepreneurial competition at any point of time. While this is a natural phenomenon in the volatile world of fashion, such a competitive intensity, coupled with the institutional factors, requires fashion firms to continuously monitor each other as well as their customers’ needs and then create a subtle yet a unique ‘difference’ that better satisfies the customers’ expectations than do their rivals. This continuous loop of imitation, continuous subtle innovation, organizational learning and resultant accumulation of new resources, and a firm’s capability to utilize its internal and external resources, are deemed the determinants of a fashion firm’s competitive advantage in the short-term volatile competitive horizon.

This sequence of imitation and innovation among competitors is persistently taking place within the setting of their integrated market-oriented supply chain. The business that translates the unstated needs of the customer can create a subtle yet an effective difference in a seemingly homogenized market environment. In addition to this, the loop of the short-term market-oriented responses to the marketplace plays a crucial role in turning the wheel of innovation in the fashion industry, although the nature of the innovation is incremental due to the industry’s specificity. Figure 4.6 depicts the organizational learning loop within a fashion firm’s market-orientation approach.

Figure 4.6: Organizational Learning Model in a Fashion Firm’s Market Orientation

Conclusion and the Research Agenda For Future Studies

This chapter has explored the unique nature of competition in the fashion industry from the viewpoint of market orientation and Supply Chain Management. An integrated approach of these two concepts is found, in theory, to create a great potential for a fashion firm (and its supply chain members) to enhance business performances and hence achieve a sustainable competitive advantage by effectively translating latent as well as existing customer needs and expectations into market responses.

The limited scope of innovation in the fashion industry, however, hinders an intrinsic fashion differentiation from taking place, and so fashion firms tend to build their market-oriented activities upon a short- term competitive horizon. Thus, a firm’s capability to innovatively copy its competition in the process of the market-oriented supply chain is the determinant of its competitive advantage in the midst of ever-changing needs and expectations of the consumers in the marketplace. An implication is that a firm’s long-term success in such an environment is thus dependent on its capability in organizationally learning from the past, present, and future of its market-oriented activities in the restrained but yet volatile environment.

While this study has focused on a theoretical discussion and identified some of the key factors in the fashion industry that affect fashion firms’ market-oriented supply chain strategies, there exists a strong need to empirically analyse the nature of the competition, degree of homogenization of the fashion market, and key retail mix components for differentiation in a seemingly homogenized market place. Particularly for the degree of homogenization and key retail mix components, it will be worthwhile to compare and contrast firms’ perception of their own retail mix with consumers’ relative evaluation of different firms’ retail mix, since a fashion firm’s retail mix is a major consequence of its market-oriented supply chain activities. An intensive analysis of the gap between the two parties will reveal the conditions for achieving a competitive advantage in the fast-moving yet restricted environment in the marketplace.

References

Abernathy, W J (1978) The Productivity Dilemma: Roadblock to innovation in the automobile industry, Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore

Abernathy, W J, Clark, K and Kantrow, A (1983) Industrial Renaissance: Producing a competitive future for America, Basic Books, New York

Abernathy, F H, Dunlop, J T, Hammond, J H and Weil, D (1999) A Stitch in Time, Oxford University Press, New York

Alderson, W (1957) Marketing Behaviour and Executive Action, Richard D Irwin

Azuma, N (2001) The reality of Quick Response (QR) in the Japanese fashion sector and the strategy ahead for the domestic SME apparel manufacturers, Logistics Research Network 2001 Conference Proceedings, pp 11–20, Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh

Azuma, N (2002) Pronto moda Tokyo style: emergence of collection-free street fashion and the Tokyo–Seoul connection, International Journal of Retail and Distribution Management, 30 (3), pp 137–44

Azuma, N and Fernie, J (forthcoming) Changing nature of Japanese fashion: the role of Quick Response in improving supply chain efficiency, European Journal of Marketing, special issue on Fashion Marketing

Barney, J (1991) Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage, Journal of Management, 17 (1), pp 99–120

Besanko, D, Dranove, D and Shanley, M (2000) Economics of Strategy, 2nd edn, Wiley, New York

Bucklin, L P (1965) Postponement, speculation, and structure of distribution channels, Journal of Marketing Research, 2 (1)

Burt, S L, Dawson, J and Larke, R (2003) Inditex – Zara: rewriting the rules in apparel retailing, Conference Proceedings, 2nd Asian Retail and Distribution Workshop, UMDS Kobe, Japan

Chandra, C and Kumar, S (2000) Supply Chain Management in theory and practice: a passing fad or a fundamental change? Industrial Management and Data Systems, 100 (3), pp 100–13

Chimura, N (2001) Sengo Fashion Story (Post War Fashion Story), Heibonsha, Tokyo

Christopher, M (1997) Marketing Logistics, Butterworth Heinemann, Oxford

Christopher, M (1998) Logistics and Supply Chain Management, 2nd edn, Financial Times, London

Christopher, M and Juttner, U (2000) Achieving supply chain excellence: the role of relationship management, International Journal of Logistics: Research and Application, 3 (1), pp 5–23

Christopher, M and Peck, H (1998) Fashion logistics, in Logistics and Retail Management, ed J Fernie and L Sparks, Kogan Page, London Day, G (1994) The capabilities of market-driven organizations, Journal of Marketing, 58, pp 37–52

Deshpande, R (ed) (1999) Developing a Market Orientation, Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA

Deshpande, R, Farley, J U and Webster Jr, F E (1993) Corporate culture, customer orientation, and innovativeness in Japanese firms; a Quadrad analysis, Journal of Marketing, 57, pp 23–37

De Toni, A and Nassimbeni, G (1995) Supply networks: genesis, stability and logistics implications. A comparative analysis of two districts, International Journal of Management Science, 23 (4), pp 403–18

Dicken, P (1998) Global Shift: Transforming the world economy, 3rd edn, Paul Chapman, London

Dickerson, K (1995) Textiles and Apparel in the Global Economy, Prentice Hall, New Jersey

Dosi, G (1982) Technological paradigms and technological trajectories: a suggested interpretation of the determinants and directions of technical change, Research Policy, 11 (3), pp 147–62

Elg, U (2003) Retail market orientation: a preliminary framework, International Journal of Retail and Distribution Management, 31 (2), pp 107–17

Fernie, J (1994) Quick Response: an international perspective, International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Management, 24 (6), pp 38–46

Fernie, J (1998) Relationships in the supply chain, in Logistics and Retail Management, ed J Fernie and L Sparks, Kogan Page, London Fiorito, S S, Giunipero, L C and Oh, J (1999) Channel relationships and Quick Response implementation, Conference Paper, 10th International Conference on Research in the Distributive Trades, Stirling University

Fisher, M L, Raman, A and McClelland, A S (1999) Supply Chain Management at World Co. Ltd, World Co. Ltd, Tokyo

Forza, C and Vinelli, A (1996) An analytical scheme for the change of the apparel design process towards quick response, International Journal of Clothing Science and Technology, 8 (4), pp 28–43

Forza, C and Vinelli, A (1997) Quick Response in the textile–apparel industry and the support of information technologies, Integrated Manufacturing Systems, 8 (3), pp 125–36

Forza, C and Vinelli, A (2000) Time compression in production and distribution within the textile–apparel chain, Integrated Manufacturing Systems, 11 (2), pp 138–46

Giunipero, L C, Fiorito, S S, Pearcy, D H and Dandeo, L (2001) The impact of vendor incentives on Quick Response, International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, 11 (4), pp 359–76

Grant, R M (1991) Analysing resources and capabilities, in Contemporary Strategic Analysis: Concepts, techniques and applications, ed R M Grant, Blackwell, MAZ

Hines, T (2001) From analogue to digital supply chain: implications for fashion marketing, in Fashion Marketing, Contemporary Issues, ed T Hines and M Bruce, Butterworth Heinemann, Oxford

Hunter, A (1990) Quick Response in Apparel Manufacturing: A survey of the American scene, Textile Institute, Manchester

Inagaki, K (2003) Italia no Kigyouka Network (Entrepreneurs Networking in Italy), Hakuto-Shobo, Tokyo

Itami, H (1999) Ba no Dynamism (The Dynamics of Shared Space and Atmosphere), NTT Publishing, Tokyo

Jackson, T (2001) The process of fashion trend development leading to a season, in Fashion Marketing, ed T Hines and M Bruce, Butterworth Heinemann, Oxford

Jaworski, B and Kohli, A (1993) Market orientation: antecedents and consequences, Journal of Marketing, 57, pp 53–70

Kohli, A and Jaworski, B (1990) Market orientation: the construct, research propositions, and managerial implications, Journal of Marketing, 54, pp 1–18

Kohli, A and Jaworski, B (1999) Market orientation: the construct, research propositions, and managerial implications, in Developing a Market Orientation, ed R Deshpande, Sage, London

Kuhn, T (1970) The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL

Levin, R C, Klevorick, A K, Nelson, R R, and Winter, S G (1988) Appropriating the returns from industrial research and development, Brooking Papers on Economic Activity, 13 (2), pp 839–916

Levitt, T (1969) The Marketing Mode, McGraw-Hill, New York

Levitt, T (1983) The Marketing Imagination, Free Press, New York

Lewis, B R and Hawkesley, A W (1990) Gaining a competitive advantage in fashion retailing, International Journal of Retail and Distribution Management, 18 (4), pp 21–32

Lowson, B (1998) Quick Response for Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises: A feasibility study, Textile Institute, Manchester

Lowson, B, King, R and Hunter, A (1999) Quick Response: Managing supply chain to meet consumer demand, Wiley, New York

Mahoney, J T and Pandian, J R (1992) The resource-based view within the conversation of strategic management, Strategic Management Journal, 13 (5), pp 363–80

Maximov, J and Gottschlich, H (1993) Time–cost–quality leadership, International Journal of Retail and Distribution Management, 21 (4), pp 3–12

McGee, J and Johnson, G. (eds) (1987) Retail Strategies in the UK, Wiley, Chichester

Meijboom, B (1999) Production-to-order and international operations: a case study in the clothing industry, International Journal of Operations and Production Management, 19 (5/6), pp 602–19

Minami, C (2003) Fashion Business no Ronri – ZARA ni Miru Speed no Keizai (The logic in the fashion business – the impact of economies of speed from Zara experiences), Ryutsu Kenkyu, June, pp 31–42

Montgomery, C A and Wernerfelt, J M (1988) Diversification, Ricardian rents and Tobin’s Q, Rand Journal of Economics, 19, pp 623–32

Narver, J and Slater, S (1990) The effect of a market orientation on business profitability, Journal of Marketing, 54 (Oct), pp 20–35

Nukata, H (1998) Sangyo Shuseki ni Okeru Bungyo no Jyunansa (Flexible division of labour in industrial agglomerations), in Sangyo Shuseki no Honshitsu (The Essence of the Industrial Agglomeration), ed H Itami, S Matushima and T Kitsukawa,Yuhikaku, Tokyo

Ogawa, H (1998) Italia no Chusho Kigyo (SMEs in Italy), JETRO, Tokyo Ogawa, S (2000a) Innovation no Hassei Genri (The Process of Innovation), Chikura Shobo, Tokyo

Ogawa, S (2000b) Demand Chain Keiei (Demand Chain Management), Nippon Keizai Shimbunsha, Tokyo

Okamoto, Y (1994) Italia no Chusho Kigyo Senryaku (SMEs’ Strategies in Italy), Mita Shuppan Kai, Tokyo

Pelham, A J (1997) Market orientation and performance: the moderating effects of product and customer differentiation, Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing, 12 (5), pp 276–96

Penrose, E T (1955) The Theory of the Growth of the Firm, Wiley and Sons Ltd, New York

Pine II, B J (1993) Mass Customisation, Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA

Porter, M E (1985) Competitive Advantage, Free Press, New York Porter, M E (1996) What is Strategy? Harvard Business Review, 74, pp 61–78

Riddle, E J, Bradbard, D A, Thomas, J B and Kincade, D H (1999) The role of electronic data interchange in Quick Response, Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 3 (2), pp 133–46

Rumelt, R P (1984) Towards a strategic theory of the firm, in Competitive Strategic Management, ed R Lamb, Englewood Cliffs, Prentice Hall, NJ

Schnaars, S P (1994) Managing Imitation Strategies, Free Press, New York Schumpeter, J A (1934) The Theory of Economic Development: An inquiry into profits, capital, credit, interest, and the business cycle, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

Siguaw, J S, Simpson, P and Baker, T (1998) Effects of supplier market orientation on distributor market orientation and the channel relationship, Journal of Marketing, 63, pp 99–111

Siguaw, J S, Simpson, P and Baker, T (1999) The influence of market orientation on channel relationships: a dyadic examination, in Developing a Market Orientation, ed R Deshpande, Sage, London

Slater, S and Narver, J (1995) Market orientation and the learning organization, Journal of Marketing, 59, pp 63–74

Slater, S F and Narver, J C (1999) Research notes and communications: market-oriented is more than being customer-led, Strategic Management Journal, 20, pp 1165–68

Stalk, G. Jr and Hout, T M (1990) Competing Against Time, Free Press, New York

Stern, L, El-Ansary, A and Coughalan, A (1996) Marketing Channels, 5th edn, Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ

Takeishi, A (2001) Innovation no pattern (Patterns in innovation) in Innovation Management Nyumon (Fundamentals of Innovation Management), Hitotsubashi University Innovation Research Centre, Nihon Keizai Shimbunsha, Tokyo

Tamura, M (1975) Seni Oroshiuri-Sho no Keiei Kouritsuka no Houkou – Seni Oroshiuri-Sho no Kinou Bunseki Houkoku (The Direction towards Textiles and Apparel Wholesalers’ Efficient Management: An analysis on the function of textiles and apparel wholesale merchants), Osaka Chartered Institute of Commerce, Osaka

Tamura, M (1996) Marketing Ryoku (The Power of Marketing), Chikura Shobo, Tokyo

Tamura, M (2001) Ryutsu Genri (Principles of Marketing and Distribution), Chikura Shobo, Tokyo

Tamura, M (2003) Shijoushikou no Jissen Riron wo Mezashite (Towards an Operationalization of the Market Orientation Approach), University of Marketing and Distribution Science Monograph, no 15

Teece, D (1986) Profiting from technological innovation: implications for integration, collaboration, licensing and public policy, Research Policy, 15, pp 285–305

Von Hippel, E A (1988) The Sources of Innovation, Oxford University Press, New York

Weerawardena, J (2003) Exploring the role of market learning capability in competitive advantage, European Journal of Marketing, 37(3/4), pp 407–29

White, L (1982) The automobile industry, in The Structure of American Industry, 6th edn, ed W Adams, Macmillan, New York

Whiteoak, P (1994) The realities of quick response in the grocery sector a supplier viewpoint, International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Management, 29 (7/8), pp 508–19

Williams, J (1992) How sustainable is your advantage? California Management Review, 34, pp 1–23

Yahagi, T (1994) Convenience Store System no Kakushin-sei (Innovativeness of the Convenience Store System), Nihon Keizai shimbunsha, Tokyo

Yahagi, T (2001) Chain Store no Seiki ha Owattanoka (Has the chain store age ended?), Hitotsubashi Business Review, August, pp 30–43

Yahagi, T, Ogawa, K and Yoshida, K (1993) Sei–Han Tougo Marketing (Supplier–Retailer Integrated Marketing Approach), Hakuto Shobo, Tokyo

Yamashita, Y (1993) Shijo ni Okeru Ba no Kino (The role of ‘Ba’ in the marketplace), Soshiki Kagaku, 27 (1),pp 75–87

Yamashita, Y (1998) Discounter no Seisui (The rise and fall of discount stores), in Innovation to Gijutsu Chikuseki (Innovation and Technology Accumulation), ed H Itami, T Kagono, M Miyamoto and S Yonekura, Yuhikaku, Tokyo

Yamashita, Y (2001) Shogyo Shuseki no Dynamism (The dynamics of commercial accumulation), Hitotsubashi Business Review, August, pp 74–94

Preface

- Retail Logistics: Changes and Challenges

- Relationships in the Supply Chain

- The Internationalization of the Retail Supply Chain

- Market Orientation and Supply Chain Management in the Fashion Industry

- Fashion Logistics and Quick Response

- Logistics in Tesco: Past, Present and Future

- Temperature-Controlled Supply Chains

- Rethinking Efficient Replenishment in the Grocery Sector

- The Development of E-tail Logistics

- Transforming Technologies: Retail Exchanges and RFID

- Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) Systems: Issues in Implementation

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 119