Understanding Shared References

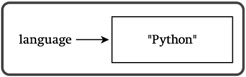

In Chapter 2, you learned that a variable refers to a value. This means that, technically, a variable doesn't store a copy of a value, but just refers to the place in your computer's memory where the value is stored. For example, language = "Python" stores the string "Python" in your computer's memory somewhere and then creates the variable language, which refers to that place in memory. Take a look at Figure 5.8 for a visual representation.

Figure 5.8: The variable language refers to a place in memory where the string value "Python" is stored.

To say the variable language stores the string "Python", like a piece of Tupperware stores a chicken leg, is not accurate. In some programming languages, this might be a good analogy, but not in Python. A better way to think about it is like this: A variable refers to a value the same way a person's name refers to a person. It would be wrong (and silly) to say that a person's name "stores" the person. Using a person's name, you can get to a person. Using a variable name, you can get to a value.

So what does all this mean? Well, for immutable values that you've been using, like numbers, strings, and tuples, it doesn't mean much. But it does mean something for mutable values, like lists. When several variables refer to the same mutable value, they share the same reference. They all refer to the one, single copy of that value. And a change to the value through one of the variables results in a change for all the variables, since there is only one, shared copy to begin with.

Here's an example to show how this works. Suppose that I'm throwing a hip, happening party with my friends and dignitaries from around the world. (Hey, this is my book. I can make up any example I want.) Different people at the party call me by different names, even though I'm only one person. Let's say that a friend calls me "Mike," a dignitary calls me "Mr. Dawson," and my Pulitzer Prize winning, supermodel girlfriend, just back from her literacy, fundraising world-tour (again, my book, my fictional girlfriend) calls me "Honey." So, all three people refer to me with different names. This is the same way that three variables could all refer to the same list. Here's the beginning of an interactive session to show you what I mean:

>>> mike = ["khakis", "dress shirt", "jacket"] >>> mr_dawson = mike >>> honey = mike >>> print mike ['khakis', 'dress shirt', 'jacket'] >>> print mr_dawson ['khakis', 'dress shirt', 'jacket'] >>> print honey ['khakis', 'dress shirt', 'jacket']

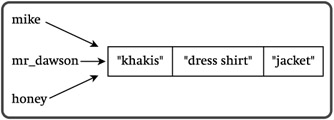

So, all three variables, mike, mr_dawson, and honey, refer to the same, single list, representing me (or at least what I'm wearing at this party). Figure 5.9 helps drive this idea home.

Figure 5.9: The variables mike, mr_dawson, and honey all refer to the same list.

This means that a change to the list using any of these three variables will change the list they all refer to. Back at the party, let's say that my girlfriend gets my attention by calling "Honey." She asks me to change my jacket for a red sweater she knitted (yes, she knits too). I, of course, do what she asks. In my interactive session, this could be expressed as follows:

>>> honey[2] = "red sweater" >>> print honey ['khakis', 'dress shirt', 'red sweater']

The results are what you would expect. The element in position number 2 of the list referred to by honey is no longer "jacket", but is now "red sweater".

Now, at the party, if a friend were to get my attention by calling "Mike" or a dignitary were to call me over with "Mr. Dawson," both would see me in my red sweater, even though neither had anything to do with me changing my clothes. The same is true in Python. Even though I changed the value of the element in position number 2 by using the variable honey, that change is reflected by any variable that refers to this list. So, to continue my interactive session:

>>> print mike ['khakis', 'dress shirt', 'red sweater'] >>> print mr_dawson ['khakis', 'dress shirt', 'red sweater']

The element in position number 2 of the list referred to by mike and mr_dawson is "red sweater". It has to be since there's only one list.

So, the moral of this story is: be aware of shared references when using mutable values. If you change the value through one variable, it will be changed for all.

However, you can avoid this effect if you make a copy of a list, through slicing. For example:

>>> mike = ["khakis", "dress shirt", "jacket"] >>> honey = mike[:] >>> honey[2] = "red sweater" >>> print honey ['khakis', 'dress shirt', 'red sweater'] >>> print mike ['khakis', 'dress shirt', 'jacket']

Here, honey is assigned a copy of mike. honey does not refer to the same list. Instead, it refers to a copy. So, a change to honey has no effect on mike. It's like I've been cloned. Now, my girlfriend is dressing my clone in a red sweater, while the original me is still in a jacket. Okay, this party is getting pretty weird with my clone walking around in a red sweater that my fictional girlfriend knitted for me, so I think it's time to end this bizarre yet useful analogy.

One last thing to remember is that sometimes you'll want this shared-reference effect, while other times you won't. Now that you understand how it works, you can control it.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 194