The Effects of an Enterprise Resource Planning System (ERP) Implementation on Job Characteristics – A Study using the Hackman and Oldham Job Characteristics Model

Overview

Gerald Grant

Carleton University, Canada

Aareni Uruthirapathy

Carleton University, Canada

Copyright © 2003, Idea Group Inc. Copying or distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of Idea Group Inc. is prohibited.

Abstract

As organizations undertake the deployment of integrated ERP systems, concerns are growing about its impact on people occupying jobs and roles in those organizations. The authors set out to assess the impact of ERP implementation on job characteristics. Using the Hackman and Oldham Job Characteristics Model as a basis, the study assesses how ERP affected work redesign and job satisfaction of people working in several Canadian federal government organizations.

Introduction

Work redesign occurs whenever a job changes, whether because of new technology, internal reorganization, or a whim of management (Hackman & Oldham, 1975). In order to adopt new technologies, companies have to introduce significant organizational changes which require an overall work redesign. Many organizations use work redesign as a tool to introduce planned change: whether it is an organizational change or a technological change, work must be redesigned to introduce new work routines.

During the mid 1990s, many medium and large companies started implementing enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems from companies such as Baan, PeopleSoft, SAP, and Oracle. Survey results based on data collected from 186 companies from a broad cross section of industries that implemented SAP highlighted eight important reasons why organizations initially chose to implement SAP. These reasons were the following: to standardize company processes, to integrate operations or data, to reengineer business processes, to optimize supply chain, to increase business flexibility, to increase productivity, to support globalization, and to help solve year 2000 problems (Cooke & Peterson, 1998).

An ERP implementation is not only an IT change but also a major business change. It is critical for organizations and their employees to understand this, because only then will the issue of communicating change and its effects to employees attain equal standing with the implementation of technical changes. ERPs have embedded processes, which impose their own logic on a company's strategy, organization and culture. Companies have to reconcile the technological imperatives of an enterprise system with the business needs of the organization (Davenport, 1999).

During an enterprise system implementation, organizations have to reallocate human resources to the project. Employees must be trained in new skills and work alongside outside consultants to transfer knowledge about the systems and the process (Welti, 1999). With a process system, departments located separately are encouraged to move closer together so that managers can work with the process system more effectively. Structural reorganization allows easy interaction between different functional groups. For example, all those involved in order fulfillment are located together to share the same facility and get a better view of the entire process. Top management's strong commitment is critical for a successful implementation of an ERP system. The new organizational structure allows top management to have a stronger influence on the organization's integrated functions. An enterprise system also has a paradoxical impact on a company's organizational culture (Davenport, 1999); an integrated system increases the pressure for the eradication of strictly functional organizational culture. A new, more collaborative, organizational culture is expected to emerge as the functional units work through an integrated system.

In this chapter, we explore the impact of ERP implementation on work redesign. Two questions motivate this research: (1) To what extent does ERP implementation lead to work redesign? (2) What is the impact of ERP-initiated work redesign on employee job satisfaction? We address these questions by investigating the experience of organizations in the Canadian Federal Government that implemented SAP R/3 using the Hackman-Oldham (1975) as a theoretical lens. The rest of the chapter will proceed as follows: We begin with a general discussion of theories of work redesign followed by a brief overview of the Hackman and Oldham Job Characteristics Model. We then discuss the Job Characteristics Model and ERP-initiated work redesign. Following an overview of the research method, we present the results of the survey and interviews. After a brief discussion, we highlight some implications for organizations adopting ERP systems.

Theories of Work Redesign

The implementation of an ERP system such as SAP R/3 can have a dramatic effect on the style, structure, and culture of the organization. When this occurs, work redesign is inevitable. Employees, who have undergone training with the process system and acquired greater knowledge interacting with it, need tasks assigned that use these skills. Employees who find it difficult to work with the enterprise system need non-system jobs assigned to them. Performance evaluation and career advancement should reflect the organizational changes. Work redesign around the process system should not only increase the efficiency of the company but also provide the organizational participants with enriched work. Task design should result in work itself providing the employees with the motivation to perform well, and increasing on-the-job productivity. Most of all, jobs need to be designed in such a way that they provide employees enjoyable work by putting their skills and talents to use.

How can individuals be motivated at work? Researchers in human behavior science have been trying to answer this question for a long time. It has been a difficult question to answer because individuals are different from one another. In the mid 1970s, researchers considered work redesign as the solution to motivating employees at work. Case studies of successful work redesign projects indicate that work redesign can be an effective tool for improving both the quality of the work experience of employees and their on-the-job productivity (Hackman, 1975). A number of researchers have studied work redesign over the years. The table below provides an outline of the theories espoused and their basic assumptions.

|

Researchers |

Theory |

Basic Assumptions |

|---|---|---|

|

Frederick Herzberg (1959) |

Two Factor Theory |

Hygiene factors are necessary to maintain a reasonable level of satisfaction in employees, which are extrinsic and are related to the job context. They are pay, benefits, job security, physical working conditions, supervision policies, company policies and relationships with co-workers. Motivating factors are intrinsic to the content of the job itself. These are factors such as achievement, advancement, recognition and responsibility. It is these factors that bring job satisfaction and improvement in performance. |

|

Douglas McGregor (1960) |

Theory X and Theory Y |

McGregor's Theory X assumes that employees are lazy and unwilling to produce above the minimum requirements. By contrast, Theory Y assumes that people are not by nature passive or resistant to organizational objectives. The essential task of management is to arrange organizational operations in such a way that employees achieve their own goals by directing their efforts towards organizational objectives. |

|

Turner and Lawrence (1965) |

Requisite Task Attributes Model |

They used six requisite task attributes, such as variety, required interaction, knowledge and skill, autonomy, optional interaction and responsibility to calculate a requisite task attribute index (RTA). They found strong links between attendance, worker's involvement and attributes of the work. |

|

William Scott (1966) |

Activation Theory |

When jobs are dull or repetitive it leads to low levels of performance because dull jobs fail to activate the brain. However, when jobs are enriched, it leads to a state of activation and enhances productivity. |

Hackman and Oldham Job Characteristics Model

In 1975, Hackman and Oldham proposed a comprehensive Job Characteristics Model for work redesign in modern organizations.

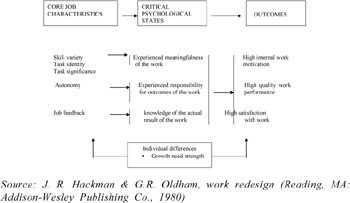

Hackman and Oldham (1975) argued that task dimensions could represent the motivating potential of jobs and proposed that individuals would be motivated towards their job, and feel job satisfaction, only when they experienced certain psychological states. They identified these critical psychological states: experienced meaningfulness of work, experienced responsibility for outcomes of the work, and knowledge of actual results of the work activities. The belief is that the positive effect created by the presence of these psychological states reinforces motivation and serves as an incentive for continuing to do the task. In order to produce these psychological states, a job should have certain core characteristics. Hackman and Oldham found that skills variety, task identity and task significance facilitated experienced meaningfulness at work; the level of autonomy in a job increases the feeling of personal responsibilities for work outcomes. They also found that when a job has good feedback, it provides the employee with increased knowledge of the actual results of the work activities. The Job Characteristics Model suggested that growth need strength (GNS) is a moderator, which affects the employees' reactions to their work. Hackman and Oldham used a job diagnostic survey (JDS) to test their Job Characteristics Model, obtaining data from 658 employees working on 62 different jobs in seven organizations.

Figure 1: Hackman and Oldham Job Characteristics Model (1975)

Research Background

Selected Canadian Government organizations have implemented SAP R/3 software as the enterprise system to replace their legacy systems. Before the SAP implementation, the Federal Government organizations had information systems that their in-house IT departments built and managed. With the decision to use the SAP system, there was limited time to prepare the necessary foundation for a successful implementation. The SAP implementation brought significant changes into these organizations. SAP project teams were formed in every functional unit and a speedy implementation began. These project teams worked alongside outside SAP consultants and spent a great deal of time configuring the system to suit the particular needs of the industry. Functions decentralized across Canada had to be centralized, resulting in the splitting, merging and re-alignment of departments and the establishment of new groups. Employees received new jobs with new roles and responsibilities. Employees moved from one location to another so they could work closely with peers from other functional units. The normal routines of work were disturbed, which frustrated many employees who struggled to familiarize with the new process system. When the process was centralized, jobs moved from different parts of Canada to one location. During a normal hiring process, employers match the employees' skills, abilities and responsibilities with the job profile; however, such matching did not take place when reassigning jobs during SAP implementation, as there was insufficient time to do so.

Research Method

An exploratory research carried out in nine government organizations with forty-seven SAP users attempted to establish how work redesign involving SAP systems took place. A questionnaire containing questions based on the components of the Job Characteristics Model was sent to all federal government organizations where SAP system was implemented. The overriding objective of this research was to develop a clear understanding of how the implementation of an Enterprise Resource System generated work redesign in organizations, and whether such work redesigns provided the organizational participants with job satisfaction. Thus, the survey tried to get answers for two questions: "To what extent does enterprise resource planning implementation lead to work redesign?" and "What is the impact of ERP initiated work redesign on employee job satisfaction?"

Results

We use the job characteristics contained in the Hackman and Oldham model to present and discuss the results of the surveys and interviews.

Skill Variety

The research found that 75 percent of the respondents agreed that they used more skills with SAP than they did before. With the legacy systems, they had only to understand a limited number of processes and perform them repetitively; with SAP, they had to be very analytical and clearly understand their part in the whole process. SAP users employed a variety of skills and talents when they tried new processes and deal with the software. However, some managers were of the view that using more skills and talents largely depended on the set of skills the employees possessed. Employees who had stronger computer skills would use them much more than would those who were less computer literate.

Task Identity

When asked about task identity, 55 percent of the sample agreed that they knew their work outcomes in the process system. An employee working with the accounting module and in charge of the general ledger will be responsible for creating, changing and maintaining the ledger. The nametag attached to each SAP transaction allows employees to identity how their work interacts with the whole organization, thus individual employees know who is doing what and whether data is correctly processed. The system will also detect errors made by individual employees. However, there are security features, such as role-based authorizations, protocols and digital signatures, which prevent them from accessing all information. Some managers argue that these features considerably reduce task identity for employees.

Autonomy and Task Significance

More than 80 percent of those who answered the questionnaires agreed that the process system provided employees with autonomy and independence at work. An integrated system provides the users with the necessary information to perform their work. When a new transaction takes place, the information is instantly available company-wide. Managers prepare reports and allow their employees to do their own queries and to retrieve appropriate data. Some managers, however, raised doubts about whether the process system provided employees with autonomy, since they considered SAP to be a highly standardized system that forced individual employees to work within a given framework with little flexibility. For example, a receiver must immediately enter relevant data into the system upon receipt of products. The employee cannot wait until the next day, because that causes many mismatches in the system. In an integrated system, every interaction becomes important, with even small transactions having a large impact on the organization. This may be the reason why over 55 percent of the respondents felt that their work with the SAP system was more significant to the organization than it was before. With the SAP system, individuals need to know what is driving the system and to where it is being driven, because it depends on individuals to provide accurate and timely data. For example, before the integrated system, a payroll clerk counted the time for each employee and passed the information to the compensation section clerk; however, in the process system, this data drives the whole system, making the payroll clerk's task more significant.

Feedback from Job and Supervisor

When asked about feedback from the job itself, more than 60 percent of the sample said that they often received feedback from their job. However, the feedback appeared to be more from other individuals rather than directly from the system. Some believe that when you deal with the system on a day-to-day basis with different people doing different activities, one individual may identify and communicate mistakes made by another. An integrated system such as SAP facilitates this quick error detection. In this study, only 40 percent of the sample indicated that they received feedback from their supervisors; managers set the task parameters, and it was up to individual employees to complete the job without having to report back to their supervisors because the transaction records are all in the process system. Because everyone who was involved in getting the job done knew who was doing what and the progress of the task, there was no immediate need for a formal feedback. Organizations participating in the study were working on setting up formal feedback channels as employees adapt to the process system.

On average, 60 percent of the sample agreed that the process system provided them with an enriched job with characteristics such as autonomy, task identity, task significance, skill variety, and feedback from both the job and the supervisor. Some job characteristics, specifically autonomy, task identity and task significance were stronger than others were.

Meaningfulness in Work

In this research, more than 80 percent of the sample showed that they experienced meaningfulness in their work with the SAP system. This sense of accomplishment came when individuals overcame the challenges presented by the process system and learned to work around the constraints of the system. The process system also allowed users to work with peers from other departments; they were able to compare what they were doing and learn from each other, discovering correct functionality and developing the necessary solutions for problems. These experiences were meaningful and employees felt satisfied with their work performance.

Of all the variables suggested by the Job Characteristics Model, only task significance had significant correlation with experienced meaningfulness, demonstrating that this group of SAP users experienced meaningfulness when they felt that their job was significant to the whole organization. On the other hand, feedback from the job and supervisor had a moderate rating individually but correlated significantly with experienced meaningfulness (although not predicted by the model). From this, we reason that, for this particular sample of SAP users, task significance led to experienced meaningfulness and that, even when they received moderate levels of feedback from job and supervisor, they still experienced meaningfulness.

Experienced Responsibility

According to the model, autonomy leads to the psychological state of experienced responsibility. The correlation between these two variables was very poor in this study and not as predicted by the Job Characteristics Model; however, other job dimensions task identity and task significance - correlated more strongly with experienced responsibility. We conclude that, for this group of SAP users, experienced responsibility did not come from the level of independence they had, but from other job dimensions such as task significance and task identity.

Knowledge of Task Outcomes

Job and supervisor feedback provide employees with knowledge of task outcomes. In this research, there was a significant correlation between knowledge of results and feedback from the job, this being the only job dimension that predicted knowledge of task outcomes suggested by the job characteristic model. The system provides users with periodic feedback on transactions, allowing SAP users to do things faster and better since employees immediately know the results of their work. However, there was no significant correlation between knowledge of results and feedback from the supervisor, further supporting the low rating indicated for feedback from supervisor. Although not predicted by the model, other job dimension variables such as skill variety and task identity had strong relationships with knowledge of outcomes. These findings suggest that, for this particular sample of SAP users, skill variety and task identity provided them with knowledge of their work outcome as much as feedback from the job. Nevertheless, the nature of the SAP system does not provide direct results from work - it only contains and provides updated information about the many transactions that take place within an organization.

Growth Need Strength

In theory, growth need strength plays a mediating role between job dimensions and the affective outcomes. This moderating effect was not found in our research. The participants who had high growth need and those who had lower growth need both reacted the same way to job dimensions. Nor was there any difference in their psychological states. When the SAP system was implemented, it collapsed all the working levels to support the software. Employees from all levels were taken from their jobs and put to work on the process system. These organizations did not have clear career advancement paths in place to identify talent with the process system. In many federal organizations, personnel turnover during and after SAP implementation was significant. These may be the reasons why growth need did not influence how individuals reacted to their jobs with the process system.

Discussion and Implications

The analysis of the five core job characteristics and the three critical psychological states in the Job Characteristic Model provided a snapshot as to how users felt about their new jobs when working with a process system such as SAP R/3. Initially, working with the SAP system was not motivating for employees in these organizations, as they did not understand how their jobs were going to change and could not perform their tasks effectively. They struggled to carry out their responsibilities. When work units went "live" with the system, the error rates were generally high. However, as time passed and SAP users became more comfortable with the integrated system and got to know their exact roles and responsibilities, they became more motivated in their jobs. The whole work environment forced employees to change their behavior towards work; the legacy systems disappeared as the new system took over. Work redesign initiated by the process system provided employees with opportunities for personal growth by giving them an opportunity to work with world-class integrated system technology and acquire skills that increase their value in the labor market. In most organizations, after a year of SAP adoption, employees are happier with the system and complaints have reduced tremendously. As employees successfully overcame the constraints of the process system, they experienced more satisfaction at work.

Implications for Organizations Adopting ERP System

There are some steps companies can take to improve the transition from the legacy system to the ERP system. First, organizations need to have in place strategies for managing IS enabled change during each phase of the implementation. These strategies will favorably affect employees and give them information on how their jobs are going to change, reducing the level of resistance. When management decides to implement ERP, they should communicate this decision to all organizational levels. Change strategies should emphasize that the process system implementation is not an IT change, but a business change. Employees need to understand the business objectives the organization is trying to achieve through implementing a process system. Change agents should be working with all functional units to address the concerns of the employees who will undergo major work changes. They should have good communication and negotiation skills to be able to influence the mindset of the employees and create a favorable response to the process system.

Second, organizations should ensure that there is a strong project management process in place. When organizations implement many SAP modules at the same time, each module should have a subproject manager. There should be a clear structure in assigning work to people within the process system. When assigning responsibilities, it is important to match job profiles with skills, talents and previous experience. Management should evaluate employees and discuss with each individual how his or her job is going to change and whether the individual is willing to take up new responsibilities. They should also explain the guidance and help that will be available for individuals to cope with the changes. In many government organizations, supervisors spend considerable time testing the modules; actual users should also participate in the testing process to allow them to understand the process system and give them opportunities to try transactions in different ways.

Third, a SAP implementation budget should allocate sufficient funds for SAP training. The prospective user requires training in the particular module in which he or she is going to work. Some government organizations used the concept of training the trainers; a group of employees received training and then they trained other users. This type of training is not suitable for a complex system like SAP. In some Canadian federal government organizations some departments received more training than others did; this is also not suitable for an integrated system because all departments should have the expertise for a successful adoption of the process system - all departments need equal training. Organizations often cut short the training phase when they have only a short time frame in which to implement the system; this should not be the case. Users should know how to operate the system in order to work comfortably with it; they need clear manuals that teach them about the system. These manuals should document the many processes in the system, thereby reducing some of the difficulties the users encounter and facilitating self-learning. SAP users also need post-implementation training to allow them to find solutions to their own unique problems.

Finally, when organizations hire SAP consultants, they must take the time to investigate whether the consultants have the expertise and knowledge in particular industry practices. Hiring consultants with SAP knowledge alone is not enough to solve the day-to-day problems of SAP users, as the consultants must understand the internal business environment of the organization. In addition, the services of consultants should be engaged in different phases of the SAP implementation. In some of the organizations where this research was conducted, consultants were available only at the initial stages of SAP implementation; when the SAP users got to know the system and had questions and doubts, there were no consultants to help them - the employees had to spend more time in figuring things out for themselves. Organizations need control over what the consultants are doing, periodically auditing the services of the consultants and making sure they transfer knowledge to the users.

Conclusions

Redesigning work in organizations is a very challenging undertaking because every individual needs a job profile that matches his or her skills and knowledge. Even if one job is changed in an organization, many of the interfaces between that job and the related ones need to be changed also, creating a chain of changes. When an organization implements an enterprise planning system such as SAP R/ 3, work has to be redesigned extensively. It is a challenging task for managers to allocate work and for employees to get used to new ways of doing the job. Paying attention to people issues is critical element in achieving success from an enterprise system.

References

Cooke, P. D., & Peterson, J. W. (1998). SAP implementation: Strategies and results. New York: The Conference Board Publication, Inc.

Davenport, T. (1998), Putting the enterprise into the enterprise systems. Harvard Business Review, 76 (4), pp. 121–131.

Hackman. J.R. (1975). On the coming demise of job enrichment. In E.L. Cass & F.G. Zimmer, (eds.), Man And Work In Society. New York: Van Nostrand-Reinhold.

Hackman, J.R., & Oldham, G.R. (1975). Development of the job diagnostic survey. Journal of Applied Psychology, 60 (2), pp. 159–170.

Hackman, J.R., & Oldham, G.R. (1976). Motivation through the design of work: Test of a theory. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 16 (2), pp. 250–279.

Hackman, J.R., & Oldham, G.R. (1980). Motivation through the design of work. In Work Redesign (pp. 71–99). MA: Addison-Wesley.

Hammer, M. & Stanton, S. (1999). How process enterprises really work. Harvard Business Review, 77(6), pp. 108–118.

Herzberg, F., Mausner, B., & Bloch-Snyderman, B. (1959). The motivation to work (2nd Ed.) New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Mayo, E. (1945). The social problems of an industrial civilization. Boston: Harvard University Press.

McGregor, D. (1966). Leadership and motivation. MA: The M.I.T Press.

Scott, W. E. (1966). Activation theory and task design. In Organizational behavior and human performance (pp. 3–30).

Turner, A.N., & Lawrence, P. R. (1965). Industrial jobs and the worker. Boston, MA: Harvard University, Graduate School of Business Administration.

Welti, N. (1999). Successful SAP R/3 implementation: A practical management of ERP project. Addison-Wesley.

Part I - ERP Systems and Enterprise Integration

- ERP Systems Impact on Organizations

- Challenging the Unpredictable: Changeable Order Management Systems

- ERP System Acquisition: A Process Model and Results From an Austrian Survey

- The Second Wave ERP Market: An Australian Viewpoint

- Enterprise Application Integration: New Solutions for a Solved Problem or a Challenging Research Field?

- The Effects of an Enterprise Resource Planning System (ERP) Implementation on Job Characteristics – A Study using the Hackman and Oldham Job Characteristics Model

- Context Management of ERP Processes in Virtual Communities

Part II - Data Warehousing and Data Utilization

- Distributed Data Warehouse for Geo-spatial Services

- Data Mining for Business Process Reengineering

- Intrinsic and Contextual Data Quality: The Effect of Media and Personal Involvement

- Healthcare Information: From Administrative to Practice Databases

- A Hybrid Clustering Technique to Improve Patient Data Quality

- Relevance and Micro-Relevance for the Professional as Determinants of IT-Diffusion and IT-Use in Healthcare

- Development of Interactive Web Sites to Enhance Police/Community Relations

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 174