Enterprise Services: System.EnterpriseServices

| Modern multitier applications often locate the bulk of their business logic in the middle tier. Much of the time, writing this logic with a technology such as ASP.NET is perfectly adequate. In some cases, however, especially for applications that need to be very scalable and require features such as distributed transactions, more is required. Prior to .NET, the Microsoft technology that provided these services was known as COM+. With the advent of the .NET Framework, those services are still available to CLR-based applications. In fact, the services themselves haven't changed much at all, but two things about them have: how they're accessed and what they're called. Now known as Enterprise Services, all of the traditional COM+ services for building robust, scalable applications are usable by applications written on the .NET Framework.

What Enterprise Services ProvidesFor a class to use Enterprise Services, that class must inherit from EnterpriseServices.ServicedComponent. Because of this, a class using these services is referred to as a serviced component. Serviced components have access to the full range of what Enterprise Services provides, including the following:

One of the innovations brought by COM+ (or more correctly, by Microsoft Transaction Server, the original incarnation of this technology) was the ability to control what services a component received by setting attributes in a configuration file. In the .NET Framework, however, attributes are supported directly. Every assembly can have extra metadata represented as attributes, and attribute values can be set in the source code of a CLR-based application. This built-in support for attributes matches well with how COM+ provides its services, and so an Enterprise Services developer specifies what services should be used by including attributes directly in his code. And because it's sometimes useful to be able to change a component's attributes after the assembly that contains it has been installed, it's still possible to set or modify a deployed component's attributes if desired.

Here's a simple VB.NET class that shows how attributes can be used to control the use of Enterprise Services transactions: <Transaction(TransactionOption.Required)> _ Public Class BankAccount Inherits ServicedComponent <AutoComplete()> _ Public Sub Deposit(Account As Integer, _ Amount As Decimal) ' Add Amount to Account End Sub <AutoComplete()> _ Public Sub Withdrawal(Account As Integer, _ Amount As Decimal) ' Subtract Amount from Account End Sub End Class This class, called BankAccount, inherits from Serviced Component, as is required for any class that wishes to use Enterprise Services. The class definition is also preceded with an attribute indicating that this class uses the Required setting for transactions. This means that whenever a client calls one of the class's methods, Enterprise Services will automatically wrap the work done by that method in the all-or-nothing embrace of a transaction.

The two methods in this simple class, Deposit and Withdrawal, each begin with the AutoComplete attribute (and since this is just an example, the code for these methods is omitted). This attribute indicates that if the method returns an exception, the serviced component will vote to abort the transaction of which it's a part. If the method completes normally, however, this component will vote to commit the transaction to which it belongs. Note that different attributes are applied at different levels. The Transaction attribute, for example, can be applied only to a classit can't be set per methodwhile AutoComplete can be applied only on a per-method basis. If the developer of this application wished to add a method to check the balance, she might well choose to put this method in some other class. Adding it to the BankAccount class would require the method to use a transaction, which isn't generally necessary for this kind of simple read operation.

Many other attributes are available for controlling aspects of a serviced component's behavior. For example, the JustInTime- Activation attribute allows turning just-in-time activation on and off (although this feature is automatically turned on for classes that use transactions), while the ObjectPooling attribute controls whether pooling is used and, if it is, how large the pool will be. Other available attributes set application-wide options such as the name of the application.

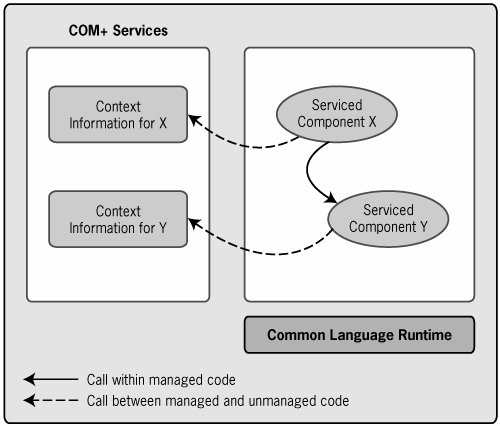

Enterprise Services and COM+Unlike most of the .NET Framework, the code that provides COM+ services was not rewritten as managed code. Instead, the classes in System.EnterpriseServices provide a wrapper around the existing implementation that allows managed objects access to these services. In spite of this, serviced components are able to use those services without leaving the managed environment. As Figure 7-5 shows, key COM+ services such as transactions are provided using context information maintained by COM+ itself in unmanaged code. When this context is accessed, such as when a serviced component votes to commit or abort a transaction, that request flows across the boundary between managed and unmanaged code. Interactions among serviced components, however, remain completely within the managed environment provided by the CLR. Since crossing into unmanaged code incurs a slight performance penalty, this ability to remain almost entirely within the managed space is a good thing. Figure 7-5. COM+ maintains context information for serviced components, allowing it to provide services across the managed/unmanaged boundary.

An important part of standard COM+ is an interface called IObjectContext that contains fundamental methods for components to use. Perhaps the most important of these are SetComplete and SetAbort, the two methods that allow a component to explicitly cast its vote in a transaction. In Enterprise Services, these same methods are available through a class called ContextUtil. If a transactional method wishes to control its commitment behavior directly, it can do so by calling these methods.

Enterprise Services also has a few more artifacts of its foundation in unmanaged code. For example, when a serviced component is accessed remotely, that access relies on DCOM rather than on .NET Remoting. Similarly, serviced components must have entries in the Windows registry, like traditional COM+ components but unlike other .NET classes. These entries can be created and updated automatically by the Enterprise Services infrastructurethere's no need to create them manuallybut requiring them at all betrays this technology's COM foundations.

Enterprise Services is an important part of the .NET Framework. While it's used by only a minority of applications, the services it provides significantly simplify the lives of the people who create those applications. And while its implementation as a veneer on the old COM+ introduces some messiness, this technology nevertheless succeeds in bringing these essential services into the .NET world.

|

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 67