Understanding the Strategic Positions

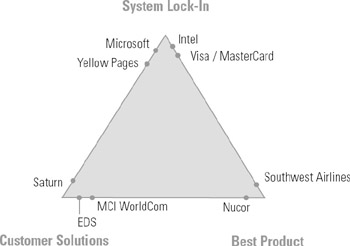

We can see the distinct nature of the three strategic positions by examining some companies that share the same outstanding business success but have achieved their high performance through strikingly different strategies and draw on fundamentally different sources of profitability (see figure 8.3).

Figure 8.3: Options for Strategic Positioning

Best-Product Position

Nucor Corporation is the fourth largest steel producer in the United States and the largest minimill producer. The objective of its classic best-product strategy is to be the lowest-cost producer in the steel industry. Its costs are $40 to $50 per ton less than those in the modern, fully integrated mills. Its sales per employee are $560,000 per year, compared to an average $240,000 for the industry. It has achieved this performance through a single-minded focus on product economics. Nucor's CEO John Correnti attributes 80 percent of its low-cost performance to a low-cost culture and only 20 percent to technology. In fact, during Nucor's boom years, between 1975 and 1986, twenty-five of its minimill competitors were closed or sold. Metrics reinforce this low-cost culture. Throughout the corporation, there is a strong alignment between the objectives and metrics critical to the strategy, namely, to be low-cost, and to the measurements and incentives for teams and individuals.

Nucor's financial performance resulting from this strategy is extraordinary. Before new management took over Nucor in 1966, the company was worth $13 million in market value. Thirty-two years later, this management and the processes it employed took Nucor to $5 billion in market value or 35 percent compounded growth—a spectacular result in the steel industry.

Southwest Airlines is another example of phenomenal performance through a best-product strategy. It relentlessly focuses on product economics and drives to cut product costs, sometimes reducing the scope and eliminating features from its service in the process. For example, it does not offer baggage handling, passenger ticketing, advance reservations, or hot food.

The activities that Southwest continues to perform it does differently. It emphasizes shuttle flights that efficiently utilize an aircraft on repeated trips between two airports, rather than using the hubs and spokes of the full-service carriers. It concentrates on the smaller and less congested airports surrounding large cities. It exclusively uses the Boeing 737, rather than the diverse fleets of the established carriers, thus reducing the costs of maintenance and training.

New companies may have an advantage over existing firms in originating radically new strategic positions founded on low cost because they may find it easier to redefine activities. Existing firms have embedded systems, processes, and procedures that are often obstacles to change and normally carry a heavy cost infrastructure. Many successful small companies have penetrated well-established industries and promptly reached a position of cost leadership in a more narrowly defined product segment, as in the cases of Nucor and Southwest, Dell and Gateway in personal computers, and WilTel in telecommunications. All these companies have had the same pattern: They narrowed the scope of their offering relative to the incumbents, they eliminated some features of the product, and they collapsed the activities of the value chain by eliminating some and outsourcing others. They perform the remaining activities differently, for either cost or product differentiation.

Customer Solutions Position

This competitive position reflects a shift in strategic attention from product to customer—from product economics to customer economics and the customer's experience.

Electronic Data Systems (EDS) is a clear example of a customer solutions provider. EDS has achieved prominence in the data processing industry by singularly positioning itself as a firm that has no interest in individual hardware or software companies. Its role is to provide the best solutions to cover total information needs, regardless of the components' origins. In the process, it has built a highly respected record by delivering cost-effective and tailor-made solutions to each customer. EDS has completely changed the perception of how to manage IT resources. While once IT was regarded as the brain of the company and every firm developed its own strong, internal IT group, now IT outsourcing is commonplace and even expected.

As a customer solutions provider, EDS measures its success by how much it improves the customer's bottom line or how it enhances the customer's economics. Typically, it goes into an organization that is currently spending hundreds of millions of dollars annually and delivers significant savings while, at the same time, enhancing the firm's current IT capabilities. This achievement is important in an industry that is cost-sensitive, rapidly changing, and extremely complex and sophisticated. EDS achieves these gains by extending the scope of its services to include activities previously performed by the customer. By focusing on IT, operations scale, and experience relative to the customer, it can offer services at a lower cost and/or higher quality than the customers themselves can.

MCI WorldCom provides a contrasting example of a customer solutions position. Where EDS has built value by "vertically" expanding its service scope into activities previously performed by the customer, MCI WorldCom is an almost pure example of expanding "horizontally" across a range of related services for the targeted customer segment, or bundling. It bundles the services together to reduce complexity for the customer. The customer benefits from a single bill, one contact point for customer service and sales, and potentially a more integrated, highly utilized network, but the products are the same. MCI WorldCom benefits through higher revenue per customer and longer customer retention, because it is harder to change vendors, and through lower-cost customer service and sales. Clearly, MCI WorldCom is following a strategy that is changing the rules of competition in the telecom industry and drawing on new sources of profitability. It is shifting the dimension of competitive advantage from product share to customer share.

Saturn, another example of the customer solutions position, is one of the most creative managerial initiatives in the past ten years. It abandoned a focus on products and turned its attention to changing the customer's full life-cycle experience. Saturn deliberately decided to design a car that would produce a driving experience close to the Toyota Corolla or the Honda Civic. It satisfied owners of these Japanese cars and therefore wanted to make the transition as easy as possible. Inherently, Saturn abandoned the best-product strategy and decided to create a product that was no different from the leading competition.

Instead, Saturn redefined the terms of engagement with the customer at the dealership. As any American buyer knows, purchasing a car can be unpleasant, subject to all kinds of uncomfortable pressures. Saturn targeted its dealers from a list of the top 5 percent of dealers in the United States, regardless of the brands they represented. Saturn offered extraordinary terms, which required a major commitment from the dealers to learn the Saturn culture and to make multimillion-dollar investments in the dealership.

First, and not just symbolically, Saturn changed the name "dealer", with the implicit connotation of negotiation and haggling, to "retailer", which connotes loyalty and fairness. Next, it instituted a no-haggling policy. Every car, and every accessory in the car, had a fixed price throughout the United States. In fact, the dealers educated customers on the features and price of the car and how they compared to competitors. Saturn also established a complete rezoning and expansion of retailer areas, thus limiting competition and allowing for more effective use of a central warehouse that a circle of Saturn dealers could share to lower inventory and costs. Additionally, it broke with tradition in the auto industry by offering a remarkable deal: "Satisfaction guaranteed, or your money back, with no questions asked". Saturn also implemented, for the first time, a "full car" recall. It replaced the complete car, not simply a component, and issued the recall within two weeks of finding symptoms of the problem.

Not surprisingly, customer response was overwhelming, creating what has become a cult among Saturn owners and thus giving Saturn the highest customer satisfaction rating in the industry—a phenomenal accomplishment for a car that retails for about one-fourth the price of luxury cars. Saturn's most powerful advertising campaign became the "word of mouth" from pleased customers, proving that focusing on the customer can be as strong a force in achieving competitive advantage as focusing on the product.

System Lock-in Position

In the system lock-in position are companies that can claim to own de facto standards in their industry. These companies are the beneficiaries of the massive investments that other industry participants make to complement their product or service. Microsoft and Intel are prime examples. Eighty percent to 90 percent of the PC software applications are designed to work with Microsoft's personal computer operating system (e.g., Windows 98) and with Intel's microprocessor design (e.g., Pentium), the combination often referred to as Wintel. As a customer, if you want access to the majority of the applications, you have to buy a Microsoft Windows operating system; 90 percent do. As an applications software provider, if you want access to 90 percent of the market, you have to write your software to work with Microsoft Windows; most do.

This is a virtuous feedback loop that accelerates, independent of the product around which it is spinning. The same relationship supports the demand for Intel's microprocessors. Microsoft and Intel do not win on the basis of product cost, product differentiation, or a customer solution; they have system lock-in. Apple Computer has long had the reputation of having a better operating system or a better product. Motorola has frequently designed a faster microprocessor. Microsoft and Intel, nonetheless, have long held the lock on the industry.

Not every product or service can be a proprietary standard; there are opportunities only in certain parts of the industry architecture and only at certain times. Microsoft, Intel, and Cisco have a shrewd ability to spot this potential in their respective fields and then relentlessly pursue the attainment, consolidation, and extension of system lock-in. Some of the most spectacular value creation in recent history has resulted. By 1998, Microsoft had created $270 billion of market value in excess of the debt and equity investment in the company, Intel had created $160 billion, and Cisco had created $100 billion.

In a nontechnology area, the Yellow Pages is one of the most widely recognized directories and most strongly held proprietary standards in the United States. The business, which has massive 50 percent net margins, is a fundamentally simple business. The Regional Bell Operating Companies, including Bell Atlantic, Ameritech, Bell South, and so on, owned the business and outsourced many of its activities, such as sales and book production. In 1984, when the Yellow Pages market opened for competition, there were many new entrants, including the companies that had provided the outsourcing services. Experts predicted rapid loss of market share and declining margins. Afterward, the incumbent providers retained 85 percent of the market, and their margins were unchanged. How did this happen?

The Yellow Pages has tremendous system lock-in. Businesses want to place their ads in a book with the most readership, and consumers want to use the book that has the most ads. When new companies entered the market, they could distribute books to every household but could not guarantee usage. Even with the steep 50 percent to 70 percent discounts the new books offered, businesses could not afford to discontinue their ads in the incumbent book with proven usage. Despite enhancements like color maps and coupons, consumers found the new books with fewer and smaller ads to have more size advantage than utility and threw them out. The virtuous circle could not be broken, and the existing books sustained their market position.

Financial services is another industry in which standards have emerged and are a force in determining competitive success. The key players in the credit card system are merchants, cards, consumers, and banks. American Express was the dominant competitor early on, albeit with a charge card rather than a credit card. Its strategy was to serve high-end business people, particularly those traveling abroad. The wellknown slogan, "Don't leave home without it", and a worldwide array of American Express offices helped Amex achieve something close to a customer solutions position. Securing a lot of merchants was not part of Amex's strategy.

In contrast, Visa and MasterCard designed an open system, available to all banks, and aggressively pursued all merchants, in part through lower merchant fees. They created a virtuous loop—consumers prefer the cards accepted by the majority of the merchants, and merchants prefer the card held by the majority of the customers. This strategy culminated in strong system lock-in and MasterCard and Visa's achievement of a proprietary standard. Visa and MasterCard now represent more than 80 percent of the cards in circulation. It is interesting to note that at this time, Microsoft, Intel, and Visa and MasterCard are all under threats of suits by the U.S. Department of Justice. Excessive power can lead to alleged abuses that call the attention of regulatory agencies.

One should not necessarily conclude that the pursuit of one strategic position is always more attractive than the other. There are big winners and losers in every option. Apple failed at owning the dominant operating standard. Banyan failed at achieving a de facto standard in the local area network operating system market, relative to Novell. The right option for a firm depends on its particular circumstances.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 214