Section 2.2. Who s Qualified to Practice Information Architecture?

2.2. Who's Qualified to Practice Information Architecture?Unlike medicine and law, the field of information architecture has no official certification process. There are no university consortia, boards, or exams that can prevent you from practicing information architecture. As we explain in Chapter 13, a number of academic programs are emerging to serve the needs of prospective information architects, but for now very few people have a degree in information architecture. 2.2.1. Disciplinary BackgroundsAs you look over this list, you might not find your home discipline listed. Don't be daunted: any field focused on information and its use is a good source of information architects. And the field is still young enough that just about anyone will have to rely on experience from the School of Hard Knocks to practice IA effectively and confidently. If you're looking for IA talent, keep in mind that, because the field is relatively new and because demand for information architects continues to explode, you can't just post a job description and expect a flock of competent and experienced candidates to show up on your doorstep. Instead, you'll need to actively recruit, outsource, or perhaps become the information architect for your organization. Of course, if you are looking for someone else to fill this role, you might consider the following disciplines as sources for information architects. If you're on your own, it might not be a bad thing to learn a little bit about each of these disciplines yourself. In either case, remember that no single discipline is the obvious source for information architects. Each presents its own strengths and weaknesses. OK, on to the list:

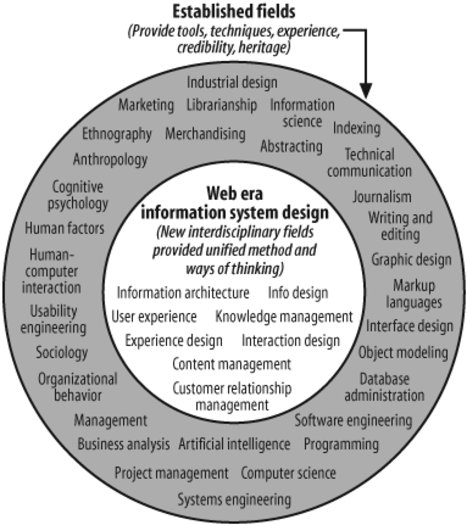

Figure 2-1. Information system design in the Web era (designed with help from Jess McMullin) 2.2.2. Innies and OutiesWhen staffing an information architecture project, it's also worth considering trade-offs between insider and outsider perspectives. On one hand, there's value in having an information architect who can think as an "outsider," take a fresh look at the site, and be sensitive to the needs of users without being weighed down by internal political baggage. On the other hand, an "insider" can really understand the organization's goals, content, and audiences, and will also be around for the long haul, helping to design, implement, and manage the solution. Because it's difficult to choose between these two perspectives, many intelligent organizations put together a balanced team of consultants and employees. The consultants often help with major strategy and design initiatives, and provide highly specialized varieties of IA consulting, while the employees provide continuity as projects transition into programs. Even if you're the lone in-house information architect, you should seek to work with outieswhether by convincing management to hire consultants or specialists for you to collaborate with, or simply by hanging out with and learning from other IAs at local meetups and conferences. Really, the fact that both innies and outies are flourishing is a sign of the field's maturation: in IA's early years (coinciding with this book's first edition), most practitioners were outies, working at agencies and consultancies. After the bubble burst (see the second edition), many of us ran for cover in the security of working in-house, often assisting with the implementation and customization of large applications like CMS and search engines. And now, as our third edition comes out, the field is in balancethere is room for both innies and outies, and a symbiotic relationship exists between them. It's truly indicative of a healthy profession, and good insurance against the vagaries of the next sudden economic downturn. We're not going away. 2.2.3. Gap Fillers and Trench WarriorsIA's early practitioners got their jobs by taking on work that no one else wanted or realized existed. Structuring information? Indexing it? Making it findable? Even if these tasks sounded appealing, few had the vocabulary, much less the skills, to address them. So stone-age information architects were, by definition, natural gap fillers who often tackled these tasks out of opportunism or simply because someone had to. Over the past five or seven years, the field has matured and the practice of IA has solidified. What an information architect does is now much better understood and documented; you'll even detect a whiff of standardization among job descriptions. In effect, IA has moved from the exotic to the everyday, and more and more the people filling those roles are heads-down crack experts in the nuts-and-bolts of IA practices. These are the information architects that you'll want and need down in the trenches, grinding out an information architecture amid the guts and gore of your organization's users, content, and context. These trench warriors aren't pioneers, but providers of an important commodity service. Of course, as trench warriors began to take over, gap fillers didn't disappear. They saw other opportunities that needed fillingonly this time, the gaps popped up in the field of IA itself, rather than within specific teams or organizations. Information architects are now making livings as independent consultants, often working in such specialized areas such as taxonomy development, or as user experience team leaders, or as teachers and trainers for in-house IAs. Increasingly, many of us have become independent entrepreneurs who are developing own IA-infused products and services; there are always new gaps to be filled. As the field continues its healthy evolution, gap fillers and trench warriors will continue to fill changing roles. Whether you're looking to staff your team, hire a consultant, or determine if IA is in your future, it's important to know that the field is now large and healthy enough to accommodate many personality types. 2.2.4. Putting It All TogetherWhether you're looking to become an information architect or hire one, keep this in mind: everyone (including the authors) is biased by their disciplinary perspective. If at all possible, try to ensure that various disciplines are represented on your web site development team to guarantee a balanced architecture. Additionally, no matter what your perspective, the information architect ideally should be responsible solely for the site's architecture, not for its other aspects. It can be overly distracting to have to deal with other, more tangible aspects of the site, such as its graphic identity or programming. In that case, the site's architecture can easily, if unintentionally, get relegated to second-class status because you'll be concentrating, naturally, on the more visible and tangible stuff. However, in the case of smaller organizations, limited resources mean that all or most aspects of the site's developmentdesign, editorial, technical, architecture, and productionare likely to be the responsibility of one person. Our best advice for someone in this position is obvious but still worth considering. First, find a group of friends and colleagues who are willing to be a sounding board for your ideas. Second, practice a sort of controlled schizophrenia in which you make a point to look at your site from different perspectives: first from the architect's, then from the designer's, and so on. And look for company among others who are suffering similar psychoses; consider joining the Information Architecture Institute[

|

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 194

] and attending the annual ASIS&T Information Architecture Summit.

] and attending the annual ASIS&T Information Architecture Summit.