Value Exchanges and Value Creation

|

The idea that value creation should parallel value capture turns us back to the idea of market relationships as value exchanges (Bagozzi, 1975). Within mainstream economics, market is identified as an arena in which one's selfinterest matches the self-interest of others (Adler, 2001). According to Kotler (1972) a marketing exchange is an exchange of "things of value," defined as "not limited to goods, services, and money; they include other resources such as time, energy, and feelings" (p. 48). Bagozzi introduces the idea of a network of relationships by launching the concept of complex marketing exchange, which occurs when there are at least three parties involved in a system of relationships. Each party is included in at least one direct exchange, and the total system is arranged through an interconnecting web of relationships (Bagozzi, 1975).

Marketing researchers agree that customer value refers to the trading off of benefit versus sacrifice experiences within use situations (Flint et al., 2002). But in modeling social relationships in multi-agent systems, Castelfranchi (1998) states that self-interest relates to agents' preferences, and preferences are not necessarily only concerned with tangible benefits: "being rational" says nothing about being altruistic or not, being interested in capital (resources, money) or in art or in affects or in approval and reputation! Although everybody (especially economists and game theorists) will say that this is obvious and well known, in fact there is a systematic ambiguity and bias. By adopting a rational framework, we tacitly import a narrow theory of agent's motivation, i.e., the Economic Rationality which is (normative) rationality + economic motives (profit) and selfishness." On the contrary, rational agents can rationally plan and choose on the basis of unselfish goals.

The idea of exchange in marketing has been expanded by Bagozzi (1975) for including social exchanges. He defines exchange as, "a transfer of something tangible or intangible, actual or symbolic, between two or more social actors" (p. 92). An expanded view of value allows us to begin redefining value to understand knowledge and intangible benefits as currency in its own right. They are benefits that are desirable or useful to their recipients so that they are willing to return a fair price or exchange. We may exchange knowledge directly for knowledge or exchange knowledge for tangible goods, services or money. We could also exchange knowledge for other intangible assets, such as customer loyalty (Allee, 2000).

This symbolic part of consumption has become increasingly important in the post-fordist era (Rullani & Romano, 1998; see also Arendt, 1958; Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). In the era of the Internet the information dimension of the value chain can be separated from the tangible part of it (Shapiro & Varian, 1998) and due to the increased sophistication of the customers (Vicari, 1995; Busacca, 2000), the intangible part of the exchange has often a separate and explicit economic value. We include (see Mandelli, 1998, 2001) these intangible resource flows in value exchanges on which network business models are built. Actors in a network can be interested in buying intangible resources (knowledge and relationships) if:

-

These resources can be exchanged in the market with other agents (for example, the sale of consumers' attention to advertisers in the media industries);

-

These resources can create competitive advantage and can be channeled toward later superior economic return.

These intangible resources can be considered costs in the exchange (relationship investment) when they are required for the transaction, and if they are scarce. We know that knowledge and social capital are not scarce per se, but the resources needed in order to access them are scarce (see the concepts of bounded rationality and bounded sociability in Mandelli, 2004).

Rational actors are believed to search for optimized exchanges. The perfect-market framework takes for granted the idea of fair exchanges between economic actors, because prices are set by the free encounter of demand and supply in an information-transparent setting. In a cooperative framework, fair exchange is guaranteed by trust and social goals (Axelrod, 1984; Adler, 2002). Since both perfect markets and perfect cooperative networks are only ideal-typical models of society (Grandori, 1999), we also need to understand the dynamics of "unfair" value exchanges. We need to conceptualize value exchanges not as fair exchanges, but as rationally bounded, socially embedded, and power constrained "satisficing" (Simon's, 1972) exchanges.

From Value Chains to Cognitive Value Networks

In the past the value creation process in businesses was considered (Porter, 1985) as a linear hierarchical value chain, which described a series of value-adding activities connecting a company's supply side (raw materials, inbound logistics, and production processes) with its demand side (outbound logistics, marketing, and sales). But value chain thinking is rooted in a fordist model of production (Rullani & Vicari, 1999), and has been displaced by the new value constellation or value network framework (Norman & Ramirez, 1993; Christensen & Rosenbloom, 1995; Parolini, 1996; Tapscott, 1996; Allee, 2000; Amit & Zott, 2001).

Value networks are networks of up-stream and down-stream partners, companies and final customers, but also horizontal partners that collaborate in order to create a final added value for each node of the network (Amit & Zott, 2001). Networks are dynamically formed and value is co-produced by different partners in this network-based value creating system (Norman & Ramirez, 1993).

Research concerning the role and importance of inter-firm relations and networks in business is rapidly expanding in different disciplines (H kansson & Snehota 1995; Achrol & Kotler, 1999; Powell et al., 1996; Adler, 2001). A significant contributor to the development of theory and research in this area is the European Industrial Marketing and Purchasing (IMP) group that has conducted many studies on inter-firm relations for developing a theory on business networks (H kansson & Snehota 1995). This approach views business relationships as comprising three layers or effect parameters (H kansson & Snehota, 1995): activity links, resource ties and actor bonds. Activity links refer to the connections among operations that are carried out within and between firms in networks. Resource ties are formed as partners exchange resources in carrying out their activities, in the process often transforming and adapting existing resources and creating new ones. Actor bonds are the social ties between actors, perceptions and attitudes about each other which arise over time and are mutually adapted through the knowledge and experience gained in interaction. These cognitive maps affect the way actors view and interpret situations, as well as their identities in relation to each other and to third parties. Bonds include closeness-distance, degree of commitment, power dependence, degree of cooperation, and conflict and trust among relationship partners.

Both suppliers and customers in a dyadic business relationship are, in turn, connected to other partners that affect the exchange, forming a business network made of a set of two or more connected business relationships. So the actor bonds, activity links and resource ties concerned with a single dyadic relationship are connected to a wider web of actors, activity patterns and resource constellations comprising the business network (H kansson & Snehota, 1995). In the network marketing approach, the value chain is viewed as a network of relationships which create value starting from partners' long-term bonds and their shared cultural frameworks and norms. The exchanges in an interactive network are, according to this approach, driven by values and norms of behavior, rather than by logical and rational planning and are embedded in a "learned" social symbolic reality that is "framed through interpretation and ex-post rationalization of past experience" constructed by a social process of communication through codes, symbols and routines.

The network marketing literature, started in the seventies, does not address specifically the disentangling of the value chain due to the network technologies, but highlights the role of social ties and cultural construction of reality in defining the new competitive territory. This literature describes all businesses as social and cognitive networks, regardless the changes due to the impact of technology. The more recent literature on network management, instead, is particularly concerned with the changes in the way businesses are conducted, due to the disintegration of the traditional vertical value chains into dynamic networks of specialized activities, as a consequence of new communication technologies (Norman & Ramirez, 1993; Parolini, 1996; Evans & Wurster, 2000).

The division of cognitive labor has been the organizational answer to this challenge of complexity that organizations face in the post-fordist economy (Rullani, 1998; Rullani & Vicari, 1999). The infrastructure of this cognitive division of labor is the network, defined as "a system of nodes which use the same language for elaborating their knowledge and which actively govern their reciprocal interdependencies, in order to make them safe and reliable" (Rullani, 1998, p. 51).

Strategic networks are "stable inter-organizational ties which are strategically important to participating firms. They may take the form of strategic alliances, joint ventures, long-term buyer-supplier partnerships, and other ties" (Gulati, Nohria, & Zaheer, 2000, p. 203). Networks provide access to information, markets, and technologies (Gulati et al., 2000), allow partners to share risk, generate economies of scale and scope (Shapiro & Varian, 1998), facilitate learning and innovation (Dyer & Singh, 1998) and improve the efficiency of coordination (Gulati et al., 2000).

In Norman and Ramirez (1993), "strategy is the way a company defines its business and links together the only two resources that matter in today's economy: knowledge and relationships or an organization's competencies and customers." The configuration of the value network viewed from the standpoint of a specific firm is the network business model (Mandelli, 1998, 2001; Amit & Zott, 2001), defined as "the content, structure, and governance of transactions designed so as to create value through the exploitation of business opportunities" (Amit & Zott, 2001, p. 513). This concept draws on network theory and its core idea that unique combinations of inter-firm cooperative arrangements such as strategic alliances and joint ventures can create value (Dyer & Singh, 1998). However, while the strategic alliance perspective considers the network as the competitive unit of analysis, the value network approach "views interfirm cooperative arrangements as necessary elements to the firm's ability to enable profitable transactions. ... each business model is centered on a particular firm" (Amit & Zott, 2001, p. 513).

Building on a previous definition of a business model as the formula concerned with "who pays what to whom" (Mandelli, 1998), we defined (Mandelli, 2001) a business model as the architecture of value exchanges in the value network. With "architecture" we intend the structure of the network and the nature of the exchanges. We agree with Amit and Zott that we can call this an issue of governance describing the way transactions are dynamically organized in the networks of relationships enabled by new ICT. It includes the resource-based perspective because it locates in the network the unique capabilities that create sustainable competitive advantage and it puts at the core of the network its ability to create value for each node. The network creates competitive advantage if each node of the network extracts perceived added value from that specific combination of relationships, compared to participation to other networks. This advantage is sustainable just because it is based on intangible resources, which are not easily replicable.

The value network approach is consistent with both the resource-based view of competitive advantage and the Shumpeterian idea that the source of value comes from the creative destruction of innovation (Amit & Zott, 2001). The network is the locus of innovation and dynamic capabilities, but also the locus of both value creation and appropriation.

To satisfy these requirements our construct needs to build on inter-firm network literature, including final customers into the network considered. It requires taking from transaction cost theory the idea that the nature of transactions defines the governance form. It also requires that the dynamics of trust construct (Castelfranchi & Falcone, 1999) and Adler and Kwon 's work on social capital (2002) are taken into account as well as the idea that intangible cognitive and social resources are both value extracted and costs in social exchanges.

Rullani and Vicari (1999) and Vicari (20001) conceptualized economic networks as cognitive networks and economic interdependencies as the result of a cognitive division of labor. We have considered value networks in digital economy as cognitive value networks (Mandelli, 2001). Each node activates dynamic connections with other nodes, depending on the perceived, that is, socially constructed idea of value extracted through each specific mediation. The added value for each node is conceptualized as a value equation, that is, a net balance between benefits and costs for the node (elementary or second level) due to the added relationship.

We call it the economy of relationship, which is part (along with the economy of content and infomediation) of the economy of mediation (Mandelli, 2004). We use the term mediation because we consider relationships as social constructions of meaning (Peirce, 1955) mediated by language and communication technology (Carey, 1989). Symbolic representations of meaning in communicative acts evolve through the repetitive use of signs, as interdependent actors try to coordinate effective interaction (Peirce, 1955). Each association (mediation) creates contextualized and historically emergent meaning. In our framework, each mediation consumes energy and creates meaning.

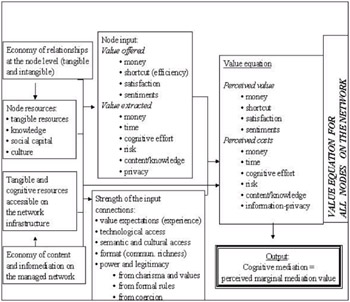

The economy of mediation takes into account both tangible and intangible resource exchanges. Following Vicari's (1991, 2001) approach, all business networks are considered as cognitive networks that are networks of nodes conceived as cognitive maps of the world. We also propose to explicit the value-exchange activation mechanism (Figure 1) at the mediation (dyadic) level, considering not only the flows of resources between nodes, but also the social embeddedness and the power dynamics of these exchanges (Mandelli, 2001). We integrate the value network framework (Normann & Ramirez, 1993; Parolini, 1996; Amit & Zott, 2001), which does not explain the socially constructed cognitive dimension of businesses, with Hakansson and Snehota's (1995) idea on the role of culture in network formation and Rullani and Vicari's (1999) intuition about the networks as webs of cognitive maps.

Figure 1: Node Activation in the Value Network (Source— Mandelli, 2001)

A value network can be seen from the point of view of a single node, and in this case we call it the business model of that node or firm, or at the network level. Our construct also includes the idea that networks have structures and levels. Some nodes of the network are more connected than others to other nodes. There are inter-and info-mediaries, which provide services to the other nodes of the network (Mandelli, 2001). There is a technological and cognitive infrastructure, which supports the network formation and management, but also exchanges value with the nodes.

We start from here to build our concept of cognitive value networks (Mandelli, 2001). We are aware that this conceptualization of value exchanges — as we have described it so far — fits only with the need to explain rational, though socially embedded (and both selfish and unselfish) choices. We need to expand the model in order to include explanations of unplanned behavior and emergent results in complex evolutionary networks.

As cognitive networks these business webs include, besides customers and business partners, also internal cognitive resources. Also, these webs go beyond the vertical relationships between sellers and buyers (Morgan & Hunt, 1994) and include competitors, who are considered both rivals in the economic game and partners in the learning process of innovation.

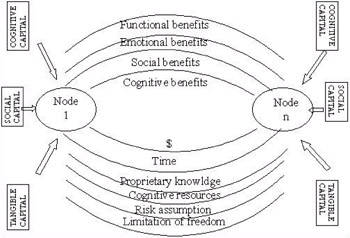

Each node of the value network is considered as both creating and extracting cognitive and social resources in the network (Figure 2), besides exchanging tangible goods against money. Participation to the network, that is, selection and delegation, is based on access, motivation and ability.

Figure 2: Value Exchanged in the Relationship

Motivation to participate resides in both rational and non-rational, selfinterest and unselfish expectations. The addition of a node to the network is driven by the value added by that node, applying to each node of the network the customer value equity concept by Lemon et al. (2001). In this economy of relationships, relational costs are both tangible and intangible. These benefits and costs are different, depending on individual level nodes or organizational (second-level) nodes. Individuals invest — besides tangible resources — time, cognitive effort, risk taking, social capital, proprietary knowledge, and limitation of freedom/privacy. Organizations invest — besides tangible resources — organization effort, social capital, proprietary knowledge and risk taking. Both individuals and organizations capture tangible value, cognitive resources and social resources.

The added value is created through the exchange connections between nodes and the economy of infomediation at the network level, which activates economies of scale, of scope and network externalities (Shapiro & Varian, 1998). The role of network infrastructure is crucial in the economy of any cognitive value network. It creates the economies at the network level and also the platform of common language for cooperation. It also defines the new cognitive and organizational hierarchies, through its structure of infomediation. Ruling the network infrastructure implies also ruling the economy of content and infomediation of the network. That also influences the value extracted at the node level. This is true for all cognitive networks, at the levels of infomediation and of the node.

Cognitive Value Networks and Network Business Models

The conceptual frameworks of value network and of value equation, applied to cognitive and social networks, enable us to explain the motivation to participate and to include a new entrant to a network, without necessarily the condition of fair exchange. These frameworks also help us understand better the drivers of strategic network formation. This provides an answer the question, "When do specific cognitive value networks take the form of strategic networks/inter-firm alliances?"

In our model, networks are not alternative to market relationships and hierarchies. Following the network marketing intuition (Hakansson & Snehota, 1995), all businesses are conceptualized as networks in our framework. Also all relationships, included the ones with the infomediaries, are conceptualized as both delegations referring to cognitive efficiency and hierarchies, and mediations, referring to added value in terms of social construction of meaning and originators of knowledge, social capital or legitimacy. Therefore, we perceive value networks as business conceived as networks of value exchanges and strategic networks as a form of governance characterized by looser ties than organizations and stronger ties than market relationships.

The structure and the dynamicity distinguishes value networks from each other. The pure-market ideal-type relationships, understood as totally symmetric and frictionless, do not exist in reality (see Mandelli, 2004). The difference between real markets and organizations is not based on different degrees of hierarchy, but on flexibility/dynamicity of relationships. Strategic networks are more flexible than organizations and less flexible than market relationships. The strategic managerial decision in this context does not regard only the degree of control, but also the degree of commitment on one side and of risk reduction on the other side. That refers to the social role of organizations and institutions.

In this sense the question, "where does organization come from?" turns us back to theorizing about social contracts. Hobbes' Leviathan state was supposed to be created in order to protect the citizens against the "natural law of nature." For us this refers to the pure-market and his "homo homini lupus" to competition. Social organizations are social contracts, some are short-and some long-term, some are formal and some informal. The state involves the longest-term and most formal social contract. Also organizations, even though reversible, are made of formal social commitment. Strategic business networks, even with long-term ties, are not based on strongly formal commitment, but more on social and informal ties. This makes these forms of organizing more flexible than traditional organizations in times of uncertainty, but also more able to exploit network economies and more protective than market relationships.

This perceived value at the node level explains network formation, even though this does not necessarily imply frictionless decision patterns and social (opposed to self-interest) goals. Social goals that are not motivated by selfinterest are not a specific feature of networks. They are present in networks, along with self-interest and inertial-imitative goals, as well as in markets and organizations.

The satisfaction-trust-commitment link in our model is distributed in all nodes of the network and is conceptualized as perceived value added by the mediation. The stock of the available resources, as in the network marketing approach, embed and contextualize the meaning of the exchanges. Moreover, they create the firm-specific competitive advantage. Competition takes place between nodes and between networks, but the strategic unit of analysis is the focal node. A network is not meaningful, without the cultural and strategic filter of a specific node, namely the variables through which the mediation is evaluated, activated and learned. When a network is conceptualized as a second-level node, it becomes a strategic unit of analysis because it acquires a task, a history and a "soul."

Fair and Unfair Exchanges in a Value Network

At this point we might be tempted to draw a direct link between the interactive structure of new business models and the idea that the exchanges on these networks become more symmetric and, thus, become fair exchanges. This is a logical fallacy. It is true that value capture is the other side of the value creation coin and it is true that value equations must be balanced in order to motivate relationships. However, we argue that this balance is not always a matter of rational calculations and not always a matter of fair exchanges. Let us schematize the motivation schemes behind the decision to establish a network connection.

A node's participation to the network (the activation of the connection between two nodes) within the rational paradigm implies one of the following conditions on which the value exchange must be enforced by or perceived as:

-

one of the two nodes, despite the other node's interest and wish;

-

fair because objectively fair (in the short or long-term);

-

fair by both nodes, even though objectively unfair;

-

unfair by at least one of the nodes, but legitimated by tradition and culture;

-

unfair by at least one of the nodes, but legitimated by charisma and affect;

-

unfair by at least one of the nodes, but legitimated by legal rules.

Out of the rational paradigm, the cognitive exchange could be activated in one of the following other conditions:

-

not because it is considered the best choice, but a relative satisfying choice;

-

not because is considered the best choice, but a step in a trial and error routine;

-

for imitation of other nodes' behavior;

-

random.

Fair exchanges have their conceptual home in both pure markets and cooperative networks. In the first case they emerge from the automatic adjustment of markets made by prices. In the second case they emerge from the social ties of participants (Adler & Kwon, 2002). Pure market hypothesis from transaction cost theory explains the second condition. Hierarchical organization hypothesis from transaction cost theory explains the sixth condition. Social network theory explains the second and third conditions by considering networks as made by cooperative endeavors (Adler & Kwon, 2002); but it also explains the fourth and fifth conditions by considering social networks as embedded in social communities and social ties (Granovetter, 1973; Adler & Kwon, 2002).

The value network framework is consistent with all the conditions of the rational paradigm and the seventh condition, that is, the bounded rationality. It explains both self-interest and altruistic goals of the agents because the resources exchanged can be both tangible and intangible. It also explains the seventh condition because value equation does not evaluate an absolute optimized exchange, but a relative and rationally bounded exchange.

However, the problems exposed by the complexity of our society and its non-rational social exchanges limit the benefits of the idea of a value network. It does not help explain the eighth, ninth and tenth conditions, that refer to the unintentional choices at the node level. Another problem regards the possibility of including these decisions in network-level choices when the processes of creation and appropriation of value happen at the periphery of the system. This means that they are out of the centralized control of managers and emergent from self-organized and difficult-to-predict outcomes. In order to address these issues, we need to go beyond the rationalistic paradigm, and find explanations for emergent and evolutionary network phenomena in theories which explicitly address complex and evolutionary network dynamics.

|

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 143