Self-Organization vs. Hierarchies

|

Management scholars recently have tended to focus on the learning and evolutionary dimension of networks. This is not the only alternative to the rational approach to network formation. Sociological institutionalists (DiMaggio & Powell, 1991) have also adopted the evolutionary approach and stated that whereas economists look at differential efficiency in terms of allocation of resources, they are interested in differential access to resources and legitimacy. Instead of the dichotomy between calculation and trust (self-interest and unselfish exchange), they propose to study the dichotomy between efficiency and legitimacy.

DiMaggio and Powell (1983) cast doubts on rational models of organizational change and introduce a secondary rationality (the search for legitimacy) which does not lead to search for maximization of efficiency as it was in the bureaucratic model, but rather to isomorphism — a constraining process that forces one unit in a population to resemble the other units that face the same set of environmental conditions.

Hierarchical and bureaucratic organization (Weber, 1968) was based on centrality of authority, justified by competence and the search for efficiency (Grandori, 1995). The three causes of bureaucratization in Weber (1968) were:

-

The competition among capitalist firms in the marketplace;

-

Competition among states increasing rulers' need for control;

-

Bourgeois demand for equal protection under the law.

DiMaggio and Powell (1983) claim that the source for organizational change is not competition and the search for rational optimization and efficiency, but for legitimacy, which drives organizational isomorphism, that refers to homogeinity in structure, culture and output (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983, p. 147). The dynamics of change can be interpreted as dynamics of imitation (Garcia-Pont & Nohria, 2002). Organization forms can emerge out of the structuration (Giddens, 1979) of organizational fields (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983). Organizations emerge from cognitive and cultural structures, that is, representations of society. Institutional definition or structuration in this view is made by four steps:

-

An increase in the extent of interaction among organizations in the field;

-

The emergence of sharply defined inter-organizational structures and patterns of coalition;

-

An increase of the information load with which organizations in a field must contend;

-

The development of a mutual awareness among those organizations that they are involved in a common enterprise.

The evolutionary nature of network formation does not exclude a rational-choice attitude of the agents. Axelrod (1984, 1997) shows that co-operation can evolve in a society of self-interested agents without central control through reciprocation strategies. Reciprocation of both cooperation and defection can be the basis of long-term, stable, mutual cooperation. Competitive isomorphism that is driven by rational expectations complements institutional isomorphism that, in turn, is driven by legitimacy expectations (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983). Rational agents complement future-expectation-driven behavior with past-driven behavior. Cooperation becomes the complex and often unpredictable result of these different and intertwined logics.

Also the notion of power helps us address the not-so-optimizing relationships in networks. In their work on social delegation in multi-agent networks, Castelfranchi (1998) and Castelfranchi and Falcone (1998) identify the notions of power and dependence as the key influences on the nature and type of interactions that occur in networks. In a given multi-agent system, there will be many kinds of dependence relations, which build up what Castelfranchi calls a dependence network. It is important to notice that in this framework these dependence relations exist regardless of an agent's awareness of them; they are not understandable only in terms of rational choices. They can emerge either from random behavior or from social and cultural adaptations to changes in the system and the environment.

Social Construction of Reality and the New Media

Browning et al. (1995) suggest considering structures as a pre-condition for cooperation in complex networks. They define structures as the frameworks that emerge in order to bind and give meaning to interactions that include the discussions and speech behaviors needed to build and maintain cooperation (see also Giddens, 1984). In this perspective, structures are emergent, not programmed, cognitive coordination mechanisms; they are the cognitive mediation platform of the network. But these mechanisms build upon social networks. Interactions lead to frameworks that allow new interactions that can create new structures and this interaction sequential process is called reflexivity (Giddens, 1984, cited in Browning et al., 1995, p. 135).

According to Walsh (1995) knowledge structures are "…mental templates consisting of organized knowledge about an information environment that enables interpretation and action in that environment" (p. 286). Framing and priming are the processes through which knowledge structures are formed and construct reality (see Fiske & Taylor, 1991; Entman, 1983). These frames are used as shortcuts for forming new cognitive associations and guiding action. Mandelli (1997) has shown that values and culture influence both cognitive schemata and collective action.

Knowledge structures help understand rationally bounded management decisions in order to create manageable information sets; managers typically utilize top-down information processing and generate cognitive knowledge structures that simplify their information field (Walsh, 1995). These knowledge structures range from heuristics that are designed to create decision-making short-cuts to simplification systems where a large number of information points are coded into a manageable number of categories (Schwenk, 1984). However, knowledge structures are not only in the head of individuals, the internal models by Arthur et al. (1997). They are also externalized in social networks and complex social systems. They help select and interpret reality, that is, to reduce and add variety in the constructionist encounters between physical worlds and human minds and also in the collective construction of reality through the interaction of social agents (Peirce, 1955; Carey, 1989), mediated or not by communication technology.

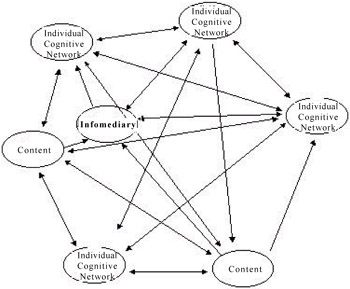

In this view we can redefine cognitive networks as made by cognitive maps, both internal (implicit) and codified (mediated by technology) (see Figure 3). Content and databases are considered codified cognitive maps, and therefore nodes of these cognitive networks.

Figure 3: Cognitive Networks Connect Implicit and Codified Cognitive Maps (Adapted from Mandelli, 2001)

Welch (2002), by reviewing the literature on network theory, reminds us that it is common to think that business networks have shared ideas and shared culture. However, Porac et al. (1989) take a reverse approach, with their focus on competitive groups. They find that the structure of resource exchanges in a value chain affects the information flow and idea structure of firms, while at the same time the prevailing mental models inform the decisions which firms make about resource exchange. The result, they find, is a competitive arena defined by symmetrical mental models throughout the value chain (p. 410). In other words, the mental models of individuals working in a firm align over time and produce cognitive communities which span the boundaries of firms. These cognitive maps can be explicit (formal) or implicit, tacit and embedded in the technology employed and in the behavior and ongoing interactions taking place within the organization and beyond.

In these social, political and cognitive mediations among firms, we find the core of economic value creation in a network. As Welch (2002) states "... such configurations of schemas and ideas emerge in a bottom-up, self-organising way through the micro interactions and schema couplings developing among network actors." But following the mass communication approach to cognitive frames (Entman, 1993), we tend to think that they emerge in interaction with the cognitive managed infrastructures (the media) of the network. Cognitive frames can be explicit or implicit. Cognitive couplings can be direct or mediated by other cognitive frames or by media.

From this perspective social networks built on affect and trust cannot be separated by cognitive networks built on constructionist interpretations of reality. We need to go beyond the separation between information and communication and between knowledge and social meaning. Here, we are not just establishing a simple causal chain between the two, for example, stating that customer satisfaction requires knowledge, and knowledge requires regular interaction, and regular interaction requires trust. We claim that we can build management tools of social complex systems only if we recognize the constructionist nature of their epistemology.

These new concepts help us reinterpret the value-network framework without applying exclusively the rational-choice paradigm. We are not only interested in rational and formal decisions of competition and cooperation, but also in emergent competition and cooperation, which can be partly explained by social dynamics and cognitive structures and infrastructures.

McNamara et al. (2002) showed how cognitive templates, referring to structures as constructive representations of the world, guide action and influence performance. But, as we know from mass communication research, these structures are neither neutral nor "objective" (Carey, 1989; McCombs et al., 1997). They are driven by economic goals and are socially and culturally constructed (Semetko & Mandelli, 1997). Values built out of social networks and public policy arenas are the social filters through which these templates are formed (Mandelli, 1998).

Knowledge structures are socially embedded and this is why we must turn to the study of the formation of social networks and their cultures and their trusttie building for explaining action and emergent social order in cognitive networks

Bonding and Bridging Trust as Governance Mechanisms

Tightness of ties and motivation to cooperation are not anymore fixed concepts in network studies. They are placed in a continuum, with tightness of ties and competition on the opposite end. Also heterarchy, characterized by distributed intelligence and the organization of diversity, has been presented as a new way of organizing. Heterarchies are relationships of interdependence, whereas hierarchies are relationships of dependence and markets are relationships of independence (Stark, 2000). Heterarchy is the firm's response to the increased complexity of its environment (Kauffman, 1990). Stark (2000) claims that for facing uncertainty firms should abandon resource investment in planning activities and distribute the innovation goal to every unit. Because of the greater complexity of these feedback loops, coordination cannot be managed hierarchically. Increased complexity in the environment yields complex interdependencies, and consequently coordination challenges. Where search is no longer departmentalized but generalized and distributed throughout the organization and where design is no longer compartmentalized but deliberated and distributed throughout the production process, the solution is distributed authority (Powell, 1996). Success at simultaneous engineering thus depends on learning by mutual monitoring (Stark, 2000, p. 8). This conception goes beyond the older ideas of firms as made by internal markets, because they consider organizational aggregations (both intra-firm and inter-firm) as dynamic and organizational boundaries as cross-crossed by strategic ties and alliances (Powell, 1990; Kogut et al., 1992). The unit of analysis is the distributed intelligence of networks and their restlessly and redundant options of innovation (Stark, 2000).

According to Stark (2000), organizations' ability of self-redefinition is located in their heterogeneity, namely their redundant and competing options and organizational principles. Heterarchies are complex adaptive systems because they interweave a multiplicity of organizing principles. The new organizational forms are heterarchical because they have flattened hierarchies, and also because they are the sites of competing and coexisting value systems. The organization of diversity is an active and sustained engagement in which there is more than one way to organize, label, interpret, and evaluate the same or similar activity. Rivalry fosters cross-fertilization (Stark, 2000, pp. 9–10).

Stark's view differs from the opinions of scholars who consider markets as social networks. Rivalry of cultures and worldviews is the opposite of the idea of shared culture we think of when we speak about communities (McAlexander et al., 2002). In Stark's (2000) approach, complexity does not transform hierarchies into new cooperative networks, but makes dynamic markets of diverse and competing world views emerge and offers diverse decision options. The interdependencies in these complex and plural networks are based essentially on the necessity of a distributed intelligence, more than on social ties and norms. The locus of innovation is neither the social network nor the recombination of diverse knowledge sets (recombination of organizational routines in Nelson & Winter, 1982), but rather the recombination of diverse systems of evaluations, diverse moralities. This approach suggests that cooperation is not important to make the diverse worldviews speak to each other. What is unimportant is that cooperative agents share the same norms and culture. Bridging diverse communities is more important than bonding local and specialized networks.

Consistently with the sociological studies on bonding and bridging trust between individuals (Putnam, 2000; Norris, 2002), different types of trust are believed to influence organizational performance in business-to-business settings. According to the weak-tie theory (Granovetter, 1973), distant and infrequent relationships are efficient for knowledge sharing because they provide access to novel information by bridging otherwise disconnected groups and individuals. Strong ties, in contrast, are likely to lead to redundant information because they tend to occur among a small group of actors in which everyone knows what the others know.

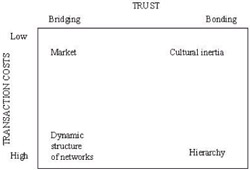

The positive role of bridging trust in innovation can be also relevant for the study of new network forms of organizing (McEvily & Zaheer, 1999; Adler & Kwon, 2002). Uncertainty driven by complexity and the stock of original social and cognitive resources, influence transaction costs in relationships (Mandelli, 2004). Trust diminishes other types of transaction costs (for example, information search costs), and therefore increases variety options when it bridges differences, but it also reduces options when it works as a shortcut in complexity management. The bridging type of trust, that is, weak ties, decreases hierarchies and bonding type of trust increases hierarchies. We believe that the combination of these two types of social capital with the amount of the transaction costs may influence the emergence of different governance forms (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Relationships Between Trust and Transaction Costs

Within-group bonding ties in digital economies may generate social fragmentation and increase transaction costs, but they can also increase the stock of social capital which can be spent for developing new social ties in specific contexts (Mandelli, 2004). The act of delegation is influenced by the trust network (Castelfranchi & Falcone, 1999), the structure of info-mediation and the access to it, and by the trust that the agents have in the infomediaries (see Mandelli, 2004).

If we know the organization goals and the set of available resources, we can support the process and help the governance institution form emerge or loosely design it. We can invest in bonding ties when we need strong group identity and make actors feel more confident in the use of community environments. We can invest in weak ties when we need to foster innovation and bridge diversities, since we know the role weak ties perform in the diffusion and growth of complex networks.

However, weak ties also have drawbacks. Researchers studying product innovation have analysed the difficulties in transferring complex knowledge, particularly tacit knowledge (Zander & Kogut, 1995; Hansen, 1999). For developing weak ties and exploiting their innovation power efficient translators, cognitive standards and structures are necessary. Strong ties are to be coupled with weak ties if we want to foster both cooperation and innovation. Differences should be allowed to emerge, as well as variation but also standards. A good example to explain this is the case of Linux. Axelrod and Cohen (1999) showed how the decentralized creation of variation combined with the centralized maintenance of standards was the key of the success of the Linux open source software project. What is considered the most de-centralized IT project has been well equipped with cognitive hierarchies, referring to selection and coordination by hierarchy.

Decentralization is a pre-condition for innovation and management of complexity, but the network organization builds on knowledge sharing. The pre-condition for the distributed cognition is some form of centralization of the learning process and the distribution of knowledge. We need standards and legitimacy in the selection of knowledge. So cooperation in complex social systems is not a magic formula or "order for free." It requires a set of preconditions and considerable investments. It also builds on a special form of hierarchy: cognitive gatekeeping and institutions.

Information gatekeeping (White, 1950; McCombs et al., 1997; Mandelli, 2001) is the formal process of selecting relevant information for social control on the everyday life of communities. It is based on the idea that social selection is generated by the agenda-building and the agenda-setting processes. These processes are driven by the media system and the cognitive and political negotiations by the policy actors, in culturally contextualized policy arenas (Semetko & Mandelli, 1997). It is not simply a matter of bottom-up selection of variance, but of policy action. Also in networked societies and organizations, we need a legitimated system of agenda-building and agenda-setting if we want diverse and distant worlds to coordinate their knowledge-production and knowledge-distribution efforts. We argue that in complex networked systems we need institutions, but these hierarchies are mainly cognitive. They base their legitimacy on cultural norms or on formal rules (a formal gatekeeping system).

Cognitive hierarchies (the new infomediaries) are not necessarily centralized, by using Kelly's (1994) words they can be "lateral." His ideas about network hierarchies include computer-mediated communication: "In the human management of distributed control, hierarchies of a certain type will proliferate rather than diminish. That goes especially for distributed systems involving human nodes — such as huge global computer networks" (Kelly, 1994, online).

This idea of new cognitive hierarchies in complex networks is found also in the writings of scholars who study economics with a complex system approach. Networks are not automatically non-hierarchical, because elementary entities may be part of more than one higher-level entity and entities at multiple levels of organization may interact. In this view, reciprocal causation operates between different levels of organizations. Arthur et al. (1997) write that, while "action processes at a given level of organization may sometimes be viewed as autonomous, they are nonetheless constrained by action patterns and entity structures at other levels. And they may even give rise to new patterns and entities at both higher and lower levels."

If we consider hierarchy as selection and delegation, and not necessarily as centralized selection and coercive delegation, we cannot avoid studying the new hierarchies in complex adaptive networks. Self-organization is not the opposite of hierarchy. It is a different form of cognitive hierarchy. Hierarchies are not created equal. We can still use Kelly (1994) for grasping this: "Many computer activists preach a new era in the network economy, an era built around computer peer-to-peer networks, a time when rigid patriarchal networks will wither away. They are right and wrong. While authoritarian 'top-down' hierarchies will retreat, no distributed system can survive long without nested hierarchies of lateral 'bottom-up' control."

An economic example of a networked hierarchical structure comes from the loosely-coupled organization, which is made up of a small core staff and a large web of contractors and partners. Tightness of coupling (Orton & Weick, 1990) refers to the degree to which high levels of commitment between the partners and organizational interdependence characterize the relationship between organization units. According to Weick (1982, p. 380; cited here by Staber, 2001), a loosely-coupled network is one where one member affects another:

-

Suddenly (rather than continuously);

-

Occasionally (rather than constantly);

-

Negligibly (rather than significantly);

-

Indirectly (rather than directly); and

-

Eventually (rather than immediately).

Network ties are weak when partners interact infrequently, have a short history of interactions, and lack intimacy with one another (Granovetter, 1975). Loose coupling adds value primarily in fragmented and uncertain environments, increasing options of variation when the source of value is found primarily in innovation and creativity (Arora & Gambardella, 1990; Staber, 2001).

Firms are limited in the numbers and types of knowledge-sourcing arrangements that they can effectively support (Gulati, Nohria & Zaheer, 2000). If entry and exit from tightly coupled arrangements require higher transaction costs and non-recoverable investments (Parkhe, 1993), then firms using tightly coupled arrangements are expected to face greater resource constraints and reduced flexibility. As a result, firms not willing to be locked into a specific technological paradigm tend to choose more loosely coupled sourcing arrangements (Schilling & Steensma, 2002). Steensma and Corley's (2000) results confirm that the extra flexibility allowed by loosely coupled arrangements to be particularly valuable in highly dynamic technological environments, where technology life cycles are relatively short and paradigm shifts are frequent. On the other hand, researchers of knowledge transfer and learning in alliances suggest that knowledge, especially complex or tacit knowledge, is transferred more effectively when the acquirer and provider organizations are highly integrated and interactive (Lane, Salk & Lyles, 2001; Mowery, Oxley & Silverman, 1996).

One relevant example of a loosely-coupled organization is the case of Nike. The athletic shoe business is fraught with uncertainty, due to shifts in fashion and trade regulations and tariffs. The case is described by Brown et al. (2002, pp. 62-63): "Nike developed a loosely coupled supply chain, based largely in Asia, comprising many specialists and logistics providers. These suppliers cover every stage of shoe production, from the sourcing of materials to the assembly of finished shoes and their delivery to retailers. Nike, broadly specifying outcomes for each milestone of the process, manages the interfaces between the suppliers' activities but doesn't attempt to micromanage the activities. ... This approach lets Nike move quickly to meet business challenges. If consumers suddenly decide that they want more rubber in the soles of their shoes, for instance, Nike can quickly revamp production, steering activities toward specialists that are better at sourcing, producing, or cutting a particular kind of rubber for new designs. If tariffs on goods from one country rise, Nike shifts production to suppliers in another."

Management of a loosely-coupled network like this means (Brown et al., 2002):

-

Recruit participants into process network;

-

Structure appropriate incentives for participants; encourage increasing specialization over time;

-

Define standards for communication, coordination;

-

Dynamically create tailored business processes — involving multiple service providers — to meet customer needs;

-

Assume ultimate responsibility for end product;

-

Develop and manage performance feedback loops to facilitate learning;

-

Cultivate deep understanding of processes and practices to improve quality, speed, cost-competitiveness of network.

The role of Nike in this network is "the orchestrator." They mainly build and manage the network. Orchestrators are "learning organizations" with privileged relationships; their employees may never touch a product. Such organizations mobilize other companies' assets and capabilities to deliver value to customers (Brown et al., 2002, pp. 68–69). In short, orchestrators become managers of the cognitive and social assets of the network. Nike does not control the micro-organization of their suppliers. It controls the end-product and builds holistic evaluations through learning relationships with its partners.

Regarding the social impact of these new forms of organizing, it is worth noting that loosely-coupled systems, like the one described, are not flattening hierarchies and redistributing power. The orchestrator is not only the focal firm of the network; it is its leader, and its decision power is much greater than the power located in the periphery (in this case, center and periphery also refer to different parts of the world). As Rullani (1998), Gottardi (1998) and Powell (2001) note, the social externalities of these new forms of organizing can also be negative. Radical flexibility in the process changes the way of organizing the firm and its profitability, but also it may change the quality of life of the people involved in these processes. Also, there may be a social impact of these networks on the logistics of the involved territories (Gottardi, 1998), that we are not ready to grasp and evaluate.

This is not an automatic, "order for free" and frictionless outcome of technological diffusion. It is a matter of social organization and policy choices. The structures of networks evolve and change over time and they can be designed and managed by network leaders (Lorenzoni & Lipparini, 1999; Rullani & Vicari, 1999; Vicari, 2001). But these networks are neither traditional hierarchical institutions. The complex interplay between periphery and center, between local self-organization and central coordination is not a matter of hybrid or intermediate forms of governance, beyond markets and hierarchies. It is a matter of governance of complex evolutionary social systems. Networks, considered as hybrid forms of coordination, cannot explain all the complexity of new organizational forms.

Network communication technology, and the explosion of interconnection brought about by technological changes, has increased the complexity of societies and economies. Complexity of organizations and their environments makes it impossible for managers to predict strategy outcomes (Stacey, 1995). These outcomes are partly emergent from non-programmed phenomena and partly intentionally decided (Minzberg & Waters, 1985).

Complex System Theory and Cognitive Value Networks

Complexity theory in general, and self-organizing systems theory in particular, offer a systematic framework to study the complex non-linear influences, which drive the emergence of communication and business networks (Contractor & Seibold, 1993; Salancik, 1995; Thietart & Forgues, 1995; Brown & Eisenhardt, 1997). Trust and learning play an important role in this evolution (Falcone & Castelfranchi, 2001).

Arthur et al. (1997) describe six features of an economy that presents difficulties for the traditional economics:

-

Dispersed Interaction of Many;

-

No Global Controller of the Interactions;

-

Cross-cutting Hierarchical Organization;

-

Continual Adaptation;

-

Perpetual Novelty;

-

Out-of-Equilibrium Dynamics.

A specific characteristic of these types of systems is that economic agents form expectations, build up models of the economy and act on the basis of predictions generated by these models (Arthur et al., 1997).

We hypothesize that it is possible to manage these types of complex economic systems if we understand the new complex and socially constructed trade-offs (Axelrod & Cohen, 1999) and the new cognitive and social hierarchies, driven by the economy of network and the economy of relationships. Infomediation infrastructures and the stock of historically built cognitive and social resources, available at the network level, affect these trade-offs and the potential system performance.

We build on Vicari's (2001) idea of complex networks as cognitive networks and his call for a deeper understanding of the role of network economics in the explanation of network evolution. We have proposed (Mandelli, 2001) to do it by integrating the value network approach with the information rules (Shapiro and Varian, 1998). We think that the information rules explain the economy of infomediation, but they do not get the picture of the economy of relationships. We need to work on this second dimension, beyond the frictionless perspective (see Mandelli, 2004) and its disregard of power, social dependency and cognitive hierarchies in the social evolution of networks. We need to reintroduce the study of transaction costs in the network value exchanges (Mandelli, 2001). They are different than before because, in complex interconnected systems, value exchanges are ubiquitous, dynamic, and contextualized through access to distributed and collaborative knowledge (Mandelli, 2001), but they still drive organizational trade-offs and create cognitive hierarchies.

We have explained the cognitive value network approach, warning that with that model, until that point, we were able to explain only the rational/ intentional choices at the node level and the system-level effects, due to the economies of networks. We need to include the evolutionary complex system perspective in our framework if we want to understand the principles of management in systems where:

-

The choices are not all intentional;

-

The system-level effects are more than the sum of the node-level effects, and are not all due to the economies of networks.

We need to consider a cognitive value network as an evolutionary and historical process, not as a static state of value exchanges. We call it the Complex Evolutionary Value Network approach. As trust builds trust, knowledge builds knowledge, trust builds knowledge, knowledge builds trust, and cognitive value networks build cognitive value networks.

We add evolution and complexity to the value network approach. Nodes are cognitive systems and networks are systems of systems. The structures of networks are dynamic. Technologies change these systems because they make the ubiquity of connectivity and the complexity of the systems explode. This multiplies both the dynamicity of the system and its not-programmable performance. The new economy is characterized by flexible and parallel interconnectivity, not just by the number of connections. The ubiquitous technology dynamically connects node-level cognitive maps with the collective intelligence of the network. This also increases the potential richness of the encounters, because it fosters the integration between different channels of connections.

We want to understand what are the trade-offs, the different outcomes of different solutions, in a mediation process. The question is again: "What does create value in a mediation?" We try to answer this question, building on what we have understood so far, studying the economy of relationships. The drivers of value in a cognitive mediation are:

-

Access to variety (lack of cognitive hierarchies, looking for optimization of the result of the mediation);

-

Bridging diversity (lack of social hierarchies, looking for innovation and creativity);

-

Efficiency in the access and selection phases (optimization of the mediation process and the consumption of time and cognitive resources);

-

Legitimacy in the selection process (legitimated gatekeeping and lower risk).

In the evolutionary perspective, the different nodes are seen as dynamically (because encounters are flexible) and historically (because cognitive maps are evolutionarily learned) part of different networks.

Network efficiency at the node level requires a collaborative access to relevant knowledge sources, considered as a collective intelligence of the network, without which the ubiquitous dynamicity of the encounters is not possible. Legitimacy works as a trade-off with efficiency (as in DiMaggio & Powell, 1983) when it substitutes variety and asks for abandoning the search for optimization. But it also drives efficiency, when it works as delegation, shortcut and heuristics. Legitimacy does not come out only from formal rules and institutions, but also from social capital and bonding ties.

All these variables are affected by the stock of cognitive and social resources available at the node level and by the structure and the economies of infomediation at the network level. The locus of management of complex cognitive value networks is the infomediation infrastructure, its diversity, its efficiency and its legitimated selection of variation. This managed infrastructure "loosely couples" creative and self-organized local networks. It is not a static and formal institution; it accumulates evolutionary collective knowledge and mutually adapts to the changes in the network. The network is only loosely managed, but the mediation infrastructure is strongly managed.

|

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 143