Management in Complex Evolutionary Networks

|

Trust is an evolutionary phenomenon, which drives social delegation, constrained by the economics of mediation, both at the node and at the system level. Trust and cooperation are also emergent from non-rational path-dependent and "unthinking" relationships (Macy, 1998). Also in Arthur et al. (1997) there is explicit mention to these "emergent" economic choices in complex adaptive economies.

This idea is completely different from how we are used to thinking about rational choices in linear economics. This is how Macy (1998) puts it: "This game-theoretic analysis assumes strategic foresight based on complete information and a perfect grasp of the logical structure of a well-defined problem. ... However, in everyday life, most games are played by lay contestants, not mathematicians." These games are often highly routinized, played according to internalized rules or instructions, with little conscious deliberation. The players rarely calculate the strategic consequences of alternative courses of action but simply "look ahead by holding a mirror to the past" (Macy, 1998).

But complex worlds are not made by all complex realities. There are occasions in which it is more efficient to think in terms of causal relationships, as models of reality (Castelfranchi, 1998; Arthur, 2000). Arthur (2000) suggests thinking at human cognition in economics, as a process of association searching. Sometimes this process is guided by more information and explicit logical steps of framework associations. Sometimes it is guided by loosely-tied frameworks. But it is always filtered through one' s experience and history.

This is consistent with the idea (Castelfranchi, 2000) that distributed cooperation (self-organization) can emerge from both rational and "unthinking" choices and rational choices can be both motivated by utilitarian and nonmaterialistic goals. Once we have made clear that all these different events can happen at the individual self-organized level of social exchange, we can address the system level choice problem, that is we can ask the question about how top-down organizational choices can integrate with bottom-up choices (Castelfranchi, 2000). As Agre (2001) reminds us, even "the most intellectually serious proponents of self-organization," such as Hayek (1948), recognize that, "the libertarian economy requires a robust institutional framework before the miracles of self-organized complexity can reliably occur" (p. 15).

Also the system, not only the individual agent, can have rational and "unthinking" dynamics.

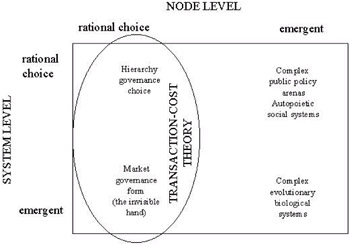

What can be very rational and functionally evaluated at the individual level can become the "unthinking" emergent behavior at the system level, if the pure-market form of system governance is considered. The "invisible hand" of the market is rationally driven self-organization. Transaction cost economics doesn't go beyond this point in exploring emergent behaviors. The public policy school in neo-institutionalism and complex system theory applied to social science try to understand also the other quadrants of the matrix (Figure 5).

Figure 5: System and Node Level Choices

We have four levels of governance problems here:

-

The policy level: What is it possible to plan in a complex evolutionary network?

-

The self-organization, self-utilitarian choice level: How do the individual rational decisions create an upper level social order?

-

The self-organization, non-utilitarian choice level (the same as the one before);

-

The self-organization "unthinking" choice level: How the path-dependent and non-rational dimension of choice serves rational upper level goals?

For going further we need to dig deeper in the understanding of how value exchanges can emerge and structure complex evolutionary systems.

Cognitive Value Networks as Complex Evolutionary Systems

We tend to agree with Axelrod and Cohen (1999): complex systems cannot be completely understood and predicted but they can be harnessed. They can be managed (Vicari, 2001). "In complex adaptive systems there are often many participants, perhaps even many kinds of participants. They interact in intricate ways that continually reshape their collective future. ... We see variation, interaction, and selection as interlocking sets of concepts that can generate productive actions in a world that cannot be fully understood. ... While complex systems may be hard to predict, they may also have a good deal of structure and permit improvement by thoughtful intervention" (Axelrod & Cohen, 1999).

In this perspective "harnessing complexity," means "channeling the complexity of a social system into a desirable change." This is why the fundamental questions become (Axelrod & Cohen, 1999, p. 23):

-

What is the right balance between variety and uniformity?

-

What should interact with what, and when?

-

Which agents and strategies should be copied and which should be destroyed?

Also Axelrod and Cohen (1999) pay attention to the economics of selection and mediation. According to them a relevant difference between complex biological systems and complex social systems is the cost of variation, interaction and selection.

If the management of complex systems requires the understanding of how the economics of self-organization can integrate with the economics of policy decisions, we can say that the problem becomes how the organization of the network can couple with the self-organized utility decisions at the node or the sub-system level? There must be a way for testing and adjusting the fit of the structure and the set of connections of the system to the system goal. We argue that this management tool is the evolutionary infomediation and learning infrastructure of the network, with its economies.

Complex evolutionary cognitive networks become Complex Evolutionary Value Networks (CEVN) if we find a way of understanding how value is exchanged on these networks and how it is possible to manage them. Our claim (see also Mandelli, 2001) is that centralized management of complex cognitive networks regards the infomediation structures: access, critical resources, legitimation and standards of the mediation platforms. It also regards these structures' economies. Also, we claim that value exchange in complex evolutionary networks can be understood as value created at the network level and extracted at both the individual and the network level. Finally, we claim that it is possible to build systems of control of the value created, if we accept the conceptual basis of the theory of complex evolutionary systems, that is the idea that we can understand history, but we cannot predict our future. In a connected economy our possibility to understand history is potentiated, whilst our ability of predicting the future is marginal. Management systems must leverage this new interpretative potentiality, renouncing to build rigid planning mechanisms. If rationally-bounded management is made by heuristics and trial and error (Simon, 1972), rationally bounded systems of value control must build on richer knowledge, ex-post control, and the ability to change as fast as the environment and system structure change.

We claim that in these networks the nodes are cognitive structures but also social structures. Nodes and sub-systems stock cognitive but also social resources. Also the economics of these social resources, and their bounded sociability, influence the history (and the future) of social networks and their structures and hierarchies. These structures and hierarchies are emergent, not programmed, but also negotiated through explicit and implicit power relationships. If we believe that it is ethically relevant and practically useful to find a non-fundamentalist answer to the challenges of post-fordism (Rullani & Romano, 1998), we should experiment this way of looking at complex evolutionary social systems.

Management, in this context, has the goal of improving the efficiency and the efficacy of the cognitive and social mediations in the system. Management becomes a matter of public policy in complex policy arenas, with managers defining the boundaries, the initial structure and the general rules of the policy arenas.

The infomediation and learning infrastructure provides both cognitive efficiency and learning services to the local sub-systems and individual nodes. The managers of the complex systems have a policy role in the evolutionary learning process, because they set the rules of the game for the cognitive infrastructures. Each complex system is a cognitive value network, because each complex system is a communication network and each cognitive mediation makes the pair of involved nodes invest and extract value from the mediation itself. If the node is an individual cognitive system, the extracted value is made by the benefits perceived in the relationships while the costs are the perceived costs of the relationships. If the node is a sub-system, the benefits are the value extracted at the institutional level by that system and the costs are the resources invested by it. Managers can influence the outcome of the local cognitive exchanges investing in the resources of local actors, but can also influence providing cognitive services through the infomediation and learning infrastructure (Mandelli, 2001).

Reasoning in terms of value network allows us to understand the different cognitive and political role of different nodes in the networks. A value network is always a managed network (Vicari, 2001), that is, a value network always has a manager (an orchestrator) who assigns a goal to the system, not because the mediations and delegations in the system are planned, but because the system builds on a managed cognitive infrastructure, which is part of the original business model designed by the network manager. The orchestrator can be collective and also can be very limited in the decisions he can make, but it is necessary for designing the channel platform, the learning mechanism and the economics of the communication network.

The business model is the cognitive and economic structure of the system, which includes not only the decisions about the original components of the physical network but also the decisions about the resources that can be made available through this infrastructure for the local value exchanges on these networks. It is the idea of the "constraining infrastructures" in Castelfranchi (2000), but with their economic implications.

We are used to saying that the business model of a project on the Internet is the architecture of "who pays whom with what." This helps highlight the idea that the new supply chain is made by local design and not by the external structure of the industry and that resources invested in the social exchanges are both tangible and intangible. Of course the manager of the value network doesn't decide the content of the local exchanges, not even the evolutionary structure of the system. He decides the original structure and manages the system level outcome of the local exchanges, providing the periphery with the learning mechanisms needed for adjusting the fit of the sub-systems. He can also invest in the creation of cognitive and social resources at the local level: cognitive sophistication and different forms of social capital. Cognitive infrastructures and business models are both planned and emergent.

Axelrod and Cohen (1999) write that three key concepts lead to questions that can help identify productive courses of action in Complex Adaptive Systems. The concepts and the questions they generate are:

-

Variation: What is the right balance between variety and uniformity?

-

Interaction: What should interact with what, and when?

-

Selection: What agents or strategies should be copied or weeded out?

We suggest a managerial framework that can help business leaders answer these questions in their contextualized and adaptive organizations: the frame-work of the value networks. But, building on the work of Vicari (2001) and our contribution to that project (Mandelli, 2001), we propose to go beyond the application of this concept to the restructuring of the value chains in network economies. We should consider all the cognitive networks relevant for an organizational strategy as cognitive value networks. But we also propose to consider them as evolutionary complex systems.

We propose to consider an organization as a complex evolutionary social system and to consider its cognitive structure — its hierarchy — as made by its system of mediation and delegation, whose economy becomes the real object of management decisions and performance. The cognitive value networks are made by elementary and complex agents, by psychological and organizational cognitive structures, by the integration of planned and emergent decisions.

The real challenge is to find the way to integrate the system level of management with the self-organized structures. "Typically, (intelligent) agents are assumed to pursue their own, individual goals… The existence of a collection of agents thus depends on a dynamic network of (in most cases, bilateral) individual commitments. Global behavior (macro level) emerges from individual activities/interactions (micro level)" (Castelfranchi, 2000, p. 3).

But in business environments the behavior of the global system, the macro level, is important as well. "Typical requirements concern system stability over time, a minimum level of predictability, an adequate relationship to (human-based) social systems, and a clear commitment to aims, strategies, tasks, and processes of enterprises. Introducing agents into business information systems thus requires resolving this conflict of bottom-up and top-down oriented perspectives" (Castelfranchi, 2000, p. 3).

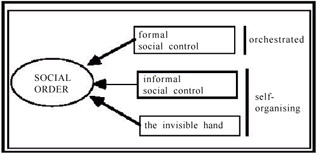

We agree with Castelfranchi (2000) that it is not possible to really design societies and the Social Order. He writes that it is possible to do it only in certain kinds of organizations. In the other cases it is necessary to design only indirectly in designing frameworks, constraints and conditions in which the society can spontaneously self-organize and realise the desirable global effects. (See Figure 6.) We agree and this is why our idea of management tries to get the most from the integration of some forms of planned decisions and the self-organized outcome of the local and autonomous agents.

Figure 6: Social Order (Castelfranchi, 2000)

The managers are both external and internal to the cognitive network. When they set the general task of the system they are environment. But their cognitive maps are internal. They set the original general task of the system. They build and design the original techno-mediation structure: the physical connections. They design and invest in the set of cognitive and social resources of the network. They build the standards and legitimacy mechanisms for bridging the different local variations and increase the innovative power of the organization, making the distributed systems adaptively fit to the upper-level task. They also design and maintain the learning system of this distributed collective intelligence.

Trust is not a given anymore, and it is not only emergent from local ecologies. If it is also a matter of resources and legitimacy, it's also an issue of design and management. Management is not a matter of planning activities anymore; it is an issue of legitimated infomediation and learning systems.

Media as Complex Evolutionary Institutions

The design of the cognitive value networks of complex evolutionary systems is the new strategic task of managers. It requires:

-

Setting the goal of the value network;

-

Understanding the culture and the self-organizing dynamics of the local sub-systems and cognitive exchanges;

-

Deciding the original structure of the network and the rules for joining it;

-

Designing the communication channel platform;

-

Designing the gatekeeping and learning system.

Managers do not design activities. They design goals and communication/ learning systems, so the network can build on better resources and efficiently self-adapt the fit to the assigned goal.

We can design cognitive value networks at all levels of business. We create cognitive value networks when we organize intra-firm relationships or when we develop market alliances or relationships with customers. The dialectics of selforganization and hierarchy in the evolutionary complex systems is fostered by the value added to the local exchanges by the managed cognitive value network. These encounters, sometimes rational and sometimes inertial or imitative, though embedded in local social and cultural settings, are more or less constrained by:

-

External boundaries of physical communication platforms;

-

External boundaries of the cognitive gatekeeping system;

-

Available resources.

Management in this complex system means investing in communication platforms and access to cognitive resources, within the strategic constrain of the economic and organizational goal of the system.

The major difference between the traditional idea of economic institutions and the one we present here, is not particularly concerned with the different degree of the hierarchy of the two. We accept the idea that the new forms of governance in the network economy are networks. We reject the equation between networks and the elimination of hierarchies. Networks are more dynamic than traditional institutions, not necessarily less hierarchical. Networks might be more based on legitimated delegation (hierarchies) than traditional institutions, but not necessarily less hierarchical.

What is most important to understand is how complex and evolutionary institutions emerge from the dialectics of self-organized and centralized decisions and relationships, thanks to the collective learning processes of these cognitive networks to their cognitive gatekeeping systems, but also within the constraints of the economics of network mediation.

We can study the creation and management of the new transaction costs in complex digital networks, through the understanding of the economics of information network management and the economics of dynamic ubiquitous relationships (the dynamic transaction costs) of the multi-channel and immersive digital networks. But we also need to understand the evolutionary economics of trust dynamics and delegation at the node level.

Dynamic value equation evaluations and the consequent delegation actions at the local node level create path-dependent and self-organized sub-systems of trust (trust networks, see Castelfranchi & Falcone, 1999), interconnected to other layers of delegation — horizontal or upper-level — through dynamic structures of infomediation. The very different fabric of this social and economic network systems comes from their extremely complex interconnectedness. It also comes from the continuous flows of knowledge and trust, which creates the need for contextual and dynamic delegation: these are the new hierarchies in the digital markets.

Implications for Management of Cognitive Complexity: The Case of Collaborative Branding

The role of the relationship manager in the Internet economy is to design the cognitive infrastructure for the relevant value exchanges in the value network, and design the business models that allow all strategic nodes extract value from those relationships. Marketing managers do not create communities because communities are complex social phenomena — they cannot be designed. They build a value-exchange platform with the existent communities providing services for the community relationships and helping structure the delegation process. The difference between this approach and the model proposed by the supporters of the community business models in a digital economy is that there is not only one form of relationship in the network economy (the community-based bonding cooperation), not only one form of infomediation (the affiliation type) and there is not only one form of trust-based business model (the community-based business model). Applied to marketing, this means that the adaptive design of the value and trust networks, which link the company to its clients and partners (and their plural delegation dynamics) is not a one-size-fits-all predefined formula; it is just the core of the Internet Marketing strategy.

Brand building and marketing must transform in the management of complex evolutionary value networks (Mandelli, 2001). The task of the system is long-term value extraction for the brand company and a branded relationship is the pre-condition for sustaining competitive advantage in a world ruled by differences created by intangible resources.

Brand building is not a matter of simple targeting anymore. It is neither simply a matter of disintermediation. It's a matter of dynamic integration between planned and self-organized value exchanges, because brand managers can integrate push communication (targeted top-down communication) with pull communication (bottom-up permission marketing services). The brand managers design the temptative (trial and error) cognitive architectures of the original networks. They also can design the infrastructures for collaboration with customers and supply-chain partners, even though they know that the pattern of navigation will be pulled by the customers on the interactive networks.

They can adapt and influence the dynamics of self-organized navigation, building dynamic encounters through the ubiquity of the multi-channel and multi-touch-point strategies. They will win out the so-called "just-one-click-away-competitor" offering richer dynamic services, thanks to the network knowledge management and the customer relationships allowed by the media infrastructure they manage. On the web, brands build new hierarchies because they can offer more efficient shortcuts and offer the value of their mediation. But these hierachies, and their legitimacy, are objects of policy decisions and negotiations, they are not automatic.

Of course we have to acknowledge that value exchanges on these value networks are not always planned, are not always rational. We, the managers, evolve and adapt along with the system we manage. We learn as well as the value system and the value sub-systems learn. The system can learn better and adapt better and perform better if we invest in a better and more dynamic infrastructure for learning and cooperation.

If we conceive brands this way, we can try to exploit both the efficiency of hierarchies and the legitimacy of self-organized mediation. If we conceive brands this way, we can define them as new forms of cognitive governance, as new cognitive institutions. Brand value networks are not the only complex evolutionary value networks we can design and manage. All the relevant business relationships can be conceived as complex evolutionary value networks. They all become new institutions when they become objects of management decisions.

|

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 143

- Assessing Business-IT Alignment Maturity

- Measuring and Managing E-Business Initiatives Through the Balanced Scorecard

- A View on Knowledge Management: Utilizing a Balanced Scorecard Methodology for Analyzing Knowledge Metrics

- Governing Information Technology Through COBIT

- The Evolution of IT Governance at NB Power