Theoretical Lens

|

| < Day Day Up > |

|

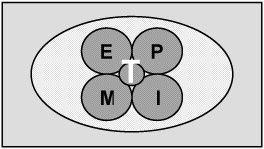

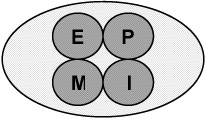

As at heoretical lens, the authors adapted and extended theoretical models from Clark et al. (1997), Paper (1998a, 1999), and Paper and Dickinson (1997). From work began by Paper and Dickinson (1997), Paper (1998b) offers a three-component model of process management and change-readiness featuring people, methodology, and environment. Paper and Dickinson (1997) extended the model to include IT capabilities. Paper, Rodger, and Pendharkar (2001) further extended the model to include vision that weaves the other components together with a "top-down" imperative. Of course, actively involved top management must facilitate the imperative to enhance the potential for effective deployment and implementation. Each of these studies drew conclusions based on in-depth case study research with Caterpillar and Honeywell. Ancillary data was obtained, analyzed, and synthesized from case study work with FannieMae (Paper, 2001), Safeco (Paper, 1999), Bank of America (Paper, 1998b), The Utah Department of Transportation, The Depart-ment of Defense (Rodger & Pendharkar, 2000), The U. S. Military (Rodger & Pendharkar), AntHill.Com (Mills, Paper, & Rodger, 2001), and Vicro Communications (pseudonym). Clark et al. (1997) offers a five-component star model featuring people skills, structure, reward systems, processes, and change-ready IT capabilities. The components "structure" and "reward systems" fall into the "environment" category developed by Paper(1998a). The component "strategy" falls into the "vision" category developed by Paper (2001). Since the component "process" is what organizations are attempting to change to improve performance (Broadbent et al., 1999; Davenport & Stoddard, 1994; Harkness et al., 1996; Kettinger et al., 1997; Nissen, 1998; Paper, 1999), we felt that it should not be a part of our theoretical lens. Figure 1 depicts the theoreticallens we synthesized from key BPR literature. It consists of five interdependent components-environment (E), people (P), methodology (M), information technology (IT) perspective (I), and transformation vision (T).

Figure 1: Theoretical lens

Environment

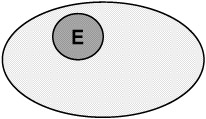

Basic environmental factors (Figure 2) that lead to structural change include top management support, risk disposition, organizational learning, compensation and reward systems, information sharing, and resources (Amabile, 1997; Clark et al., 1997; Lynn, 1998; O'Toole, 1999). Innovation can come from any level of an organization, but environmental change originates at the top (Cooper & Markus, 1995; Paper, 1999). When employees actually see top managers initiating process improvement changes, they perceive that their work is noticed and that it is important to the organization (Paper, 1999; Paper & Dickinson, 1997).

Figure 2: Environment

They may also perceive that their job is in jeopardy or that potential failure will be noticed more easily and criticized (Caron, Jarvenpaa, & Stoddard, 1994). Hence, the fear of failure must be limited and risk taking promoted for innovation to thrive (Nissen, 1998; Paper & Dickinson, 1997). Many organizations make the mistake of trying to manage uncertainty with creative projects by establishing social control; however, it is the freedom to act that provokes the desire to act (Sternberg, O'Hara, & Lubart, 1997).

Freedom without knowledge can lead to disaster. Organizational learning thereby should be cultivated by investing in training and education (Paper, 2001). Training is the key to transformation since people do the work (Paper, 2001). The ability to learn as an organization dictates whether and how fast it will improve (Harkness et al., 1996). Teamwork is another key issue. BPR teams can gain multidisciplinary knowledge and experience from each other due to the functional boundaries crossed when transforming processes (Kettinger et al., 1997). Knowledge exchange between and among teams appears to give some organizations a distinctive competitive advantage (Lynn, 1998). Learning as part of the environment enables top management to disseminate its change message to the people who do the work (Gupta, Nemati, & Harvey, 1999). It also enables people to better understand the business and "their part" in realizing organizational objectives (Paper, 2001; Paper & Dickinson, 1997).

Reward systems are another means to motivate people to change. Compensation has been attributed as a means of motivating employees to perform better (Pfeffer, 1998). Being rewarded for one's work sends the message to employees that their contributions to the organization are valued (Paper & Dickinson, 1997). It seems logical to conclude that people who are well compensated for risk taking, innovation, and creativity will continue that behavior (Paper, Rodger, & Pendharkar, 2000).

Information sharing enables people to better understand the business and what is required to be successful (Harkness et al., 1996; Paper & Dickinson, 1997). Restricting information, on the other hand, inhibits change. Resources can be viewed as a source for providing a variety of services to an organization's customers (Kangas, 1999). According to Barney (1991), an organization's resources can include all assets, capabilities, organizational processes, attributes, information, and knowledge that enable the organization to develop and implement strategies that improve its efficiency and effectiveness.

The environment encapsulates many factors. It is the domain in which people do their work, vision is created and deployed, objectives are carried out, and processes are transformed (Cross, Earl, & Sampler, 1997). Organizations should therefore strive to make their transformation environment more adaptive, dynamic, flexible, and organic on an ongoing basis (Cross et al., 1997; Paper, 1999; Paper & Dickinson, 1997). Further people should be rewarded for creative thinking, initiative, and taking risks (Paper & Dickinson, 1997).

People

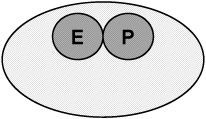

Transformation success hinges on people (Figure 3) and their knowledge, creativity, and openness to change (Cooper & Markus, 1995). Transformation however requires changes in the manner in which people work. A shift in their skills will thereby be required (Cross et al., 1997). Mechanisms to build new skills include training and education, challenging work, teamwork, and empowerment.

Figure 3: Environment and people

According to Wong (1998), education and training are the single most powerful tool in cultural transformation. It raises people's awareness and understanding of the business and customer (Paper, 1998a; Wong, 1998). Training helps develop creativity, problem solving, and decision-making skills in people previously isolated from critical roles in projects that potentially impact the entire enterprise. Business education is equally important in that people need to know how the business works in order to add value to business processes (Paper, 1999; Paper & Dickinson, 1997).

When work is challenging, people are more motivated, satisfied, and often more productive (Hackman, Oldham, Janson, & Purdy, 1975). Challenge allows people to see the significance of and exercise responsibility for an entire piece of work (Cummings & Oldham, 1997). Challenge stimulates creativity in people and gives them a sense of accomplishment (Amabile, 1997).

People cannot reach their creative potential unless they are given the freedom to do so (Pfeffer, 1998). Management, therefore, needs to be sensitive to and a ware of their role in creating a workplace that allows people freedom to act on their ideas. Management must also temper freedom with adherence to objectives and company policy (Paper & Dickinson, 1997). Freedom without some semblance of control may lead to chaos and poor performance. Ownership of work appears to positively impact performance and give people a sense of commitment (Davenport & Stoddard, 1994; Paper, 1998b; Paper & Dickinson, 1997). Management should thereby foster commitment and ownership at all levels (Caron et al., 1994). Finally, management should be tolerant of failure. A willingness to allow failure and learn from it is paramount to BPR success (Caron et al., 1994).

Methodology

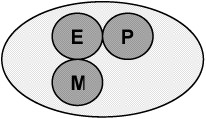

The literature suggests that methodology is the key to effectively dealing with the scope and complexities involved in transformation (Davenport & Short, 1990; Gula, Kettinger, & Teng, 1993; Kettinger et al., 1997; Kim, 1996; Paper, 1998a; Paper & Dickinson, 1997; Talwar, 1993; Teng, Jeong, & Grover, 1998). Transformation cannot be accomplished in the absence of fundamental guiding principles (Hammer & Champy, 1993). Methodology (Figure 4) keeps people focused on the proper tasks and activities required at a specific step of a transformation project. It acts as a rallying point for cross-functional teams, facilitators, and managers as it informs them about where the project is and where it is going (Paper & Dickinson, 1997). It allows people to challenge existing assumptions, recognize resistance to change, and establish project buy-in (Kettinger et al., 1997). Of critical importance in the beginning stages is the buy-in and direction from top management, which is essential to identifying information technology opportunities, informing stakeholders, setting performance goals, and identifying BPR opportunities. Direction is important because large-scale reengineering spans functional boundaries in which people from across the organization are involved (Paper, 1998a). Standard BPR practice recommends development of a process model (Davenport, 1993; Harrington, 1991; Paper & Dickinson, 1997). A process model provides a graphical representation of the targeted processes and a starting point for measurement-driven inference (Nissen, 1998). However, a process model maps out only tasks and activity requirements. It fails to provide high-level support and direction. Methodology, however, provides not only a "step-by-step" map of activities and tasks, but also resources, high-level support, and direction (Paper & Dickinson, 1997). A process model is similar to a 'blueprint' used by engineers and architects. Methodology encompasses the process model but it also embraces the "business vision" of transformation from the managerial point of view.

Figure 4: Environment, people, and methodology

Business and contingency planning for process transformation can be greatly facilitated by developing a customized BPR methodology (Kettinger et al., 1997). Methodology incorporates both top-down vision and bottom-up design. That is, vision originates at the top but design of detailed process activities can only be done by those who do the work (Davenport & Stoddard, 1994). Methodology is therefore a joint activity between top management, middle management, and process workers on an ongoing basis to hone and fine-tune the approach (Paper & Dickinson, 1997).

El Sawy and Bowles (1997) extend the idea of IT-enabled BPR methodology to include the customer support process. The authors argue that customer support should be a key ingredient in process redesign efforts. Instead of focusing only on changing the structure of workflow and the information around it, the authors argue that BPR methodologies must move to a higher order of analysis to formalize the way that the process learns in the redesign process. Given the cross-functional and radical nature of process redesign, a lot is learned by process workers (Paper & Dickinson, 1997). Further, new knowledge is created by those involved (El Sawy & Bowles, 1997). However, the organization can lose this knowledge through attrition if an effort is not made to capture the knowledge on an organizational basis.

IT Perspective

The perspective of IT (Figure 5) professionals toward change is critical because technology implementation is an organizational intervention (Markus & Benjamin, 1996). IT perspective is critical because the role of enabling technologies has been deemed integral to the successful implementation of business process redesign (Broadbent et al., 1999). Technology becomes an even more important factor as the complexity and scope of the project increases (Broadbent et al., 1999). IT professionals can make immediate and important contributions to reengineering projects. Their knowledge of technology project management, solicitation of end-user requirements, structured analysis and design, and rapid application development can contribute greatly to assessing project costs, risks, and benefits (Kettinger et al., 1997). As such, IT can either strengthen or weaken an organization's competitiveness (Kettinger et al., 1997).

Figure 5: Environment, people, methodology, and IT perspective

As introduced by Markus and Benjamin (1996), the three fundamental models of IT change agentry are traditional, facilitator, and advocate. Each model offers the dominant belief system or perspective of IT professionals toward the goals and means of work that shape what they do and how they do it. IT professionals with the traditional perspective believe that technology causes change. IT professionals with the facilitator perspective believe that people create change. IT professionals with the advocate perspective also believe that people create change. However, they believe that the advocate and the team are responsible for change and performance improvements.

Consistent with change-agent theory, IT perspective is categorized rather than measured. IT perspective cannot really be measured because one has one belief system or another (Markus & Benjamin, 1996). The facilitator perspective views change as influenced by the people who do the work. Managers facilitate and guide the process. However, they do not control the process in any way. People control the processes, set their own goals, and are responsible for the consequences. However, managers share goal-setting tasks with the group, champion the effort, and are jointly responsible for the consequences.

Findings by Mata, Fuerst, and Barney (1995) reinforce the facilitator model and suggest that two factors effectively contribute to an organization's competitive advantage: 1) developing methods for strategy generation involving information resources management that emphasize and enforce the learning of these skills across the entire organization, and 2) developing shared goals within the entire organization. This facilitator attitude toward common business processes and systems has been adopted by many organizations, including General Motors (Schneberger & Krajewski, 1999).

An inherent attribute of facilitation is the ability to foster innovation. Innovation involves fostering creativity in people. When changes in IT are involved, usually in conjunction with changes in business processes, creativity is needed (Couger, 1996; Glass, 1995). Creativity, however, can be stifled quite easily in "command and control" environments. Hence, IT staff needs autonomy as well as opportunity for professional growth within a project (Cooper, 2000). An increase in creativity tends to increase the likelihood of alternative IT solutions, thereby enhancing the chances for project success (Cooper, 2000). Success is also dependent upon the buy-in of both business and IT personnel into not only the transformation goals, but also the uncertainties associated with an unproven design (Clark et al., 1997).

El Sawy and Bowles (1997) argue that IT architectures built around adaptive learning problem resolution architectures can provide a basis toward building faster-learning knowledge-creating organizations in the electronic economy (in the context of customer support process redesign). However, their argument cannot be effective without creative people. Creative people create knowledge with the enabling power of IT (Couger, 1996). IT architectures can be built around adaptive learning processes, but this must be accompanied by a consideration for those who create the knowledge. It is hard to argue against the importance of effective customer support process improvement, but it should be tempered with the facilitative IT perspective and a desire to develop the skill sets and abilities of the individuals along the process redesign path. Given that the role of technology is to facilitate business processes (Davenport, 1993) and that the end goal of BPR is to delight the customer (Davenport, 1993; Drucker, 1989; Hammer & Champy, 1993; Paper & Dickinson, 1997) it is imperative not to lose site of the importance of developing process workers and somehow extracting the knowledge they gain by being intimately involved in the effort.

Transformation (Change) Vision

Vision (Figure 6) offers a means of communicating the reengineering philosophy to the entire organization by pushing strategic objectives down to the process level and aligning the project with business goals. Harkness et al. (1996) refer to transformation vision as a "grand strategy" for business transformation. Their perspective of a "grand strategy" encompasses new policies, new operating procedures, and a vision that cannot be readily generalized from context-to-context (Earl, Sampler, & Short, 1995). It is important for those involved in the change effort to understand how it will unfold and how it will affect them as individuals (Caron et al., 1994). As such, employees at all levels should be involved in design and analysis (Caron et al., 1994). Davenport and Short (1990) add that top-down design is ineffective unless the people who do the work are involved (Davenport & Stoddard, 1994). Further, people who do the work at the process level must understand the business to help alignment with business objectives (Paper & Dickinson, 1997).

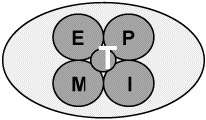

Figure 6: Transformation component model

If the change vision is holistic, work is viewed as part of the whole system (Teng et al., 1998). The underlying goal of a holistic change vision is to align employee goals with those of the organization and vice versa (Drucker, 1989, 1998). It has been argued however that a broad strategic vision is too diluted to guide employees (Cross et al., 1997). Bartlett and Ghoshal (1994) argue that a vision can be too focused which leads to my opia and inflexibility. They suggest a more balanced approach (purpose) that tempers broad vision with "hard" financial realities. Davenport and Stoddard (1994) agree that top-down imperatives should be tempered with involvement from people along the process path. Change manage-ment, however, is very difficult because people tend to react negatively to it (Topchik, 1998). Further, cultural change is the most difficult challenge of BPR (Caron et al., 1994). Hence, atop-down vision tempered with involvement from process workers is imperative because it helps people understand the reasons for change. If people believe that change will benefit them and/or the organization, negativity is reduced. Top management has in its power the ability to influence how the organization perceives environment, people, IT, and methodology. As such, they are responsible for developing, communicating, and deploying the vision as well as making the resources available to process workers to effectively do their job.

Vision can help open communication channels between IT and top management. One cannot be successful without frequent interactions between top management and IT change advocates (Markus & Benjamin, 1996). Open communication can help inform top management of political obstacles, training issues, and budget problems before they stymie the project. It can also help top management disseminate information about the business and BPR progress across the organization. The more informed people are about the business, the better they feel about what they do.

Top management should sell the vision to key stakeholders (process workers, management, stockholders, etc.) before they try to implement change (Beer, Eisenstat, & Spector, 1990). However, change brings many events that cannot be anticipated. Hence, Orlikowski and Hofman (1997) argue that the vision should account for both anticipated and unanticipated change. That is, the vision must be improvisational (Clark et al., 1997). Top management must be flexible enough to understand that the vision is "organic." The vision may have to change dramatically as more is learned about new ways of doing business.

|

| < Day Day Up > |

|

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 174