88 - Surgery for the Management of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis and Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Infections of the Lung

Editors: Shields, Thomas W.; LoCicero, Joseph; Ponn, Ronald B.; Rusch, Valerie W.

Title: General Thoracic Surgery, 6th Edition

Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

> Table of Contents > Volume II > Section XVI - Carcinoma of the Lung > Chapter 103 - Clinical Presentation of Lung Cancer

Chapter 103

Clinical Presentation of Lung Cancer

Matthew G. Blum

As one of the most common malignancies in the world, lung cancer presents with widely varied signs, symptoms, and syndromes. Early lung cancer is rarely symptomatic. Consequently, most patients present in advanced stages with metastases and ultimately die of their disease. The high prevalence of lung cancer and its usually late presentation make it the most common cause of cancer deaths in both men and women. Early symptoms are generally not specific and frequently mimic more common diseases. Historically, screening for lung cancer has not improved survival. However, screening tools such as low-dose computed tomographic (CT) scanning and molecular markers may become more widely used. Lung cancer detection, whether by screening or clinical presentation, can only be accurate if there is a high index of suspicion in the appropriate setting.

While tobacco smoking is clearly recognized as a major cause of lung cancer, several other patient characteristics have been related to particular aspects of lung cancer. Loeb and colleagues (1984) reviewed evidence for smoking as the major risk factor for developing lung cancer. Janerich and colleagues (1990) suggested that high levels of secondhand smoke are also a risk factor for developing lung cancer. Miners of various substances (gold, chromium, nickel, asbestos, uranium) and patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease are also at increased risk. Mayne (1999) and Yang (1999) and their colleagues both published studies suggesting a familial predilection for developing lung cancer even in nonsmokers.

The incidence of lung cancer increases with age. Young patients (less than 40 years old), women, and nonsmokers are more likely to have their symptoms attributed to benign causes. Whooley (1999), Bourke (1992), and Pemberton (1983) and their colleagues noted that this lower index of suspicion probably accounts for those younger than 40 presenting with higher-stage disease. However, Liu (2000) and Awadh-Behbehani (2000) and their colleagues found no significant difference in survival, stage for stage, between very young and older patients. Kuo and colleagues (2000) found that lung cancers in patients younger than 40 are more common in women. Kuo (2000), Whooley (1999), and Bourke (1992) and their co-workers also found adenocarcinoma more frequently in those younger than 40 who developed lung cancer. The increasing number of women smokers has resulted in a parallel increase in the prevalence of lung cancer in women. Women have a higher incidence of adenocarcinoma and may survive longer in earlier stages, as described by de Perrot and colleagues (2000).

The increasing use of helical CT and high-resolution CT scanning as a lung cancer screening tool (Chap. 49) and in the evaluation of other medical conditions may be increasing the incidence of asymptomatic lesions detected. Despite this, 93% of lung cancer patients still present with symptoms. A large variety of symptoms has been associated with lung cancer. Only 27% of patients will have local symptoms from the primary tumor; 32% have symptoms from metastases, and 34% have nonspecific symptoms. Paraneoplastic syndromes occur in 2% of patients with lung cancer.

LOCAL SYMPTOMS

Bronchopulmonary Symptoms

Cough

Cough is the most common presenting symptom of lung cancer (Table 103-1), but it is frequently overlooked because it is far more frequently associated with infections or chronic bronchitis. Cough itself is caused by airway irritation. Mass effect, inflammatory response to cancer, and obstruction-causing pneumonia may all be active in causing cough. Smokers frequently have a chronic cough, but changes in the character (sputum production, frequency) of the cough should prompt further evaluation. There are no particular characteristics that distinguish benign from malignant causes of cough.

Hemoptysis

Hemoptysis is generally an alarming symptom that leads to rapid presentation to the medical system. Inflammatory

P.1509

diseases still account for most cases of hemoptysis, although the rising incidence of lung cancer makes it increasingly responsible for hemoptysis. Herth and colleagues (2001) reviewed 722 patients referred to a pulmonologist for evaluation of hemoptysis. Forty percent had lung cancer. Of those who had no bleeding source found during the initial evaluation, 6% ultimately had lung cancer. Bronchoscopy and chest radiography should be used routinely to evaluate hemoptysis. A CT scan of the chest should follow a negative bronchoscopic examination and chest radiograph.

Table 103-1. Intrathoracic Signs and Symptoms of Lung Cancer | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Hemoptysis from lung cancer is generally small to moderate in volume (less than 500 mL per 24 hours), as noted by Hirshberg and colleagues (1997). Hemoptysis is present at the time of presentation in 9% to 57% of patients with bronchogenic cancer, as reported by LeRoux (1968) and Hyde and Hyde (1974), as well as by Chute (1985), Lam (1983), and Weiss (1978) and their co-workers. Possible sources of hemoptysis include systemic supply from the bronchial arteries or collaterals and pulmonary supply from the pulmonary artery or veins. Severe systemic arterial bleeding may be controlled by embolization. However, Hayakawa and colleagues (1992) found that the frequently multisource blood supply of carcinoma-induced hemoptysis resulted in decreased success of embolization when compared with other causes of hemoptysis. The same study also reported that patients with lung cancer and hemoptysis requiring embolization survive less than 4 months. Erosion of tumor into pulmonary arteries or systemic vessels is often massive and fatal. Miller and McGregor (1980) reported erosion into the heart itself as a cause of fatal hemoptysis. Despite these reports, lung cancer is rarely a cause of massive hemoptysis.

Wheezing or Stridor

Lung cancer can cause airway obstruction and turbulent airflow, resulting in the harshness of stridor or musical wheezing. Both intrinsic obstruction by tumor mass and extrinsic airway compression by tumor or adenopathy may cause obstruction. Stridor generally indicates tracheal obstruction and occurs when more than 50% of the lumen is obstructed. Occasionally central main-stem bronchial tumors may create stridor. Wheezing caused by lung cancer (in contrast to polyphonic, diffuse asthmatic wheezing) is often monophonic and localized around the area of obstruction. Both stridor and wheezing from tumors involving the trachea are occasionally diagnosed as adult-onset asthma. Stridor is an inspiratory noise and should not be mistaken for the expiratory wheezing of asthma. Neither stridor nor wheezing caused by cancer responds well to bronchodilators. Chest radiographs are often unrevealing. A CT scan or bronchoscopy is usually required to make the diagnosis.

Dyspnea

Lung cancer may cause dyspnea by multiple different mechanisms. Airway obstruction can cause atelectasis distal to the obstruction. The amount of lung parenchyma involved may vary from only a subsegmental area of lung parenchyma to an entire lung, depending on the site and degree of airway obstruction. Similarly, obstruction or compression of the pulmonary artery or branches may result in areas of defunctionalized lung secondary to hypoperfusion. Ventilation-perfusion mismatch in either case may cause dyspnea. Postobstructive pneumonia can similarly result in dyspnea. Additionally, tumor infiltration of lung parenchyma or increased lung water from inhibition of lymphatic drainage can result in increased alveolar thickness, less efficient gas diffusion, and relative shunting. Pleural effusions frequently cause dyspnea. Symptomatic effusions from lung cancer most commonly contain malignant cells. Less common causes of dyspnea are phrenic nerve paralysis and pericardial effusion.

Postobstructive Infectious Symptoms

Tumors that obstruct airways inhibit airway drainage, allowing colonization and overgrowth of bacteria. The resulting postobstructive pneumonia can cause fever and leukocytosis, malaise, and weight loss. Chest imaging may be unable to reliably distinguish tumor mass from the pneumonic process. Therefore, patients treated with antibiotics should have a follow-up radiograph to confirm complete resolution of infiltrates. Recurrent pneumonia in the same location should prompt CT scanning and bronchoscopy to exclude an anatomic basis for recurrence.

Nonbronchopulmonary Symptoms

Pain

Chest wall pain may bring patients to medical attention. Pleural-based pain may be due to direct irritation of the

P.1510

parietal pleura by either inflammation from postobstructive pneumonia or direct invasion by tumor. Tumor invasion or metastasis to ribs may create bone pain. Additionally, sensory nerve invasion (intercostal or brachial plexus) can lead to neuropathic pain. Chest wall pain in the region of known tumor should raise the suspicion of chest wall invasion. Preoperative evaluation should include imaging of the region to define depth of invasion and involved structures. When complex neurovascular structures are involved (such as the apex of the chest or spine), magnetic resonance (MR) imaging provides better anatomic definition than CT scanning. Operations on patients who have chest wall pain should include a strategy for en bloc chest wall resection. Bindoff and Heseltine (1988) reported diffuse facial pain from lung cancer invasion of the ipsilateral vagus nerve. In eight cases, facial pain preceded diagnosis by 6 weeks to 4 years and was relieved by radiation treatment of the primary tumor.

Pancoast Tumors

Superior sulcus tumors may invade the brachial plexus and stellate ganglion, presenting with a constellation of signs and symptoms known as Pancoast's syndrome. These include ipsilateral Horner's syndrome (facial anhydrosis, miosis, and ptosis) as well as neuritic pain and muscular atrophy in the arm and hand. Horner's syndrome is caused by direct tumor invasion of the stellate ganglion. Tumor invasion of the lower brachial plexus cords (C7, C8, T1) leads to inner arm pain and wasting of intrinsic muscles of the hand. Vertebral body or rib destruction results in bone pain. Direct invasion of intercostal nerves can also cause chest wall and inner arm (via tracheocutaneous branch) pain. Komaki and colleagues (2000) reported on 143 patients with superior sulcus tumors presenting for evaluation at M. D. Anderson. Nineteen percent had Horner's syndrome, and 69% had chest pain. Although locally invasive, Pancoast tumors are frequently amenable to treatment with multimodality therapy, including surgical resection (Chaps. 106, 110, 113).

Dysphagia

Dysphagia occurs rarely as a presenting complaint of lung cancer. When it does occur, it is usually due to esophageal compression or invasion from subcarinal nodal disease. More rarely, direct extension of tumor or involvement of paraesophageal nodes causes obstruction.

Other Local Findings

Pleural Effusion

Patients with dyspnea from lung cancer frequently have a malignant pleural effusion. The typically one-sided effusions result from an imbalance of pleural fluid production and resorption. Cancer patients may develop effusions from (a) increased capillary permeability from tumor implants, (b) decreased oncotic pressure from hypoproteinemia, or (c) decreased absorption secondary to lymphatic obstruction by tumor (Chap. 58). The survival of patients presenting because of malignant pleural effusion is poor. Monte and co-workers (1987) reported that all 12 patients who had the initial diagnosis of lung cancer due to malignant pleural effusion died within 19 months of diagnosis. Pleural effusions associated with lung cancer can be reactive, especially in the setting of postobstructive atelectasis or pneumonia.

Thoracentesis and fluid cytology is indicated to establish the presence or absence of malignant cells prior to resection and in any cases where such staging would change the therapeutic plan. Occasionally, an effusion will be discovered incidentally as a radiographic abnormality and prompt additional evaluation that ultimately leads to the diagnosis of lung cancer. Monte and colleagues (1987) reported on cytology results in 860 pleural effusion specimens in patients without known lung cancer. Two percent of patients had their initial diagnosis of lung cancer made based on malignant cells in the effusion. This is likely to be lower in the current era with the increased availability of CT scans. Mesothelioma frequently presents with malignant pleural effusion. Pleural biopsy is encouraged to evaluate recurrent pleural effusions with nondiagnostic cytology.

Pericardial Effusion

Although tumor invasion of the pericardium is frequent in patients who die with lung cancer, it is rarely the presenting problem. Lung cancer is the most common cause of malignant pericardial effusion. Both transudative and exudative effusions may be caused by lung cancer. Pericardial seeding combined with lymphatic obstruction causes the accumulation of fluid. Bloody pericardial effusions are nearly always malignant. Although malignancy may cause a large pericardial effusion, if fluid production is relatively slow the pericardium can enlarge to accommodate the fluid without tamponade. Tamponade is usually the result of rapid fluid accumulation or bleeding into the relatively indistensible pericardium. Huntsman and colleagues (1991) reviewed 65 reported cases of tamponade as the initial presentation of lung cancer. This is typically associated with poor prognosis. In a review by Muir and Rodger (1994), patients whose malignancies presented as cardiac tamponade survived an average of 144 days.

Superior Vena Cava Syndrome

In the modern era, lung cancer has replaced inflammatory diseases as the most common cause of superior vena cava (SVC) syndrome. Symptoms include a feeling of fullness and swelling in the face and arms. Frequently, this worsens when the patient is recumbent (e.g., at night) and improves with head elevation. Distended neck veins and

P.1511

large superficial chest and neck collaterals may be present. SVC syndrome may develop insidiously as the SVC is slowly compressed and collateral pathways enlarge. Rapidly growing tumors or those that cause thrombosis typically are associated with worse symptoms because collaterals have insufficient time to develop. SVC thrombosis usually results from direct SVC compression by tumor or adenopathy. However, SVC invasion by tumor may also create a nidus for thrombus formation.

SVC syndrome is very rarely an emergency, and correct diagnosis of the underlying cause should be made to provide rational treatment. Diagnosis of the inciting cause usually involves obtaining tissue by needle biopsy, bronchoscopy, or mediastinoscopy. Little (1985) and Jahangiri (1993) and their colleagues noted that mediastinoscopy is generally a safe procedure in patients with SVC syndrome. The pretracheal plane is typically not heavily involved by collateralization. Bleeding resulting from disrupted collaterals is of low pressure and easily controlled. SVC syndrome caused by non small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) usually indicates unresectability.

SYMPTOMS FROM METASTATIC DISEASE

Lung cancer is frequently metastatic at the time of diagnosis. Metastases have been reported in every organ and in an abundance of musculoskeletal locations. Frequently, lung cancer metastases cause the presenting signs or symptoms that inspire the search for a primary tumor. The most common sites of extrathoracic metastases are the brain, bones, adrenal glands, and liver. Autopsy series correlating the frequency of metastases with histologic type show the highest incidence of metastatic disease with small cell carcinoma, followed by anaplastic large cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, and squamous carcinoma (Table 103-2). Metastatic disease generally precludes curative operation for lung cancer. This is particularly true when the metastasis is the reason for presentation. Occasionally, resection of an isolated synchronous metastasis and resection of the primary tumor have led to long-term survival (Chap. 106).

Bone Metastases

Lung cancer metastases to nearly every bone have been reported. The axial skeleton and long bones are the most common sites. Metastases to bones of the hands and feet are rare. Bone pain is the usual symptom. Pathologic fractures occasionally herald the presence of lung cancer. Plain radiographs; bone scans; and positron emission tomographic (PET), CT, and MR imaging may all be helpful in diagnosing bone metastases. Nuclear medicine studies are sensitive, but not highly specific, and should be correlated with anatomic studies or biopsy or both. Lung cancer metastases are generally osteolytic, although some tumors do create osteoblastic lesions. Metastases may present as arthritis when synovium or juxtaarticular bone is involved. Bony collapse of the spine with ensuing nerve involvement may warrant operative reconstruction to prevent further neurologic injury.

Table 103-2. Frequency (%) of Metastatic Disease at Autopsy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Neurologic Metastases

Metastases cause a wide variety of neurologic symptoms (Table 103-3). Ten percent of patients have central nervous system metastases at the time of diagnosis. Merchut (1989) found that symptomatic brain metastases from an unknown primary tumor most frequently arise from lung cancer. Symptoms are generally caused by an increase in intracranial pressure (e.g., headache, nausea, blurred vision or diplopia, changes in mental status). Focal neurologic

P.1512

deficits or pain due to meningeal or bony invasion are less common. Although small cell lung cancers are most likely to metastasize to the brain, adenocarcinomas, because of their higher prevalence, have the highest incidence of brain metastases. Reyes and colleagues (1999) reported on 137 patients who had a solitary brain metastasis as their presentation of lung cancer. The histologic distribution was as follows: adenocarcinoma, 76%; small cell, 20%; and squamous and large cell, 2%. Both CT and MR imaging can be used to identify brain metastases, but MR imaging is more sensitive. PET scans may be negative because of the high metabolic rate of background neurologic tissue.

Table 103-3. Etiology of Neurologic Symptoms Associated with Metastasis | |

|---|---|

|

Carcinomatous meningitis is a rare presentation of lung cancer. This most frequently develops in the course of small cell lung cancer (SCLC). Symptoms include changes in mental status, seizures, headaches, cranial neuropathies, weakness or sensory changes, bowel or bladder dysfunction, and back pain. CT scans are usually normal, but cerebrospinal fluid cytology is diagnostic.

Intramedullary spinal cord metastases are uncommon but may cause significant neurologic deficits. SCLC has a greater propensity to metastasize to the spinal cord than NSCLC. MR is the diagnostic imaging study of choice. Murphy (1983) and Potti (2001) and their colleagues noted that treatment of both NSCLC and SCLC intramedullary metastases by radiation therapy is effective.

Spinal epidural metastases (SEMs) occur relatively frequently in the setting of malignancy. External compression of the spinal cord or cauda equina causes back pain and radiculopathy or myelopathy. SEMs are most commonly observed in the course of prostate or breast cancer. However, Schiff and colleagues (1997) found that the lung is the most common primary site in patients who have symptoms from SEMs as their initial presentation of malignancy. Plain radiographs, CT scanning, myelography, MR imaging, and bone scanning may all be useful in diagnosing SEMs. CT-guided needle biopsy of spinal lesions is generally successful. Because paraneoplastic and nonmalignant processes may cause symptoms similar to those caused by SEMs, metastases should be confirmed by the appropriate studies. Most metastases can be treated with radiation therapy. Surgical resection and reconstruction may be useful in cases of spinal instability due to bony destruction.

Adrenal Metastases

Adrenal masses are usually asymptomatic. When more than 90% of adrenal tissue is replaced by tumor, symptoms of insufficiency (Addison's syndrome) may develop. Generally, metastases are found during CT scanning for staging evaluation. Adrenal adenomas are also commonly found on staging examinations. Differentiation between adenomas and metastases may be made by chemical shift MR imaging or PET scanning. Adenomas tend to have little or no increase in signal on PET scan, and on chemical shift MR imaging, microscopic fat may be identified that is present in adenomas but not in metastatic disease. Silverman and colleagues (1993) found that CT-guided needle biopsy of suspicious adrenal lesions is 96% accurate.

Liver Metastases

Liver metastases are generally asymptomatic until very late in the course of lung cancer. Most commonly they are found during staging CT scanning. PET scans are also effective at detecting liver metastases and are helpful in differentiating malignant from benign nodules that are indeterminate on CT scans. Lesions that are hot on PET scan and visible on CT scan should undergo biopsy if the presence or absence of metastatic disease would modify management. Symptoms associated with liver metastases include abdominal pain, anorexia, jaundice, ascites, hepatomegaly, and liver failure.

Other Sites

Lung cancer metastases have been reported in every organ. Complications from the metastases may be the initial presentation of lung cancer. Small-bowel metastases causing perforation, as recorded by Mosier and associates (1992), and melena, as noted by Berger and colleagues (1999), have been reported as the first sign of lung cancer. Gutman and colleagues (1993) reported a patient in whom acute pancreatitis was the presentation of large cell lung carcinoma.

Soft tissue metastases may also be the presenting lesion for lung cancer. Kelly and colleagues (1988) reviewed the world literature on breast lumps as the first presentation of nonbreast malignancy. Twenty of 42 were from lung cancer. Of these, 16 were small cell lung cancer. Rose and Wood (1983) as well as Sweldens and colleagues (1992) reported lung cancer metastases to the soft tissues of the fingertips as the presentation of lung cancer. Usually such metastases indicate advanced disease, with a correspondingly poor prognosis.

Paraneoplastic Syndromes

Undoubtedly the most unusual and most intriguing symptoms are the result of paraneoplastic processes. Approximately only 2% of lung cancer patients develop paraneoplastic syndromes. Even small-volume lung cancers can produce secretory products and invoke immune responses that can have varied and distant end-organ effects (Table 103-4). Paraneoplastic signs and symptoms may be present even before any lung masses are visible on imaging studies.

P.1513

This section discusses a few of the more common paraneoplastic syndromes associated with lung cancer (Table 103-5).

Table 103-4. Paraneoplastic Syndromes in Lung Cancer Patients | |

|---|---|

|

Syndrome of Inappropriate Antidiuretic Hormone Secretion

Syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH) causes hyponatremia and can result in symptoms (nausea, seizures, altered mental status, and lethargy progressing to coma). Elevated levels of antidiuretic hormone are common in patients with lung cancer, but infrequently result in symptoms. De Troyer and Demanet (1976) and List and colleagues (1986) found that SIADH is more common with SCLC and in women. Diagnosis is made by demonstrating hyponatremia in the setting of high urinary sodium excretion. Acute treatment of symptomatic SIADH consists of fluid restriction and administration of demeclocycline to block the action of antidiuretic hormone at the renal tubule. Treatment of the primary tumor generally resolves the SIADH.

Table 103-5. Frequency of Paraneoplastic Endocrine Syndromes | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Hypercalcemia

Hypercalcemia may result from either metastatic bony destruction or from bone resorption due to ectopic parathormone (PTH) or parathyroid hormone related protein (PTH-rp) production. Ten percent of lung cancer patients develop hypercalcemia during the course of their disease. However, only 12.5% to 15% of these patients will have hypercalcemia due to PTH production. Squamous cell carcinomas are most frequently responsible. Symptoms include nausea, constipation, anorexia, polydipsia, polyuria, irritability, and altered metal status, including unconsciousness and coma. Signs of hypocalcemia include hyporeflexia and cardiac dysrhythmias. As with other paraneoplastic syndromes, treatment of tumors that produce PTH results in the alleviation of hypercalcemia.

A relation appears to exist among PTH-rp levels, hypercalcemia, and bony metastases. Hiraki and colleagues (2002) examined PTH-rp levels at the time of presentation in 23 patients with hypercalcemia and lung cancer. Seventy-one percent of patients with PTH-rp levels higher than 150 pmol/L had bony metastases, versus 12.5% in patients with PTH-rp levels below 150 pmol/L. Elevated PTH-rp levels also correlated with decreased mean survival (1.4 months vs. 5.4 months). The cause and effect relationship of PTH-rp on bone metastases has yet to be elucidated.

Cushing's Syndrome

Tumor production of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) occurs primarily in SCLC. Because ACTH levels rise rapidly, the classic manifestations of Cushing's syndrome do not have time to develop. Shepherd and colleagues (1992) noted that edema and muscle weakness are

P.1514

frequently the first clinical signs. The metabolic consequences of excess ACTH production predominate, including hypokalemia, metabolic alkalosis, hyperglycemia, elevated blood cortisol levels, and elevated ACTH levels. The tumors secrete ACTH autonomously; consequently, ACTH and cortisol levels are not suppressed by dexamethasone administration.

Clubbing and Hypertrophic Pulmonary Osteoarthropathy

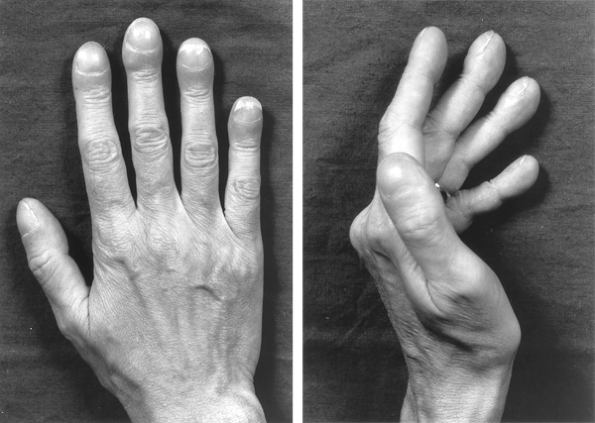

Digital clubbing is often found in association with NSCLC, particularly with squamous cell tumors (Fig. 103-1). However, hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy occurs only in a small subset of those with clubbing. Clubbing is not specific for lung cancer and may be caused by cyanotic heart disease or chronic lung disease. Hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy, however, is almost always associated with lung cancer, usually adenocarcinoma. Rarely, hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy is also seen with chronic lung disease. Various other tumors of the lung and pleura, especially solitary fibrous tumors of the pleura, may be associated with osteoarthropathy.

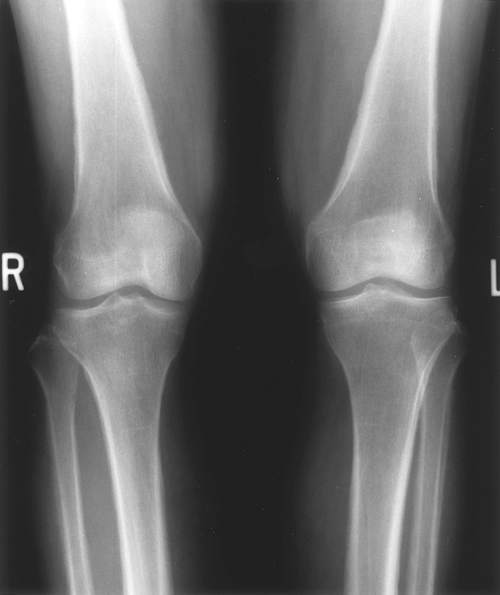

Hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy is characterized by long bone periosteitis, particularly of the radius, ulna, tibia, and fibula. Typically occurring at the distal end of the bone, the inflammation results in swelling and pain over the affected area. Plain radiographs show periosteal elevation and new bone formation (Fig. 103-2). Bone scans will show increased activity in the affected areas (Fig. 103-3).

|

Fig. 103-1. Hands of patient with lung cancer, demonstrating clubbing with increased nail base angle to 180 degrees and fusiform enlargement of the distal digit (so-called drumstick fingers). |

|

Fig. 103-2. Radiograph of the distal femur of a patient with lung cancer presenting with hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy, illustrating periosteal elevation and new bone formation. |

Hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy and clubbing may precede the diagnosis of cancer by several months. Often the pain resolves rapidly after resection. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory agents may also provide significant relief. Carroll and Doyle (1974) reported that proximal ipsilateral vagotomy can relieve associated pain in unresectable tumors. A further discussion of this syndrome is presented in Chapter 64.

Neurologic and Myopathic Syndromes

The most common neurologic paraneoplastic syndromes are encephalomyelitis and sensory neuropathy. These syndromes are most likely immune mediated. SCLC and, to a lesser extent, squamous cell lung cancers are the most common inciting tumor types. Fifteen percent of patients with lung cancer may be found to have neuropathy when carefully questioned and examined. Frequently, however, these syndromes are present in conjunction with advanced-stage tumors. Brain or neurologic metastases, general cachexia, or other complications of lung cancer may be the underlying cause of the neuropathy. CT or MR imaging should be used to rule out neurologic metastases in patients with neuromuscular deficits.

|

Fig. 103-3. Bone scan of a patient with lung cancer, illustrating the classic appearance of symmetric increased uptake of the radioisotope in the periosteum of the distal femur and proximal tibia. |

P.1515

Neurologic paraneoplastic syndromes have been associated with anti-Yo, anti-Ri, and anti-Hu (Hu-Ab) antibodies (Table 103-6). The antibodies to tumor antigens cross-react with neuronal nuclei and cause inflammatory responses that result in neuronal cell death. Sillevis Smitt and colleagues (2002), reporting on 73 Hu-Ab-positive patients, noted that the neurologic symptoms preceded the diagnosis of cancer by 3.5 months. Sensory neuropathy (55%), cerebellar ataxia (22%), limbic encephalitis (15%), brainstem encephalitis (8%), and global encephalitis (8%) were the presenting symptoms. Thirty-two percent of patients had multifocal neurologic deficits at presentation. Lung tumors were noted in 56 patients. SCLC was confirmed histologically in 38. Treatment with immunomodulation (steroids, intravenous immunoglobulin, plasma exchange, and cyclophosphamide) tends to be ineffective, but patients often have improvement of their neurologic symptoms with treatment of the tumor. Despite significant improvement in symptoms, deficits often persist due to irreversible peripheral and central nerve cell death.

Myopathies causing muscle weakness are also most frequently associated with SCLC. They generally result in proximal muscle weakness. Two mechanisms have been noted: a myositis with general degeneration of muscle fibers, and a myastheniclike syndrome resulting from a defect in neuromuscular transmission. Muscle wasting is most prominent in myositis (Table 103-7).

Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome is most commonly associated with SCLC. As the name implies, it is characterized by myastheniclike symptoms of proximal muscle weakness, autonomic dysfunction, dysarthria, ptosis, and blurred vision. It may precede the diagnosis of cancer by years. Antibodies are created against voltage-gated calcium channels that consequently inhibit presynaptic release of acetylcholine at the motor endplate. Antitumor therapy has a variable effect. For those with refractory symptoms, treatment with 3,4-diaminopyridine, guanidine hydrochloride, or immunosuppressive agents may be helpful.

Anemia and Hematologic Abnormalities

Multiple hematologic abnormalities are associated with lung cancer. Silvis and colleagues (1970) found that thrombocytosis may occur in as many as 60% of lung cancer patients. Normochromic normocytic anemia is present in 20% of lung cancer patients, as reported by Zucker and colleagues (1974). Decreased iron use, shortened red cell survival, and decreased serum iron and iron binding capacity all contribute to the anemia. Other hematologic abnormalities associated with lung cancer include sideroblastic anemia, hemolytic anemia, red cell aplasia, erythrocytosis, leukemoid reactions, eosinophilia, thrombocytopenia, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, and disseminated intravascular coagulation.

Trousseau's Syndrome and Acute Arterial Thrombosis

Hypercoagulable states have long been recognized in association with solid organ tumors since a description by Trousseau (1865). Lung cancer is commonly associated with hypercoagulability and may present with vascular thrombosis. Superficial thrombophlebitis and deep venous thromboses are the most frequent manifestations. Malignancy-related venous thrombosis should be suspected when unusual sites (inferior vena cava, jugular vein, arm veins) or patterns (recurring or migratory thrombosis) are present. Arterial thrombosis carries a particularly poor prognosis. Rigdon (2000) noted that tumor-related arterial thrombosis frequently results in limb ischemia and often rethrombosis that ultimately requires amputation. Naschitz and colleagues (1992)

P.1516

noted that thrombosis as a result of paraneoplastic syndrome can be refractory to anticoagulation. In most cases, the biochemical cause of the hypercoagulable state cannot be identified. Treatment of the primary tumor may reverse the hypercoagulable state.

Table 103-6. Autoantibodies Associated with Neurologic Paraneoplastic Syndromes and Lung Cancer | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Tumor or thrombotic emboli may occur in both the pulmonary and systemic circulations. Pulmonary emboli typically originate from deep venous thromboses. Systemic emboli may be paradoxical or a result of tumor fragments or thromboemboli released into the pulmonary venous circulation. Occasionally, nonbacterial thrombus with or without tumor may occur inside the heart in association with lung cancer. Embolic phenomena and thrombotic endocarditis are generally indicators of advanced disease.

Dermatologic Manifestations

A multitude of dermatologic abnormalities are associated with lung cancer. They frequently develop rapidly and are most commonly associated with adenocarcinoma. The most common manifestations are dermatomyositis, erythema gyratum, and lanuginosa acquisita. The skin condition often precedes the diagnosis of lung cancer by several months.

Table 103-7. Paraneoplastic Neuromuscular Syndromes | |

|---|---|

|

Autoimmune Syndromes

In addition to the specific manifestations mentioned previously, tumor-related autoantibody production may result in other autoimmune syndromes. Often these syndromes are the presenting complaint. Odeh (2001), Blanco (1997), and Enzenauer (1989) and their colleagues reported cutaneous leukocytoclastic vasculitis, Henoch-Sch nlein purpura, and systemic sclerosis as the initial manifestation of lung cancer. Frequently, treatment of the tumor either with resection or chemotherapy results in relief of the autoimmune syndrome.

Miscellaneous Manifestations

Several other paraneoplastic conditions occur with lung cancer. The most common renal abnormality is nephrotic syndrome. Anorexia, cachexia, and fatigue all occur frequently and are generally associated with advanced disease. The pathogenesis is multifactorial.

ASYMPTOMATIC PATIENTS

Asymptomatic patients who have lung cancers found on screening studies, either as part of screening programs or during evaluation for other medical conditions, generally have earlier-stage tumors than those who present with symptoms. Because lower-stage lung cancers have better resectability and survival rates, it is frequently assumed that patients detected in such a fashion will have improved survival. However, as lung cancers are detected at earlier stages, it is unclear if current treatment strategies will result in improved survival or merely demonstrate lead-time bias. In the future, molecular screening and cellular and subcellular targeted therapy may result in improved survival. In the meantime, the presentation of an asymptomatic patient with early lung cancer is becoming a more frequent scenario.

P.1517

Screening

Tockman (2000), analyzing archived screening sputa, showed that alterations in gene expression appear to be present long before the development of clinically evident lung cancer. This raises the possibility that sputum screening may permit extremely early lung cancer detection, or at least provide a more specific population for intensive screening.

Satoh and colleagues (1997) in a 20-year, retrospective study of 561 lung cancer patients, analyzed outcomes based on presentation. Patient groups included those with cancers found on screening chest radiographs, those presenting with symptoms, and those who had their cancers found while being evaluated for other conditions. Seventy-two percent of cancers in patients in the screening group were operable, compared with 24% of those found because of symptoms. The Kaplan-Meier survival at 6 years for the screened group was 32% versus 8% for the symptomatic group. Interestingly, the survival rate in the group who had cancer incidentally diagnosed during evaluation for other conditions was no different from the rate in those who presented with symptoms. Salomaa (2000), reporting a similar series from Finland, showed a 5-year survival of 19% for screened cases and 10% for those presenting with symptoms.

Henschke (1999), Sone (2001), and Sobue (2002) and their colleagues, using low-dose CT scanning, have suggested that early lung cancers may be effectively detected before development of symptoms in selected populations. Mahadevia and colleagues (2003), using a mathematical model, have questioned the cost-efficiency and the ultimate effectiveness of CT as a screening tool. The ultimate role of screening for lung cancer has yet to be determined.

Currently, many asymptomatic patients undergoing screening CTs, CT scanning for coronary disease, and radiologic imaging for other conditions are found to have lung cancer. Often these cancers are at early stages that permit surgical resection for cure. Although issues of lead-time bias and the unknown biologic behavior of these early cancers have not been fully addressed, the most sensible approach is to evaluate suspicious nodules appropriately. There is not good evidence to suggest that a less aggressive approach to these early lung cancers is warranted.

The lethality of early (stage I) lung cancer is supported by the review of Flehinger and coinvestigators (1992) of the three early screening trials conducted in North America that were reported by Fontana (1986) and Melamed (1984) and their collaborators and by Tockman (1986). In these three trials, 45 clinical stage I patients did not undergo surgical resection of their disease for one or more reasons, and only 2 of these patients survived 5 years. In addition, Sobue and colleagues (1992), who reported the survival of patients with clinical stage I disease detected by screening versus those detected because of symptoms, found 69 clinical stage I disease patients who likewise did not undergo surgical resection of their disease; only 7 of these patients survived 5 years. Thus, in a total of 114 unresected stage I patients, only 9 patients (8%) were long-term survivors. Flehinger and colleagues (1992) note that at least 7% of the unresected group died of unrelated causes, so that one may assume that 85% of the nonsurgically treated patients died of progression of their lung cancer. A statistic such as this supports the contention that early stage I lung cancer is indeed a lethal disease and that so-called lead-time bias and overdiagnosis as the basis for long-term survival after resection of early-stage disease may be effectively questioned.

REFERENCES

Awadh-Behbehani N, et al: Comparison between young and old patients with bronchogenic carcinoma. Acta Oncol 39:995, 2000.

Berger A, et al: Small bowel metastases from primary carcinoma of the lung: clinical findings and outcome. Am J Gastroenterol 94:1884, 1999.

Bindoff LA, Heseltine D: Unilateral facial pain in patients with lung cancer: a referred pain via the vagus? Lancet 1:812, 1988.

Blanco R, et al: Henoch-Sch nlein purpura as a clinical presentation of small cell lung cancer. Clin Exp Rheumatol 15:545, 1997.

Bourke W, et al: Lung cancer in young adults. Chest 102:1723, 1992.

Carroll KB, Doyle L: A common factor in hypertrophic osteoarthropathy. Thorax 29:262, 1974.

Chernow B, Sahn SA: Carcinomatous involvement of the pleura: an analysis of 96 patients. Am J Med 63:695, 1977.

Chute CG, et al: Presenting conditions of 1539 population based lung cancer patients by cell type and stage in New Hampshire and Vermont. Cancer 56:2107, 1985.

Cohen MH: Signs and symptoms of bronchogenic carcinoma. Semin Oncol 1:183, 1974.

de Perrot M, et al: Sex differences in presentation, management, and prognosis of patients with non-small cell lung carcinoma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 119:21, 2000.

De Troyer A, Demanet JC: Clinical, biological and pathogenic features of the syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone. A review of 26 cases with marked hyponatremia. Q J Med 45:521, 1976.

Enzenauer RJ, McKoy J, Riel M: Case report: rapidly progressive systemic sclerosis associated with carcinoma of the lung. Mil Med 154: 574, 1989.

Flehinger BJ, Kimmel M, Melamed MR: The effect of surgical treatment on survival from early lung cancer. Implications for screening. Chest 101:1013, 1992.

Fontana RS, et al: Lung cancer screening: the Mayo program. J Occup Med 28:746, 1986.

Gutman M, Inbar M, Klausner JM: Metastases-induced acute pancreatitis: a rare presentation of cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol 19:302, 1993.

Hayakawa K, et al: Bronchial artery embolization for hemoptysis: immediate and long-term results. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 15:154, 1992.

Henschke CI, et al: Early Lung Cancer Action Project: overall design and findings from baseline screening. Lancet 354:99, 1999.

Herth F, Ernst A, Becker HD: Long-term outcome and lung cancer incidence in patients with hemoptysis of unknown origin. Chest 120:1592, 2001.

Hiraki A, et al: Parathyroid hormone-related protein measured at the time of first visit is an indicator of bone metastases and survival in lung carcinoma patients with hypercalcemia. Cancer 95:1706, 2002.

Hirshberg B, et al: Hemoptysis: etiology, evaluation, and outcome in a tertiary referral hospital. Chest 112:440, 1997.

Hopwood P, Stephens RJ: Symptoms at presentation for treatment in patients with lung cancer: implications for the evaluation of palliative treatment. The Medical Research Council (MRC) Lung Cancer Working Party. Br J Cancer 71:633, 1995.

Huntsman WT, Brown ML, Albala DM: Cardiac tamponade as an unusual presentation of lung cancer: case report and review of the literature. Clin Cardiol 14:529, 1991.

Hyde L, Hyde CI: Clinical manifestations of lung cancer. Chest 65:299, 1974.

Jahangiri M, Taggart DP, Goldstraw P: Role of mediastinoscopy in superior vena cava obstruction. Cancer 71:3006, 1993.

P.1518

Janerich DT, et al: Lung cancer and exposure to tobacco smoke in the household. N Engl J Med 323:632, 1990.

Kelly C, Henderson D, Corris P: Breast lumps: rare presentation of oat cell carcinoma of lung. J Clin Pathol 41:171, 1988.

Komaki R, et al: Outcome predictors for 143 patients with superior sulcus tumors treated by multidisciplinary approach at the University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center. Int J Radiat Oncol 48:347, 2000.

Kuo CW, et al: Non-small cell lung cancer in very young and very old patients. Chest 117:354, 2000.

Lam WK, So SY, Yu DYC: Clinical features of bronchogenic carcinoma in Hong Kong: review of 480 patients. Cancer 53:369, 1983.

LeRoux BT: Bronchial carcinoma. Thorax 23:136, 1968.

List AF, et al: The syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone in small cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 4:1191, 1986.

Little AG, et al: Malignant superior vena cava obstruction reconsidered: the role of diagnostic surgical intervention. Ann Thorac Surg 40:285, 1985.

Liu NS, et al: Adenocarcinoma of the lung in young patients: the M. D. Anderson experience. Cancer 88:1837, 2000.

Loeb LA, et al: Smoking and lung cancer: an overview. Cancer Res 44: 5940, 1984.

Mahadevia PJ, et al: Lung cancer screening with helical computed tomography in older adult smokers: a decision and cost-effectiveness analysis. JAMA 289: 313, 2003.

Matthews MJ: Problems in morphology and behaviour of bronchopulmonary malignant disease. In Israil L, Chahanien P (eds): Lung Cancer: Natural History, Prognosis and Therapy. New York: Academic Press, 1976, p. 23.

Mayne ST, Buenconsejo J, Janerich DT: Familial cancer history and lung cancer risk in United States nonsmoking men and women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 8:1065, 1999.

Melamed MR, et al: Screening for early lung cancer. Results of the Memorial Sloan-Kettering study in New York. Chest 86:44, 1984.

Merchut MP: Brain metastases from undiagnosed systemic neoplasms. Arch Intern Med 149:1076, 1989.

Miller RR, McGregor DH: Hemorrhage from carcinoma of the lung. Cancer 46:200, 1980.

Monte SA, Ehya H, Lang WR: Positive effusion cytology as the initial presentation of malignancy. Acta Cytol 31:448, 1987.

Mosier DM, et al: Small bowel metastases from primary lung carcinoma: a rarity waiting to be found? Am Surg 58:677, 1992.

Muir KW, Rodger JC: Cardiac tamponade as the initial presentation of malignancy: is it as rare as previously supposed? Postgrad Med J 70:703, 1994.

Murphy KC, et al: Intramedullary spinal cord metastases from small cell carcinoma of the lung. J Clin Oncol 1:99, 1983.

Naschitz JE, Yeshurun D, Abrahamson J: Arterial occlusive disease in occult cancer. Am Heart J 124:738, 1992.

Odeh M, Misselevich I, Oliven A: Squamous cell carcinoma of the lung presenting with cutaneous leukocytoclastic vasculitis: a case report. Angiology 52:641, 2001.

Pemberton JH, et al: Bronchogenic carcinoma in patients younger than 40 years. Ann Thorac Surg 36:509, 1983.

Potti A, et al: Intramedullary spinal cord metastases (ISCM) and non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC): clinical patterns, diagnosis and therapeutic considerations. Lung Cancer 31:319, 2001.

Rahim MA, Sarma SK: Pulmonary and extrapulmonary manifestations in delayed diagnosis of lung cancer in Bangladesh. Cancer Detect Prev 7:31, 1984.

Reyes CV, Thompson KS, Jensen JD: Cytopathologic evaluation of lung carcinomas presenting as brain metastasis. Diagn Cytopathol 20:325, 1999.

Richardson GE, Johnson BE: Paraneoplastic syndromes in lung cancer. Curr Opin Oncol 4:323, 1992.

Rigdon EE: Trousseau's syndrome and acute arterial thrombosis. Cardiovasc Surg 8:214, 2000.

Rose BA, Wood FM: Metastatic bronchogenic carcinoma masquerading as a felon. J Hand Surg 8:325, 1983.

Salomaa ER: Does the early detection of lung carcinoma improve prognosis? The Turku study. Cancer 89(suppl 11):2387, 2000.

Satoh H, Ishikawa H, Yamashita YT: Outcome of patients with lung cancer detected by mass screening versus presentation with symptoms. Anticancer Res 17:2293, 1997.

Schiff D, O'Neill BP, Suman VJ: Spinal epidural metastasis as the initial manifestation of malignancy: clinical features and diagnostic approach. Neurology 49:452, 1997.

Shepherd FA, et al: Cushing's syndrome associated with ectopic corticotropin production and small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 10:21, 1992.

Sillevis Smitt P, et al: Survival and outcome in 73 anti-Hu positive patients with paraneoplastic encephalomyelitis/sensory neuronopathy. J Neurol 249:745, 2002.

Silverman SG, et al: Predictive value of image-guided adrenal biopsy: analysis of results of 101 biopsies. Radiology 187: 715, 1993.

Silvis SE, Turkbas N, Doscherholmen A: Thrombocytosis in patients with lung cancer. JAMA 211:1852, 1970.

Sobue T, et al: Survival for clinical stage I lung cancer not surgically treated. Comparison between screen-detected and symptom-detected cases. The Japanese Lung Cancer Screening Research Group. Cancer 69:685, 1992.

Sobue T, et al: Screening for lung cancer with low-dose helical computed tomography: anti-lung cancer association project. J Clin Oncol 20:911, 2002.

Sone S, et al: Results of three-year mass screening programme for lung cancer using mobile low-dose spiral computed tomography scanner. Br J Cancer 84:25, 2001.

Sweldens K, et al: Lung cancer with skin metastases. Dermatology 185: 305, 1992.

Tockman MS: Survival and mortality from lung cancer in a screened population. The Johns Hopkins study. Chest 89:324S, 1986.

Tockman MS: Advances in sputum analysis for screening and early detection of lung cancer. Cancer Control 7:19, 2000.

Trousseau A: Phlegmasia alba dolens. In Clinique Medicale de L'Hotel dieu de Paris, Vol. 3, 2nd Ed. Paris: J. B. Ballilere, 1865.

Weiss W, Seidman H, Boucto KR: The Philadelphia Pulmonary Neoplasm Research Project: symptoms in occult lung cancer. Chest 73:57, 1978.

Whooley BP, et al: Bronchogenic carcinoma in young patients. J Surg Oncol 71:29, 1999.

Yang P, et al: Lung cancer in families of nonsmoking probands: heterogeneity by age at diagnosis. Genetic Epidemiol 17:253, 1999.

Zucker S, Friedman S, Lysik RM: Bone marrow erythropoiesis in the anemia of infection, inflammation, and malignancy. J Clin Invest 53:1132, 1974.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 203