Basics

| In order to better understand the detailed methods of Lean Sigma process improvement, it is important to first have a clear understanding of the basics involved. This begins with simple clarifications of what a process is, how it is defined and then how it is improved. A ProcessThe first thing to point out here is that Lean Sigma is a process improvement methodology, not a function or an activity improvement methodology. This is a key distinction in framing the project and it is one that Champions frequently get wrong during project identification, scoping, and selection. A process is a sequence of activities with a definite beginning and end, including defined deliverables. Also, a "something" travels through the sequence (typical examples include a product, an order, a patient, or an invoice). Resource is used to accomplish the activities along the way. If you can't see an obvious, single process in your project, you might have difficulty applying process improvement to it. The start and end points need to be completely agreed upon between the Belt, Champion, and Process Owner (if this is not the Champion). Clearly, if this is not the case, there will be problems later when the end results don't match expectations. EntitiesIn the preceding definition of a process, there is a "something" that travels along it. For want of a better name, I'll refer to this as an entity. Clearly, this entity can be fundamentally different from process to process, but there seems to be surprisingly few distinct types:

The trick is to be able to identify the Primary Entity as it flows through the process with value being added to it (for example, a patient or perhaps the physical molecules of a product). There will, of course, be secondary entities moving around the process, but focus should be on identifying the primary. Belts sometimes find this difficult when the entity changes form, splits, or replicates. For instance, in healthcare (in the ubiquitous medication delivery process), orders are typically written by the physician and so the Primary Entity is the written order. The order can then be faxed to the pharmacy, and is thus replicated and one copy transmitted to the pharmacy fax machine. The faxed order is then fulfilled (meds are picked from an inventory) and effectively the Primary Entity changes to the medication itself, which will be sent back to the point of request. Similarly, in an industrial setting, we might see the Primary Entity change from customer need to sales order to production order to product. DeliverablesThe last element of the definition of a process is the deliverables. This is often where novice Belts make the biggest mistakes. Simply put, the deliverables are the minimum set of physical entities and outcomes that a process has to yield in order to meet the downstream customers' needs. The single most common mistake Belts make in process improvement is to improve a process based on what customers say they want versus what they truly need (more about this in the section, "Customer Interviewing" in Chapter 7). The deliverables need to be thoroughly understood and agreed upon in the early stages of the project; otherwise later during the analysis of what it is exactly in the process that affects performance, the Belt will have the wrong focus. If your project doesn't have a start, an end, deliverables, or a Primary Entity, it probably isn't a process and you will struggle to apply Lean Sigma to it. Table 1.1 gives examples of good and poor projects across varying industries.

MethodologiesSix Sigma and Lean are both business improvement methodologiesmore specifically, they are business process improvement methodologies. Their end goals are similarbetter process performancebut they focus on different elements of a process. Unfortunately, both have been victims of bastardization (primarily out of ignorance of their merits) and often have been positioned as competitors when, in fact, they are wholly complementary. For the purpose of this practical approach to process improvement

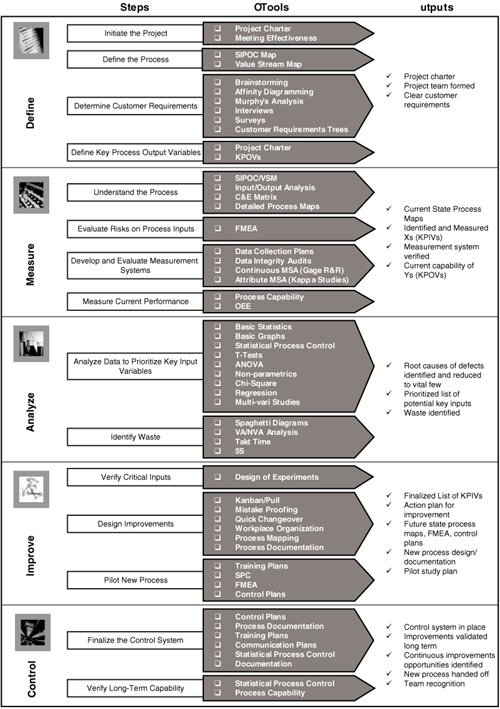

In simple terms, Lean looks at what we shouldn't be doing and aims to remove it; Six Sigma looks at what we should be doing and aims to get it right the first time and every time, for all time. Lean Sigma RoadmapLean Sigma is all about linkage of tools, not using tools individually. In fact, none of the tools are newthe strength of approach is in the sequence of tools. The ability to understand the theory of tools is important, but this book is about how to apply and sequence the tools. There are many versions of the Six Sigma Roadmap, but not so many that fully incorporate Lean in a truly integrated Lean Sigma form. Figure 1.1 shows a robust version of a fully integrated approach put together over many years by the thought leaders at Sigma Breakthrough Technologies, Inc. (SBTI).[7] The roadmap follows the basic tried and tested DMAIC (Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, and Control) approach from Six Sigma, but with Lean flow tools as well as Six Sigma statistical tools threaded seamlessly together throughout. As proven across a diverse range of SBTI clients, the roadmap is equally at home in service industries, manufacturing industries of all types, and healthcare, including sharp-end hospital processes, even though at first glance some tools may lean toward only one of these. For example, despite being considered most at home in manufacturing, the best Pull Systems I've seen were for controlling replenishment in office supplies. Similarly, Workstation Design applies equally to a triage nurse as it does to an assembly worker.

Figure 1.1. Integrated Lean Sigma Roadmap © SBTI, 2003[8]

The roadmap is a long way removed from its Six Sigma predecessors and is structured into three layers:

This is done purposefully to ensure the problem-solving approach isn't just a list of tools in an order. It has meaning inherent to its structure. This is a crucial point to practitioners. Throughout this book, I'll explain not only which tool to use, but also why it is used, so that Belts move from blind tool use to truly thinking about what they are doing and focusing on the end goal of improving the process. The best Belts I've found were the most practical thinkers, not the theorists. This is a practical roadmap, and the user should try and focus on the underlying principle of "I'll apply the minimum practical sequence of tools to understand enough about my process to robustly make dramatic improvement for once and for all in my process." | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 138