11 - Systemic Hypertension

Editors: McPhee, Stephen J.; Papadakis, Maxine A.; Tierney, Lawrence M.

Title: Current Medical Diagnosis & Treatment, 46th Edition

Copyright 2007 McGraw-Hill

> Table of Contents > 14 - Alimentary Tract

function show_scrollbar() {}

14

Alimentary Tract

Kenneth R. McQuaid MD

Symptoms & Signs of Gastrointestinal Disease

Dyspepsia

Dyspepsia refers to acute, chronic, or recurrent pain or discomfort centered in the upper abdomen. The discomfort may be characterized by or associated with upper abdominal fullness, early satiety, burning, bloating, belching, nausea, retching, or vomiting. Heartburn (retrosternal burning) should be distinguished from dyspepsia. Patients with dyspepsia often have heartburn as an additional symptom. When heartburn is the dominant complaint, gastroesophageal reflux is nearly always present. Dyspepsia occurs in 25% of the adult population and accounts for 3% of general medical office visits.

Etiology

A. Food or Drug Intolerance

Acute, self-limited indigestion may be caused by overeating, eating too quickly, eating high-fat foods, eating during stressful situations, or drinking too much alcohol or coffee. Many medications cause dyspepsia, including aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), antibiotics (metronidazole, macrolides), various diabetes drugs (metformin, alpha-glucosidase inhibitors, amylin analogs, GLP-1 receptor antagonists), cholinesterase inhibitors (donepezil, rivastigmine), corticosteroids, digoxin, iron, and opioids.

B. Luminal Gastrointestinal Tract Dysfunction

Peptic ulcer disease is present in 5 15% of patients with dyspepsia. Gastroesophageal reflux disease is present in up to 20% of patients with dyspepsia, even without significant heartburn. Gastric cancer is identified in 1% but is rare in persons under age 45 years. Other causes include gastroparesis (especially in diabetes mellitus), lactose intolerance or malabsorptive conditions, and parasitic infection (Giardia, Strongyloides).

C. Helicobacter pylori Infection

Chronic gastric infection with H pylori as a cause of dyspepsia remains controversial. The prevalence of H pylori-associated chronic gastritis in patients with dyspepsia without peptic ulcer disease is 20 50%, the same as in the general population.

D. Pancreatic Disease

Pancreatic carcinoma, chronic pancreatitis.

E. Biliary Tract Disease

The abrupt onset of epigastric or right upper quadrant pain due to cholelithiasis or choledocholithiasis should be readily distinguished from dyspepsia.

F. Other Conditions

Diabetes, thyroid disease, renal insufficiency, myocardial ischemia, intra-abdominal malignancy, gastric volvulus or paraesophageal hernia, and pregnancy are sometimes accompanied by dyspepsia.

G. Functional Dyspepsia

This is the most common cause of chronic dyspepsia. Up to two-thirds of patients have no obvious organic cause for their symptoms after evaluation. Symptoms may arise from a complex interaction of increased visceral afferent sensitivity, gastric delayed emptying or impaired accommodation to food, or psychosocial stressors. Although benign, these symptoms may be chronic and difficult to treat.

Clinical Findings

A. Symptoms and Signs

Given the nonspecific nature of dyspeptic symptoms, the history has limited diagnostic utility. It should clarify the chronicity, location, and quality of the discomfort, its relationship to meals, and whether it is relieved by antacids. Concomitant weight loss, persistent vomiting, constant or severe pain, dysphagia, hematemesis, or melena warrants endoscopy or abdominal imaging. Potentially offending medications and excessive alcohol use should be identified and discontinued if possible. The patient's reason for seeking care should be determined. Recent changes in employment, marital discord, physical and sexual abuse, anxiety, depression, and fear of serious disease may all contribute to the development and reporting of symptoms. Patients with functional dyspepsia often are younger, report a variety of abdominal

P.549

and extragastrointestinal complaints, show signs of anxiety or depression, or have a history of use of psychotropic medications.

The symptom profile alone does not differentiate between functional dyspepsia and organic gastrointestinal disorders. Based on the clinical history alone, primary care physicians misdiagnose nearly half of patients with peptic ulcers or gastroesophageal reflux and have < 25% accuracy in diagnosing functional dyspepsia.

The physical examination is rarely helpful. Signs of serious organic disease such as weight loss, organomegaly, abdominal mass, or fecal occult blood are further evaluated. In patients over age 50 years, initial laboratory work should include a blood count, electrolytes, liver enzymes, calcium, and thyroid function tests.

B. Special Examinations

1. Upper endoscopy

Upper endoscopy is the study of choice to diagnose gastroduodenal ulcers, erosive esophagitis, and upper gastrointestinal malignancy. Upper gastrointestinal barium radiography is inferior to endoscopy for the evaluation of dyspepsia. Upper endoscopy is indicated to look for gastric cancer or other serious organic disease in all patients over age 55 years with new-onset dyspepsia and in all patients with alarm features such as weight loss, dysphagia, recurrent vomiting, evidence of bleeding, or anemia. It is also helpful for patients who are concerned about serious underlying disease. For patients born in regions in which there is a higher incidence of gastric cancer, an age threshold of 45 years may be appropriate.

2. Empiric management

In patients younger than 55 years with uncomplicated dyspepsia (in whom gastric cancer is rare), initial noninvasive management strategies should be pursued. In most clinical settings, a noninvasive test for H pylori (IgG serology, fecal antigen test, or urea breath test) should be performed first. Although serologic tests are inexpensive, performance characteristics are poor in low-prevalence populations. If test results are negative in a patient not taking NSAIDs, peptic ulcer disease is virtually excluded. Most of these H pylori-negative patients have functional dyspepsia or atypical gastroesophageal reflux disease and can be treated with an antisecretory agent (proton pump inhibitor) for 4 weeks. For patients who have symptom relapse after discontinuation of the proton pump inhibitor, intermittent or long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy may be considered.

For patients in whom test results are positive for H pylori, antibiotic therapy proves definitive for over 90% of peptic ulcers and may improve symptoms in a small subset (< 10%) of infected patients with functional dyspepsia. Patients with persistent dyspepsia after H pylori eradication can be given a trial of proton pump inhibitor therapy. In clinical settings in which the prevalence of H pylori infection in the population is low (< 10%), it may be more cost-effective to initially treat all young patients with uncomplicated dyspepsia with a 4-week trial of a proton pump inhibitor. Patients who have symptom relapse after discontinuation of the proton pump inhibitor should be tested for H pylori and treated if positive.

Endoscopic evaluation is warranted when symptoms fail to respond to initial empiric management strategies or frequent symptom relapse occurs after discontinuation of antisecretory therapy. Abdominal imaging (ultrasonography or CT scanning) is performed only when pancreatic or biliary tract disease is suspected. Gastric emptying studies are valuable only in patients with recurrent vomiting. Ambulatory esophageal pH testing may be of value when atypical gastroesophageal reflux is suspected.

Treatment of Functional Dyspepsia

Regardless of the initial strategy undertaken for patients with dyspepsia, a significant proportion will have persistent or recurrent symptoms requiring evaluation with endoscopy. Most patients will have no significant findings and will be given a diagnosis of functional dyspepsia.

A. General Measures

Most patients have mild, intermittent symptoms that respond to reassurance and lifestyle changes. Alcohol, caffeine, and fatty foods should be reduced or discontinued. A food diary, in which patients record their food intake, symptoms, and daily events, may reveal dietary or psychosocial precipitants of pain.

B. Pharmacologic Agents

Drugs have demonstrated limited efficacy in the treatment of functional dyspepsia. One-third of patients derive relief from placebo. Antisecretory therapy for 2 4 weeks with either H2-receptor antagonists (ranitidine or nizatidine, 150 mg twice daily; famotidine, 20 mg twice daily; or cimetidine, 400 800 mg twice daily) or proton pump inhibitors (omeprazole, esomeprazole, or rabeprazole 20 mg, lansoprazole 30 mg, or pantoprazole 40 mg) may benefit 10 15% of patients, particularly those with dyspepsia and heartburn ( reflux-like dyspepsia ). Superiority of proton pump inhibitors to H2-antagonists has not been established. Low doses of antidepressants (eg, desipramine or nortriptyline, 10 50 mg at bedtime) are believed to benefit some patients, possibly by moderating visceral afferent sensitivity. However, side effects are common and response is patient specific. Doses should be increased slowly. The prokinetic agent metoclopramide (5 10 mg three times daily) may improve symptoms, but improvement does not correlate with the presence or absence of gastric emptying delay. Long-term metoclopramide use is associated with a high incidence of neuropsychiatric side effects and cannot be recommended. Limited studies to date have not demonstrated efficacy for the prokinetic agent tegaserod.

C. Anti-H pylori Treatment

A meta-analysis has suggested that a small number of patients (< 10%) derive benefit from H pylori eradication therapy.

P.550

D. Alternative Therapies

Psychotherapy and hypnotherapy may be of benefit in selected motivated patients. Herbal therapies (peppermint, caraway) may offer benefit with little risk of adverse effects.

Ford AC et al: Helicobacter pylori test and treat or endoscopy for managing dyspepsia: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2005;128:1838.

Gupta S et al: Management of nonsteroidal, anti-inflammatory, drug-associated dyspepsia. Gastroenterology 2005;129:1711.

Talley NJ et al; American Gastroenterological Association: American Gastroenterological Association Medical Position Statement: Evaluation of dyspepsia. Gastroenterology 2005;129: 1753.

Talley NJ et al; Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology: Guidelines for the management of dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100:2324.

Timmons S et al: Functional dyspepsia: motor abnormalities, sensory dysfunction, and therapeutic options. Am J Gastroenterol 2004;99:739.

Nausea & Vomiting

Nausea is a vague, intensely disagreeable sensation of sickness or queasiness that may or may not be followed by vomiting and is distinguished from anorexia. Vomiting often follows, as does retching (spasmodic respiratory and abdominal movements). Vomiting should be distinguished from regurgitation, the effortless reflux of liquid or food stomach contents; and from rumination, the chewing and swallowing of food that is regurgitated volitionally after meals.

The medullary vomiting center (which contains histamine H1-receptors and muscarinic cholinergic receptors) may be stimulated by four different sources of afferent input: (1) Afferent vagal and splanchnic fibers from the gastrointestinal viscera are rich in serotonin 5-HT3 receptors; these may be stimulated by biliary or gastrointestinal distention, mucosal or peritoneal irritation, or infections. (2) Fibers of the vestibular system, which have high concentrations of histamine H1 and muscarinic cholinergic receptors. (3) Higher central nervous system centers; here, certain sights, smells, or emotional experiences may induce vomiting. For example, patients receiving chemotherapy may develop vomiting in anticipation of its administration. (4) The chemoreceptor trigger zone, located outside the blood-brain barrier in the area postrema of the medulla, which is rich in opioid, serotonin 5-HT3, neurokinin 1 (NK1) and dopamine D2 receptors. This region may be stimulated by drugs and chemotherapeutic agents, toxins, hypoxia, uremia, acidosis, and radiation therapy. Although the causes of vomiting are many, a simplified list is provided in Table 14-1.

Complications of vomiting include dehydration, hypokalemia, metabolic alkalosis, aspiration, rupture of the esophagus (Boerhaave's syndrome), and bleeding secondary to a mucosal tear at the gastroesophageal junction (Mallory-Weiss syndrome).

Table 14-1. Causes of nausea and vomiting. | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||

Clinical Findings

A. Symptoms and Signs

Acute symptoms without abdominal pain are typically caused by food poisoning, infectious gastroenteritis, drugs, or systemic illness. Inquiry should be made into recent changes in medications, diet, other intestinal symptoms, or similar illnesses in family members. The acute onset of severe pain and vomiting suggests peritoneal irritation, acute gastric or intestinal obstruction, or pancreaticobiliary disease. Examination may reveal fever, focal tenderness or rigidity, guarding, or rebound tenderness. Persistent vomiting suggests pregnancy, gastric outlet obstruction, gastroparesis, intestinal dysmotility, psychogenic disorders, and central nervous system or systemic disorders. Vomiting that occurs in the morning before breakfast is common with pregnancy, uremia, alcohol intake, and increased intracranial pressure. Vomiting immediately after meals strongly suggests bulimia or psychogenic causes. Vomiting of undigested food one to several hours after meals is characteristic of gastroparesis or a gastric outlet obstruction; physical examination may reveal a succussion splash. Patients with acute or chronic symptoms should be asked about neurologic symptoms that suggest a central nervous system cause such as headache, stiff neck, vertigo, and focal paresthesias or weakness.

B. Special Examinations

With vomiting that is severe or protracted, serum electrolytes should be obtained to look for hypokalemia, azotemia, or metabolic alkalosis resulting from loss of gastric contents. Flat and upright abdominal radiographs are obtained in patients with severe pain or suspicion of mechanical obstruction to look for free intraperitoneal air or dilated loops of small bowel. If mechanical small intestinal or gastric obstruction is thought likely, a nasogastric tube is placed for relief of symptoms. The cause of gastric outlet obstruction is best demonstrated by upper endoscopy, and the cause of small intestinal obstruction is best demonstrated with barium radiography or abdominal CT imaging. Gastroparesis is confirmed by nuclear scintigraphic studies or 13C-octanoic acid breath tests, which show delayed gastric emptying and either upper endoscopy or barium upper gastrointestinal series showing no evidence of mechanical gastric outlet obstruction. Abnormal liver function tests or elevated amylase or lipase suggest pancreaticobiliary disease, which may be investigated with an abdominal sonogram or CT scan. Central nervous system causes are best evaluated with either head CT or MRI.

Treatment

A. General Measures

Most causes of acute vomiting are mild, self-limited, and require no specific treatment. Patients should ingest

P.551

P.552

clear liquids (broths, tea, soups, carbonated beverages) and small quantities of dry foods (soda crackers). For more severe acute vomiting, hospitalization may be required. Patients unable to eat and losing gastric fluids may become dehydrated, resulting in hypokalemia with metabolic alkalosis. Intravenous 0.45% saline solution with 20 mEq/L of potassium chloride is given in most cases to maintain hydration. A nasogastric suction tube for gastric decompression improves patient comfort and permits monitoring of fluid loss.

B. Antiemetic Medications

Medications may be given either to prevent or to control vomiting (see above). Combinations of drugs from different classes may provide better control of symptoms with less toxicity in some patients. All of these medications should be avoided in pregnancy. (For dosages, see Table 14-2.)

1. Serotonin 5-HT3-receptor antagonists

Ondansetron, granisetron, dolasetron, and palonosetron are effective in preventing chemotherapy- and radiation-induced emesis when initiated prior to treatment. Single-dose administration schedules are as effective as multiple-dose regimens. Although serotonin antagonists are effective for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting, less expensive alternatives (eg, dexamethasone or droperidol) are equally effective.

2. Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids (eg, dexamathesone) have antiemetic properties, but the basis for these effects is unknown. These agents enhance the efficacy of serotonin receptor antagonsists for preventing acute and delayed nausea and vomiting in patients receiving moderately to highly emetogenic chemotherapy regimens. For the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting, corticosteroids, serotonin antagonists, and droperidol have efficacy; however, combinations of these agents have additive benefit.

3. Neurokinin receptor antagonists

Aprepitant is a highly selective antagonist for NK1-receptors in the area postrema. It is used in combination with corticosteroids and serotonin antagonists for the prevention of acute and delayed nausea and vomiting with highly emetogenic chemotherapy regimens. Combined therapy with aprepitant prevents acute emesis in 80 90% and delayed emesis in > 70% of patients treated with highly emetogenic regimens.

4. Dopamine antagonists

The phenothiazines, butyrophenones, and substituted benzamides have antiemetic properties that are due to dopaminergic blockade as well as to their sedative effects. High doses of these agents are associated with antidopaminergic side effects, including extrapyramidal reactions and depression. These agents are used in a variety of situations. Cases of QT prolongation leading to ventricular tachycardia (torsade de pointes) have been reported in several patients receiving droperidol, hence electrocardiographic monitoring is recommended before and after administration.

Table 14-2. Common antiemetic dosing regimens. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

5. Antihistamines and anticholinergics

These drugs (eg, meclizine, dimenhydrinate, transdermal scopolamine) may be valuable in the prevention of vomiting arising from stimulation of the labyrinth, ie, motion sickness, vertigo, and migraines. They may induce drowsiness.

6. Sedatives

Benzodiazepines are used in psychogenic and anticipatory vomiting.

7. Cannabinoids

Marijuana has been used widely as an appetite stimulant and antiemetic. Pure 9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) is the major active ingredient in marijuana and is available by prescription as

P.553

dronabinol. In doses of 5 15 mg/m2, oral dronabinol is effective in treating nausea associated with chemotherapy, but it is associated with central nervous system side effects in most patients.

Apfel CC et al: A factorial trial of six interventions in the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting. N Engl J Med 2004;350:2441.

Hasler WL et al: Nausea and vomiting. Gastroenterology 2003;125:1860.

Sharma R et al: Management of chemotherapy-induced nausea, vomiting, oral mucositis, and diarrhoea. Lancet Oncol 2005;6:93.

Tramer MR: Treatment of postoperative nausea and vomiting. BMJ 2003;327:762.

Hiccups (Singultus)

Though usually a benign and self-limited annoyance, hiccups may be persistent and a sign of serious underlying illness. In patients on mechanical ventilation, hiccups can trigger a full respiratory cycle and result in respiratory alkalosis.

Causes of benign, self-limited hiccups include gastric distention (carbonated beverages, air swallowing, overeating), sudden temperature changes (hot then cold liquids, hot then cold shower), alcohol ingestion, and states of heightened emotion (excitement, stress, laughing). There are over 100 causes of recurrent or persistent hiccups, grouped into the following categories:

Central nervous system: Neoplasms, infections, cerebrovascular accident, trauma.

Metabolic: Uremia, hypocapnia (hyperventilation).

Irritation of the vagus or phrenic nerve: (1) Head, neck: Foreign body in ear, goiter, neoplasms. (2) Thorax: Pneumonia, empyema, neoplasms, myocardial infarction, pericarditis, aneurysm, esophageal obstruction, reflux esophagitis. (3) Abdomen: Subphrenic abscess, hepatomegaly, hepatitis, cholecystitis, gastric distention, gastric neoplasm, pancreatitis, or pancreatic malignancy.

Surgical: General anesthesia, postoperative.

Psychogenic and idiopathic.

Clinical Findings

Evaluation of the patient with persistent hiccups should include a detailed neurologic examination, serum creatinine, liver chemistry tests, and a chest radiograph. When the cause remains unclear, CT of the head, chest, and abdomen, echocardiography, bronchoscopy, and upper endoscopy may help. On occasion, hiccups may be unilateral; chest fluoroscopy will make the diagnosis.

Treatment

A number of simple remedies may be helpful in patients with acute benign hiccups. (1) Irritation of the nasopharynx by tongue traction, lifting the uvula with a spoon, catheter stimulation of the nasopharynx, or eating 1 tsp of dry granulated sugar. (2) Interruption of the respiratory cycle by breath holding, Valsalva's maneuver, sneezing, gasping (fright stimulus), or rebreathing into a bag. (3) Stimulation of the vagus, carotid massage. (4) Irritation of the diaphragm by holding knees to chest or by continuous positive airway pressure during mechanical ventilation. (5) Relief of gastric distention by belching or insertion of a nasogastric tube.

A number of drugs have been promoted as being useful in the treatment of hiccups. Chlorpromazine, 25 50 mg orally or intramuscularly, is most commonly used. Other agents reported to be effective include anticonvulsants (phenytoin, carbamazepine), benzodiazepines (lorazepam, diazepam), metoclopramide, baclofen, gabapentin, and occasionally general anesthesia.

Krakauer EL et al: Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Weekly clinicopathological exercises. Case 6 2005. A 58-year-old man with esophageal cancer and nausea, vomiting, and intractable hiccups. N Engl J Med 2005;352:817.

Moretti R et al: Gabapentin as a drug therapy of intractable hiccup because of vascular lesion: a three-year follow up. Neurologist 2004;10:102.

Constipation

The first step in evaluating the patient is to determine what is meant by constipation. Patients may define constipation as infrequent stools (fewer than 3 in a week), hard stools, excessive straining, or a sense of incomplete evacuation. Table 14-3 summarizes the many causes of constipation, which are discussed below.

Common Identifiable Causes of Constipation

A. Poor Dietary and Behavioral Habits

The majority of constipated patients have mild symptoms that cannot be attributed to any structural abnormalities, intestinal motility disorders, or systemic disease. Dietary review will reveal that most of these patients do not consume adequate fiber and fluids. Ingestion of additional 10 12 g of fiber per day either by dietary changes or the addition of commercial fiber supplementation is often all that is needed. At least one or two glasses of fluid should be taken with meals. The elderly are predisposed because of poor eating habits, a variety of medications, decreased colonic motility and, in some cases, inability to sit on a toilet (bed-bound patients).

B. Structural Abnormalities

Constipation may be caused by colonic lesions, such as neoplasms and strictures, that obstruct fecal passage. Diagnostic studies to exclude such lesions are indicated in patients with a family history of colon cancer or inflammatory bowel disease; with alarm symptoms

P.554

or signs, such as hematochezia, weight loss, anemia, or positive fecal occult blood tests (FOBT); and in patients older than 45 50 years with new-onset constipation. Defecatory difficulties also can be due to a variety of anorectal outlet problems that impede or obstruct flow (perineal descent, rectal prolapse, rectocele), some of which may require surgery, and Hirschsprung's disease (usually suggested by lifelong constipation).

Table 14-3. Causes of constipation in adults. | ||

|---|---|---|

|

C. Systemic Diseases

Medical diseases can cause constipation due to neurologic gut dysfunction, myopathies, endocrine disorders, and electrolyte abnormalities such as hypercalcemia or hypokalemia.

D. Medications

Anticholinergic and opioid agents are common causes of constipation.

Causes of Severe or Refractory Constipation

Patients whose constipation cannot be attributed to the above causes and who do not respond to conservative dietary management present difficult management problems. Conceptually, these patients can be divided into three classes.

A. Slow Colonic Transit

Normal colonic transit time is approximately 35 hours; more than 72 hours is significantly abnormal. Slow colonic transit may be part of a more generalized gastrointestinal dysmotility syndrome but most commonly is idiopathic. Colonic inertia is more common in women, some of whom have a history of psychosocial problems or sexual abuse.

B. Pelvic Floor Dysfunction

With normal defecation, the anal sphincter and puborectalis muscle relaxes. Patients with pelvic floor dysfunction women more often than men have a paradoxical contraction of the anal sphincter and pelvic floor during attempted defecation that impedes the bowel movement. They may complain of excessive straining with a sense of incomplete evacuation, the need for digital pressure on the vagina or perineum, or the need for digital disimpaction.

C. Irritable Bowel Syndrome

Patients with primary complaints of abdominal pain, bloating, or a sense of incomplete evacuation may have irritable bowel syndrome. (See below.)

Evaluation

A. Initial Management

All patients should undergo a history and physical examination, including digital rectal examination and stool testing for occult blood. Digital examination should assess for anatomic abnormalities, such as anal stricture, rectocele, rectal prolapse, or perineal descent during straining. In otherwise healthy patients under age 50 without alarm symptoms or signs, it is reasonable to initiate a trial of empiric treatment. Further diagnostic tests should be performed in patients with any of the following: age 50 years or older, severe constipation, signs of an organic disorders, alarm symptoms (hematochezia, weight loss, positive FOBT), a family history of colon cancer or inflammatory bowel disease, and in patients whose symptoms have not responded to empiric management. Laboratory studies should include a complete blood count, serum electrolytes, serum calcium, serum glucose, and serum thyroid-stimulating

P.555

hormone (TSH). A colonoscopy or flexible sigmoidoscopy and barium enema should be obtained to exclude a neoplasm, stricture, or inflammatory bowel disease.

B. Second Level of Investigation

Patients with refractory constipation not responding to conservative measures may require further investigation by means of colonic transit and pelvic floor function studies in order to distinguish slow colonic transit from outlet disorders. Colon transit time is measured by performing an abdominal radiograph 120 hours after ingestion of 24 radio-opaque markers. Retention of > 20% of the markers indicates prolonged transit. Pelvic floor dysfunction and anorectal disorders are assessed with balloon expulsion testing, anal manometry, and defecography.

Standard Treatment of Chronic Constipation

A. Dietary Measures

Proper dietary fluid and fiber intake should be emphasized. Fiber may be given by means of dietary alterations or fiber supplements (Table 14-4). Increased dietary fiber may cause temporary distention or flatulence, which often diminishes over several days. Response to fiber therapy is not immediate, and increases in dosage should be made gradually over 7 10 days. Whereas fiber may benefit most patients, it normally does not benefit patients with severe colonic inertia or outlet disorders.

B. Stool Surfactant Agents

Docusate sodium, 50 200 mg/d, or mineral oil, 14 45 mL/d, may be given orally or rectally to promote softening of stools. Aspiration of mineral oil can cause lipoid pneumonia.

C. Osmotic Laxatives

These agents, used to soften stools, may be given alone or in combination with fiber supplements (Table 14-4). They are commonly used in older nonambulatory patients to prevent constipation and fecal impaction. They are safe and are titrated to a dose that results in soft to semiliquid stools. The less expensive saline laxatives should be tried first before using more expensive osmotic agents, such as nonabsorbable carbohydrates or polyethylene glycol solution.

1. Saline laxatives

Magnesium-containing saline laxatives (milk of magnesia, magnesium sulfate) are the most commonly used agents for the prevention and treatment of chronic constipation. These agents should not be given to patients with renal insufficiency. Sodium phosphate or magnesium citrate may be used for aggressive treatment of acute constipation or as a purgative prior to surgical, endoscopic, or radiographic procedures.

2. Nonabsorbable carbohydrates

Either sorbitol (70%) or lactulose, 15 30 mL once or twice daily, is efficacious for the prevention or treatment of chronic constipation. These malabsorbed sugars are often limited by their propensity to induce bloating, cramps, and flatulence.

3. Polyethylene glycol solution

Polyethylene glycol is a component of solutions traditionally used for colonic lavage prior to colonoscopy (CoLyte, GoLYTELY, NuLytely). Polyethylene glycol 3350 powder (Miralax) is available for the treatment of acute or chronic constipation. Seventeen grams of powder may be mixed in water or juice and taken once or twice daily.

D. Stimulant Agents

These agents stimulate fluid secretion and colonic contraction, resulting in a bowel movement within 6 12 hours after oral ingestion or 15 60 minutes after rectal administration. Common preparations include bisacodyl, senna, cascara, and castor oil (Table 14-4). Colchicine (0.6 mg) or misoprostol (200 400 mcg) two or three times daily may be helpful in some patients with refractory constipation. The prokinetic agent tegaserod (6 mg twice daily) is a 5-HT4-receptor agonist that is approved for the treatment of chronic constipation. In randomized trials of patients with chronic constipation (fewer than three spontaneous bowel movements per week), 40% of patients who received tegaserod experienced an increase in the number of spontaneous bowel movements compared with 25% of those who received placebo. At present, this drug should be reserved for patients who have suboptimal response or side effects with less expensive agents.

Treatment of Fecal Impaction

Severe impaction of stool in the rectal vault may result in obstruction to further fecal flow, leading to partial or complete large bowel obstruction. Predisposing factors include severe psychiatric disease, prolonged bed rest and debility, neurogenic disorders of the colon, and spinal cord disorders. Clinical presentation includes decreased appetite, nausea, and vomiting, and abdominal pain and distention. There may be paradoxical diarrhea as liquid stool leaks around the impacted feces. Firm feces are palpable on digital examination of the rectal vault. Initial treatment is directed at relieving the impaction with enemas (saline, mineral oil, or diatrizoate) or digital disruption of the impacted fecal material. Long-term care is directed at maintaining soft stools and regular bowel movements (as above).

Table 14-4. Pharmacologic management of constipation. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

American College of Gastroenterology Task Force: An evidence-based approach to the management of chronic constipation in North America. Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100 (Suppl 1):S1.

Cash BD et al: The role of serotonergic agents in the treatment of patients with primary constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2005;22:1047.

P.556

P.557

Muller-Lissner SA et al: Myths and misconceptions about chronic constipation. Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100:232.

Rao SS et al: Clinical utility of diagnostic tests for constipation in adults: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100: 1605.

Ramkumar D et al: Efficacy and safety of traditional medical therapies for chronic constipation: systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100:936.

Wald A: Severe constipation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2005; 3:432.

Gastrointestinal Gas

Belching

Belching (eructation) is the involuntary or voluntary release of gas from the stomach or esophagus. It occurs most frequently after meals, when gastric distention results in transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxation. Belching is a normal reflex and does not itself denote gastrointestinal dysfunction. Virtually all stomach gas comes from swallowed air. With each swallow, 2 5 mL of air is ingested, and excessive amounts may result in distention, flatulence, and abdominal pain. This may occur with rapid eating, gum chewing, smoking, and the ingestion of carbonated beverages. Chronic excessive belching is almost always caused by aerophagia, common in anxious individuals and institutionalized patients. Evaluation should be restricted to patients with other complaints such as dysphagia, heartburn, early satiety, or vomiting.

Once patients understand the relationship between aerophagia and belching, most can deal with the problem by behavioral modification. Physical defects that hamper normal swallowing (ill-fitting dentures, nasal obstruction) should be corrected. Antacids and simethicone are of no value.

Flatus

The rate and volume of expulsion of flatus is highly variable. Flatus is derived from two sources: swallowed air and bacterial fermentation of undigested carbohydrate. The majority of swallowed air not belched passes through the gut and leaves as flatus. Swallowed air may contribute up to 500 mL of flatus per day (primarily nitrogen). Bacterial fermentation of undigested carbohydrates leads to the additional production of gas, particularly H2, CO2, and methane. The majority of this fermentation takes place in the colon. Under normal circumstances, a small substrate of fermentable substances reaches the colon. These substances include fructose, lactose, sorbitol, trehalose (mushrooms), raffinose, and stachyose (legumes, cruciferous vegetables). Complex starches and fiber may also cause gas. Gas production may be increased with ingestion of these carbohydrates or with malabsorption.

Determining abnormal from normal amounts of flatus is difficult. An initial trial of a lactose-free diet is recommended. Common gas-producing foods should be reviewed and the patient given an elimination trial. These include beans of all kinds, peas, lentils, brussels sprouts, cabbage, parsnips, leeks, onions, beer, and coffee. Fructose intolerance may be more common than previously appreciated. Fructose is present not only in many fruits but is also used commonly as a sweetener or as fructose corn syrup in candy, fruit juices, and soda. Foul odor may be caused by garlic, onion, eggplant, mushrooms, and certain herbs and spices. For patients with persistent complaints, complex starches, and fiber may be eliminated, but such restrictive diets are unacceptable to most patients. Of refined flours, only rice flour is gas-free.

The nonprescription agent Beano ( -d-galactosidase enzyme) reduces gas caused by foods containing raffinose and stachyose, ie, cruciferous vegetables, legumes, nuts, and some cereals. Activated charcoal may afford relief. Simethicone is of no proved benefit.

Complaints of chronic abdominal distention or bloating are common. Some of these patients may produce excess gas. However, many patients have impaired small bowel gas propulsion or enhance visceral sensitivity to gas distention. Many of these patients have an underlying functional gastrointestinal disorder such as irritable bowel syndrome or functional dyspepsia. Reduction of dietary fat, which delays intestinal gas clearance, may be helpful.

Azpiroz F et al: Abdominal bloating. Gastroenterology 2005; 129:1060.

Chitkara DK et al: Aerophagia in adults: a comparison with functional dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2005;22:855.

Diarrhea

Diarrhea can range in severity from an acute self-limited episode to a severe, life-threatening illness. To properly evaluate the complaint, the physician must determine the patient's normal bowel pattern and the nature of the current symptoms.

Approximately 10 L of fluid enter the duodenum daily, of which all but 1.5 L are absorbed by the small intestine. The colon absorbs most of the remaining fluid, with < 200 mL lost in the stool. Although diarrhea sometimes is defined as a stool weight of more than 200 300 g/24 h, quantification of stool weight is necessary only in some patients with chronic diarrhea. In most cases, the physician's working definition of diarrhea is increased stool frequency (more than three bowel movements per day) or liquidity of feces.

The causes of diarrhea are myriad. In clinical practice, it is helpful to distinguish acute from chronic diarrhea, as the evaluation and treatment are entirely different (Tables 14-5 and 14-7).

Table 14-5. Causes of acute infectious diarrhea. | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1. Acute Diarrhea

Etiology & Clinical Findings

Diarrhea acute in onset and persisting for less than 2 weeks is most commonly caused by infectious agents,

P.558

bacterial toxins (either preformed or produced in the gut), or drugs. Community outbreaks (including nursing homes, schools, cruise ships) suggest a viral etiology or a common food source. Similar recent illnesses in family members suggest an infectious origin. Ingestion of improperly stored or prepared food implicates food poisoning. Day care attendance or exposure to unpurified water (camping, swimming) may result in infection with Giardia or Cryptosporidium. Large Cyclospora outbreaks have been traced to contaminated produce. Recent travel abroad suggests traveler's diarrhea (see Chapter 30). Antibiotic administration within the preceding several weeks increases the likelihood of Clostridium difficile colitis. Finally, risk factors for HIV infection or sexually transmitted diseases should be determined. (AIDS-associated diarrhea is discussed in Chapter 31; infectious proctitis is discussed in this chapter under Anorectal Disorders.) Persons engaging in anal intercourse or oral-anal sexual activities are at risk for a variety of infections that cause proctitis, including gonorrhea, syphilis, lymphogranuloma venereum, and herpes simplex.

The nature of the diarrhea helps distinguish among different infectious causes (Table 14-5).

A. Noninflammatory Diarrhea

Watery, nonbloody diarrhea associated with periumbilical cramps, bloating, nausea, or vomiting suggests a small bowel source caused by either a toxin-producing bacterium (enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli [ETEC], Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus cereus, Clostridium perfringens) or other agents (viruses, Giardia) that disrupt normal absorption and secretory process in the small intestine. Prominent vomiting suggests viral enteritis or S aureus food poisoning. Although typically mild, the diarrhea (which originates in the small intestine) can be voluminous and result in dehydration with hypokalemia and metabolic acidosis (eg, cholera). Because tissue invasion does not occur, fecal leukocytes are not present.

B. Inflammatory Diarrhea

The presence of fever and bloody diarrhea (dysentery) indicates colonic tissue damage caused by invasion (shigellosis, salmonellosis, Campylobacter or Yersinia infection, amebiasis) or a toxin (C difficile, E coli O157:H7). Because these organisms involve predominantly the colon, the diarrhea is small in volume (< 1 L/d) and associated with left lower quadrant cramps, urgency, and tenesmus. Fecal leukocytes or lactoferrin usually are present in infections with invasive organisms. E coli O157:H7 is a Shiga toxin-producing noninvasive organism most commonly acquired from contaminated meat that has resulted in several outbreaks of an acute, often severe hemorrhagic colitis. In immunocompromised and HIV-infected patients, cytomegalovirus (CMV) can cause intestinal ulceration with watery or bloody diarrhea.

Infectious dysentery must be distinguished from acute ulcerative colitis, which may also present acutely with fever, abdominal pain, and bloody diarrhea. Diarrhea that persists for more than 14 days is not attributable to bacterial pathogens (except for C difficile) and should be evaluated as chronic diarrhea.

Evaluation

In over 90% of patients with acute noninflammatory diarrhea, the illness is mild and self-limited, responding within 5 days to simple rehydration therapy or antidiarrheal agents; diagnostic investigation is unnecessary. The isolation rate of bacterial pathogens from stool cultures in patients with acute noninflammatory diarrhea is under 3%. Thus, the goal of initial evaluation is to distinguish patients with mild disease from those with more serious illness. If diarrhea worsens or persists for more than 7 days, stool should be sent for fecal leukocyte or lactoferrin determination, ovum and parasite evaluation, and bacterial culture.

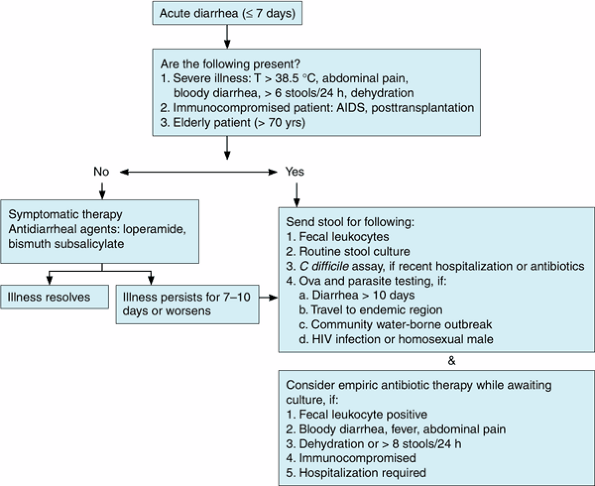

Prompt medical evaluation is indicated in the following situations (Figure 14-1): (1) Signs of inflammatory diarrhea manifested by any of the following: fever (> 38.5 C), bloody diarrhea, or abdominal pain. (2) The passage of six or more unformed stools in 24

P.559

hours. (3) Profuse watery diarrhea and dehydration. (4) Frail older patients. (5) Immunocompromised patients (AIDS, posttransplantation). (6) Nosocomial diarrhea (onset more than 3 days after hospitalization).

|

Figure 14-1. Evaluation of acute diarrhea. |

Physical examination pays note to the patient's level of hydration, mental status, and the presence of abdominal tenderness or peritonitis. Peritoneal findings may be present in infection with C difficile or enterohemorrhagic E coli. Hospitalization is required in patients with severe dehydration, toxicity, or marked abdominal pain. Stool specimens should be sent for examination for bacterial cultures (Table 14-6).

The rate of positive bacterial cultures in such patients is 60 75%. For bloody stools, the laboratory should be directed to perform serotyping for Shiga-producing E coli O157:H7. Special culture media are required for Yersinia, Vibrio, and Aeromonas. In patients who are hospitalized or who have a history of antibiotic exposure, a stool sample should be tested for C difficile toxin. In patients with diarrhea that persists for more than 10 days, who have a history of travel to areas where amebiasis is endemic, or who engage in oral-anal sexual practices, three stool examinations for ova and parasites should also be performed. The stool antigen detection tests for both Giardia and Entamoeba histolytica are more sensitive than stool microscopy for detection of these organisms. A serum antigen detection test for E histolytica is also available. Cyclospora and Cryptosporidium are detected by fecal acid-fast staining.

Treatment

A. Diet

Most mild diarrhea will not lead to dehydration provided the patient takes adequate oral fluids containing carbohydrates and electrolytes. Patients find it more comfortable to rest the bowel by avoiding high-fiber foods, fats, milk products, caffeine, and alcohol. Frequent feedings of tea, flat carbonated beverages, and soft, easily digested foods (eg, soups, crackers, bananas, applesauce, rice, toast) are encouraged.

Table 14-6. Fecal leukocytes in intestinal disorders. | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||

B. Rehydration

In more severe diarrhea, dehydration can occur quickly, especially in children, the frail, and the elderly. Oral rehydration with fluids containing glucose, Na+, K+, Cl-, and bicarbonate or citrate is preferred when feasible. A convenient mixture is 1/2 tsp salt (3.5 g),

P.560

1 tsp baking soda (2.5 g NaHCO3), 8 tsp sugar (40 g), and 8 oz orange juice (1.5 g KCl), diluted to 1 L with water. Alternatively, oral electrolyte solutions (eg, Pedialyte, Gatorade) are readily available. Fluids should be given at rates of 50 200 mL/kg/24 h depending on the hydration status. Intravenous fluids (lactated Ringer's injection) are preferred in patients with severe dehydration.

C. Antidiarrheal Agents

Antidiarrheal agents may be used safely in patients with mild to moderate diarrheal illnesses to improve patient comfort. Opioid agents help decrease the stool number and liquidity and control fecal urgency. However, they should not be used in patients with bloody diarrhea, high fever, or systemic toxicity and should be discontinued in patients whose diarrhea is worsening despite therapy. With these provisos, such drugs provide excellent symptomatic relief. Loperamide is preferred, in a dosage of 4 mg initially, followed by 2 mg after each loose stool (maximum: 16 mg/24 h).

Bismuth subsalicylate (Pepto-Bismol), two tablets or 30 mL four times daily, reduces symptoms in patients with traveler's diarrhea by virtue of its anti-inflammatory and antibacterial properties. It also reduces vomiting associated with viral enteritis. Anticholinergic agents (eg, diphenoxylate with atropine) are contraindicated in acute diarrhea because of the rare precipitation of toxic megacolon.

D. Antibiotic Therapy

1. Empiric treatment

Empiric antibiotic treatment of all patients with acute diarrhea is not indicated. Even patients with inflammatory diarrhea caused by invasive pathogens usually have symptoms that will resolve within several days without antimicrobials. Empiric treatment may be considered in patients with non-hospital-acquired diarrhea with moderate to severe fever, tenesmus, or bloody stools or the presence of fecal lactoferrin while the stool bacterial culture is incubating, provided that infection with E coli O157:H7 is not suspected. The drugs of choice for empiric treatment are the fluoroquinolones (eg, ciprofloxacin 500 mg, ofloxacin 400 mg, or norfloxacin 400 mg, twice daily, or levofloxacin 500 mg once daily) for 5 7 days. Alternatives include trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, 160/800 mg twice daily; or doxycycline, 100 mg twice daily. Macrolides and penicillins are no longer recommended because of widespread microbial resistance to these agents. Rifaximin, a nonabsorbed oral antibiotic, 200 mg three times daily for 3 days, is approved for empiric treatment of noninflammatory traveler's diarrhea (see Chapter 30).

2. Specific antimicrobial treatment

Antibiotics are not recommended in patients with nontyphoid Salmonella, Campylobacter, E coli O157:H7, Aeromonas, or Yersinia, except in severe disease, because they do not hasten recovery or reduce the period of fecal bacterial excretion. The infectious diarrheas for which treatment is recommended are shigellosis, cholera, extraintestinal salmonellosis, traveler's diarrhea, C difficile infection, giardiasis, and amebiasis. Therapy for traveler's diarrhea, infectious (sexually transmitted) proctitis, and AIDS-related diarrhea is presented in other chapters of this book.

Musher DM et al: Contagious acute gastrointestinal infections. N Engl J Med 2004;350:2417.

Thielman NM et al: Clinical practice. Acute infectious diarrhea. N Engl J Med 2004;350:38.

2. Chronic Diarrhea

Etiology

The causes of chronic diarrhea may be grouped into seven major pathophysiologic categories (Table 14-7).

Table 14-7. Causes of chronic diarrhea. | |

|---|---|

|

P.561

A. Osmotic Diarrheas

As stool leaves the colon, fecal osmolality is equal to the serum osmolality, ie, approximately 290 mosm/kg. Under normal circumstances, the major osmoles are Na+, K+, Cl-, and HCO3-. The stool osmolality may be estimated by multiplying the stool (Na+ + K+) 2. The osmotic gap is the difference between the measured osmolality of the stool (or serum) and the estimated stool osmolality and is normally less than 50 mosm/kg. An increased osmotic gap (> 125 mosm/kg) implies that the diarrhea is caused by ingestion or malabsorption of an osmotically active substance. The most common causes are disaccharidase deficiency (lactase deficiency), laxative abuse, and malabsorption syndromes (see below). Osmotic diarrheas resolve during fasting. Those caused by malabsorbed carbohydrates are characterized by abdominal distention, bloating, and flatulence due to increased colonic gas production.

Disaccharidase deficiencies are common and should be considered in all patients with chronic diarrhea. Lactase deficiency occurs in 75% of nonwhite adults and up to 25% of whites. It may also be acquired after an episode of viral gastroenteritis, medical illness, or gastrointestinal surgery. Sorbitol is commonly used as a sweetener in gums, candies, and some medications that may cause diarrhea in some patients. The diagnosis of sorbitol or lactose malabsorption may be established by an elimination trial for 2 3 weeks.

Ingestion of magnesium- or phosphate-containing compounds (laxatives, antacids) should be considered in enigmatic chronic diarrhea. Surreptitious use should be considered, especially in patients with a long history of undiagnosed medical ailments or employment in the medical field. The fat substitute olestra also causes diarrhea and cramps in occasional patients.

B. Secretory Conditions

Increased intestinal secretion or decreased absorption results in a high-volume watery diarrhea with a normal osmotic gap. There is little change in stool output during the fasting state, and dehydration and electrolyte imbalance may develop. Causes include endocrine tumors (stimulating intestinal or pancreatic secretion), bile salt malabsorption (stimulating colonic secretion), and laxative abuse.

C. Inflammatory Conditions

Diarrhea is present in most patients with inflammatory bowel disease (ulcerative colitis, Crohn's disease, microscopic colitis). A variety of other symptoms may be present, including abdominal pain, fever, weight

P.562

loss, and hematochezia. (See Inflammatory Bowel Disease, below.)

D. Malabsorptive Conditions

The major causes of malabsorption are small mucosal intestinal diseases, intestinal resections, lymphatic obstruction, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, and pancreatic insufficiency. Its characteristics are weight loss, osmotic diarrhea, steatorrhea, and nutritional deficiencies. Significant diarrhea in the absence of weight loss is not likely to be due to malabsorption. The physical and laboratory abnormalities related to deficiencies of vitamins or minerals are discussed in Chapter 29.

E. Motility Disorders

Abnormal intestinal motility secondary to systemic disorders or surgery may result in diarrhea due to rapid transit or to stasis of intestinal contents with bacterial overgrowth, resulting in malabsorption. Probably the most common cause of chronic diarrhea is irritable bowel syndrome (see Irritable Bowel Syndrome, below).

F. Chronic Infections

Chronic parasitic infections may cause diarrhea through a number of mechanisms. Pathogens most commonly associated with diarrhea include the protozoans Giardia, E histolytica, and Cyclospora as well as the intestinal nematodes. Bacterial infections with Aeromonas and Plesiomonas may uncommonly be a cause of chronic diarrhea.

Immunocompromised patients are susceptible to infectious organisms that can cause acute or chronic diarrhea (see Chapter 31), including Microsporida, Cryptosporidium, CMV, Isospora belli, Cyclospora, and Mycobacterium avium complex.

G. Factitious Diarrhea

Fifteen percent of patients have factitious diarrhea caused by surreptitious laxative abuse or dilution of stool.

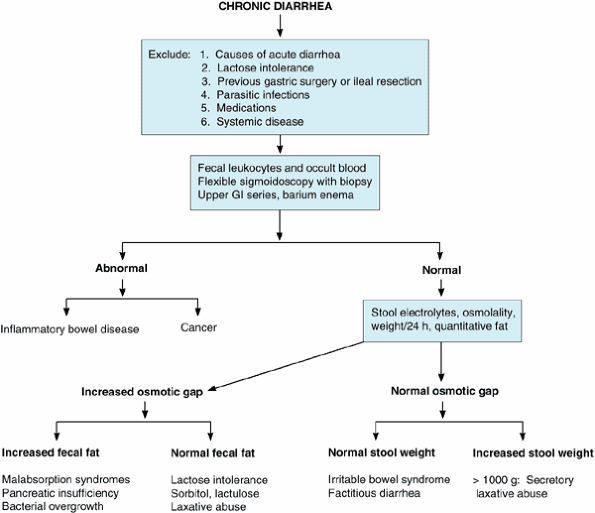

Evaluation

The history and physical examination commonly suggest the underlying pathophysiology that guides the subsequent diagnostic workup (Figure 14-2). Important tests are described here. AIDS-associated diarrhea is discussed in Chapter 31.

A. Stool Analysis

1. Twenty-four-hour stool collection for weight and quantitative fecal fat

A stool weight of more than 300 g/24 h confirms diarrhea. A weight > 500 g excludes irritable bowel syndrome, whereas a weight > 1000 1500 g suggests a secretory process. A fecal fat determination in excess of 10 g/24 h indicates a malabsorptive disorder. (See Celiac Sprue and specific tests for malabsorption, below.)

2. Stool osmolality

Stool osmolality less than serum osmolality implies that water or urine has been added to the specimen (factitious diarrhea). A stool pH < 5.6 is consistent with carbohydrate malabsorption.

3. Stool laxative screen

In cases of suspected laxative abuse, stool magnesium, phosphate, and sulfate levels may be measured. Phenolphthalein and bisacodyl can be analyzed in stool water, using chromatographic techniques. Anthraquinones and bisacodyl are sought for in the urine.

4. Fecal leukocytes

The presence of fecal leukocytes or lactoferrin implies inflammatory diarrhea.

5. Stool for ova and parasites

The presence of Giardia and E histolytica may be detected in wet mounts. However, fecal antigen detection tests for Giardia and E histolytica may be a more sensitive and specific method of detection. Cryptosporidium and Cyclospora are found with modified acid-fast staining.

B. Blood Tests

1. Routine laboratory tests

Complete blood count, serum electrolytes, liver function tests, calcium, phosphorus, albumin, TSH, -carotene, and prothrombin time may be of value. Anemia occurs in malabsorption syndromes (folate, iron deficiency [rare], or vitamin B12) as well as inflammatory conditions. Hypoalbuminemia is present in malabsorption, protein-losing enteropathies, and inflammatory diseases. Hyponatremia and nonanion gap metabolic acidosis occur in secretory diarrheas.

2. Other laboratory tests

In patients with suspected malabsorption, serologic testing for celiac sprue includes IgG and IgA antigliadin or tissue transglutaminase antibodies. Secretory diarrheas due to neuroendocrine tumors are rare. When this is suspected, serum vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) (VIPoma), calcitonin (medullary thyroid carcinoma), gastrin (Zollinger-Ellison syndrome), and glucagon determinations may be diagnostic. Urine should be sent for 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) (carcinoid), vanillylmandelic acid (VMA), metanephrine, and histamine determinations.

3. Endoscopic examination and mucosal biopsy

Either sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy with mucosal biopsy is helpful in the detection of inflammatory bowel disease (including microscopic colitis) and melanosis coli (indicative of chronic anthraquinone laxative use). Upper endoscopy with small bowel biopsy is performed when a small intestinal malabsorptive disorder is suspected (celiac sprue, Whipple's disease) and in patients with AIDS to document Cryptosporidium, Microsporida, and M avium-intracellulare infection. If bacterial overgrowth is suspected, the diagnosis is confirmed with noninvasive breath tests (D-[14C]xylose, glucose, or lactulose) or by obtaining an aspirate of small intestinal contents for quantitative aerobic and anaerobic bacterial culture.

|

Figure 14-2. Decision diagram for diagnosis of causes of chronic diarrhea. |

P.563

4. Other imaging studies

Calcification on a plain abdominal radiograph confirms a diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis, although abdominal CT and endoscopic ultrasonography are more sensitive for the diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis as well as pancreatic cancer. Small intestinal barium radiography is helpful in the diagnosis of Crohn's disease, small bowel lymphoma, carcinoid, and jejunal diverticula. Neuroendocrine tumors may be localized using somatostatin receptor scintigraphy.

Treatment

A number of antidiarrheal agents may be used in certain patients with chronic diarrheal conditions and are listed below. Opioids are safe in most patients with chronic, stable symptoms.

Loperamide: 4 mg initially, then 2 mg after each loose stool (maximum: 16 mg/d).

Diphenoxylate with atropine: One tablet three or four times daily as needed.

Codeine and deodorized tincture of opium: Because of potential habituation, these drugs are avoided except in cases of chronic, intractable diarrhea. Codeine may be given in a dosage of 15 60 mg every 4 hours; tincture of opium, 10 25 drops every 6 hours as needed.

Clonidine: 2-Adrenergic agonists inhibit intestinal electrolyte secretion. Clonidine, 0.1 0.6 mg twice daily, or a clonidine patch, 0.1 0.2 mg/d, may help in some patients with secretory diarrheas, diabetic diarrhea, or cryptosporidiosis.

Octreotide: This somatostatin analog stimulates intestinal fluid and electrolyte absorption and inhibits intestinal fluid secretion and the release of gastrointestinal peptides. It is given for secretory diarrheas due to neuroendocrine tumors (VIPomas, carcinoid) and in some cases of AIDS-related diarrhea. Effective doses range from 50 to 250 mcg subcutaneously three times daily.

Cholestyramine: This bile salt-binding resin may be useful in patients with bile salt-induced diarrhea

P.564

secondary to intestinal resection or ileal disease. A dosage of 4 g once to three times daily is recommended.

Camilleri M: Chronic diarrhea: a review on pathophysiology and management for the clinical gastroenterologist. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004;2:198.

Headstrom PD et al: Chronic diarrhea. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2005;3:734.

Schiller L: Chronic diarrhea. Gastroenterology 2004;127:287.

Thomas PD et al: Guidelines for the investigation of chronic diarrhea, 2nd edition. Gut 2003;52(Suppl 5):v1.

Gastrointestinal Bleeding

1. Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding

![]() Essentials of Diagnosis

Essentials of Diagnosis

Hematemesis (bright red blood or coffee grounds ).

Melena in most cases; hematochezia in massive upper gastrointestinal bleeds.

Volume status to determine severity of blood loss; hematocrit is a poor early indicator of blood loss.

Endoscopy diagnostic and may be therapeutic.

General Considerations

There are over 250,000 hospitalizations a year in the United States for acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding, with a mortality rate of 7 10%. Approximately half of patients are over 60 years of age, and in this age group the mortality rate is even higher. Patients seldom die of exsanguination but rather from complications of an underlying disease.

The most common presentation of upper gastrointestinal bleeding is hematemesis or melena. Hematemesis may be either bright red blood or brown coffee grounds material. Melena develops after as little as 50 100 mL of blood loss in the upper gastrointestinal tract, whereas hematochezia requires a loss of more than 1000 mL. Although hematochezia generally suggests a lower bleeding source (eg, colonic), upper gastrointestinal bleeding may present with hematochezia in 10% of cases.

Upper gastrointestinal bleeding is self-limited in 80% of patients; urgent medical therapy and endoscopic evaluation are obligatory in the rest. Patients with bleeding more than 48 hours prior to presentation have a low risk of recurrent bleeding.

Etiology

Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding may originate from a number of sources. These are listed in order of the frequency and discussed in detail below.

A. Peptic Ulcer Disease

Peptic ulcers account for half of major upper gastrointestinal bleeding with an overall acute mortality rate of 6 10%. However, in North America the incidence of bleeding from ulcers is declining, perhaps due to eradication of H pylori, use of safer NSAIDs, and prophylaxis with proton pump inhibitors in high-risk patients.

B. Portal Hypertension

Portal hypertension causes bleeding from varices (most commonly esophageal; rarely, gastric or duodenal) or portal hypertensive gastropathy. Acute bleeding develops in less than one-third of patients with portal hypertension and varices; however, these lesions account for 10 20% of significant gastrointestinal hemorrhages. If untreated, 50% of varices will rebleed during hospitalization. Due to improved care, the hospital mortality rate of has declined over the past 20 years from 40% to 15%. Nevertheless, a mortality rate of 60 80% is expected at 1 4 years due to recurrent bleeding or other complications of chronic liver disease.

C. Mallory-Weiss Tears

Lacerations of the gastroesophageal junction cause 5 10% of cases of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Many patients report a history of heavy alcohol use or retching. Less than 10% have continued or recurrent bleeding.

D. Vascular Anomalies

Vascular anomalies are found throughout the gastrointestinal tract and may be the source of chronic or acute gastrointestinal bleeding. They account for 7% of cases of acute upper tract bleeding. Vascular ectasias (angiodysplasias) have a bright red stellate appearance. They may be part of systemic conditions (hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, CREST syndrome) or may occur sporadically. There is an increased incidence in patients with chronic renal failure. Dieulafoy's lesion is an aberrant, large-caliber submucosal artery, most commonly in the proximal stomach that causes recurrent, intermittent bleeding.

E. Gastric Neoplasms

Gastric neoplasms result in 1% of upper gastrointestinal hemorrhages.

F. Erosive Gastritis

Because this process is superficial, it is a relatively unusual cause of severe gastrointestinal bleeding (< 5% of cases) and more commonly results in chronic blood loss. Gastric mucosal erosions are due to NSAIDs, alcohol, or severe medical or surgical illness (stress gastritis).

G. Erosive Esophagitis

Severe erosive esophagitis due to chronic gastroesophageal reflux may rarely cause significant upper gastrointestinal

P.565

bleeding, especially in patients who are bed bound long-term.

H. Others

An aortoenteric fistula complicates 2% of abdominal aortic grafts or can occur as the initial presentation of a previously untreated aneurysm. Usually located between the graft or aneurysm and the third portion of the duodenum, these fistulas characteristically present with a herald nonexsanguinating initial hemorrhage, with melena and hematemesis, or with chronic intermittent bleeding. The diagnosis may be suspected by upper endoscopy or abdominal CT. Surgery is mandatory to prevent exsanguinating hemorrhage. Unusual causes of upper gastrointestinal bleeding include hemobilia (from hepatic tumor, angioma, penetrating trauma), pancreatic malignancy, and pseudoaneurysm (hemosuccus pancreaticus).

Initial Evaluation & Management

A. Stabilization

The initial step is assessment of the hemodynamic status. A systolic blood pressure less than 100 mm Hg identifies a high-risk patient with severe acute bleeding. A heart rate over 100 beats/min with a systolic blood pressure over 100 mm Hg signifies moderate acute blood loss. A normal systolic blood pressure and heart rate suggest relatively minor hemorrhage. Postural hypotension and tachycardia are useful when present but may be due to causes other than blood loss. Because the hematocrit may take 24 72 hours to equilibrate with the extravascular fluid, it is not a reliable indicator of the severity of acute bleeding.

In patients with significant bleeding, two 18-gauge or larger intravenous lines should be started prior to further diagnostic tests. Blood is sent for complete blood count, prothrombin time with international normalized ratio (INR), serum creatinine, liver enzymes, and cross-matching for 2 4 units or more of packed red blood cells. In patients without hemodynamic compromise or overt active bleeding, aggressive fluid repletion can be delayed until the extent of the bleeding is further clarified. Patients with evidence of hemodynamic compromise are given 0.9% saline or lactated Ringer's injection and cross-matched blood. It is rarely necessary to administer type-specific or O-negative blood. Central venous pressure monitoring is desirable in some cases, but line placement should not interfere with rapid volume resuscitation.

A nasogastric tube should be placed in all patients with suspected active upper tract bleeding. The aspiration of red blood or coffee grounds confirms an upper gastrointestinal source of bleeding, though 10% of patients with confirmed upper tract sources of bleeding have nonbloody aspirates especially when bleeding originates in the duodenum. An aspirate of bright red blood indicates active bleeding and is associated with the highest risk of further bleeding, and complications, while a clear aspirate identifies patients at lower initial risk. Efforts to stop or slow bleeding by gastric lavage with large volumes of fluid are of no benefit and expose the patient to an increased risk of aspiration. Periodic reaspiration of the nasogastric tube serves as an indicator of ongoing bleeding or rebleeding.

B. Blood Replacement

The amount of fluid and blood products required is based on assessment of vital signs, evidence of active bleeding

P.566

from nasogastric aspirate, and laboratory tests. Sufficient packed red blood cells should be given to maintain a hematocrit of 25 30%. In the absence of continued bleeding, the hematocrit should rise 4% for each unit of transfused packed red cells. Transfusion of blood should not be withheld from patients with brisk active bleeding regardless of the hematocrit. It is desirable to transfuse blood in anticipation of the nadir hematocrit. In actively bleeding patients, platelets are transfused if the platelet count is under 50,000/mcL and considered if there is impaired platelet function due to aspirin use (regardless of the platelet count). Uremic patients (who also have dysfunctional platelets) with active bleeding are given three doses of desmopressin (DDAVP), 0.3 mcg/kg intravenously, at 12-hour intervals. Fresh frozen plasma is administered for actively bleeding patients with a coagulopathy and an INR > 1.5. In the face of massive bleeding, 1 unit of fresh frozen plasma should be given for each 5 units of packed red blood cells transfused.

C. Initial Triage

A preliminary assessment of risk based on several clinical factors aids in the resuscitation as well as the rational triage of the patient. Clinical predictors of increased risk of rebleeding and death include age over 65 years, comorbid illnesses, shock, and bright red blood in the nasogastric aspirate or on rectal examination.

1. Very low risk

Reliable patients without serious comorbid medical illnesses or advanced liver disease who have normal hemodynamics, no evidence of overt bleeding (hematemesis or melena) within 48 hours, a negative nasogastric lavage, and normal laboratory tests do not require hospital admission and can undergo further evaluation as outpatients as indicated.

2. High risk

Patients with active bleeding manifested by hematemesis or bright red blood on nasogastric aspirate, shock, persistent hemodynamic derangement despite fluid resuscitation, serious comorbid medical illness, or evidence of advanced liver disease require admission to an intensive care unit (ICU). Emergent endoscopy should be performed after adequate resuscitation, usually within 12 hours.

3. Low to moderate risk

All other patients are admitted to a step-down unit or medical ward after appropriate stabilization for further evaluation and treatment. Patients without evidence of active bleeding undergo nonemergent endoscopy usually within 12 24 hours. In some centers, these patients undergo urgent upper endoscopy to help decide appropriate triage. Based on the findings at endoscopy, patients deemed to be at low risk of rebleeding may be discharged and monitored as outpatients.

Subsequent Evaluation & Treatment

Specific treatment of the various causes of upper gastrointestinal bleeding is discussed elsewhere in this chapter. The following general comments apply to most patients with bleeding.

A. History and Physical Examination

The physician's impression of the bleeding source is correct in only 40% of cases. Signs of chronic liver disease implicate bleeding due to portal hypertension, but a different lesion is identified in 25% of patients with cirrhosis. A history of dyspepsia, NSAID use, or peptic ulcer disease suggests peptic ulcer. Acute bleeding preceded by heavy alcohol ingestion or retching suggests a Mallory-Weiss tear, though most of these patients have neither.

B. Upper Endoscopy

Virtually all patients with upper tract bleeding should undergo upper endoscopy. The benefits of endoscopy in this setting are threefold.

1. To identify the source of bleeding

The appropriate acute and long-term medical therapy is determined by the cause of bleeding. Patients with portal hypertension will be treated differently from those with ulcer disease. If surgery is required for uncontrolled bleeding, the source of bleeding as determined at endoscopy will determine the approach.

2. To determine the risk of rebleeding

Patients with a nonbleeding Mallory-Weiss tear, esophagitis, gastritis, and ulcers that have a clean, white base have a very low risk of rebleeding. It may be safe and cost-effective to discharge such patients from the emergency department or from the medical ward with subsequent outpatient follow-up. Patients with ulcers that are actively bleeding or have a visible vessel or who have variceal bleeding require closer observation in an ICU or step down unit.

3. To render endoscopic therapy

Hemostasis can be achieved in actively bleeding lesions with endoscopic modalities such as cautery, injection, or endoclips. About 90% of bleeding or nonbleeding varices can be effectively treated immediately with injection of a sclerosant or application of rubber bands to the varices. Similarly, 90% of bleeding ulcers, angiomas, or Mallory-Weiss tears can be controlled with either injection of epinephrine, direct cauterization of the vessel by a heater probe or multipolar electrocautery probe, or application of an endoclip. Certain nonbleeding lesions such ulcers with visible blood vessels, and angiomas are also treated with these therapies. Specific endoscopic therapy of varices, peptic ulcers, and Mallory-Weiss tears is dealt with elsewhere in this chapter.

C. Acute Pharmacologic Therapies

1. Acid inhibitory therapy

H2-receptor antagonists do not stop acute bleeding or reduce the incidence of rebleeding. Intravenous proton pump inhibitors (omeprazole, lansoprazole, or pantoprazole, 80 mg bolus, followed by 8 mg/h continuous infusion for 72 hours) reduce the risk of rebleeding in patients with peptic ulcers with high-risk features (active bleeding, visible vessel, or adherent clot) after endoscopic treatment. High doses of oral proton pump inhibitors (omeprazole 40 mg or lansoprazole 60 mg, twice daily for 5 days) may also be effective. Pending the results of endoscopic examination, it may be reasonable to initiate therapy with a high-dose proton pump inhibitor (intravenously or orally) in patients with suspected peptic ulcer bleeding.

2. Octreotide

Continuous intravenous infusion of octreotide (100 mcg bolus, followed by 50 100 mcg/h) reduces splanchnic blood flow and portal blood pressures and is effective in the initial control of bleeding related to portal hypertension. It is administered promptly to all patients with active upper gastrointestinal bleeding and evidence of liver disease or portal hypertension until the source of bleeding can be determined by endoscopy.

3. Vasoactive agents

Intravenous vasopressin is no longer used in the treatment of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. In countries where it is available, terlipressin may be preferred to octreotide for the treatment of bleeding related to portal hypertension because of its sustained reduction of portal and variceal pressures and its proven reduction in mortality.

D. Other Treatment

1. Intra-arterial embolization or vasopressin

Angiographic treatment is used rarely in patients with persistent bleeding from ulcers, angiomas, or Mallory-Weiss tears who have failed endoscopic therapy and are poor operative risks.

2. Transvenous intrahepatic portosystemic shunts (TIPS)

Placement of a wire stent from the hepatic vein through the liver to the portal vein provides effective decompression of the portal venous system and control of acute variceal bleeding. It is indicated in patients in whom endoscopic modalities have failed to control acute variceal bleeding.

Adler DG: ASGE Guideline: the role of endoscopy in acute non-variceal upper-GI hemorrhage. Gastrointest Endosc 2004; 60;497.

Bardou M et al: Meta-analysis: proton-pump inhibition in high-risk patients with acute peptic ulcer bleeding. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2005;21:677.

Barkun A et al: Consensus recommendations for managing patients with nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Ann Intern Med 2003;139:843.

P.567

Das A et al: Prediction of outcome of acute GI hemorrhage: a review of risk scores and predictive models. Gastrointest Endosc 2004;60:85.

Pavey DA: Endoscopic therapy for upper-GI vascular ectasias. Gastrointest Endosc 2004;59:233.

2. Acute Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding

![]() Essentials of Diagnosis

Essentials of Diagnosis

Hematochezia usually present.

Ten percent of cases of hematochezia due to upper gastrointestinal source.

Evaluation with colonoscopy in stable patients.

Massive active bleeding calls for evaluation with sigmoidoscopy, upper endoscopy, angiography, or nuclear bleeding scan.

General Considerations

Lower gastrointestinal bleeding is defined as that arising below the ligament of Treitz, ie, the small intestine or colon; however, over 95% of cases arise from the colon. The severity of lower gastrointestinal bleeding ranges from mild anorectal bleeding to massive, large-volume hematochezia. Bright red blood that drips into the bowl after a bowel movement or is mixed with solid brown stool signifies mild bleeding, usually from an anorectosigmoid source, and can be evaluated in the outpatient setting. Serious lower gastrointestinal bleeding is more common in older men. In patients hospitalized with gastrointestinal bleeding, lower tract bleeding is one-fourth as common as upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage and tends to have a more benign course. Patients hospitalized with lower gastrointestinal tract bleeding are less likely to present with shock or orthostasis (< 20%) or to require transfusions (< 40%). Spontaneous cessation of bleeding occurs in over 85% of cases, and hospital mortality is less than 3%.

Etiology

The cause of these lesions depends on both the age of the patient and the severity of the bleeding. In patients under 50 years of age, the most common causes are infectious colitis, anorectal disease, and inflammatory bowel disease. In older patients, significant hematochezia is most often seen with diverticulosis, vascular ectasias, malignancy, or ischemia. In 20% of acute bleeding episodes, no source of bleeding can be identified.

A. Diverticulosis

Hemorrhage occurs in 3 5% of all patients with diverticulosis and is the most common cause of major lower tract bleeding, accounting for 50% of cases. A significant percentage of cases are associated with the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents. Although diverticula are more prevalent on the left side of the colon, bleeding more commonly originates on the right side. Diverticular bleeding usually presents as acute, painless, large-volume maroon or bright red hematochezia in patients over age 50 years. More than 95% of cases require less than 4 units of blood transfusion. Bleeding subsides spontaneously in 80% but may recur in up to 25% of patients.

B. Vascular Ectasias

Vascular ectasias (or angiodysplasias) occur throughout the upper and lower intestinal tracts and cause painless bleeding ranging from melena or hematochezia to occult blood loss. They are responsible for 5 10% of cases of lower gastrointestinal bleeding, where they are most often seen in the cecum and ascending colon. They are flat, red lesions (2 10 mm) with ectatic peripheral vessels radiating from a central vessel, and are most common in patients over 70 years and in those with chronic renal failure. Bleeding in younger patients more commonly arises from the small intestine.