Learning File Management

| An original design goal of the first Macintosh was to make using a computer easy. The first Apple file system engineers worked to find techniques to allow more "human" file names, and built a file system that did not require file extensions for files to open properly. The Macintosh file system was based on the concept of a type and a creator. The type refers to the document type, such as PDF or JPEG, while the creator specifies the application used to create the document. Type and creator were used for opening files under the original Mac OS. As computers became more interconnected and the Internet developed, it became clear that users needed to easily transfer and use files across different operating systems. These files had to work smoothly across multiple platforms and application types. Corporations set up local area networks with a variety of servers, including file servers, which users of any platform could use for storing or sharing files. The Macintosh file system was a seamless client in multiplatform environments. File system design has evolved, from enabling end users to name and use files easily to incorporating dynamic search technologies and providing advanced file system features for modern needs. Modern users need access to file types used years ago on early computers, but must be able to efficiently manage and find specific files on large disks in a timely manner. Now you will learn about file management features in Mac OS X, and new features in Mac OS X 10.4. Examining File ForksIn early versions of the Macintosh operating system, Apple file system engineers devised a binary file format and a disk-based catalog to associate files with the applications that could open them. The disk-based catalog was called the desktop database. That binary file format is still supported in Mac OS X 10.4: on a Mac OS Standard or Mac OS Extended volume, each file can have two parts known as forksa data fork and a resource fork.

A data fork is similar to a file on any operating systemit contains a chunk of data. A resource fork historically was used to store additional information relevant to the file itself, such as a custom icon, or individual file preferences, or the last location of a palette. In Mac OS X, much of that information is stored within the data fork for the file. Data that is useful for the file system, such as details you see in the Info window, and the file type, are stored in the HFS catalog. The HFS catalog in Mac OS X is different from the old desktop database, but is just as essential in matching files with applications that can open them. Resource forks are useful to provide backward compatibility, but they do not move smoothly to other file systems. When you move these files to nonMacintosh file systems, the resource forks might be discarded, potentially stripping the file of important information. In today's computing environments, files move from platform to platform as email attachments or through file servers, which can introduce other complications. Traditionally, to preserve all of the file data, Mac OS files had to be encoded into a flat file format before transfer. BinHex was a common format (its name means "binary hexadecimal"), but it was not user-friendly at all. In Mac OS X, to ease cross-platform file transfer, more portable file formats have been developedone of the most useful is the package, discussed in the next section. UFS volumes handle forked files differently. UFS doesn't have a catalog to help with file and application matching. To accommodate that, the file manager service in Mac OS X creates a shadow file for every binary file on the UFS volume. To help the Macintosh work seamlessly with UNIX-formatted volumes, this shadow file, in a format called AppleDouble, contains three things:

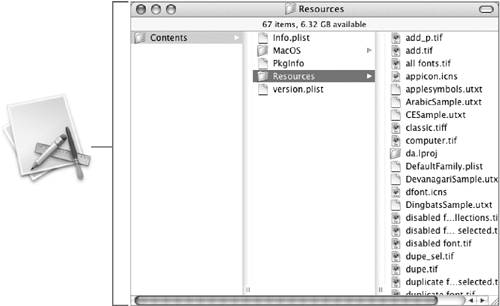

Opening PackagesMac OS X includes a mechanism to aid compatibility with the rest of the networked world, but at the same time provide a way to store resources and structured information in what appears to users to be a single file. The solution is called a package. The Finder presents and treats the package as a single file, although in reality it is a specially marked folder that can contain files and other folders. An application bundle in Mac OS X is one example of a package. Another example is a Keynote 2 file, which appears to the user as a single file, although it is really multiple files in a package.  The average user typically does not need to know about packages, just as the typical Mac user may never have been aware of resource forks. However, in the same way that a power user might have used ResEdit to edit the resource fork of a file in Mac OS 9, an administrator may need to view the contents of a package in Mac OS X. You can see the contents of an application package by Control-clicking its icon in column or icon view. You gain the real benefit of packages when you transfer packages to nonMacintosh file systems for storage, such as UFS or FAT, then copy those packages back to a Macintosh. The transfer to those file systems takes place as though the package is a folder, and the file is stored on the nonnative file system as a folder. When you copy that folder back to a Macintosh, the package flag ensures that the folder contents are copied like a folder, but the Mac user sees a package after the copy is complete. Using the Finder to Open FilesUser files (documents) are typically associated with particular applications, so you can simply double-click a file to open it with its associated application. In Mac OS X, applications keep track of the types of files they can read. When there might be several applications that can open a specific type of file, how does Mac OS X select the application to open when a document is double-clicked? To do this, Mac OS X has a LaunchServices process that keeps a record of which applications can be used to open various types of files. Two examples of this are as follows:

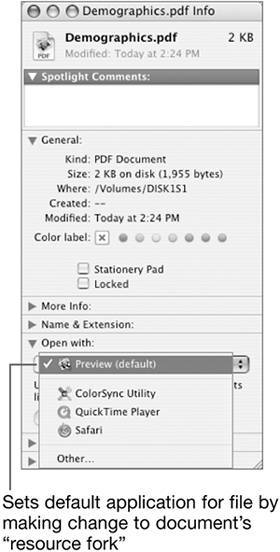

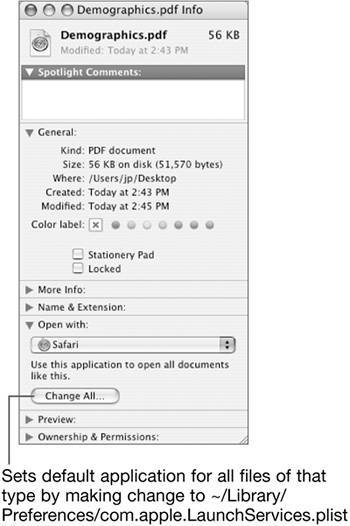

NOTE To see the default application for a given document type, Control-click the document in the Finder, then select Open With in the contextual menu that appears. Pressing the Option key with this menu open changes "Open With" to "Always Open With." As new applications are installed, the Installer updates the HFS catalog with new document types, and populates the LaunchServices database with new default bindings. This is how, after you install a third-party accounting application, Mac OS X is able to properly open the accounting application when you double-click its files. The LaunchServices databases are stored in /Library/Caches, named com.apple.LaunchServices.userID-based value.csstore. (The userID-based value will change from computer to computer.) There are databases for each user who has logged into the computer, because that file holds the "trusted bit" for applications. (The first time an application opens, an alert notifies the user, asking if it's OK to proceed. If so, the application's trusted bit is set and the alert won't appear again.) Each user also has a LaunchServices.plist file in his or her local ~/Library/Preferences folder that contains user-set bindings. User-set bindings override the default LaunchServices bindings, but only for that user. Overriding Default Preferences for Opening FilesMost documents are identified by type or extension. A file extension consists of a period (.) followed by several characters that identify the type of file. The Finder is set by default to display the full file name with extension, although you can change that setting for individual files in the Info window, and in many Save dialogs. A file works the same whether its extension is visible or hidden.

You can also change the application associated with a file using the Info window.

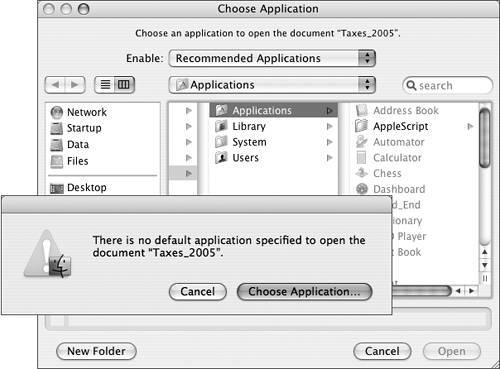

If you need to reset the system-wide bindings, discard the database (named com.apple.LaunchServices-userID-based value.csstore) from /Library/Caches and restart the computer. You can delete the user-set bindings file as well. Opening Documents That Do Not Have Default SettingsTraditionally, Mac OS applications have supported types and creators. However, on the Internet, and in other operating systems, file extensions are used to determine which applications open specific files. In most cases, a file extension is a multicharacter suffix preceded by a period, such as .pdf or .jpg. To be a good client and support both types of historical behavior, the Finder looks at file extensions as well as creator and type to determine how to open a file. If you double-click a file, the Finder first looks for a creator entry and if it finds one, uses it to determine which application opens the file. If there is no creator, it looks at the extension and finds an application that can open files with that extension. If there is no creator or extension, it looks at the file type and finds an application that can open that file type. If there is no creator, extension, or file type, the Finder will prompt you to choose an application that will become the default application to open the file.

To recap, this is the order of precedence the Finder uses when opening a new file that wasn't previously known:

NOTE This is the same mechanism used by some web browsers. Certain Helper applications can be configured to open certain document types, identified by the file extensions, such as .mov, .hqx, or .sit. Finding File Data and MetadataAlong with opening files, a common task when using any computer is locating the right files to open. In Mac OS X, a search can cover two types of file information: data and metadata.

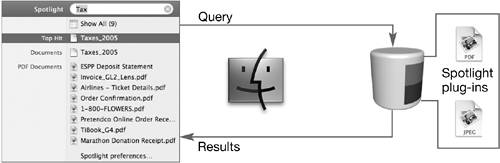

Both data and metadata are important when looking for files, and Mac OS X 10.4 includes new functionality for indexing and searching for data and metadata. Searching for Files Using SpotlightMac OS X 10.4 uses a new feature called Spotlight to search for data in files throughout your system. Spotlight creates and stores metadata indexes in an invisible folder named .Spotlight-V100 at the root level of each locally connected volume. Indexing takes place in the background while you are working.  On startup, Mac OS X 10.4 looks for index files stored on each connected volume. If it does not find them, it creates a new index. Any time you connect to a new volume locally, Spotlight indexes its content. The Mail application maintains its own content index at ~/Library/Mail/Envelope Index. If this index is removed, Mail will create a new index the next time it is launched. NOTE If you remove a metadata index, Spotlight rebuilds it the next time you restart. While Spotlight may seem to continue working properly, it will not be able to find or store any new data until you restart and Spotlight rebuilds the index files. File permissions are one of the metadata components that Spotlight indexes. So although all the content is indexed, Spotlight will filter its results to show only those files that the current user has permissions to access. Spotlight metadata for files in a FileVault-enabled user account is stored in ~/.Spotlight-V100. It is less secure to keep metadata outside the encrypted FileVault, so Spotlight automatically keeps the index for these files safely inside the encrypted home folder. To find and store metadata associated with the various file types on a typical Mac OS X system, Spotlight uses plugins to gather metadata and save it in a way that Mac OS X and Spotlight can search quickly. When you save a file, the plug-in examines its content and stores metadata about that content in the indexed database. This allows you to search for the metadata with Spotlight and quickly find the path of every file that matches your criteria. Many kinds of metadata, such as file size, creation date, and modification date, are common to all files. Mac OS X also includes plugins for metadata in common file formats used by specific applications. Applications that use the generic file formats can use the plugins supplied with Mac OS X. Applications with custom file formats will need to use their own plugins for Spotlight to index and search their metadata and contents. Mac OS X includes Spotlight plugins for several file formats and bundled applications. The plugins index most common Apple and third-party applications, such as Address Book, iCal, iTunes, Keynote, Mail, Microsoft Office, Pages, and Preview, as well as common generic formats such as PDF, RTF, and QuickTime. NOTE Plugins for common file formats and bundled applications are located in /System/Library/Spotlight. Although Mac OS X does not include AppleWorks, Keynote, Microsoft Office, or Pages as bundled applications, plugins for these applications are included and are located in /Library/Spotlight. Plugins created by developers other than Apple can be stored in multiple locations. They will take the form of a bundle or plug-in stored inside the application that references the data. Third party plugins can also be stored in ~/Library/Spotlight or /Library/Spotlight. NOTE Mac OS X does not index content or metadata on inserted optical media such as CDs or DVDs. If you burn a CD or DVD in Mac OS X, the burned disc does not contain a Spotlight-V100 folder and does not store content or metadata indexes. |

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 233