Consolidation and Cosourcing

While the management team worked on improving business-unit operations, they knew that pulling the company together at the center and driving down administrative costs were also urgent. Stewart put all the major cost elements of the business under one individual—Marco Trecroce. His title was group business transformation director, and his first task was consolidation. ‘‘I told Alan that if he wanted to transform the business quickly, he would need me to own line responsibility for a number of cost areas and let the rest of the business focus on revenue growth and margin improvement while I worked on the costs. That should be my job,’’ summarized Trecroce.

Trecroce identified and tracked 24 separate initiatives, including outsourcing ticket processing to Lufthansa, contracting with a company in India for IT legacy system maintenance, and outsourcing desktop management and mail distribution in the UK to a third company. One of the most significant activities was creating a shared services center for IT, finance, HR administration, and project management. Trecroce worked with consultants from Accenture, a major multinational consulting, technology, and outsourcing company, for several months to develop a solid business case for the initiative.

Cost reduction was important to Trecroce, but the shared services center had an even higher purpose. It would enable Thomas Cook to create a single administrative locus with a single set of information systems under the management of experts. This would deliver the culture change that Trecroce wanted and would enable Thomas Cook’s own management to concentrate on selling vacations. Ian Ailles, the company’s finance officer at the time, explained: ‘‘The finance consolidation was driven by geography. We had a finance team in Peterborough supporting the distribution business and one in London supporting the tour operator. We were closing that location. At the time we had four general ledger platforms and different charts of accounts. This was the ideal opportunity to get synergy and drive savings, and SAP was a key part of the answer.’’ Trecoce added: ‘‘To begin to work like one company, we had to concentrate on the back office first.’’

After crafting the business case for the shared-services center, the senior team considered, then rejected, the option of implementing it internally. ‘‘You use a partner to give you the momentum of change,’’ Ailles pointed out. ‘‘When you’re doing it yourself, no matter how hard you try, no matter how many new people you hire, you will get slowed down by the treacle of the organization. Marco and I are the chemists. We needed to use a partner as the catalyst.’’

After an initial review of the capabilities of four outsourcing providers, Trecroce shortlisted two large multinational companies and issued a formal request for proposal. He opened up intensive discussions with these organizations citing four clear and equally important criteria for vendor selection:

-

Speed to implementation

-

Skills and expertise, in streamlining back-office systems and processes and beyond

-

Ability to smooth the profit impact of the transformation

-

Contract flexibility

With Accenture’s fingerprints on the business case, however, the other shortlisted company had difficulty believing that the decision was not predetermined. ‘‘We were serious,’’ Stewart said. ‘‘We would have chosen them. But in the end, they could not understand the financial flexibility and the reinvestment approach that we needed. Accenture did.’’

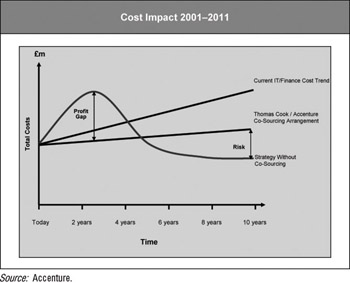

Thomas Cook chose Accenture as its partner in a ‘‘cosourcing arrangement’’ to build and operate the shared services center. They opted for cosourcing to emphasize that Thomas Cook would retain control over strategy, policy, investment, and procurement; and Accenture would focus on operational management. Stewart continued: ‘‘Cosourcing gives us the ability to generate savings over and above what we had expected, then choose whether to invest those savings through Accenture—like a bank account we can draw on—or to bank them ourselves through our P&L. This would be investment money that would not be in our budgets, but which we could control. It’s a good way of running a business—it gives us some operating slack.’’

In negotiating the contract details, Thomas Cook and Accenture first agreed on a level of work as the baseline. Both parties recognized that significant year-one investments would be required to achieve the anticipated savings. These investments were projected to pay off with step- change decreases in costs in years two and three. Thomas Cook pressed hard for Accenture to take on the risk of achieving the benefits. Trecroce argued:

At first, their concept of risk was pocket money. But if you only hand over the responsibility for running the back office to them, what is their incentive to get better? They have a high return on investment model, and they want more return, not less. So they want you to pay a high margin to them for providing a service, and that margin will not reduce in the future. So we had to develop a deal that transferred the responsibility for delivering benefits by making sure they have to take some of the financial pain if they don’t produce the benefits.

The contract incorporated a 1 million ($1.66 million) bonus if Accenture was able to reduce operating costs below the baseline by the end of year three.

Alex Christou, the partner responsible for Accenture’s European travel services practice and the Thomas Cook relationship, described the contract negotiation process as standing in the ‘‘middle of the hourglass.’’ He had to construct a business case that would both appeal to the client and work for Accenture. He recalled: ‘‘Given Accenture’s focus on EVA,[2] we had to find a way to reduce the huge capital needs of the deal without destroying its attractiveness to the client.’’ To leverage the financial strength of both partners, Christou proposed an arrangement that would make the much-needed profit improvement to Thomas Cook immediate and sustained. In exchange, Thomas Cook would provide investment capital for the transformation program. It would also continue to own the IT and physical assets that would support its parent company’s agenda to build purchasing power (see Exhibit 6.4). Christou explained:

Exhibit 6.4: Outsourcing financial model.

Accenture takes on all the legacy costs, and we are only able to re- cover the contract amount, as set out in the business case. That gives Accenture a first-year loss of, say, 30 percent of revenues. We have to draft Accenture experts into the center—that costs us anywhere between 10 and 30 percent of revenues. Then we have a cost for implementing the shared service center and SAP of 50 percent of year-one revenues. Before you know it, you’re up to 90 percent in the red in the first year of the deal.

In exploring options for the deal, it became apparent that Thomas Cook had ready access to capital just after the peak sales push for the summer vacation season. Christou continued: ‘‘Their access to capital was superior, so we suggested that they fund aspects of the transformation program.’’ Thomas Cook was able to capitalize many of these costs to soften the short-term impact on the P&L. The net effect was an immediate and sustainable profit improvement for Thomas Cook and an acceptable capital performance for Accenture. ‘‘This was one of several examples,’’ Christou recalled, ‘‘where open discussions helped us jointly shape the most commercially attractive deal for both parties.’’ It also illustrated the new degrees of freedom offered by a partnering model in contrast to a traditional consulting fee-for-service arrangement.

In October 2001, Thomas Cook eliminated 570 positions, implemented a pay freeze, and announced a 50 million loss for the fiscal year. It also announced the cosourcing agreement with Accenture. The next step was to get approval from the board of Thomas Cook AG.

Thomas Cook’s German parent questioned the merits of outsourcing. They were extremely concerned about a potential loss of control and with making a long-term commitment in a business environment that was rapidly changing. Stewart and Trecroce addressed the latter issue by including an official break point in the ten-year contract after three years. At that point, Thomas Cook could exit the deal: bring the operation back in-house, transfer it to another vendor, or consolidate it with the parent company’s other European operations. With this provision and Alan Stewart’s personal guarantee, the board ultimately agreed to co-source with Accenture in December 2001.

[2]Economic Value Added, a concept that measures company performance by the returns it is able to generate that exceed its weighted average cost of capital for the capital employed.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 135