13 - Sensory Impairment

Editors: Kane, Robert L.; Ouslander, Joseph G.; Abrass, Itamar B.

Title: Essentials of Clinical Geriatrics, 5th Edition

Copyright 2004 McGraw-Hill

> Table of Contents > Part III - General Management Strategies > Chapter 12 - Decreased Vitality

function show_scrollbar() {}

Chapter 12

Decreased Vitality

Among older adults, decreased vitality is a common complaint; it has a host of underlying causes. This chapter deals with metabolic factors that may lead to decreased energy in the older adults: endocrine disease, anemia, poor nutrition, lack of exercise, and infection.

ENDOCRINE DISEASE

![]() Carbohydrate Metabolism

Carbohydrate Metabolism

Of the elderly population, approximately 50 percent have glucose intolerance with normal fasting blood sugar levels. Although poor diet, obesity, and lack of exercise may account for some of these findings, aging itself is associated with deteriorating glucose tolerance. Most data suggest a change in peripheral glucose utilization as the major factor in this phenomenon, although beta-cell dysfunction and decreased insulin secretion are also contributing factors. Glucose intolerance should not be diagnosed as diabetes mellitus. However, such individuals are at increased risk of developing diabetes mellitus. Lifestyle-modification, including weight loss and exercise, prevents or forestalls the development of type 2 diabetes in individuals with glucose intolerance (Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group, 2002). Both the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and the American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommend these interventions for patients at risk for diabetes (US Preventive Services Task Force, 2003).

By the age of 75 years, approximately 20 percent of the population has developed diabetes mellitus (Meneilly and Tessier, 2001). At least half of these patients are unaware that they have the disease. The USPSTF concludes that the evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against routinely screening asymptomatic adults for type 2 diabetes, except that those with hypertension or hyperlipidemia should be screened as an approach to reducing cardiovascular risk. The ADA recommends that screening begin at age 45 years at 3-year intervals, but at shorter intervals in

P.306

high-risk patients. The diagnosis of diabetes should be made on the basis of a fasting plasma glucose of 126 mg/dL or greater on at least two occasions.

The therapeutic goal for most older diabetic patients is the same as that in younger patients: normal fasting plasma glucose without hypoglycemia. However, in those with short life expectancies, the therapeutic goal may be modified to eliminate symptoms associated with hyperglycemia. This can be accomplished by lowering the blood sugar to levels that avoid glycosuria. The age at which tight control is no longer indicated has not been defined; however, studies that demonstrated benefit of tight control were 4 to 6 years in duration.

Several groups of oral hypoglycemic agents, each with a different mechanism of action, are now available. Sulfonylureas act primarily by increasing beta-cell insulin secretion. They increase circulating insulin levels and are frequently associated with weight gain. Although package inserts carry a warning on the increased risk of cardiovascular disease, the UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group reported no adverse cardiovascular outcomes in sulfonylureas treated patients (UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group, 1998a). Acarbose reduces postprandial plasma glucose by inhibiting small intestine brush-border -glucosidases. It has a small effect on metabolic control and causes frequent gastrointestinal distress with bloating and flatulence. Metformin, a biguanide, exerts its major metabolic effect by inhibiting hepatic glucose production. It leads to significant improvement in glucose control when used alone or in combination with a sulfonylurea (Inzucchi et al., 1998). Unlike sulfonylureas, which often lead to weight gain, metformin therapy is associated with weight loss, a benefit to most type 2 diabetic patients. Weight should be monitored closely in thin diabetic patients.

A serious side effect of metformin is lactic acidosis. It should not be used in patients with renal insufficiency or congestive heart failure. In patients 80 years old or older, creatinine clearance should be measured before therapy is initiated. Metformin should be discontinued during illnesses associated with volume depletion and prior to surgery. Thiazolidinediones lower blood sugar by improving target-cell insulin sensitivity. Besides the potential for hepatic toxicity, which requires frequent liver function testing, thiazolidinedione therapy may be associated with marked weight gain. Fluid retention occurs more frequently in combination with insulin and in congestive heart failure, making these conditions contraindications for the use of these agents. Table 12-1 presents a step-care approach to the treatment of type 2 diabetes.

TABLE 12-1 STEP-CARE APPROACH TO THE TREATMENT OF TYPE 2 DIABETES | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||

Because of the results of the UKPDS study, close control of blood glucose in type 2 diabetes is now in vogue. Intensive blood-glucose control with sulfonylureas or insulin decreased the risk of microvascular complications, but not macrovascular disease. Intensive treatment did increase the risk of hypoglycemia. Intensive blood-glucose control with metformin in overweight patients decreased the risk of both microvascular and macrovascular complications, and was associated with less weight gain and fewer hypoglycemic attacks

P.307

P.308

than insulin and sulfonylureas (UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group, 1998b). Metformin is recommended as the first-line pharmacological therapy in overweight patients. It is important to observe patients closely for hypoglycemic reactions and their ability to respond to this stress as any of these regimens is prescribed. Although each agent is effective as monotherapy, the majority of patients need multiple therapies to attain glycemic target levels in the longer term (Turner et al., 1999).

Because most patients with adult-onset diabetes are obese, weight reduction should be attempted, although only approximately 10 percent will maintain a prolonged weight loss. Dietary fats should be reduced. Aerobic exercise is of benefit in both delaying the onset of type 2 diabetes mellitus and in improving insulin resistance in individuals with established disease.

Other atherosclerotic risk factors such as smoking, dyslipidemia, and hypertension should be eliminated or treated. Tight blood pressure control reduces both micro- and macrovascular complications in type 2 diabetes (UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group, 1998c). A meta-analysis of cholesterol lowering and blood pressure lowering trials demonstrated large, significant effects on reducing macrovascular disease in type 2 diabetes (Huang et al., 2001). The goal blood pressure for patients with diabetes is 130/85 mmHg or lower. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs) attenuate progression of nephropathy in both type 1 and type 2 diabetic patients with hypertension and in normotensives with microalbuminuria. They also attenuate decline in renal function in normotensive, normoalbuminuric type 2 diabetic patients (Ravid et al., 1998). The antihypertensive regimen of diabetics should include an ACE inhibitor or ARB, and such therapy should be initiated in normotensive albuminuric patients.

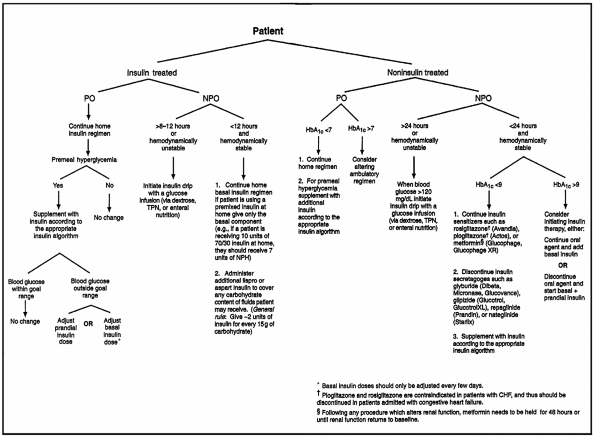

The goals for glycemic control are less-well established for hospitalized than for ambulatory patients. However, data suggest that maintaining blood glucose at 80 to 110 mg/dL in critically ill patients reduces mortality, and hyperglycemia adversely effects wound healing and increases the risk for infection. Although sliding scale insulin regimens are frequently used in hospitalized patients with diabetes, it is the opinion of the authors that they should not be used. The University of Washington has developed an algorithm to replace sliding scale insulin orders (Fig. 12-1).

|

FIGURE 12-1 Flow diagram for treatment of hospitalized (non-intensive care unit) protamine Hagedorn (insulin); NPO = nothing by mouth; PO = by mouth; TPN = total patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. CHF = congestive heart failure; NPH = neutral parenteral nutrition. (From Ku, 2002.) |

Older adults have an increased incidence of hyperosmolar nonketotic (HNK) coma. Characteristic symptoms and signs help the physician distinguish this syndrome from diabetic ketoacidotic (DKA) coma. Table 12-2 compares HNK and DKA. Whereas DKA frequently develops over hours, HNK typically develops over days to weeks. Focal or generalized seizures are common in HNK and unusual in uncomplicated DKA. The fluid deficit is greater in HNK, thus leading to a higher serum sodium and more marked rise in blood urea nitrogen. Therapy in HNK must therefore address the volume and hyperosmolar state of the patient. Because these patients may be quite sensitive to insulin, lowering of glucose

P.309

should be done cautiously. Volume replacement should be initiated with normal saline. This therapy alone may reduce blood glucose levels, as renal perfusion is enhanced and glucose is lost in the urine. If, after 1 hour of volume repletion, blood glucose levels are not reduced, a bolus of 20 U of regular insulin should be administered intravenously. If glucose levels do not respond, an insulin drip may be started. Such an approach should allow repletion of volume without lowering serum osmolarity too rapidly.

TABLE 12-2 HYPEROSMOLAR NONKETOTIC (HNK) COMA AND DIABETIC KETOACIDOSIS (DKA) | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||

![]() Thyroid

Thyroid

Although thyroid function is generally normal in aging, the physician should be aware of the norms for thyroid function tests for this age group (Table 12-3). The majority of data indicate that T4 levels are normal. T3 levels may be lower in healthy older people when compared to younger individuals, but are still in the normal range. It has been suggested that the lower T3 levels reported in several studies are caused by undiagnosed illness and the low-T3 syndrome described below. Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) levels are also normal, while the TSH response to thyroid-releasing hormone (TRH) is decreased in males and normal in females. Thus, the TRH test is less valuable in older males. Metabolic clearance of thyroid hormones is decreased in aging. With intact feedback loops, normal thyroid function is maintained despite this change. However, with exogenous replacement of thyroid hormone, such regulatory mechanisms are not maintained; thyroid replacement doses in older adults should be lower to take into account the lower metabolic clearance. Laboratory evaluation tests most useful in thyroid disease are summarized in Table 12-4.

TABLE 12-3 THYROID FUNCTION IN THE NORMAL ELDERLY | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||

TABLE 12-4 LABORATORY EVALUATION OF THYROID DISEASE IN THE ELDERLY | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Hypothyroidism

Hypothyroidism is primarily a disease of those age 50 to 70 years. Goiter is rarely seen with hypothyroidism in the elderly except when it is iodide-induced. Diagnosis is usually made by a low free T4 and an elevated TSH. Because total T4 levels may be depressed in seriously ill patients, diagnosis of hypothyroidism should not be made on the basis of low T4 levels alone. Table 12-5 lists laboratory characteristics of the low-T4 syndrome associated with nonthyroidal illness. Not all free-T4 methods distinguish the low-T4 syndrome from hypothyroidism; physicians should be aware of the type of determination and interpretation used in their laboratory. Because the T3 level may be in the normal range in hypothyroidism, this is not a helpful test. The low T3 level associated with a host of acute and chronic nonthyroidal illnesses also contributes to the poor specificity of this test in hypothyroidism. Approximately 75 percent of circulating T3 is derived from peripheral conversion from T4. The enzymes that convert T4 to T3 or reverse T3 are under metabolic control. During illness, more T4 is converted to reverse T3, leading to the characteristic laboratory findings of the low-T3 syndrome.

TABLE 12-5 THYROID-FUNCTION TESTS IN NONTHYROIDAL ILLNESS | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

P.310

P.311

P.312

The radioactive iodine uptake is also not helpful because normal values are so low that they overlap with hypothyroidism. The TRH stimulation test can be used in females, but decreased responsiveness to TRH in older males does not allow this test to distinguish normal from pathological states. In males, a TSH stimulation test may help to confirm the presence of hypothyroidism.

Hypothyroidism may be accompanied by other laboratory abnormalities. Creatine phosphokinase (CPK) levels, including CPK hypothyroidism, may be elevated. A normocytic, normochromic anemia, which responds to thyroid hormone replacement, may be present. There is an increased incidence of pernicious anemia in hypothyroidism, but the microcytic anemia of iron deficiency remains the commonest anemia associated with hypothyroidism.

The symptoms and signs of hypothyroidism may be overlooked when such complaints as fatigue, memory loss, and decreased hearing are ascribed to aging without further investigation. The prevalence of undiagnosed hypothyroidism in healthy

P.313

older people has varied from 0.5 to 2 percent in multiple studies; consequently, a general screening program is not cost-effective. The prevalence among older adults who are ill, however, is sufficient to support screening for hypothyroidism in this population, comprising individuals who have already presented themselves for care.

Therapy for hypothyroidism should be started at 0.025 to 0.05 mg of L-levothyroxine per day and increased by the same dose at 1- to 3-week intervals.

P.314

The decreased metabolic clearance rate of thyroid hormone in aging may lead to a lower maintenance dose of T4. The physician should monitor heart rate response and symptoms of angina and, in the laboratory, the TSH level. When indicated for symptomatic cardiovascular disease, a beta blocker may be added to the T4 regimen. In patients with coronary artery disease, therapy can be initiated with triiodothyronine 5 g/d and increased by 5 g at weekly intervals to a level of 25 g/d, at which time the patient can be converted to T4 therapy. Because T3 has a shorter half-life than T4, symptoms will remit more rapidly after discontinuance of therapy if the patient develops cardiovascular complications. A beta blocker can also be added to the T3 regimen.

Subclinical Hypothyroidism

Subclinical hypothyroidism is characterized by increased serum TSH concentrations with normal free T4 and free T3 levels. It occurs in 10 to 15 percent of the general population. The presentation is nonspecific and symptoms are usually subtle. In a prospective follow-up study, based on the initial TSH level (4 to 6/>6 to 12/>12) the incidence of overt hypothyroidism after 10 years was 0 percent, 42.8 percent, and 76.9 percent, respectively (Huber et al., 2002). The incidence of overt disease was increased in those with positive microsomal antibodies. Subclinical hypothyroidism is an independent risk factor for atherosclerosis and myocardial infarction (Hak et al., 2000), and is associated with left ventricular diastolic dysfunction that is improved with T4 therapy (Biondi et al., 1999). The decision to treat patients remains controversial. However, an algorithm for the management of subclinical hypothyroidism has been proposed (Fig. 12-2).

|

FIGURE 12-2 An algorithm for the management of subclinical hypothyroidism. LDL = low-density lipoprotein. (From Cooper, 2001.) |

Myxedema Coma

Most patients with myxedema coma are older than age 60 (Table 12-6). In approximately 50 percent of the cases, the coma is induced in the hospital by treating hypothyroid patients with hypnotics. A neck scar, from previous thyroid surgery, is a clue to the cause of coma. Because patients with this disorder die of respiratory failure, hypercapnia requires prompt attention. These patients should be treated in an intensive care setting, with intubation and respiratory assistance instituted at the first sign of respiratory failure. The cerebrospinal fluid protein level is often over 100 mg/dL and should not in itself be used as an indicator of other central nervous system pathology. Therapy includes a large initial dose (200 to 300 g) of T4 intravenously. Although studies have not been done to demonstrate the efficacy of glucocorticoids in this syndrome, it is generally recommended that these patients receive 50 mg of hydrocortisone every 6 hours for the first 1 or 2 days. Patients with concomitant adrenal insufficiency will require continued steroid therapy.

TABLE 12-6 MYXEDEMA COMA | |

|---|---|

|

Hyperthyroidism

Approximately 20 percent of hyperthyroid patients are older adults; 75 percent have classic signs and symptoms. Ophthalmopathy is infrequent. Approximately one-third have no goiter. Toxic multinodular goiter is more frequent than in the young. Severe nonthyroidal disease may disguise thyrotoxicosis

P.315

P.316

(apathetic hyperthyroidism). Congestive heart failure, stroke, and infection are common disorders associated with masked hyperthyroidism. There should be a high threshold of suspicion for hyperthyroidism in older adults. Unexplained heart failure or tachyarrhythmia, recent onset of a psychiatric disorder, or profound myopathy should raise questions about masked hyperthyroidism. The triad of weight loss, anorexia, and constipation, which may raise the possibility of neoplastic disease, occurs in 15 percent of older thyrotoxic patients. Diagnosis is made by T4, T3, and/or radioactive iodine uptake (see Table 12-4). The ultrasensitive TSH assays can differentiate hyperthyroidism from normal. In the absence of acute nonthyroidal disease, this test alone may confirm the clinical diagnosis of hyperthyroidism. In the presence of acute illness, concomitant determination of TSH and free T4 may be more appropriate. A T3 suppression test should not be done in older adults because of the risk of angina or myocardial infarction.

Therapy is usually by radioactive iodine ablation. Often patients are first treated with antithyroid medications to control hyperthyroidism and deplete the thyroid gland of hormone prior to the radioactive iodine treatment. Surgery is reserved for patients with thyroid glands that are causing local obstructive symptoms.

Severe thyrotoxicosis is treated with antithyroid drugs (preferably propylthiouracil because it blocks conversion of T4 to T3) to inhibit new hormone synthesis, iodides to block thyroid hormone secretion, and beta blockers to decrease the peripheral manifestations of thyroid hormone action. In older adults with underlying cardiac disease, beta-blocker therapy may be a problem; thus the cardiovascular response must be closely monitored. In patients allergic to antithyroid medications or where beta blockers are contraindicated, calcium ipodate (Oragrafin), 3 g every 3 days, can be used because it inhibits peripheral conversion of T4 to T3. Dexamethasone 2 mg every 6 hours inhibits peripheral conversion of T4 to T3 and may be added to any of the above regimens.

Subclinical Hyperthyroidism

Subclinical hyperthyroidism is defined as a combination of undetectable serum TSH and normal serum T3 and T4. Subclinical hyperthyroidism caused by multinodular goiter often progresses to overt hyperthyroidism, and ablative therapy with iodine-131 is usually recommended (Toft, 2001). In older patients with atrial fibrillation or osteoporosis that may be related to the mild excess of thyroid hormone, ablative therapy is also the best initial option. In patients with subtle, nonspecific symptoms in the absence of a multi-nodular goiter, an antithyroidal medication should be tried for a 6-month period. If symptoms improve, ablative therapy should be considered.

![]() Hyperparathyroidism

Hyperparathyroidism

One-third of patients with hyperparathyroidism are older than age 60. Symptoms are the same in older adults as in those who are younger, but may be overlooked.

P.317

Bone demineralization, weakness, and joint complaints may be ascribed to aging when they may actually indicate parathyroid disease. Parathyroidectomy should generally be recommended for patients with a secure diagnosis of primary hyperparathyroidism, even in the absence of classical symptoms (Silverberg et al., 1999).

Table 12-7 contrasts some of the basic patterns of the common laboratory tests in hyperparathyroidism with those of other metabolic bone diseases that are common in older adults.

TABLE 12-7 LABORATORY FINDINGS IN METABOLIC BONE DISEASE | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

![]() Vasopressin Secretion

Vasopressin Secretion

Basal vasopressin levels are unaltered in normal older individuals. Infusion of hypertonic saline, however, leads to a greater increase in plasma vasopressin in older as compared with younger persons. In contrast to the response to the hyperosmolar challenge, volume changes related to the assumption of upright posture are associated with less of a vasopressin response in older subjects as compared with the young. Both these findings might be explained by impaired baroreceptor input to the supraoptic nucleus. Volume expansion decreases osmoreceptor sensitivity. Hypertonic saline infusion results in volume expansion and thus decreases osmoreceptor sensitivity. If baroreceptor input is impaired in older adults, volume expansion would lead to a lesser dampening effect, and thus the vasopressin response to hyperosmolar stimuli would be increased.

Hyponatremia is a serious and often overlooked problem of the older patient. This syndrome is often associated with one of three general causes: (1) decreased renal blood flow with a decreased ability to excrete a water load; (2) diuretic administration leading to water intoxication (this condition is rapidly corrected by discontinuing diuretics); and (3) excess vasopressin secretion. Although a host of pulmonary disorders (e.g., pneumonia, tuberculosis, tumor) and central nervous

P.318

system disorders (e.g., stroke, meningitis, subdural hematoma) are associated with the syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) in any age group, older adults seem more prone to develop this complication. Certain drugs such as chlorpropamide and barbiturates may cause this syndrome more frequently in older individuals.

In addition to treatment directed at correcting the underlying cause, water restriction and hypertonic saline are indicated when the patient is symptomatic or the sodium level is below 120 mEq/L. Demethylchlortetracycline therapy may be needed in resistant patients with SIADH. This agent induces a partial nephrogenic diabetes insipidus and thus corrects the hyponatremia. Serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen should be closely monitored.

![]() Anabolic Hormones

Anabolic Hormones

Aging is associated with a decline in anabolic hormones (Lamberts et al., 1997). The declining activity of the growth hormone insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) axis with advancing age may contribute to the decrease in lean body mass and the increase in mass of adipose tissue that occur with aging. Increased lean body mass and decreased fat mass have been demonstrated to occur in men and women with growth hormone treatment. Men had marginal improvement of muscle strength and maximum oxygen consumption (VO2max), but women had no significant change. Adverse effects were frequent, including glucose intolerance and diabetes (Blackman et al., 2002).

Normal male aging is accompanied by a decline in testicular function, including a fall in serum levels of total testosterone and bioavailable testosterone. Only some men become hypogonadal. Androgens have many important physiological actions, including effects on muscle, bone, and bone marrow. However, little is known about the effects of the age-related decline in testicular function on androgen target organs. Studies of testosterone supplementation in older males demonstrate significant increases in lean body mass and significant decreases in biochemical parameters of bone resorption with testosterone treatment. However, there was also a significant increase in hematocrit and a sustained stimulation of prostate-specific antigen (Gruenewald and Matsumoto, 2003). Based on these results, growth hormone administration and testosterone supplementation cannot be recommended at this time for older men with normal or low normal levels of these anabolic hormones.

ANEMIA

Anemia is common in older adults, but should not be attributed simply to old age. Increased weakness, fatigue, and a mild anemia should not be dismissed as a manifestation of aging. In healthy older individuals, there is generally no

P.319

change in normal levels of hemoglobin from younger adult values. A low hemoglobin concentration at old age signifies disease and is associated with increased mortality (Izaks et al., 1999).

Signs and symptoms of anemia may be subtle. Table 12-8 lists some of these manifestations. Anemia should be considered in these circumstances. If anemia is present, a diagnostic evaluation is indicated to define the cause. The appearance of the peripheral blood smear along with the history and physical examination should direct the diagnostic evaluation as described below.

TABLE 12-8 SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS OF ANEMIA | ||

|---|---|---|

|

![]() Iron Deficiency

Iron Deficiency

Iron deficiency is the most common cause of anemia in older adults. Laboratory findings include hypochromia, microcytosis, low reticulocyte count, decreased serum iron, increased total iron-binding capacity (TIBC), low transferrin saturation, and absent bone marrow iron stores. A low serum iron and elevated TIBC indicate iron deficiency even in the absence of changes in red cell morphology. Because transferrin is reduced in many diseases, the TIBC may be normal or low in older patients with iron deficiency. However, a transferrin saturation of <10 percent would suggest iron deficiency even in the presence of a low TIBC. A low serum ferritin level is valuable in confirming the diagnosis because serum ferritin levels are below 12 mg/L in iron-deficiency anemia. Because inflammatory disease can elevate ferritin levels and liver disease can influence ferritin levels in either direction, the diagnosis of iron deficiency on the basis of a ferritin level must be made with a knowledge of the clinical situation.

Once iron deficiency is identified, it should be treated, and the cause of the anemia must be identified and corrected. Poor dietary intake of iron may contribute to iron deficiency in older adults. A dietary evaluation is important, both for foods that contain iron and for substances such as tea, which inhibit iron absorption. However, even in the presence of poor nutrition, evaluation for a bleeding lesion must be completed.

P.320

The stool should be examined for occult blood. Evaluation for a gastrointestinal lesion should be carried out in a patient with unexplained iron deficiency, even if the stool is negative for occult blood. Although gastrointestinal bleeding may be caused by drugs (especially certain analgesics, steroids, and alcohol), a gastrointestinal lesion must be excluded. Diverticulosis is a common cause of bleeding. Vascular ectasia of the cecum and ascending colon is increasingly a recognized cause of bleeding in older adults.

Replacement of iron should usually be by daily oral administration. The hemoglobin should improve in 10 days and be normal in approximately 6 weeks. Normal bone marrow iron stores should occur in an additional 4 months. If the anemia does not improve, one should consider nonadherence, continued bleeding, or an incorrect diagnosis. In unreliable patients, or when oral iron is not tolerated, parenteral iron replacement with iron dextran is indicated. Tolerance should be monitored with a test dose, and the patient should be closely observed for an acute reaction. Severe reactions occur less frequently with ferric gluconate, but a test dose should be used, as well. Parenteral iron should not be used routinely but it is an important therapeutic modality in the appropriate patient.

![]() Chronic Disease

Chronic Disease

The anemia of chronic disease may display many similarities with iron deficiency. In older adults, this anemia is frequently associated with chronic inflammatory diseases or neoplasia. There is a defect in bone marrow red cell production and a shortening of erythrocyte life span. The finding of hypochromia, low reticulocyte count, and low serum iron may lead to confusion with iron deficiency. When a high TIBC does not confirm the presence of iron deficiency, a ferritin level can differentiate the two anemias. It is low in iron deficiency and high-normal or elevated in the anemia of chronic disease. Treatment is addressed to the underlying chronic illness, because there is no specific therapy for this type of anemia.

![]() Sideroblastic Anemia

Sideroblastic Anemia

Sideroblastic anemia should be considered in an older patient with hypochromic anemia who does not have iron deficiency or a chronic disease. Serum iron and transferrin saturation are increased. Hence, synthesis is defective, leading to increased iron stores and the diagnostic finding of ringed sideroblasts in the marrow.

In older adults, sideroblastic anemia is commonly of the acquired type. The idiopathic group is usually refractory; only a few patients have a partial response to pyridoxine, but all should have a trial of pyridoxine. Although the prognosis is fairly good, approximately 10 percent of patients develop acute myeloblastic

P.321

leukemia. Secondary sideroblastic anemia may be associated with underlying diseases such as malignancies and chronic inflammatory diseases. Certain drugs and toxins can induce sideroblastic anemia (e.g., ethanol, lead, isoniazid, chloramphenicol). The drug-induced syndromes are corrected by administering pyridoxine. Table 12-9 lists the tests that will assist in the differential diagnosis of hypochromic anemias.

TABLE 12-9 DIFFERENTIAL TESTS IN HYPOCHROMIC ANEMIA | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

![]() Vitamin B12 and Folate Deficiency

Vitamin B12 and Folate Deficiency

Both vitamin B12 and folate deficiency may occur on a nutritional basis, although folate deficiency is the more common. Older people who live alone or who are alcoholics are most likely to have poor nutrition. Poor dietary intake of fresh fruits and vegetables may lead to folate deficiency; lack of meat, poultry, fish, eggs, and dairy products may lead to vitamin B12 deficiency. Vitamin B12 deficiency also occurs with the loss of intrinsic factor (pernicious anemia) and in gastrointestinal disorders associated with malabsorption of vitamin B12.

The laboratory findings are similar in the two deficiencies and include macrocytosis, hyperchromasia, hypersegmented neutrophils, and megaloblasts in the marrow. Leukopenia and thrombocytopenia may be present, and serum lactic dehydrogenase and bilirubin may be increased. The two are differentiated by measuring serum vitamin B12 and folate levels.

Treatment is with vitamin B12 or folic acid, as appropriate. However, because folate will correct the hematological disorder but not the neurological abnormalities of vitamin B12 deficiency, a correct diagnosis is essential before treatment.

P.322

NUTRITION

A discussion of nutrition and aging is limited by the lack of adequate studies, defined methods, and standards. Although it is generally accepted that intake moderately above recommended allowances is optimal, animal studies demonstrate increased longevity with lower caloric levels than recommended. In establishing nutritional requirements in humans, we must contend with the multiple factors that confound interpretation of available data, e.g., genetic factors, social environment, economic status, selection of food, and weak methods of assessing nutritional status.

Several national surveys have been performed to assess nutrition in older adults. Taken as a whole, these surveys do not indicate poor nutritional status or marked deficiency among older individuals in the United States, and suggest that intake relates more to health and poverty than to age. However, because folate and B12 deficiency are associated with an increased incidence of coronary artery disease, vitamin D deficiency is associated with osteoporosis, and vitamins A, C, and E have antioxidant effects that may be beneficial in prevention of certain chronic diseases, and because most people do not consume an optimal amount of all vitamins alone, some authors recommend that all adults take vitamin supplements (Fletcher and Fairfield, 2002).

![]() Vitamins, Protein, and Calcium

Vitamins, Protein, and Calcium

Table 12-10 summarizes nutritional requirements in older adults and demonstrates that there is no general increase in vitamin requirements with age. Studies on vitamin metabolism and requirements reveal no correlation between age and the requirement for vitamins A, B1, B2, or C. Vitamin B6 and vitamin B12 requirements also do not increase with age.

TABLE 12-10 NUTRITIONAL REQUIREMENTS IN OLDER PERSONS | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Studies on protein requirements are not in agreement. Based on nitrogen balance studies, estimates of protein requirement varied from 0.5 to more than 1.0 g/kg daily. Data on amino acid requirements are also conflicting: some data show increased requirements with age, and other data show no change.

For calcium, estimated requirements vary from 850 to 1020 mg/d, and some recommendations are as high as 1500 mg/d for postmenopausal women. Data on the correlation of dietary calcium intake and osteoporosis are conflicting. However, calcium and vitamin D supplementation do improve postmenopausal osteoporosis. It may be necessary to use calcium and vitamin D supplements to ensure adequate intake.

![]() Nutritional Deficiency and Physiological Impairments

Nutritional Deficiency and Physiological Impairments

There is little evidence to correlate age-associated nutritional deficiency with clinical findings. In a study on the consequences of vitamin A levels, there was no

P.323

significant correlation with dark adaptation, epithelial cells excreted, or percent keratinization. In other studies, there was no correlation between vitamin C levels and gingivitis or vitamin B12 and lactic acid, lactic dehydrogenase, or hematocrit. Older people with limited sun exposure may be at risk of vitamin D deficiency. Studies of older individuals in nursing homes suggest that these patients require 800 IU of vitamin D per day, double the usual recommended daily requirement. Data are conflicting on correlation of dietary calcium intake and osteoporosis. Problems in assessing this correlation include reduced calcium intake in older adults, altered calcium and phosphorus ratio, decreased protein intake, and acid-base balance.

![]() Reversal of Deficiency by Supplementation

Reversal of Deficiency by Supplementation

There is no impairment of vitamin or protein absorption in older adults. Data demonstrate conclusively that low vitamin levels in older adults can be reversed by administration of oral supplementation. Because these deficiencies can be corrected by dietary supplementation, they are most likely related to decreased intake.

![]() Caloric Needs

Caloric Needs

A study of 250 individuals age 23 to 99 demonstrated an age-associated decline in total caloric intake at the rate of 12.4 cal/d for a year. A yearly decline in basal metabolic rate accounted for 5.23 cal/d, while 7.6 cal/d related to reduction in other requirements, including physical exercise.

![]() Dietary Restriction and Food Additives

Dietary Restriction and Food Additives

Rats, mice, Drosophila, and other lower organisms have demonstrated that caloric restriction delays maturation and increases life span. The mechanism,

P.324

however, is not understood, but studies suggest that it may be related to decreased levels of IGF-1. Animals fed isocaloric diets but decreased protein have an increased life span. Based on the free radical theory of aging, it has been proposed that reducing agents would prolong life. Although the data are conflicting, some studies support this hypothesis. In certain animal models, caloric restriction decreases the incidence and delay onset of disease, including chronic glomerulonephritis, muscular dystrophy, and carcinogenesis. In humans, however, body weight below ideal is not associated with increased life span. In animal experiments, nutrition is maintained during caloric variation. This may not be true in humans, and thus may lead to the differing results.

Although the influence of dietary fiber on colonic carcinoma and diverticular disease is controversial, the use of dietary fiber to maintain bowel regularity has significant support, especially in older adults, where constipation may present a difficult clinical problem. When dietary intake of fiber is low, bran can be used as a supplement, particularly in cereals, breads, or as bran powder. Intake of bran can be adjusted to maintain normal bowel movements. Adequate fluid intake should also be assured.

Although the food industry is slowly responding, most canned foods still contain large amounts of added sodium and sugar. Because some of these are less expensive than fresh or frozen foods, older adults with limited incomes may use such prepared foods exclusively. When refined carbohydrates or sodium need to be restricted, these patients should be educated about the use of canned products.

INFECTIONS

Although it is proposed that alterations in host defense mechanisms predispose older adults to certain infections, there is little evidence to support this hypothesis. It may well be that environmental factors, physiological changes in other than the immune system, and specific diseases are the major elements in the increased frequency of certain infections in older adults (Table 12-11).

TABLE 12-11 FACTORS PREDISPOSING TO INFECTION IN OLDER ADULTS | |

|---|---|

|

Because the elderly more often have acute and chronic illnesses necessitating hospitalization and have longer hospital stays, they are at greater risk for nosocomial infections. Such hospitalizations put older patients at greater risk for gram-negative and Staphylococcus aureus infections. Physiological alterations (Chap. 1) such as occur in the lungs, bladder function, and the skin and glucose homeostasis may also predispose older adults to infections.

The incidence of malignancies is increased in older adults. Many of these neoplastic disorders, especially those of the hematological system, are associated with a higher frequency of infection. Immunosuppression during therapy is also a predisposing factor. The prevalence of diabetes mellitus is higher in older adults, thus predisposing them to more frequent urinary tract, soft-tissue, and

P.325

bone infections. Prostatic hypertrophy with obstruction predisposes the older male to urinary tract infections.

Phagocytic function appears to be unaltered in aging, as is the complement system. Cell-mediated immunity and, to a lesser extent, humoral immunity, is diminished in aging. The role that these changes play in predisposing older individuals to infection has not been well defined.

Many infections occur more frequently in older adults and are often associated with a higher morbidity and mortality. Atypical presentation of infection in some older patients may delay diagnosis and treatment. Underreporting of symptoms, impaired communication, coexisting diseases, and altered physiological responses to infection may contribute to altered presentations.

As an example, failure of patients to seek medical evaluation is one factor in the higher morbidity and mortality of appendicitis in the elderly. Difficulties in

P.326

communication may also alter presentation. Infections not directly involving the central nervous system may cause confusion in the elderly, particularly in individuals with preexisting dementia. The mechanism by which this occurs has not been defined. Acute unexplained functional deterioration should also alert the physician to a potential acute infectious process.

Existing chronic disease may mask an acute infection. Septic arthritis usually occurs in a previously abnormal joint. It may be difficult to distinguish clinically between exacerbation of the underlying arthritis and acute infection. Therefore, the physician should not be hesitant to examine synovial fluid in elderly patients with acute exacerbation of joint disease.

Febrile response may be blunted or absent in some older individuals with bacterial infections. This may obscure diagnosis and delay therapy. A poor febrile response may also be a negative prognostic factor. Conversely, a febrile response is more likely to indicate a bacterial rather than viral illness in older patients, particularly in the very old. The absence of leukocytosis in older patients should also not exclude consideration of a bacterial infection.

Antibiotic therapy in older adults, as in the young, is directed to the specific organism isolated. However, when empiric antimicrobial therapy is initiated, consideration should be given to including a third generation cephalosporin and/or aminoglycoside because gram-negative infections are more common regardless of the site. With all antibiotics, but particularly with the aminoglycosides, renal function must be considered and monitored for toxicity. Monitoring of drug blood level and renal function is mandatory with the aminoglycosides.

The spectrum of pathogens causing common infections in the elderly is often different than that in younger adults (Table 12-12). The frequency of gram-negative bacilli increases in each category. Pneumonia is the most frequent cause of death caused by infection in geriatric patients. Streptococcus pneumoniae is the most common cause of pneumonia in the elderly, but gram-negative bacilli increase in prevalence, particularly in the nursing home setting (Yoshikawa, 1999). Annual immunization against influenza, and at least one pneumococcal vaccination are recommended for all persons 65 years of age and older. Nearly 50 percent of infective endocarditis cases occur in older adults. The underlying cardiac lesion is often caused by atherosclerotic and degenerative valve diseases, as well as by prosthetic valves. Bacterial meningitis is an infection primarily of early childhood and late adulthood. Mortality in the elderly ranges from 50 to 70 percent. S. pneumoniae is the most frequent pathogen, but older patients may be infected with Listeria monocytogenes or gram-negative bacilli.

TABLE 12-12 PATHOGENS OF COMMON INFECTIONS IN OLDER ADULTS | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

The incidence of tuberculosis is on the rise again. Older persons of both sexes among all racial and ethnic groups are especially at risk for tuberculosis. This cohort has lived through a period of higher incidence of tuberculosis, has probably not been treated with isonicotinic acid hydrazide (INH) prophylaxis, and may have predisposing factors such as physiological changes, malnutrition, and underlying disease that may lead to reactivation. Older patients are also at increased risk for

P.327

primary infection. This is particularly the case for older patients in long-term care institutions.

Tuberculosis screening programs should be implemented in long-term care facilities because of this increased risk and because of the potential to prevent active disease among patients whose skin test converts to a strongly positive reaction (see Chap. 16). The American Thoracic Society now recommends preventive therapy for certain types of patients regardless of age, including insulin-dependent diabetic patients, those on steroids and other immunosuppressive treatment, patients with end-stage renal disease, and patients who have lost a large amount of weight rapidly. A useful rule in geriatric care is to suspect tuberculosis when a patient is inexplicably failing.

Several studies suggest that bacteriuria is associated with increased mortality in the elderly. However, other studies do not confirm this finding. Most of these non-confirming studies did not differentiate between the effect of bacteriuria and age and/or concomitant disease on mortality. When adjusted for age, fatal diseases associated with bacteriuria account for the increase in mortality among older patients with bacteriuria.

Several previous studies in elderly hospitalized or institutionalized patients have not revealed antimicrobial therapy for bacteriuria to be effective because of the high rate of recurring infection. One study in older ambulatory nonhospitalized

P.328

women with asymptomatic bacteriuria demonstrated that short-course antimicrobial therapy is effective in eliminating bacteriuria in most of the women for at least a 6-month period. Survival was not an outcome measure.

Bacteriuria in older persons is common and usually asymptomatic. At present, in the absence of obstructive uropathy, no evidence exists to support the routine use of antimicrobial therapy for asymptomatic bacteriuria in older persons. Among bacteriuric patients with urinary incontinence and no other symptoms of urinary tract infection, the bacteriuria should be eradicated as part of the initial assessment of the incontinence (see Chap. 8).

DISORDERS OF TEMPERATURE REGULATION

Temperature dysregulation in the elderly demonstrates the narrowing of homeostatic mechanisms that occurs with advancing age. Older persons are less able to adjust to extremes of environmental temperatures. Hypo- and hyperthermic states are predominantly disorders of older adults. Despite underreporting of these disorders, there is evidence that morbidity and mortality increase during particularly hot or cold periods, especially among ill elderly. Much of this illness is caused by an increased incidence of cardiovascular disorders (myocardial infarction and stroke) or infectious diseases (pneumonia) during these periods.

Hypothermia is a common finding among older adults during the winter, when homes are heated at less than 70 F (21 C).

![]() Pathophysiology

Pathophysiology

Impaired temperature perception, diminished sweating in hyperthermia, and abnormal vasoconstrictor response in hypothermia are major pathophysiological mechanisms in these disorders.

![]() Hypothermia

Hypothermia

Hypothermia is defined as a core temperature (rectal, esophageal, tympanic) below 95 F (35 C). Essential to the diagnosis is early recognition with a low-recording thermometer.

Table 12-13 illustrates the clinical spectrum of hypothermia. Because early signs are nonspecific and subtle, a high index of suspicion must exist to allow an early diagnosis. A history of known or potential exposure is helpful, but older patients can become hypothermic at modest temperatures. Frequently the most difficult differential diagnosis in more severe hypothermia is hypothyroidism. A previous history of thyroid disease, a neck scar from previous thyroid surgery, and a delay in the relaxation phase of the deep tendon reflexes may assist in diagnosing

P.329

hypothyroidism. Patients may sometimes be mistaken for dead. Case reports reveal patients who have survived after being discovered without respiration and pulse.

TABLE 12-13 CLINICAL PRESENTATION OF HYPOTHERMIA | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

The most significant early complications are arrhythmias and cardiorespiratory arrests. Later complications involve the pulmonary, gastrointestinal, and renal systems. Electrocardiogram (ECG) abnormalities are frequent. The most specific ECG finding is the J wave (Osborn wave) following the QRS complex. This abnormality disappears as temperature returns to normal.

General supportive therapy for severe hypothermia consists of intensive care management of complicated multisystem dysfunctions. Every attempt should be made to assess and treat any contributing medical disorder (e.g., infection, hypothyroidism, hypoglycemia). Hypothermia in older patients should promptly be treated as sepsis unless proven otherwise. While patients should have continuous ECG monitoring, central lines should be avoided if possible because of myocardial irritability. Because there is delayed metabolism, most drugs have little effect on a severely hypothermic patient, but they may cause problems once the patient is rewarmed. It is preferable to stabilize the patient and immediately undertake specific rewarming techniques. Serious arrhythmias, acidosis, and fluid and electrolyte disorders will usually respond to therapy only after rewarming has been accomplished.

P.330

Passive rewarming is generally adequate for those with mild hypothermia (>89.6 F [>32 C]). Active external rewarming has been associated with increased morbidity and mortality because cold blood may suddenly be shunted to the core, further decreasing core temperature; peripheral vasodilatation can precipitate hypovolemic shock by decreasing circulatory blood volume. For more severe hypothermia (<89.6 F [<32 C]), core rewarming is necessary. Several techniques for core rewarming have been used, but positive results have been reported only from small, uncontrolled studies. Peritoneal dialysis and inhalation rewarming may be the most practical techniques in the majority of institutions.

Mortality is usually greater than 50 percent for severe hypothermia. It increases with age and is particularly related to underlying disease.

![]() Hyperthermia

Hyperthermia

Heat stroke is defined as a failure to maintain body temperature and is characterized by a core temperature of >105 F (>40.6 C), severe central nervous system dysfunction (psychosis, delirium, coma), and anhidrosis (hot, dry skin). The two groups primarily affected are older adults who are chronically ill and the young undergoing strenuous exercise. Mortality is as high as 80 percent once this syndrome is manifest.

There are multiple predisposing factors for heat stroke in older adults, but most often there is a prolonged heat wave. The diagnosis requires a high level of suspicion. In view of the poor survival, efforts must be directed toward prevention. Older patients should be cautioned about the dangers of hot weather. For those at particularly high risk, temporary relocation to more protected environments should be considered.

Early manifestations of heat exhaustion are nonspecific (Table 12-14). Later, severe central nervous system dysfunction and anhidrosis develop.

TABLE 12-14 CLINICAL PRESENTATION OF HYPERTHERMIA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

P.331

Table 12-15 lists some of the more serious complications resulting from heat damage to organ systems. Once the full syndrome has developed for any length of time, the prognosis is very poor. While management at this stage requires intense multisystem care, the key is rapid specific therapy consisting of cooling to 102 F (38.9 C) within the first hour. Ice packs and ice-water immersion are superior to convection cooling with alcohol sponge baths or electric fans.

TABLE 12-15 COMPLICATIONS OF HEAT STROKE | |

|---|---|

|

Prevention appears to be the most appropriate approach to management of temperature dysregulation in older adults. Education of older adults to their susceptibility to hypo- and hyperthermia in extremes of environmental temperature, education as to appropriate behavior in such conditions, and close monitoring of the most vulnerable older adults should help reduce the morbidity and mortality from these disorders.

P.332

References

Biondi B, Fazio S, Palmieri EA, et al: Left ventricular diastolic dysfunction in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 84:2064 2067, 1999.

Blackman MR, Sorkin JD, Munzer T, et al: Growth hormone and sex steroid administration in healthy aged women and men: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 288:2282 2292, 2002.

Boul NG, Haddad E, Kenny GP, et al: Effects of exercise on glycemic control and body mass in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. JAMA 286:1218 1227, 2001.

Cooper DS: Subclinical hypothyroidism. N Engl J Med 345:260 265, 2001.

Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group: Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Eng J Med 346:393 403, 2002.

Fletcher RH, Fairfield KM: Vitamins for chronic disease prevention: clinical applications. JAMA 287:3127 3129, 2002.

Gruenewald DA, Matsumoto AM: Testosterone supplementation therapy for older men: potential benefits and risks. J Am Geriatr Soc 51:101 115, 2003.

Hak AE, Pols HAP, Visser TJ, et al: Subclinical hypothyroidism is an independent risk factor for atherosclerosis and myocardial infarction in elderly women: the Rotterdam study. Ann Intern Med 132:270 278, 2000.

Huang ES, Meigs JB, Singer DE: The effect of interventions to prevent cardiovascular disease in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Med 111:633 642, 2001.

Huber G, Staub J-J, Meier C, et al: Prospective study of the spontaneous course of subclinical hypothyroidism: prognostic value of thyrotropin, thyroid reserve, and thyroid antibodies. J Clin Endocrinol Metabl 87:3221 3226, 2002.

Inzucchi SE, Maggs DG, Spollett GR, et al: Efficacy and metabolic effects of metformin and troglitazone in type II diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 338:867 872, 1998.

Izaks GJ, Westendorp RG, Knook DL: The definition of anemia in older persons. JAMA 281:1714 1717, 1999.

Ku S: Algorithms replace sliding scale insulin orders. Drug Ther Topics 31:49 53, 2002.

Lamberts SWJ, van den Beld AW, van der Lely A-J: The endocrinology of aging. Science 278:419 424, 1997.

Meneilly GS, Tessier D: Diabetes in elderly adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 56A:M5 M13, 2001.

Ravid M, Brosh D, Levi Z, et al: Use of enalapril to attenuate decline in renal function in normotensive, normoalbuminuric patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann Intern Med 128:982 988, 1998.

Silverberg SJ, Bilezikian JP, Bone HG, et al: Therapeutic controversies in primary hyperparathyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 84:2275 2282, 1999.

Toft AD: Subclinical hyperthyroidism. N Engl J Med 345:512 516, 2001.

Turner RC, Cull CA, Frighi V, et al: Glycemic control with diet, sulfonylurea, metformin, or insulin in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA 281:2005 2012, 1999.

P.333

UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group: Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). Lancet 352:837 852, 1998a.

UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group: Effect of intensive blood-glucose control with metformin on complications in overweight patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 34). Lancet 352:854 865, 1998b.

UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group: Tight blood pressure control and risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes: UKPDS 38. BMJ 317:703 712, 1998c.

US Preventive Services Task Force: Screening for type 2 diabetes mellitus in adults: recommendations and rationale. Ann Intern Med 138:212 214, 2003.

Yoshikawa TT: State of infectious diseases health care in older persons. Clin Geriatr Med 7:55 58, 1999.

Suggested Readings

Anonymous: Antimicrobial prophylaxis in surgery. Med Lett Drugs Ther 41:75 80, 1999.

Anonymous: The choice of antibacterial drugs. Med Lett Drugs Ther 41:95 104, 1999.

Treatment of hypothermia. Med Lett Drugs Ther 28:123 124, 1986.

Bartlett JG: Antibiotic-associated diarrhea. N Engl J Med 346:334 339, 2002.

Belshe RB: Influenza prevention and treatment: current practices and new horizons. Ann Intern Med 131:621 623, 1999.

Bentley DW, Bradley S, High K, et al: Practice guideline for evaluation of fever and infection in long-term care facilities. J Am Geriatr Soc 49:210 222, 2001.

Bouchama A, Knochel JP: Heat Stroke. N Engl J Med 346:1978 1988, 2002.

Brady MA, Perron WJ: Electrocardiographic manifestations of hypothermia. Am J Emerg Med 20:314 326, 2002.

Chandalia M, Garg A, Lutjohann D, et al: Beneficial effects of high dietary fiber intake in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 342:1392 1398, 2000.

Davis PJ, Davis FB: Hyperthyroidism in patients over the age of 60 years. Medicine (Baltimore) 53:161 181, 1974.

Elia M, Ritz P, Stubbs RJ: Total energy expenditure in the elderly. Eur J Clin Nutr 54:S92 S103, 2000.

Federman DD: Hyperthyroidism in the geriatric population. Hosp Pract 26:61 76, 1991.

Gambert SR: Effect of age on thyroid hormone physiology and function. J Am Geriatr Soc 33:360 365, 1985.

Gress TW, Nieto J, Shahar E, et al: Hypertension and antihypertensive therapy as risk factors for type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 342:905 912, 2000.

Lipschitz DA: An overview of anemia in older patients. Older Patient 2:5 11, 1988.

Mahler RJ, Adler ML: Type 2 diabetes mellitus: update on diagnosis, pathophysiology, and treatment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 84:1165 1171, 1999.

P.334

Morley JE, Mooradian AD, Silver AJ, et al: Nutrition in the elderly. Ann Intern Med 109:890 904, 1988.

Mylonakis E, Calderwood SB: Infective endocarditis in adults. N Engl J Med 345:1318 1330, 2001.

Sawin CT, Castelli WP, Hershman JM, et al: The aging thyroid: thyroid deficiency in the Framingham Study. Arch Intern Med 145:1386 1388, 1985.

Stead WW, To T, Harrison RW, et al: Benefit-risk considerations in preventive treatment for tuberculosis in elderly persons. Ann Intern Med 107:843 845, 1987.

Thomas FB, Mazzaferi EL, Skillman TB: Apathetic thyrotoxicosis: a distinctive clinical and laboratory entity. Ann Intern Med 72:679 685, 1970.

Trevino A, Bazi B, Beller BM, et al: The characteristic electrocardiogram of accidental hypothermia. Arch Intern Med 127:470 473, 1971.

Trivalle C, Doucet J, Chassagne P, et al: Differences in the signs and symptoms of hyperthyroidism in older and younger patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 44:50 53, 1996.

Tuomilehto J, Lindstrom J, Eriksson JG, et al: Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med 344:1343 1350, 2001.

UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group: Efficacy of atenolol and captopril in reducing risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes: UKPDS 39. BMJ 371:713 719, 1998.

Walsh JR: Hematologic disorders in the elderly. West J Med 135:445 446, 1981.

Yoshikawa TT: Infectious diseases. Clin Geriatr Med 8:701 945, 1992.

Yoshikawa TT: Tuberculosis in aging adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 40:178 187, 1992.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 23