Challenging the Frictionless Paradigm

|

The frictionless vision of the network society surely grasps the novelty and disruptive character of the Internet communication models and their impact on the economy, but we believe it does not come to terms with the complexity of the Internet society, its economics and its changes. We need a more fine-grained analysis of these changes, trying to understand more precisely the nature of these new forms of governance and their new hierarchies (Mandelli, 2001b).

We claim that the frictionless paradigm does not describe the complexity of the Internet society because it is not true that:

-

network connections automatically drive information symmetry and a power-shift in relationships;

-

network connections automatically create social cooperation and relationships based on trust;

-

relationships based on trust are necessarily non-hierarchical.

Trust, Delegation and Legitimacy

Delegation is a tool for managing complexity in complex systems. For Castelfranchi and Falcone (1999), trust means delegation. This is why, differently from what it is true for the majority of scholarly definitions of trust (Castaldo, 2002), we propose to focus on what the trustor misses, instead of what he chooses. He misses variety. The trustor gives up power, when he gives up the exploration of potentially better alternatives of cognitive mediation. At the system (or sub-system) level, delegation is the structure of power relationships in the system. Even though trust can drive cooperation, this does not necessarily mean that trust lowers relationship hierarchies.

Trust is not the opposite of hierarchy because trust is a form of hierarchy (cognitive selection). But, it is also variation. All cognitive hierarchies are at the same time selections (delegation, reduction of variation) and increase in variation (symbolic value added by cognitive mediations and new associations). Mediation and delegation are not the same concepts, even though they are connected. Mediation focuses on the constructivist value added by symbolic interaction in the cognitive and social encounters. Delegation focuses on selection and complexity reduction.

If we analyze the infomediation role of trust, we can more easily understand its relationship with delegation and power (Mandelli, 2001). Weber (1919) defined power as the possibility of imposing one's will upon the behavior of others. In later studies (French & Raven, 1959), power explicitly includes the ability to influence values and beliefs. French and Raven (1959) define power as the ability to influence others to believe, behave, or to value as those in power desire them to or to strengthen, validate, or confirm present beliefs, behaviors, or values.

But power is not all the same. Since Weber's work on legitimacy (1919), the source of delegation has been one of the core research questions in social studies. Coercive power is based on the threat of force. Force is not limited to physical means; it is also social, emotional, political, or economic. We know that delegation (opposite to coercion) can be based not necessarily on tradition and charisma, but rather on shared rules and professional specialization. Weber (1919) defined authority as the means by which dominance was cloaked with legitimacy and the dominated accepted their fate. Legitimacy can be based on charismatic affect, tradition, or legal/shared rules.

Also, according to French and Raven (1959), power manifests itself in several forms. Among these are: expert power, reward power, legitimate power, referent power, and coercive power. In their stricter definition, legitimate power results from one's being appointed to a position of authority. Such legitimacy is conferred by others and this legitimacy can be revoked by the original granters. Referent power is the affective tie to one's community or group. Expert power is based on the idea that experts are in a better position for selecting the best solutions for the collectivity.

According to Morris (2001), "something is legitimate if it is in accord with the norms, values, beliefs, practices and procedures accepted by a group" (p. 2). In his perspective legitimacy is not concerned with self-interest: "... the legitimacy of any feature of a social structure is indicated by the fact that it is supported by those who have nothing to gain from it, even by those who would benefit from some other structure" (p. 5).

These ideas on how human communities legitimate power and delegation are crucial for understanding how democratic institutions can be built on power asymmetries and delegation. Representative democracy government mechanisms are based on delegated decisional power. It may be important also for understanding the legitimacy of coordination of social asymmetry and infomediation.

According to Schudson (1973), the shared rule and professional type of delegation is the way news media legitimate their gatekeeping role in society. News values (Gans, 1979) define the professional and the social responsibility rules of the game. Complexity in this case is managed by delegated selection; selection is based on negotiated agendas at the policy level and shared social-responsibility rules (McCombs, Shaw & Weaver, 1997; Semetko & Mandelli, 1997). In this view, cognitive and cultural hierarchies, in other words information and value delegation, come out from professional delegation and civic trust. Symbolic coercion (authority not legitimated) comes from the information divide, based on the differential access to the gatekeeping system, influenced by economic, cognitive, and social resources (McCombs et al., 1997).

In our digital society the sources of information are multiplied and more difficult to select. Different kind of new infomediaries on digital networks have entered the scene, in particular portals and virtual communities. These higher-level social actors have different agendas and value priorities. We must understand the logics of these new cognitive policy arenas in digital societies and economies. This goal is too broad to be addressed in this work. Here we focus on one of its core components: the role of trust in delegation and cooperation.

The Symmetry Fallacy, the New Transaction Costs and the Economics of Mediation

We argue that the reason why the dominant intellectual framework in Internet economics does not help face the challenges of management in complex digital networks is because it is based on what we call "the communication symmetry fallacy" (Mandelli, 2001b, 2002b). This is the idea that technological symmetry between all pairs of nodes in digital networks (the potential total connectivity provided by the digital infrastructure of networks) creates a cognitive and relational symmetry in the same pairs of nodes. It is the old communication as transportation metaphor, critiqued in mass communication research (Carey, 1989), now applied to the networked world.

As mediations are not simply content channels, relationships are not automatic. They are context-based and are the outcomes not only of choices, but also of inertia, randomness and learning (Nelson & Winter, 1982; Dimaggio & Powell, 1991; Macy, 1998; Rullani & Vicari, 1999; Castelfranchi, 2000). Choices can be instrumentally and not instrumentally driven (Castelfranchi, 1998), but they are not "order for free." They cost technology, information, trust, values, attention and time resources at the node level, even when the cooperation between those pairs of nodes is self-organized, that is, not coordinated centrally (Mandelli, 2002).

Friction-free relationships and friction-free markets are not more common on the digital web than in traditional communication spaces, because transaction costs at the node-level on digital networks are not eliminated, they are just changed. For the particular cognitive logistics of the Internet (Mandelli, 1997, 1998), it can be easier to reach out to somebody (once we know where to look) and switch from him to another partner. However, it can be much more difficult to establish an efficient and long-lasting relationship, considering the complexity of these dynamic encounters, their uncertainty, and the cognitive and social resources we have to bring to them (Mandelli, 1998; Jarvenpaa & Leidner, 1998).

The communication symmetry idea does not take into account the complexity of social and cognitive networks. We are creating these networks thanks to the technological web, and the individual and system-level need for new hierarchical (though dynamical and flexible) structures of selection and delegation, made of different layers of dynamically interconnected cognitive worlds (Mandelli, 2001).

The availability of a technologically frictionless communication channel does not automatically increase information and relationship variety for social mediation. We reduce our access to diversity in relationships because of cultural inertia (Dimaggio & Powel, 1991) or according to our need of economizing on cognitive investments (Neuman, 1991; Mandelli, 1997b, 2002). But, we also reduce our access to diversity because of the information asymmetries structured by the economics of infomediation and content (Neuman, 1991; Mandelli, 1998; Shapiro & Varian, 1998; Vicari, 2001).

But if network society is not the all-symmetrically-connected society that the new frictionless paradigm envisioned, it is also very different from the only-locally-connected societies of the past. If societies are communication networks, the structure of the network matters. Digital communication provides a different infrastructure and structure to our network society. If we study Internet relationships using the approach suggested by connectionism applied to virtuality (Vicari, 2001), we can recognize new hierarchies at the level of the structural architecture of connections, at the level of the stock of resources available to the individual nodes in relationships, and at the level of the connection activation mechanisms (Mandelli, 2001).

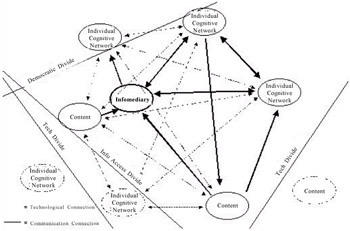

We can easily grasp this, applied to the so-called digital divide problem in the network society (Norris, 2001; Dimaggio & Hargittai, 2001; Cawkell, 2001). People have access to the technological connections of the new social network (they become Internet users) depending on their social and cognitive resources, that is, technology adoption, education, computer literacy. Researchers call this the first dimension of digital divide (Norris, 2000). Also, they have access to the information and the relationships on the network, depending on their ability to reach technologically and cognitively content and other people and being reached by content and other people. This content and relationship access, what Norris (2000) calls the democratic divide, is limited by the infomediation/gatekeeping system [1] and its business model (Figure 1). A general portal is less precise than a specialized navigation service. A walled-garden portal like AOL limits more the options and the diversity of navigation sources than the other types of portals or free navigation on the World Wide Web. But this access is also limited by users' language, and users' stock of available tangible (money) and intangible resources (attention, time, cognitive sophistication, social capital).

Figure 1: Hierarchies on the Network (Mandelli, 2001)

The infomediation structures on digital networks can be very different (Mandelli, 1999). They can be very complex (different distributed layers and actors of infomediation, all connected by hypermedia rings of collaborative services) or very top-down and simple like in the walled-garden model. They respond to specific functions (trade-off between cognitive efficiency and diversity access for the user) and have different legitimacy for their gatekeeping role (Mandelli, 2001).

Besides accessing the content differently, Internet users can also interact with content and people differently, depending on whether the formats of the channel and the medium are designed to allow interactivity, but also whether they are able and interested in doing it, according to rational and non-rational rules of activation.

Each elementary and second-level node on the network faces transaction costs (costs of cognitive mediation) when they activate connections with other nodes and sub-systems. These transaction costs are made by all the resources invested in the symbolic mediation:

-

Monetary cost of connection (if the infomediation infrastructure is not based on free-connection business models)

-

Time

-

Attention

-

Knowledge

-

Social capital

-

Freedom (privacy)

Knowledge is to be conceived both as cognitive sophistication (education and technological literacy for individuals) and cognitive frameworks. Social capital is defined in Putnam (1993, p. 167) as those features of social organization, such as trust, norms and networks, that can improve the efficiency of society by facilitating coordinated actions.

All the intangible resources produce costs, even though knowledge and social capital are subjected to the law of increasing returns (Shapiro & Varian, 1998), meaning that their value does not decrease with use. Knowledge and social capital do not devalue with use, but they require often huge investments to be built, that is they create sunk costs. Networks still have sunk costs at the node level, but these sunk costs are different than before; they are mostly based on intangible investments. We know that sunk costs drive lock-in strategies (Shapiro & Varian, 1998) and this is one of the major sources of hierarchy on the social and economic networks. More in general, the new transaction costs have the following sources:

-

The cognitive complexity of the increasingly interconnected system;

-

The economies of scale (supply side and demand side) and scope in the information production;

-

The tangible and intangible resources required for accessing the content and the infomediation infrastructure of the network;

-

The tangible and intangible resources requested by the relationships with the connected nodes.

[1]Returning to the original meaning built in the early discussions on the web, and beyond the later and more restricted versions of the concept (Hagel & Singer, 1999), we define infomediaries (see Mandelli, 2001) as systems that make the interaction of cognitive sub-systems (individual and second-level) possible and more efficient. These systems provide symbolic mediation (association), beyond functional connectivity. They were the media in the mass communication era. They are the new infomediaries (portals, communities, content sites on the web) in the Internet era.

|

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 143