STAGE ONE ANALYSIS

|

At this stage there was no apparent need to adapt the method much. The data had been collected using the contextual interview and so, for Stage One, the data were analyzed using Contextual Design techniques. These are outlined below.

The Interpretation Session

The interpretation session is the first main stage of analysis. This is an important stage because under normal circumstances Contextual Design is intended to be a team activity. A variety of interviewers will have interviewed a range of users, and it is important for all members of the team to gain a shared understanding of all the customers. The aims of this session are:

-

To get better data—people question the interviewer who therefore remembers more than if (s)he were working alone.

-

To create a written record of customer insights.

-

To have effective cross-function co-operation. The interested parties in the project are likely to come from a range of functions.

-

To obtain multiple perspectives on the problem—as each team member brings a different focus.

-

To develop a shared perspective—through discussion.

-

For team members to have true involvement in the data—data is revealed interactively rather than through a presentation.

-

To make better use of time—questions would still have to be asked of the interviewer. The interpretation session brings all the questioning together.

The members of the team are intended to play different roles in the interpretation session. The interviewer talks the rest of the team through his/her interview. Some members of the team are creating the work models. One member notes insights and observations. There is also a member whose role is to ensure the meeting stays on track. Any other members of the team are expected to actively participate by asking questions, offering insights and interpretations, and suggesting ideas.

The interpretation session could clearly not be run as a team session in this study as I was primarily working alone. This did not prove to be a major problem as all the interviews had been recorded and transcribed, and were supported by detailed handwritten notes made during the interviews. This meant that the interview recall was very good without the need for prompting and questioning. Working through the data, I was creating the different models and recording insights and observations. The effect of this was that it gave me an intimate knowledge of the data. The major disadvantage was that by working alone there was no possibility of extra insights that might have been offered by other team members.

The Work Models

The second stage of the analysis is to create five work models. The work models are created in the interpretation session and are each intended to represent one aspect of work for design. They were developed over time based on the experience of the design problems encountered by Beyer and Holtzblatt (1998). Although the final aim of the case study was not to design a system, the models were all used for the first part of the study as a means of handling the large amount of rich raw data and providing further insights.

The Flow Model

The Flow Model is concerned with how people divide up responsibilities among roles, and how they co-ordinate with each other while they do the work. In other words, it is used to explore distributed co-ordination. The Flow Model models communication flow and distinguishes between:

-

Individuals who do the work.

-

The responsibilities of the individual (or the role).

-

Groups—these are people who have common goals.

-

Flow—communication between people. This might be verbal or it may be in the form of artefacts.

-

Artefacts—both physical and conceptual.

-

Communication Topic, for example, asking for help.

-

Places—where people go to and from to get the work done.

-

Breakdowns—problems in communication or co-ordination.

It was anticipated that this model would be particularly relevant for the case study, in particular its emphasis on communication, distributed coordination, and artefacts. A Flow Model was created for each of the CoP members to show the communications observed during the time spent with that person. An example is shown in Appendix 2.

The Sequence Model

The Sequence Model is designed to model the ordering of work tasks, that is, what triggers the task, what the steps are in the task, and what is the intent behind the work. It is based on the principle that the actions that people take reveal the strategy they are employing and what is important to them. If a system were to build on these aspects, it could improve the work. It is essential to see the intents (both explicit and implicit) behind the work. Simply automating the tasks will cause a system to be rejected if the intents are not catered to.

The Sequence Model shows:

-

Intents: What the sequence is intended to achieve.

-

Triggers that cause the sequence of actions.

-

Steps, that is, what actually happened.

-

Order. This aspect is shown using loops, branches, and arrows to connect the steps.

-

Breakdowns or problems in executing the steps.

At first glance, it was felt that this model appeared to be less relevant than the Flow Model but could provide useful insights into interactions between people, both co-located and distributed. A range of Sequence Models was created from the transcripts, covering both contextual interviews and meeting observation. An example of one of the Sequence Models is in Appendix 3.

The Artefact Model

People create and adapt artefacts to use in the course of their work, for example forms, documents, lists, and spreadsheets. The structure of an artefact can show the conceptual distinctions of the work. The Artefact Model is designed to show the structure and the information content.

It shows:

-

The information that is presented by the artefact.

-

The parts of the artefact.

-

The structure of the parts.

-

Annotations that show the informal use.

-

The Presentation. This might be the use of color, white space, or layout.

-

Other conceptual distinctions such as past/present/future.

-

Usage, for example, when the artefact was created and how it is used.

-

Breakdowns—problems when using the artefact.

The use of artefacts in a distributed Community of Practice was a particular focus in the case study, and it was felt that the Artefact Model would be a particularly useful way of exploring the use of the artefacts. An Artefact Model was created for each of the physical artefacts that were collected during the course of the investigation; however, particular attention was paid to the planning document. Unfortunately the Artefact Model did not prove to be as useful as anticipated, as it is more suited to everyday artefacts that people use regularly in their work. This was not the focus as such in WWITMan, and the artefacts that were relevant to the focus were created during the work. The planning document proved to be of particular interest, and it was the process of creation and its use in interactions that were more relevant than the artefact itself.

The Cultural Model

The cultural context of the work is of immense importance. If a system does not take into account the culture of the people it is intended to support, it will not be successful. The cultural context includes the organisational policies, national culture, how people see themselves, the formality of the organisation, and laws, rules, and regulations.

The Cultural Model, however, has a more restricted view of culture and represents:

-

Influencers, that is, people who affect or constrain work.

-

The extent: To what degree the influence affects the work. This is shown by overlap of components on the diagram.

-

Influence on the work, and the direction of the influence.

-

Breakdowns: the problems that interfere with the work.

Cultural aspects have a large bearing on work that is carried out by distributed international groups. Therefore, it was anticipated that the Cultural Model would also be of particular relevance. One single Cultural Model for the CoP was created during the course of the study, rather than one for each member. The resulting model was very large, hence a small section of it is reproduced in Appendix 4 as an example.

The Physical Model

The fifth and final model is intended to represent the physical environment and how it either enables or supports the work (or, indeed, how it hinders the work). The reason for this is also geared towards system design; that is, any system that is designed will have to live within that environment. It must therefore take into account the constraints, otherwise it will cause problems for the users.

The Physical Model shows:

-

Places—where the work takes place.

-

The physical aspects of the environment that limit the space, for example, walls, desks, and other large objects.

-

Usage and movement—how people move within the space.

-

Tools, hardware, software, and communication.

-

Artefacts that are created and passed around.

-

Breakdowns that show how the physical environment interferes with the work.

As the group being studied was part of a distributed group, it was not felt that the physical model would contribute a great deal to the study, and this proved to be the case as the immediate environment was modeled for each respondent. However, it may have been useful to have created a higher level model of the environment to show the problems the group encounters when operating in the distributed environment. Such a model could have demonstrated the differences in mode of operation when interacting with colleagues on site and when interacting with distant colleagues. These aspects, however, were brought out through the other models and the Affinity, but a high level physical model to show this would also have been useful.

Consolidation and the Affinity Diagram

After the creation of the models, the next step is to consolidate. Beyer and Holtzblatt (1998) describe this as "the inductive process of bringing all the individual data together and building one Affinity diagram and one set of models that represent the whole customer population" (p. 154).

To create an Affinity, all the insights and observations that have been recorded during the interpretation session are organised into hierarchies in order to show common issues and themes. It is an inductive process and is done by placing a note on the wall, and then adding any others that the researcher feels fit with it. If a note doesn't fit with any on the wall, a new category is started. When the notes are all allocated they are organised into hierarchies by grouping together and providing meaningful names. In a normal contextual enquiry, the Affinity diagram would be based on a large number of notes and would therefore be a team activity.

When the Affinity has been created, all the data are arranged clearly and present the issues. The researchers then "walk" the Affinity; that is, they "read" the wall. Reading the notes raises further issues that might need to be addressed in further interviews or it might lead to the creation of ideas. The intention is for anyone to be able to walk the Affinity—researchers, customers, and outsiders. It is intended to be a collaborative activity. As WWITMan's organisation was many miles distant, it was impractical for the respondents to visit; therefore, my departmental colleagues were invited to walk the Affinity and provide their insights and feedback.

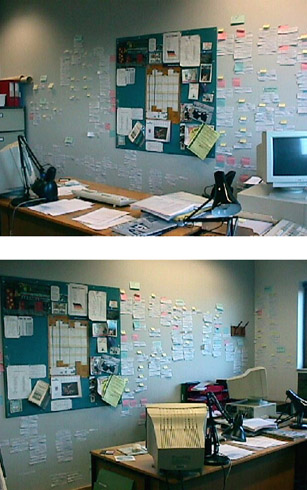

Figure 1: The Affinity

Having created and walked the Affinity, the work models had to be consolidated. The aim of consolidation is to move to one set of models representing the study population. Therefore, each set of models is combined to create one.

The Flow Model

The Flow Model consolidation is intended to show the communication patterns that underpin the business of the study population. Consolidating the Flow Model moves from individuals to the roles played by those individuals. I hoped that this would provide insights into the interactions within the CoP and also show the roles undertaken by the members in sustaining the CoP.

The first step is to create a complete list of responsibilities for each individual. Undertaking this process may also bring previously overlooked responsibilities to light. Having listed the responsibilities, roles can be identified. The stages that were followed in consolidating the Flow Model were adapted from Beyer and Holtzblatt (1998) to cater for the tight focus and population of the study, which would be smaller than that of a normal Contextual Design exercise.

StepOne: Generate a complete list of responsibilities for each individual.

Step Two: Examine the flows to see if they suggest any other informal roles.

Step Three: Look for roles and name them.

Step Four: Combine the people into roles.

Step Five: Combine the roles into another flow model and bring in flows from the original flow models.

Examples of these stages and a section of the consolidated Flow Model are shown in Appendix 5. Consolidating the Flow Model proved to be a useful exercise. Four main roles were identified, and although not all four were totally relevant to the focus of the study, the model and the process of creating it led to insights into the data and the situation of the study group.

The Sequence Model

It was doubtful whether the consolidated Sequence Model would be particularly relevant, as its purpose is to examine a particular task. The CoP in the study did not have particular repeated tasks, and the focus of the study was more on interactions. However, the process proved to be much more useful than expected and led to a number of further insights about the work of the community.

Whereas the consolidated Flow Model shows the interaction between roles, consolidating the Sequence Model demonstrates the structure of a task and the strategies used. Different people will approach work in different ways, and the consolidation of the model helps identify common structures. To consolidate the model, there are six steps:

-

Using the Sequence Models, the researcher needs to identify a number of sequences that address the same task and that would possibly consolidate well. This was done by reading through the sequences, marking with a pencil, and basically coding the sequences.

-

In the selected sequences, activities are identified. The end point for the first activity is marked in each sequence.

-

The triggers are matched across the sequences—these may start at different points.

-

The sequence steps within the first activity are matched, with any omitted steps being added in to make matching easier.

-

The actual steps are abstracted with any breakdowns being added at this point.

-

When the end of the sequence is reached, the intents are added.

Sequences were chosen to show:

-

Collaboration

-

Arranging meetings

-

Having a meeting

-

Co-located management team

-

Distributed WWIT

-

(a) and (b) combined

-

-

Identifying collaboration

-

Noting action to be taken

-

Planning

-

Customer service

-

Clarification

-

Discussion of issues

-

Technical

-

Problem solving/improving

-

Making improvements based on knowledge/expertise/experience

-

Getting help

-

Solving a technical problem

The consolidated Sequence Model for "Identifying Collaboration," along with the notes that were made, is shown in Appendix 6 as an example.

The Artefact Model

I had initially expected that the Artefact Model would perhaps be the most relevant to this study because of its interest in reifications in the form of shared artefacts. This turned out, however, to not be the case, and the consolidation reinforced this point. The aim of consolidating the Artefact Models is to demonstrate how people organise their work and structure it from day to day. This did not work in this case, as the CoP in question does not have a regular, representative weekly routine, and the purpose of the central artefact (the planning document) could not show in its structure how the members organised the work, as it was not that sort of artefact. Holtzblatt and Beyer (1998) explain that people's tasks have similar structure, and therefore the intent and usage of artefacts will also be similar. However the only similar artefacts revealed by the study were:

-

different drafts of the planning document; and

-

two copies of a chat history, one that had been formatted by hand and one that had not been formatted at all.

The selection of Artefact Models is decided by the project focus; for example, if the project is to develop a personal organiser, then the artefacts of interest would have calendar functions. In the research study, the focus was more on how artefacts were used in interactions than on the work itself. Therefore, the emphasis was on a different type of artefact, and it was the Affinity, the Flow Model, and the Sequence Model that proved to be more revealing.

The steps for consolidating the Artefact Models are:

-

Take the Artefact Models and group them according to the roles that they play.

-

Identify common parts in each artefact, and the intent and usage of each part.

-

Identify breakdowns and common structure and usage within each of the common parts.

-

Build a generic artefact to show all the common parts, usage, and intent.

For Step One, the most important artefact within the project focus was felt to be the planning document, and possibly also the online minutes. It did not appear to be beneficial in any way to consolidate the different drafts of the planning document. It also did not seem possible to do Step Two unless it was for the planning document drafts, and this did not seem to be worthwhile. Therefore, I did not do any consolidation of the Artefact Models. I felt it preferable to find a different model to explore the usage of the artefact. This took the form of a time line that was created after later iterations of the planning document (Figure 3, Chapter 6).

The Physical Model

One of the aims of consolidating the Physical Models is to make the researchers aware of limitations imposed by the physical environments. The effectiveness of the models was, however, limited by the fact that they only represented the immediate physical environment. It would have been better had I created a higher level model to demonstrate the limitations imposed on the CoP by the distance to their colleagues in California.

There are only main two steps in consolidating the Physical Models:

-

To separate the models into types of spaces. Beyer and Holtzblatt (1998) note that a set of models will usually represent a whole site or several sites, focusing on the buildings and the relationships between them. Some models may also focus on individuals' spaces and specialised spaces.

-

To catalogue common large structures and organisation. Beyer and Holtzblatt suggest that, for example, telephones, calendars, and address books gathered in one corner of the desk in several models indicate a common theme of communication and co-ordination. Movement is identified if it is relevant to the project focus.

The consolidation phase indicated that the initial Physical Models had not been created well enough and that a better range would have produced more insights in the consolidation. For example, it would have been useful to have created models showing the different sites and the specialised spaces (video suites, AV rooms with polycoms), whereas the models only showed the individual work spaces that were perhaps slightly less relevant to the project focus. The workspaces were all very similar and were indicative of the culture of the organisation in that they were open cubicles in order to encourage informal ad hoc communication. Each cubicle had a range of communication media suggesting the importance of communication and finding people. The movement on the models was only really relevant in cases of co-located work. Although the focus was more aimed at distributed working, the co-located work showed the importance of informal ad-hoc, serendipitous communication. Despite the difficulties posed by the initial error of emphasis in the creation of the models, the process did show two useful insights:

-

It needs to be made easy to locate people in Palo Alto and lower the setup difficulties in talking to them.

-

The individual workspaces are open, so that colleagues can drop in to talk informally. This was an immensely important part of the co-located environment, and it would be beneficial if they could move towards this in the distributed environment. This indicated that a useful avenue to follow would be to increase the awareness of a person's presence at his/her desk, or awareness of his/her availability.

The Cultural Model

I had anticipated that the cultural model would be particularly useful in increasing understanding of the functioning of a CoP in the international environment, as it would record and show the cultural aspects that help sustain or hinder a community.

As with the other models, the Cultural Models are normally created separately, that is, a Cultural Model for each contextual interview. However, during the course of the study so many aspects were being repeated that one single model was created. By the end of the interviews, the result was a Cultural Model that was already well consolidated. Therefore, consolidation was not undertaken as a separate stage for this model. The creation of the Affinity had thrown light on some aspects and to reflect this, some parts of the Affinity were added in to the model for illustrative purposes.

Extra Stages

An important aspect of the Contextual Design method is communication with the customer or, in this case, the people participating in the study.

Adjustments had already been made to reflect the fact that I was working mainly alone rather than as part of a design team, and further adjustments had to be made in this stage. Beyer and Holtzblatt (1998) suggest that the "customers" should be invited to the design team's room to walk the Affinity and for the work models to be used as communication tools.

It was not possible for the members of the group to visit; therefore, a series of propositions were drawn up from the insights created during the process of making the Affinity and consolidating the work models. The propositions and some of the consolidated models were presented to the members of the CoP in two separate meetings in order to elicit feedback and inspire further discussion of the issues. This process was used to confirm, or otherwise, the insights that had been made and to further inform the Affinity. The propositions were designed to encourage discussion, with some of them being made deliberately contentious. The propositions were presented one at a time, but are shown in a list in Appendix 7.

The feedback from the two meetings was then used to further inform the Affinity and the insights that had been extracted from the Affinity and the model consolidation. Linking the categories produced the web of possible relationships shown in Appendix 8.

|

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 77