Section 4.4. Imports

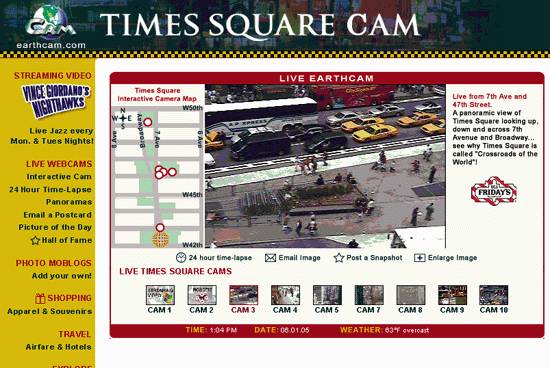

4.4. ImportsAt the soft edges of cyberspace, we're importing vast amounts of information about the real world while simultaneously designing new interfaces for export. It is this great intertwingling of physical and digital that promises a radical departure from the present, for we're talking about nothing less than adding eyes and ears to our digital nervous system. The amount of information on today's Web is insignificant in relation to the oceans of data that will pour into cyberspace through a global network of sensory devices. Change won't come overnight, but our children will inherit a different world. I stole a glimpse at this future a few years ago through the eyes of our eldest daughter, Claire. It was Christmas break, and I finally had a chance to play with my new laptop and wireless network while concurrently entertaining Claire. In the spirit of "embracing the genius of the AND," I decided to try out some webcams, eventually settling on the Live Earthcam at Times Square, shown in Figure 4-13. So, I'm sitting on the couch in Ann Arbor with our two year old, and we're streaming a real-time video feed from New York City, and she loves it! Traffic lights orchestrate an ebb and flow of people and cars, while honking horns punctuate the constant buzz of the big city. For some time, Claire and I are simultaneously in Ann Arbor and New York. This is not the willing suspension of disbelief. It's not like television or the movies. We are experiencing real places in real time. The people are not actors. There is no script. Claire is fascinated by the bright yellow cars, and I explain they are "taxi cabs" and they help people get from place to place. When one appears on screen, she yells "taxi cab, taxi cab." And this experience is seamlessly transferred into the real world where cries of "taxi cab, taxi cab" ring out on trips to the grocery store for the next several years. And each time this occurs, I'm struck by the oddity of a lesson learned at home through a virtual window onto Times Square. A different yet related event occurred in Ann Arbor the following year. A new Blockbuster Video opened less than a mile from our home, and within months of the grand opening, the manager was found brutally murdered inside her own store. We were horrified and worried, particularly since the police had no immediate suspects. Fortunately, the crime was solved within Figure 4-13. Times Square via Live Earthcam days, thanks to a surveillance video camera located across the street which had captured on tape a disgruntled employee entering Blockbuster at the time of the crime. It was the "across the street" part that caught my attention. I hadn't realized the ubiquity and power of surveillance technology, until then. The strange connection between these two stories is, of course, the video camera, which every year grows smaller, cheaper, more powerful, and better networked. From the fun of webcams to the gravity of telemedicine and remote surgery, the camera connects us to distant places and people. Yet it also raises serious concerns about the fate of privacy in a world of nanny cams and ceiling bubbles.

And these are only the visible, outdoor cameras that volunteers were able to identify by wandering the streets. Who knows how many hidden cameras populate the homes, businesses, parking lots, and roads we pass through each day? Not that nighttime is any real obstacle, for infrared cameras provide the ability to see clearly for thousands of feet in total darkness. And then there are those eyes in the sky we call satellites. Constellations of spacecraft hurtling through space, hundreds or thousands of miles above our planet, taking snapshots at sub-meter resolution. We have one of these snapshots hanging on the wall in our living room. It's a picture of our neighborhood taken from space. Our house is clearly visible, and upon close examination, you can pick out the Japanese Zelkova tree we planted in our front yard a few years back. These images can be personal and powerful. They provide a new way to see our world at its best and worst, as Figure 4-14 illustrates. Figure 4-14. Kalatura, Sri Lanka. Receding waters from tsunami (image from DigitalGlobe's QuickBird satellite, December 26, 2004. © 2005 DigitalGlobe Services, Inc.) Of course, eyes work even better when aided by ears, and this potent combination is now being used to stem gun violence on the streets of Chicago and Los Angeles. SENTRI employs microphone surveillance to recognize the sound of a gunshot. The system can precisely locate the point of origin, turn a camera to center the shooter in the viewfinder, and make a 911 call to summon the police.[*] The key innovation of SENTRI is its ability to distinguish a gunshot from other loud noises typical in an urban environment. In fact, this type of automatic pattern recognition is critical in a world where the flow of data far exceeds the limits of human attention. We can't possibly watch all the video or view all the satellite imagery, so we must rely on computers to identify the important events and patterns, converting physical data into symbolic information. This is an area of active research and development, as the following examples illustrate:

Figure 4-15. Traffic conditions in New York from TrafficPulse at http://www.traffic.com/ And here's one of my favorites. An English company is developing a healthcare toilet with embedded sensors that can monitor your diet and detect health problems:

Physical output becomes digital input in this transformation of waste into metadata. Sensors are coming to a loo near you. And this strange business of sensory cyberspace imports has just begun. We can hardly imagine all the weird and wonderful possibilities. |

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 87