Parenting

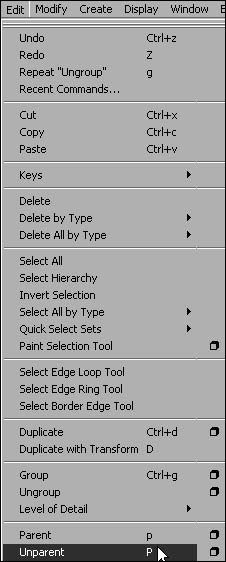

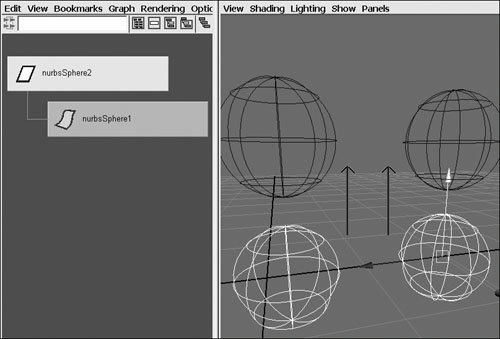

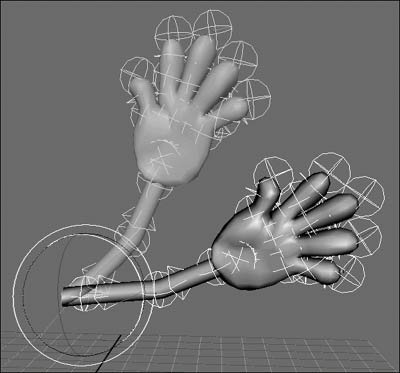

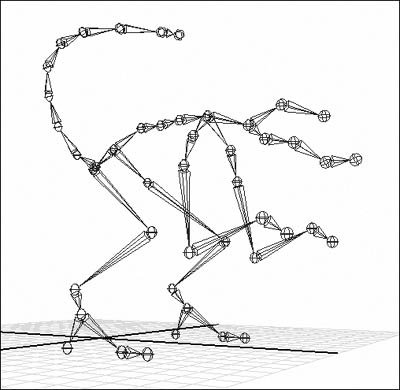

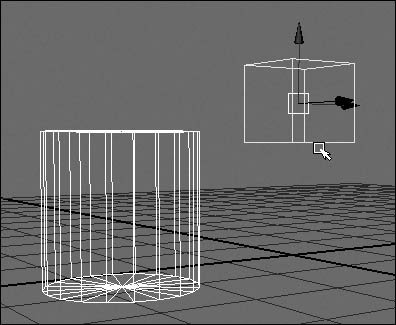

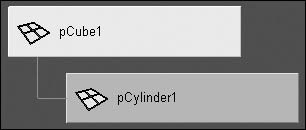

| Parented objects react differently than objects that are grouped. Parented objects have a child-parent relationship. In real life, when a child is holding a parent's hand, the child must go wherever the parent goes (at least in theory). The same is true in 3Dan object that is parented to another object has to follow the other object around (Figure 6.20). This is a direct connection, unlike grouping. When you parent one object to another, no extra node is created. This means the child uses the parent for all its information and treats the parent as its new world space. Figure 6.20. The sphere on the left is parented to the sphere on the right. The sphere on the left will inherit any transformations performed on the sphere on the right. Parenting is very important in setting up skeletons for characters because human bone structure follows a natural parenting chain. Your arm starts at your shoulder blade and continues down, connecting your shoulder to your upper arm to your lower arm to your wrist to your palm to your fingers. When the parts are parented together, a relationship is created that forces the fingers to follow the rest of the arm. In this case, the parent is the upper arm, and its child is the lower arm. The lower arm is the parent of the wrist, which itself is the parent of the palm. Whenever the upper arm is moved, all the children beneath it move, creating the whole arm movement (Figure 6.21). Figure 6.21. The fingers are children of the palm, and the palm is a child of the lower arm. When the upper arm is rotated, all the joints and surfaces below the parent joint follow. The overall relationship of the parts of the skeleton is called a hierarchy (Figure 6.22). A hierarchy determines which objects control other objects. The order of the hierarchy is important to both selecting and translating. Figure 6.22. An entire hierarchy is formed by parenting one bone to another until they're all connected. When you're parenting two objects together, the order in which you select the objects is very important. The second object you select becomes a parent of the first object selected. Once it's parented, the child follows the parent's translations. To parent two objects together:

To unparent objects:

|

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 185

Tip

Tip