Just-in-Time

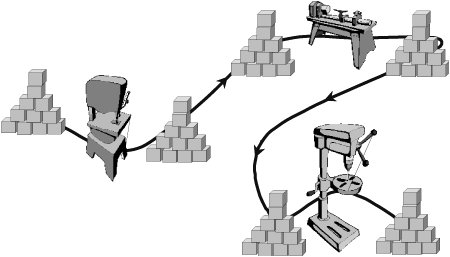

| The Toyota Production System was largely ignored, even in Japan, until the oil crisis of 1973, because companies were growing quickly and they could sell everything they made. But the economic slowdown triggered by the oil crisis sorted out excellent companies from mediocre ones, and Toyota emerged from the crisis quickly. The Toyota Production System was studied by other Japanese companies and many of its features were adopted. Within a decade America and Europe began to feel serious competition from Japan. For example, I (Mary) was working in a video cassette plant in the early '80s when Japanese competitors entered the market with dramatically low pricing. Investigation showed that the Japanese companies were using a new approach called Just-in-Time, so my plant studied and adopted Just-in-Time to remain competitive. The picture that we used at our plant to depict Just-in-Time manufacturing is shown in Figure 1.1. Figure 1.1. Lower inventory to surface problems Inventory is the water level in a stream, and when the water level is high, a lot of big rocks lurking under the water are hidden. If you lower the water level, the big rocks begin to surface. At that point, you have to clear the rock out of the way, or your boat will crash into them. As the big rocks are removed, you can lower inventory level some more, find more rocks, clear them out of the stream, and keep on going until there are just pebbles left. Why not just keep the inventory high and ignore the rocks? Well, the rocks are things like defects that creep into the product without being detected, processes that drift out of control, finished goods that people aren't going to buy before the shelf life expires, an inventory tracking system that keeps on losing track of inventorythings like that. The rocks are hidden waste that is costing you a lot of moneyyou just don't know it unless you lower the inventory level. A key lesson from our Just-in-Time initiative was that we had to stop trying to maximize local efficiencies. We had a lot of expensive machines, so we thought we should run them each at maximum productivity. But that only increased our inventory, because a pile of inventory built up at the input to each machine to keep it running, and at the output from each machine as it merrily produced product that had nowhere to go. When we implemented Just-in-Time, the piles of inventory disappeared, and we were surprised to discover that the overall performance of the plant actually increased when we did not try to run our machines at maximum utilization (see Figure 1.2). Figure 1.2. Stop trying to maximize local efficiencies.

When we decided to move our plant to Just-in-Time, there were few consultants around to tell us what to do, so we had to figure it out ourselves. We created a simulation by covering a huge conference table with a big sheet of brown paper, then drawing the plant processes on the paper. We made "kanban cards" by writing various inventory types on strips cut from index cards. We put an inventory strip into a coffee cup andviola!that cup became a cart full of the indicated inventory. (See Figure 1.3.) Then we printed a week's packing orders and simulated a pull system by attempting to fill the orders, using the cups and the big sheet of paper like a game board. When a cup of inventory was packed, the inventory strip (kanban card) was moved to the previous process, which used it as a signal to make more of that material.[8]

Figure 1.3. Coffee cups simulating inventory carts with kanban cards With this manual simulation we showed the concept of a pull system to the production managers, then the general supervisors, then the shift supervisors. Finally, the shift supervisors ran through the simulation with every worker in their area. Each work area was asked to figure out the details of how to make this new pull system work in their environment. It took some months of detailed preparation, but finally everything was ready. We held our collective breath as we changed the whole plant over to a pull system in one weekend. Computerized scheduling was turned off, its place taken by manual scheduling via kanban cards. Our Just-in-Time system was an immediate and smashing success, largely because the details were designed by the workers, who therefore knew how to iron out the small glitches and continually improve the process. |

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 89