Section 8.6. Case Study: A Two-Player Game Hierarchy

8.6. Case Study: A Two-Player Game HierarchyIn this section we will redesign our OneRowNim game to fit within a hierarchy of classes of two-player games. There are many games that characteristically involve two players: checkers, chess, tic-tac-toe, guessing games, and so forth. However, there are also many games that involve just one player: blackjack, solitaire, and others. There are also games that involve two or more players, such as many card games. Thus, our redesign of OneRowNim as part of a two-player game hierarchy will not be our last effort to design a hierarchy of game-playing classes. We will certainly redesign things as we learn new Java language constructs and as we try to extend our game library to other kinds of games. This case study will illustrate how we can apply inheritance and polymorphism, as well as other object-oriented design principles. The justification for revising OneRowNim at this point is to make it easier to design and develop other two-player games. As we have seen, one characteristic of class hierarchies is that more general attributes and methods are defined in top-level classes. As one proceeds down the hierarchy, the methods and attributes become more specialized. Creating a subclass is a matter of specializing a given class. 8.6.1. Design GoalsOne of our design goals is to revise the OneRowNim game so that it fits into a hierarchy of two-player games. One way to do this is to generalize the OneRowNim game by creating a superclass that contains those attributes and methods that are common to all two-player games. The superclass will define the most general and generic elements of two-player games. All two-player games, including OneRowNim, will be defined as subclasses of this top-level superclass and will inherit and possibly override its public and protected variables and methods. Also, our top-level class will contain certain abstract methods, whose implementations will be given in OneRowNim and other subclasses.

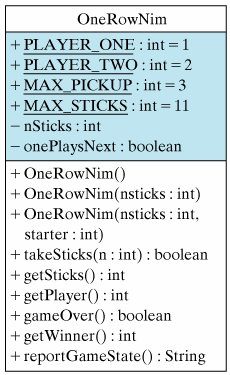

Generic superclass A second goal is to design a class hierarchy that makes it possible for computers to play the game, as well as human users. Thus, for a given two-player game, it should be possible for two humans to play each other, or for two computers to play each other, or for a human to play against a computer. This design goal will require that our design exhibit a certain amount of flexibility. As we shall see, this is a situation in which Java interfaces will come in handy. Another important goal is to design a two-player game hierarchy that can easily be used with a variety of different user interfaces, including command-line interfaces and GUIs. To handle this feature, we will develop Java interfaces to serve as interfaces between our two-player games and various user interfaces. 8.6.2. Designing the TwoPlayerGame ClassTo begin revising the design of the OneRowNim game, we first need to design a top-level class, which we will call the TwoPlayerGame class. What variables and methods belong in this class? One way to answer this question is to generalize our current version of OneRowNim by moving any variables and methods that apply to all two-player games up to the TwoPlayerGame class. All subclasses of TwoPlayerGamewhich includes the OneRowNim classwould inherit these elements. Figure 8.18 shows the current design of OneRowNim. Figure 8.18. The current OneRowNim class. What variables and methods should we move up to the TwoPlayerGame class? Clearly, the class constants, PLAYER_ONE and PLAYER_TWO, apply to all two-player games. These should be moved up. On the other hand, the MAX_PICKUP and MAX_STICKS constants apply just to the OneRowNim game. They should remain in the OneRowNim class. The nSticks instance variable is a variable that only applies to the OneRowNim game but not to other two-player games. It should stay in the OneRowNim class. On the other hand, the onePlaysNext variable applies to all two-player games, so we will move it up to the TwoPlayerGame class. Because constructors are not inherited, all of the constructor methods will remain in the OneRowNim class. The instance methods, takeSticks() and getSticks(), are specific to OneRowNim, so they should remain there. However, the other methods, getPlayer(), gameOver(), getWinner(), and reportGameState(), are methods that would be useful to all two-player games. Therefore these methods should be moved up to the superclass. Of course, while these methods can be defined in the superclass, some of them can only be implemented in subclasses. For example, the reportGameState() method reports the current state of the game, so it has to be implemented in OneRowNim. Similarly, the getWinner() method defines how the winner of the game is determined, a definition that can only occur in the subclass. Every two-player game needs methods such as these. Therefore, we will define these methods as abstract methods in the superclass. The intention is that TwoPlayerGame subclasses will provide game-specific implementations for these methods.

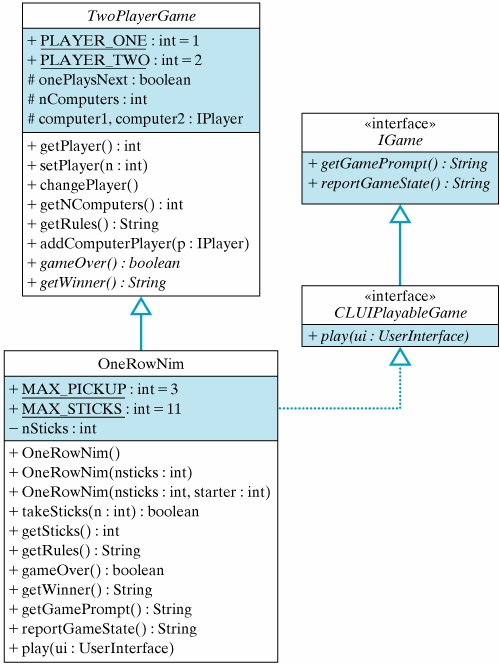

Constructors are not inherited Given these considerations, we come up with the design shown in Figure 8.19. The design shown in this figure is much more complex than the designs used in earlier chapters. However, the complexity comes from combining ideas already discussed in previous sections of this chapter, so don't be put off by it. Figure 8.19. TwoPlayerGame is the superclass for OneRowNim and other two-player games. To begin with, note that we have introduced two Java interfaces into our design in addition to the TwoPlayerGame superclass. As we will show, these interfaces lead to a more flexible design and one that can easily be extended to incorporate new two-player games. Let's take each element of this design separately. 8.6.3. The TwoPlayerGame SuperclassAs we have stated, the purpose of the TwoPlayerGame class is to serve as the superclass for all two-player games. Therefore, it should define the variables and methods shared by two-player games. The PLAYER_ONE, PLAYER_TWO, and onePlaysNext variables and the getPlayer(), setPlayer(), and changePlayer() methods have been moved up from the OneRowNim class. Clearly, these variables and methods apply to all two-player games. Note that we have also added three new variables, nComputers, computer1, computer2, and their corresponding methods, getNComputers() and addComputerPlayer(). We will use these elements to give our games the capability to be played by computer programs. Because we want all of our two-player games to have this capability, we define these variables and methods in the superclass rather than in OneRowNim and subclasses of TwoPlayerGame. Note that the computer1 and computer2 variables are declared to be of type IPlayer. IPlayer is an interface containing a single method declaration, the makeAMove() method: public interface IPlayer { public String makeAMove(String prompt); } Why do we use an interface here rather than some type of game-playing object? This is a good design question. Using an interface here makes our design more flexible and extensible because it frees us from having to know the names of the classes that implement the makeAMove() method. The variables computer1 and computer2 will be assigned objects that implement IPlayer via the addComputerPlayer() method.

Game-dependent algorithms The algorithms used in the various implementations of makeAMove() are game-dependentthey depend on the particular game being played. It would be impossible to define a game playing object that would suffice for all two-player games. Instead, if we want an object that plays OneRowNim, we would define a OneRowNimPlayer and have it implement the IPlayer interface. Similarly, if we want an object that plays checkers, we would define a CheckersPlayer and have it implement the IPlayer interface. By using an interface here, our TwoPlayerGame hierarchy can deal with a wide range of differently named objects that play games, as long as they implement the IPlayer interface. Using the IPlayer interface adds flexibility to our game hierarchy and makes it easier to extend it to new, yet undefined, classes. We will discuss the details of how to design a game player in Section 8.6.7.

The IPlayer interface Turning now to the methods defined in TwoPlayerGame, we have already seen implementations of getPlayer(), setPlayer(), and changePlayer() in the OneRowNim class. We will just move those implementations up to the superclass. The getNComputers() method is the assessor method for the nComputers variable, and its implementation is routine. The addComputerPlayer() method adds a computer player to the game. Its implementation is as follows: public void addComputerPlayer(IPlayer player) { if (nComputers == 0) computer2 = player; else if (nComputers == 1) computer1 = player; else return; // No more than 2 players ++nComputers; } As we noted earlier, the classes that play the various TwoPlayerGames must implement the IPlayer interface. The parameter for this method is of type IPlayer. The algorithm we use checks the current value of nComputers. If it is 0, which means that this is the first IPlayer added to the game, the player is assigned to computer2. This allows the human user to be associated with PLAYERONE if this is a game between a computer and a human user. If nComputers equals 1, which means that we are adding a second IPlayer to the game, we assign that player to computer1. In either of these cases, we increment nComputers. Note what happens if nComputers is neither 1 nor 2. In that case, we simply return without adding the IPlayer to the game and without incrementing nComputers. This, in effect, limits the number of IPlayers to two. (A more sophisticated design would throw an exception to report an error. but we will leave that for a subsequent chapter.) The addComputerPlayer() method is used to initialize a game after it is first created. If this method is not called, the default assumption is that nComputers equals zero and that computer1 and computer2 are both null. Here's an example of how it could be used: OneRowNim nim = new OneRowNim(11); // 11 sticks nim.add(new NimPlayer(nim)); // 2 computer players nim.add(new NimPlayerBad(nim)); Note that the NimPlayer() constructor takes a reference to the game as its argument. Clearly, our design should not assume that the names of the IPlayer objects would be known to the TwoPlayerGame superclass. This method allows the objects to be passed in at runtime. We will discuss the details of NimPlayerBad in Section 8.6.7. The getrules() method is a new method whose purpose is to return a string that describes the rules of the particular game. This method is implemented in the TwoPlayerGame class with the intention that it will be overridden in the various subclasses. For example, its implementation in TwoPlayerGame is: public String getRules() { return "The rules of this game are: "; }

Overriding a method and its redefinition in OneRowNim is: public String getRules() { return "\n*** The Rules of One Row Nim ***\n" + "(1) A number of sticks between 7 and " + MAX_STICKS + " is chosen.\n" + "(2) Two players alternate making moves.\n" + "(3) A move consists of subtracting between 1 and\n\t" + MAX_PICKUP + " sticks from the current number of sticks.\n" + "(4) A player who cannot leave a positive\n\t" + " number of sticks for the other player loses.\n"; } The idea is that each TwoPlayerGame subclass will take responsibility for specifying its own set of rules in a form that can be displayed to the user. You might recognize that defining geTRules() in the superclass and allowing it to be overridden in the subclasses is a form of polymorphism. It follows the design of the toString() method, which we discussed earlier. This design will allow us to use code that takes the following form: TwoPlayerGame game = new OneRowNim(); System.out.println(game.getRules());

Polymorphism In this example the call to getrules() is polymorphic. The dynamic-binding mechanism is used to invoke the getrules() method defined in the OneRowNim class. The remaining methods in TwoPlayerGame are defined abstractly. The gameOver() and getWinner() methods are both game-dependent methods. That is, the details of their implementations depend on the particular TwoPlayerGame subclass in which they are implemented. This is good example of how abstract methods should be used in designing a class hierarchy. We give abstract definitions in the superclass and leave the detailed implementations up to the individual subclasses. This allows the different subclasses to tailor the implementations to their particular needs, while allowing all subclasses to share a common signature for these tasks. This enables us to use polymorphism to create flexible, extensible class hierarchies. Figure 8.20 shows the complete implementation of the abstract TwoPlayerGame class. We have already discussed the most important details of its implementation. Figure 8.20. The TwoPlayerGame class |

public abstract class TwoPlayerGame { public static final int PLAYER_ONE = 1; public static final int PLAYER_TWO = 2; protected boolean onePlaysNext = true; protected int nComputers = 0; // How many computers // Computers are IPlayers protected IPlayer computer1, computer2; public void setPlayer(int starter) { if (starter == PLAYER_TWO) onePlaysNext = false; else onePlaysNext = true; } // setPlayer() public int getPlayer() { if (onePlaysNext) return PLAYER_ONE; else return PLAYER_TWO; } // getPlayer() public void changePlayer() { onePlaysNext = !onePlaysNext; } // changePlayer() public int getNComputers() { return nComputers; } // getNComputers() public String getRules() { return "The rules of this game are: "; } // getRules() public void addComputerPlayer(IPlayer player) { if (nComputers == 0) computer2 = player; else if (nComputers == 1) computer1 = player; else return; // No more than 2 players ++nComputers; } // addComputerPlayer() public abstract boolean gameOver(); // Abstract Methods public abstract String getWinner(); } // TwoPlayerGame class |

Effective Design: Abstract Methods

Abstract methods allow you to give general definitions in the superclass and leave the implementation details to the different subclasses. |

8.6.4. The CLUIPlayableGame Interface

We turn now to the two interfaces shown in Figure 8.19. Taken together, the purpose of these interfaces is to create a connection between any two-player game and a command-line user interface (CLUI). The interfaces provide method signatures for the methods that will implement the details of the interaction between a TwoPlayerGame and a UserInterface. Because the details of this interaction vary from game to game, it is best to leave the implementation of these methods to the games themselves.

Note that CLUIPlayableGame extends the IGame interface. The IGame interface contains two methods that are used to define a standard form of communication between the CLUI and the game. The getGamePrompt() method defines the prompt used to signal the user for a move of some kindfor example, "How many sticks do you take (1, 2, or 3)?" And the reportGameState() method defines how the game will report its current statefor example, "There are 11 sticks remaining." CLUIPlayableGame adds the play() method to these two methods. As we will see shortly, the play() method contains the code that will control the playing of the game.

Extending an interface

The source code for these interfaces is very simple:

public interface CLUIPlayableGame extends IGame { public abstract void play(UserInterface ui); } public interface IGame { public String getGamePrompt(); public String reportGameState(); } // IGame

Note that the CLUIPlayableGame interface extends the IGame interface. A CLUIPlayableGame is a game that can be played through a CLUI. The purpose of its play() method is to contain the game-dependent control loop that determines how the game is played via a user interface (UI). In pseudocode, a typical control loop for a game would look something like the following:

Initialize the game. While the game is not over Report the current state of the game via the UI. Prompt the user (or the computer) to make a move via the UI. Get the user's move via the UI. Make the move. Change to the other player.

The play loop sets up an interaction between the game and the UI. The UserInterface parameter allows the game to connect directly to a particular UI. To allow us to play our games through a variety of UIs, we define UserInterface as the following Java interface:

public interface UserInterface { public String getUserInput(); public void report(String s); public void prompt(String s); }

Any object that implements these three methods can serve as a UI for one of our TwoPlayerGames. This is another example of the flexibility of using interfaces in object-oriented design.

To illustrate how we use UserInterface, let's attach it to our KeyboardReader class, thereby letting a KeyboardReader serve as a CLUI for TwoPlayerGames. We do this simply by implementing this interface in the KeyboardReader class, as follows:

public class KeyboardReader implements UserInterface

As it turns out, the three methods listed in UserInterface match three of the methods in the current version of KeyboardReader. This is no accident. The design of UserInterface was arrived at by identifying the minimal number of methods in KeyboardReader that were needed to interact with a TwoPlayerGame.

Effective Design: Flexibility of Java Interfaces

A Java interface provides a means of associating useful methods with a variety of different types of objects, leading to a more flexible object-oriented design. |

The benefit of defining the parameter more generally as a UserInterface instead of as a KeyboardReader is that we will eventually want to allow our games to be played via other kinds of command-line interfaces. For example, we might later define an Internet-based CLUI that could be used to play OneRowNim among users on the Internet. This kind of extensibilitythe ability to create new kinds of UIs and use them with TwoPlayerGamesis another important design feature of Java interfaces.

Generality principle

Effective Design: Extensibility and Java Interfaces

Using interfaces to define useful method signatures increases the extensibility of a class hierarchy. |

As Figure 8.19 shows, OneRowNim implements the CLUIPlayableGame interface, which means it must supply implementations of all three abstract methods: play(), getGamePrompt(), and reportGameState().

8.6.5. Object-Oriented Design: Interfaces or Abstract Classes?

Why are these methods defined in interfaces? Couldn't we just as easily define them in the TwoPlayerGame class and use inheritance to extend them to the various game subclasses? After all, isn't the net result the same, namely, that OneRowNim must implement all three methods.

These are very good design questions, exactly the kinds of questions one should ask when designing a class hierarchy of any sort. As we pointed out in the Animal example earlier in the chapter, you can get the same functionality from an abstract interface and an abstract superclass method. When should we put the abstract method in the superclass, and when does it belong in an interface? A very good discussion of these and related object-oriented design issues is available in Java Design, 2nd Edition, by Peter Coad and Mark Mayfield (Yourdan Press, 1999). Our discussion of these issues follows many of the guidelines suggested by Coad and Mayfield.

Interfaces vs. abstract methods

We have already seen that using Java interfaces increases the flexibility and extensibility of a design. Methods defined in an interface exist independently of a particular class hierarchy. By their very nature, interfaces can be attached to any class, and this makes them very flexible to use.

Flexibility of interfaces

Another useful guideline for answering this question is that the superclass should contain the basic common attributes and methods that define a certain type of object. It should not necessarily contain methods that define certain roles that the object plays. For example, the gameOver() and getWinner() methods are fundamental parts of the definition of a TwoPlayerGame. One cannot define a game without defining these methods. By contrast, methods such as play(), getGamePrompt(), and reportGameState() are important for playing the game but they do not contribute in the same way to the game's definition. Thus these methods are best put into an interface. Therefore, one important design guideline is:

Effective Design: Abstract Methods

Methods defined abstractly in a superclass should contribute in a fundamental way to the basic definition of that type of object, not merely to one of its roles or its functionality. |

8.6.6. The Revised OneRowNim Class

Figure 8.21 provides a listing of the revised OneRowNim class, one that fits into the TwoPlayerGame class hierarchy. Our discussion in this section will focus on the features of the game that are new or revised.

Figure 8.21. The revised OneRowNim class, Part I. (This item is displayed on page 385 in the print version)

public class OneRowNim extends TwoPlayerGame implements CLUIPlayableGame { public static final int MAX_PICKUP = 3; public static final int MAX_STICKS = 11; private int nSticks = MAX_STICKS; public OneRowNim() { } // Constructors public OneRowNim(int sticks) { nSticks = sticks; } // OneRowNim() public OneRowNim(int sticks, int starter) { nSticks = sticks; setPlayer(starter); } // OneRowNim() public boolean takeSticks(int num) { if (num < 1 || num > MAX_PICKUP || num > nSticks) return false; // Error else // Valid move { nSticks = nSticks - num; return true; } // else } // takeSticks() public int getSticks() { return nSticks; } // getSticks() public String getRules() { return "\n*** The Rules of One Row Nim ***\n" + "(1) A number of sticks between 7 and " + MAX_STICKS + " is chosen.\n" + "(2) Two players alternate making moves.\n" + "(3) A move consists of subtracting between 1 and\n\t" + MAX_PICKUP + " sticks from the current number of sticks.\n" + "(4) A player who cannot leave a positive\n\t" + " number of sticks for the other player loses.\n"; } // getRules() public boolean gameOver() { /*** From TwoPlayerGame */ return (nSticks <= 0); } // gameOver() public String getWinner() { /*** From TwoPlayerGame */ if (gameOver()) //{ return "" + getPlayer() + " Nice game."; return "The game is not over yet."; // Game is not over } // getWinner() |

The gameOver() and getWinner() methods, which are nowinherited from the TwoPlayerGame superclass, are virtually the same as in the previous version. One small change is that getWinner() now returns a String instead of an int. This makes the method more generally useful as a way of identifying the winner for all TwoPlayerGames.

Similarly, the getGamePrompt() and reportGameState() methods merely encapsulate functionality that was present in the earlier version of the game. In our earlier version the prompts to the user were generated directly by the main program. By encapsulating this information in an inherited method, we make it more generally useful to all TwoPlayerGames.

Inheritance and generality

The major change to OneRowNim comes in the play() method, which controls the playing of OneRowNim (Fig. 8.22). Because this version of the game incorporates computer players, the play loop is a bit more complex than in earlier versions of the game. The basic idea is still the same: The method loops until the game is over. On each iteration of the loop, one or the other of the two players, PLAYER_ONE or PLAYER_TWO, takes a turn making a movethat is, deciding how many sticks to pick up. If the move is a legal move, then it becomes the other player's turn.

Figure 8.22. The revised OneRowNim class, Part II. (This item is displayed on page 386 in the print version)

/** From CLUIPlayableGame */ public String getGamePrompt() { return "\nYou can pick up between 1 and " + Math.min(MAX_PICKUP,nSticks) + " : "; } // getGamePrompt() public String reportGameState() { if (!gameOver()) return ("\nSticks left: " + getSticks() + " Who's turn: Player " + getPlayer()); else return ("\nSticks left: " + getSticks() + " Game over! Winner is Player " + getWinner() +"\n"); } // reportGameState() public void play(UserInterface ui) { // From CLUIPlayableGame interface int sticks = 0; ui.report(getRules()); if (computer1 != null) ui.report("\nPlayer 1 is a " + computer1.toString()); if (computer2 != null) ui.report("\nPlayer 2 is a " + computer2.toString()); while(!gameOver()) { IPlayer computer = null; // Assume no computers ui.report(reportGameState()); switch(getPlayer()) { case PLAYER_ONE: // Player 1's turn computer = computer1; break; case PLAYER_TWO: // Player 2's turn computer = computer2; break; } // cases if (computer != null) { // If computer's turn sticks = Integer.parseInt(computer.makeAMove("")); ui.report(computer.toString() + " takes " + sticks + " sticks.\n"); } else { // otherwise, user's turn ui.prompt(getGamePrompt()); sticks = Integer.parseInt(ui.getUserInput()); // Get user's move } if (takeSticks(sticks)) // If a legal move changePlayer(); } // while ui.report(reportGameState()); // The game is now over } // play() } // OneRowNim class |

Let's look now at how the code decides whether it is a computer's turn to move or a human player's turn. Note that at the beginning of the while loop, it sets the computer variable to null. It then assigns computer a value of either computer1 or computer2, depending on whose turn it is. But recall that one or both of these variables may be null, depending on how many computers are playing the game. If there are no computers playing the game, then both variables will be null. If only one computer is playing, then computer1 will be null. This is determined during initialization of the game, when the addComputerPlayer() is called. (See above.)

In the code following the switch statement, if computer is not null, then we call computer.makeAMove(). As we know, the makeAMove() method is part of the IPlayer interface. The makeAMove() method takes a String parameter that is meant to serve as a prompt, and returns a String that is meant to represent the IPlayer's move:

public interface IPlayer { public String makeAMove(String prompt); }

In OneRowNim the "move" is an integer, representing the number of sticks the player picks. Therefore, in play() OneRowNim has to convert the String into an int, which represents the number of sticks the IPlayer picks up.

On the other hand, if computer is null, this means that it is a human user's turn to play. In this case, play() calls ui.getUserInput(), employing the user interface to input a value from the keyboard. The user's input must also be converted from String to int. Once the value of sticks is set, either from the user or from the IPlayer, the play() method calls takeSticks(). If the move is legal, then it changes whose turn it is, and the loop repeats.

There are a couple of important points about the design of the play() method. First, the play() method has to know what to do with the input it receives from the user or the IPlayer. This is game-dependent knowledge. The user is inputting the number of sticks to take in OneRowNim. For a tic-tac-toe game, the "move" might represent a square on the tic-tac-toe board. This suggests that play() is a method that should be implemented in OneRowNim, as it is here, because OneRowNim encapsulates the knowledge of how to play the One-Row Nim game.

Encapsulation of game-dependent knowledge

The second point is that the method call computer.makeAMove() is another example of polymorphism at work. The play() method does not know what type of object the computer is, other than that it is an IPlayerthat is, an object that implements the IPlayer interface. As we will show in the next section, the OneRowNim game can be played by two different IPlayers: one named NimPlayer and another named NimPlayerBad. Each has its own game-playing strategy, as implemented by its own version of the makeAMove() method. Java uses dynamic binding to decide which version of makeAMove() to invoke depending on the type of IPlayer whose turn it is. Thus, by defining different IPlayers with different makeAMove() methods, this use of polymorphism makes it possible to test different game playing strategies against each other.

Polymorphism

8.6.7. The IPlayer Interface

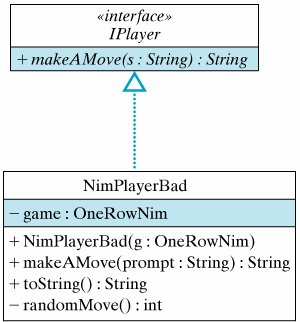

The last element of our design is the IPlayer interface, which, as we just saw, consists of the makeAMove() method. To see how we use this interface, let's design a class to play the game of OneRowNim. We will call the class NimPlayerBad and give it a very weak playing strategy. For each move it will pick a random number between 1 and 3, or between 1 and the total number of sticks left, if there are fewer than three sticks. (We will leave the task of defining NimPlayer, a good player, as an exercise.)

As an implementer of the IPlayer interface, NimPlayerBad will implement the makeAMove() method. This method will contain NimPlayerBad's strategy (algorithm) for playing the game. The result of this strategy will be the number of sticks the player will pick up.

What other elements (variables and methods) will a NimPlayerBad need? Clearly, in order to play OneRowNim, the player must know the rules and the current state of the game. The best way to achieve this is to give the Nim player a reference to the OneRowNim game. Then it can call getSticks() to determine how many sticks are left, and it can use other public elements of the OneRowNim game. Thus, we will have a variable of type OneRowNim, and we will assign it a value in a constructor method.

Figure 8.23 shows the design of NimPlayerBad. Note that we have added an implementation of the toString() method. This will be used to give a string representation of NimPlayerBad. Also note that we have added a private helper method named randomMove(), which will generate an appropriate random number of sticks as the player's move.

Figure 8.23. Design of the NimPlayerBad class.

The implementation of NimPlayerBad is shown in Figure 8.24. The makeAMove() method converts randomMove() to a String and returns it, leaving it up to OneRowNim, the calling object, to convert that move back into an int. Recall the statement in OneRowNim where makeAMove() is invoked:

sticks = Integer.parseInt(computer.makeAMove(""));Figure 8.24. The NimPlayerBad class.

public class NimPlayerBad implements IPlayer { private OneRowNim game; public NimPlayerBad (OneRowNim game) { this.game = game; } // NimPlayerBad() public String makeAMove(String prompt) { return "" + randomMove(); } // makeAMove() private int randomMove() { int sticksLeft = game.getSticks(); return 1 + (int)(Math.random() * Math.min(sticksLeft, game.MAX_PICKUP)); } // randomMove() public String toString() { String className = this.getClass().toString(); // Gets 'class NimPlayerBad' return className.substring(5); // Cut off the word 'class' } // toString() } // NimPlayerBad class |

In this context, the computer variable, which is of type IPlayer, is bound to a NimPlayerBad object. In order for this interaction between the game and a player to work, the OneRowNim object must know what type of data is being returned by NimPlayerBad. This is a perfect use for a Java interface that specifies the signature of makeAMove() without committing to any particular implementation of the method. Thus, the association between OneRowNim and IPlayer provides a flexible and effective model for this type of interaction.

Effective Design: Interface Associations

Java interfaces provide a flexible way to set up associations between two different types of objects. |

Finally, note the details of the randomMove() and toString() methods. The only new thing here is the use of the getClass() method in toString(). This is a method that is defined in the Object class and inherited by all Java objects. It returns a String of the form "class X" where X is the name of the object's class. Note here that we are removing the word "class" from the string before returning the class name. This allows our IPlayer objects to report what type of players they are, as in the following statement from OneRowNim:

ui.report("\nPlayer 1 is a " + computer1.toString()); If computer1 is a NimPlayerBad, it would report "Player1 is a NimPlayerBad".

Self-Study Exercises

| Exercise 8.13 | Define a class NimPlayer that plays the optimal strategy for OneRowNim. This strategy was described in Chapter 5. |

8.6.8. Playing OneRowNim

Let's now write a main() method to play OneRowNim:

public static void main(String args[]) { KeyboardReader kb = new KeyboardReader(); OneRowNim game = new OneRowNim(); kb.prompt("How many computers are playing, 0, 1, or 2? "); int m = kb.getKeyboardInteger(); for (int k = 0; k < m; k++) { kb.prompt("What type of player, " + "NimPlayerBad = 1, or NimPlayer = 2 ? "); int choice = kb.getKeyboardInteger(); if (choice == 1) { IPlayer computer = new NimPlayerBad(game); game.addComputerPlayer(computer); } else { IPlayer computer = new NimPlayer(game); game.addComputerPlayer(computer); } } game.play(kb); } // main()

After creating a KeyboardReader and then creating an instance of OneRowNim, we prompt the user to determine how many computers are playing. We then repeatedly prompt the user to identify the names of the IPlayer and use the addComputerPlayer() method to initialize the game. Finally, we get the game started by invoking the play() method, passing it a reference to the KeyboardReader, our UserInterface.

In this example we have declared a OneRowNim variable to represent the game. This is not the only way to do things. For example, suppose we wanted to write a main() method that could be used to play a variety of different TwoPlayerGames. Can we make this code more general? That is, can we rewrite it to work with any TwoPlayerGame?

Generality

A OneRowNim object is a TwoPlayerGame by virtue of inheritance, and it is also a CLUIPlayableGame by virtue of implementing that interface. Therefore, we can use either of these types to represent the game. Thus, one alternative way of coding this is as follows:

TwoPlayerGame game = new OneRowNim(); ... IPlayer computer = new NimPlayer((OneRowNim)game); ... ((CLUIPlayableGame)game).play(kb);

Here we use a TwoPlayerGame variable to represent the game. However, note that we now have to use a cast expression, (CLUIPlayableGame), in order to call the play() method. If we don't cast game in this way, Java will generate the following syntax error:

OneRowNim.java:126: cannot resolve symbol symbol : method play (KeyboardReader) location: class TwoPlayerGame game.play(kb); ^ The reason for this error is that play() is not a method in the TwoPlayerGame class, so the compiler cannot find the play() method. By using the cast expression, we are telling the compiler to consider game to be a CLUIPlayableGame. That way it will find the play() method. Of course, the object assigned to nim must actually implement the CLUIPlayableGame interface in order for this to work at runtime. We also need a cast operation in the NimPlayer() constructor in order to make the argument (computer) compatible with that method's parameter.

Another alternative for the main() method would be the following:

CLUIPlayableGame game = new OneRowNim(); ... IPlayer computer = new NimPlayer((OneRowNim)game); ((TwoPlayerGame)game).addComputerPlayer(computer); ... game.play(kb);

By representing the game as a CLUIPlayableGame variable, we don't need the cast expression to call play(), but we do need a different cast expression, (TwoPlayerGame), to invoke addComputerPlayer(). Again, the reason is that the compiler cannot find the addComputerPlayer() method in the CLUIPlayableGame interface, so we must tell it to consider game as a TwoPlayerGame, which of course it is. We still need the cast operation for the call to the NimPlayer() constructor.

All three of the code options that we have considered will generate something like the interactive session shown in Figure 8.25 for a game in which two IPlayers play each other.

Figure 8.25. A typical run of OneRowNim using a command-line user interface. (This item is displayed on page 391 in the print version)

How many computers are playing, 0, 1, or 2? 2 *** The Rules of One Row Nim *** (1) A number of sticks between 7 and 11 is chosen. (2) Two players alternate making moves. (3) A move consists of subtracting between 1 and 3 sticks from the current number of sticks. (4) A player who cannot leave a positive number of sticks for the other player loses. Player 1 is a NimPlayerBad Player 2 is a NimPlayer Sticks left: 11 Who's turn: Player 1 NimPlayerBad takes 2 sticks. Sticks left: 9 Who's turn: Player 2 NimPlayer takes 1 sticks. Sticks left: 8 Who's turn: Player 1 NimPlayerBad takes 2 sticks. Sticks left: 6 Who's turn: Player 2 NimPlayer takes 1 sticks. Sticks left: 5 Who's turn: Player 1 NimPlayerBad takes 3 sticks. Sticks left: 2 Who's turn: Player 2 NimPlayer takes 1 sticks. Sticks left: 1 Who's turn: Player 1 NimPlayerBad takes 1 sticks. Sticks left: 0 Game over! Winner is Player 2 Nice game. |

Given our object-oriented design for the TwoPlayerGame hierarchy, we can now write generalized code that can play any TwoPlayerGame that implements the CLUIPlayableGame interface. We will give a specific example of this in the next section.

8.6.9. Extending the TwoPlayerGame Hierarchy

Now that we have described the design and the details of the TwoPlayerGame class hierarchy, let's use it to develop a new game. If we've gotten the design right, developing new two-player games and adding them to the hierarchy should be much simpler than developing them from scratch.

The new game is a guessing game in which the two players take turns guessing a secret word. The secret word will be generated randomly from a collection of words maintained by the game object. The letters of the word will be hidden with question marks, as in "????????". On each turn a player guesses a letter. If the letter is in the secret word, it replaces one or more question marks, as in "??????E?". A player continues to guess until an incorrect guess is made and then it becomes the other player's turn. Of course, we want to develop a version of this game that can be played either by two humans, or by one human against a computerthat is, against an IPlayer, or by two different IPlayers.

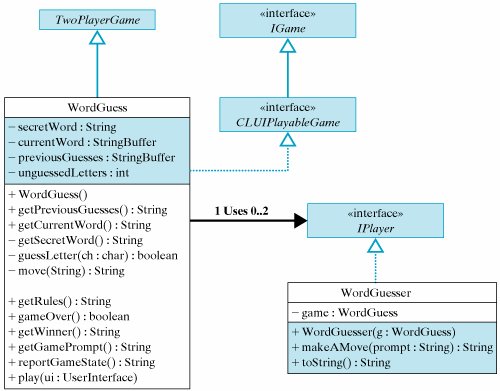

Let's call the game class WordGuess. Following the design of OneRowNim, we get the design shown in Figure 8.26. The WordGuess class extends the TwoPlayerGame class and implements the CLUIPlayableGame interface. We don't show the details of the interfaces and the TwoPlayerGame class, as these have not changed. Also, following the design of NimPlayerBad, the WordGuesser class implements the IPlayer interface. Note how we show the association between WordGuess and zero or more IPlayers. A WordGuess uses between zero and two instances of IPlayers, which in this game are implemented as WordGuessers.

Figure 8.26. Design of the WordGuess class as part of TwoPlayerGame hierarchy. (This item is displayed on page 391 in the print version)

Let's turn now to the details of the WordGuess class, whose source code is shown in Figures 8.27 and 8.28. The game needs to have a supply of words from which it can choose a secret word to present to the players. The getSecretWord() method will take care of this task. It calculates a random number and then uses that number, together with a switch statement, to select from among several words that are coded right into the switch statement. The secret word is stored in the secretWord variable. The currentWord variable stores the partially guessed word. Initially, currentWord consists entirely of question marks. As the players make correct guesses, currentWord is updated to show the locations of the guessed letters. Because currentWord will change as the game progresses, it is stored in a StringBuffer rather than in a String. Recall that Strings are immutable in Java, whereas a StringBuffer contains methods to insert letters and remove letters.

Figure 8.27. The WordGuess class, Part I.

public class WordGuess extends TwoPlayerGame implements CLUIPlayableGame { private String secretWord; private StringBuffer currentWord; private StringBuffer previousGuesses; private int unguessedLetters; public WordGuess() { secretWord = getSecretWord(); currentWord = new StringBuffer(secretWord); previousGuesses = new StringBuffer(); for (int k = 0; k < secretWord.length(); k++) currentWord.setCharAt(k,'?'); unguessedLetters = secretWord.length(); } // WordGuess() public String getPreviousGuesses() { return previousGuesses.toString(); } // getPreviousGuesses() public String getCurrentWord() { return currentWord.toString(); } // getCurrentWord() private String getSecretWord() { int num = (int)(Math.random()*10); switch (num) { case 0: return "SOFTWARE"; case 1: return "SOLUTION"; case 2: return "CONSTANT"; case 3: return "COMPILER"; case 4: return "ABSTRACT"; case 5: return "ABNORMAL"; case 6: return "ARGUMENT"; case 7: return "QUESTION"; case 8: return "UTILIZES"; case 9: return "VARIABLE"; |

Figure 8.28. The WordGuess class, Part II.

public boolean gameOver() { // From TwoPlayerGame return (unguessedLetters <= 0); } // gameOver() public String getWinner() { // From TwoPlayerGame if (gameOver()) return "Player " + getPlayer(); else return "The game is not over."; } // getWinner() public String reportGameState() { if (!gameOver()) return "\nCurrent word " + currentWord.toString() + " Previous guesses " + previousGuesses + "\nPlayer " + getPlayer() + " guesses next."; else return "\nThe game is now over! The secret word is " + secretWord + "\n" + getWinner() + " has won!\n"; } // reportGameState() |

The unguessedLetters variable stores the number of letters remaining to be guessed. When unguessedLetters equals 0, the game is over. This condition defines the gameOver() method, which is inherited from TwoPlayerGame. The winner of the game is the player who guessed the last letter in the secret word. This condition defines the getWinner() method, which is also inherited from TwoPlayerGame. The other methods that are inherited from TwoPlayerGame or implemented from the CLUIPlayableGame are also implemented in a straightforward manner.

A move in the WordGuess game consists of trying to guess a letter that occurs in the secret word. The move() method processes the player's guesses. It passes the guessed letter to the guessLetter() method, which checks whether the letter is a new, secret letter. If so, guessLetter() takes care of the various housekeeping tasks. It adds the letter to previousGuesses, which keeps track of all the players' guesses. It decrements the number of unguessedLetters, which will become 0 when all the letters have been guessed. And it updates currentWord to show where all the occurrences of the secret letter are located. Note how guessLetter() uses a for loop to cycle through the letters in the secret word. As it does so, it replaces the question marks in currentWord with the correctly guessed secret letter. The guessLetter() method returns false if the guess is incorrect. In that case, the move() method changes the player's turn. When correct guesses are made, the current player keeps the turn.

The WordGuess game is a good example of a string-processing problem. It makes use of several of the String and StringBuffer methods that we learned in Chapter 7. The implementation of WordGuess as an extension of TwoPlayerGame is quite straightforward. One advantage of the TwoPlayerGame class hierarchy is that it decides many of the important design issues in advance. Developing a new game is largely a matter of implementing methods whose definitions have already been determined in the superclass or in the interfaces. This greatly simplifies the development process.

Reusing code

Let's now discuss the details of the WordGuesser class (Fig. 8.29). Note that the constructor takes a WordGuess parameter. This allows WordGuesser to be passed a reference to the game, which accesses the game's public methods, such as getPreviousGuesses(). The toString() method is identical to the toString() method in the NimPlayerBad example. The makeAMove() method, which is part of the IPlayer interface, is responsible for specifying the algorithm that the player uses to make a move. The strategy in this case is to repeatedly pick a random letter from A to Z until a letter is found that is not contained in previousGuesses. That way, the player will not guess letters that have already been guessed.

Figure 8.29. The WordGuesser class. (This item is displayed on page 395 in the print version)

public class WordGuesser implements IPlayer { private WordGuess game; public WordGuesser (WordGuess game) { this.game = game; } public String makeAMove(String prompt) { String usedLetters = game.getPreviousGuesses(); char letter; do { // Pick one of 26 letters letter = (char)('A' + (int)(Math.random() * 26)); } while (usedLetters.indexOf(letter) != -1); return "" + letter; } public String toString() { // returns 'NimPlayerBad' String className = this.getClass().toString(); return className.substring(5); } } // WordGuesser class |

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 275