76 - Surgical Anatomy of the Trachea and Techniques of Resection and Reconstruction

Editors: Shields, Thomas W.; LoCicero, Joseph; Ponn, Ronald B.; Rusch, Valerie W.

Title: General Thoracic Surgery, 6th Edition

Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

> Table of Contents > Volume I - The Lung, Pleura, Diaphragm, and Chest Wall > Section XIV - Congenital, Structural, and Inflammatory Diseases of the Lung > Chapter 90 - Pleuropulmonary Amebiasis

Chapter 90

Pleuropulmonary Amebiasis

Mohan Verghese

Rajeev Kapoor

Forrest C. Eggleston

Pleuropulmonary amebiasis is almost invariably the result of perforation of an amebic liver abscess through the diaphragm. It accounts for 10% of all deaths from amebiasis. To understand its management, the nature of amebiasis and of the liver abscess it produces must be understood.

AMEBIASIS

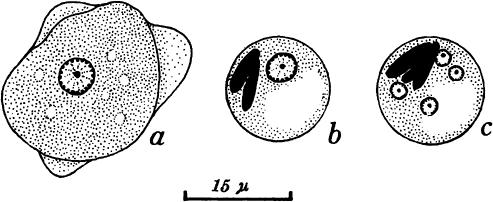

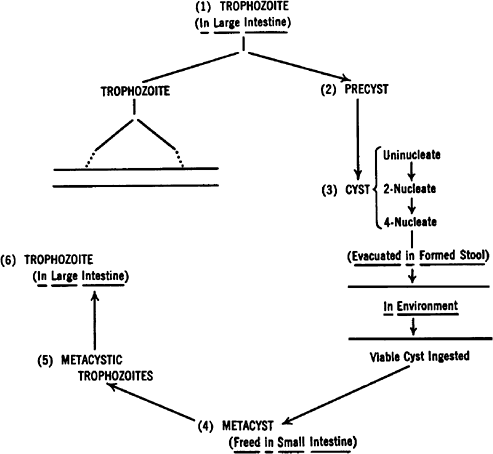

Amebiasis is caused by the protozoan Entamoeba histolytica. The ameba's life cycle has three stages: trophozoite, precyst, and cyst (Fig. 90-1). Infection results from the ingestion of cysts, usually from contaminated food or water. Excystation occurs in the lower ileum. The resulting trophozoites are the active and growing stage of the parasite. Multiplication is by binary fission. The trophozoites can invade the mucosa of the bowel. Invasion is probably the result of physical means combined with production of the lytic substances from which the parasite derives its descriptive name. If the trophozoites do not invade the bowel, they become precysts and then cysts, finally being eliminated in the stool (Fig. 90-2).

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the protozoan Entamoeba histolytica is present in the gastrointestinal tract of more than 10% of the world's population. However, only approximately 10% of those harboring the parasite develop symptomatic infection. Although amebic infestation occurs throughout the world, clinical infection is far more frequent in tropical and subtropical climates, particularly in areas with inadequate sanitation, poor nutrition, poverty, and overcrowding. Stress, decreased resistance, and the administration of corticosteroids can be important contributing factors.

Morphologic differences distinguish all species in the genus Entamoeba except for E. histolytica and E. hartmanni, which are identified primarily by size. E. hartmanni was formerly known as the small race of E. histolytica, and is now considered saprophytic. It is the large race of E. histolytica that produces disease in man. Several strains or species of ameba, morphologically indistinguishable but possibly differing in their pathogenic potential, make up the species complex known as E. histolytica. This may account for differences in clinical findings and therapeutic results in geographically separated centers.

Intestinal amebiasis may be acute or chronic. The acute form produces cramping abdominal pain, diarrhea, and tenesmus. The stool frequently contains blood. The chronic form may persist for a long time with alternating bouts of diarrhea and constipation. Many patients who develop liver abscesses, however, give no history of gastrointestinal symptoms.

AMEBIC LIVER ABSCESS

When amebae invade the colonic mucosa, particularly in the cecum, they may be carried to the liver through the portal venous system. There they lodge in the venules, producing thrombosis that is followed by an infarct, necrosis of liver tissue, and a localized abscess. This is not an abscess in the classic sense, but rather a collection of necrotic liver tissue with white blood cells and amebae in the center. The amebae in the periphery multiply, releasing lytic enzymes, resulting in additional necrosis and enlarging the abscess. No fibrous capsule or clear margin exists between the abscess and the surrounding tissue. Although the parasite does not normally stimulate the intense inflammatory response of other infective agents, it may do so under certain conditions, particularly if secondarily infected.

Because of the combination of the laminar flow of the portal venous system and the high incidence of cecal involvement, the right lobe of the liver is most commonly involved. In his review, Grigsby (1969) found that 85% of amebic liver abscesses were in the right lobe and 15% were in the left lobe; both lobes were involved in 15 to 20% of cases. Our own figures are similar.

Although these abscesses may occur at any age, they are most frequent in the third to fifth decades of life. In adults,

P.1291

men are infected seven to nine times as often as women; in children, no sex difference is noted.

|

Fig. 90-1. Entamoeba histolytica. A. Trophozoite. B. Immature cyst, precystic form. C. Cystic or resistant form. Modified from Faust EC, Russell PE: Clinical Parasitology. 7th Ed. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1964. |

Symptoms of an amebic liver abscess may be present for a few days to many months before the patient seeks help. In the experience of one of us (FCE) and associates (1978), the average duration was 33 days. Symptoms vary, and as a result, the diagnosis is not clear in one third of cases.

Virtually all patients have pain, most commonly in the right hypochondrium (73%). Pain also may occur in the epigastrium, left hypochondrium, or right hemithorax. When associated with diaphragmatic irritation, it may be referred to the shoulder. The pain may be mild, moderate, or severe, and usually is constant. Many patients complain of a swelling in the upper abdomen. Anorexia, fever, and malaise are usual, and patients whose treatment has been delayed may have profound weight loss.

A history of diarrhea, although helpful in making a diagnosis, is given by less than half of all patients. Blood in the stool is noted in only about 25% of patients.

Examination of the abdomen shows a large, tender liver. Softening suggests imminent rupture of the amebic liver abscess. In addition, intercostal pressure reveals tenderness. Pleural effusion is common. Jaundice is uncommon, but when present, it is associated with a poor prognosis.

|

Fig. 90-2. Life cycle of Entamoeba histolytica. Modified from Faust EC, Russell PF: Clinical Parasitology. 7th Ed. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1964. |

Proctosigmoidoscopy is useful only if punctate lesions are found in the mucosa or if amebae are seen on examination of swab material.

Leukocytosis (12,000 to 30,000 cells/mm) is the rule. Liver function tests show moderate elevation of alkaline phosphatase, bilirubin, and transaminases. Serologic tests, if positive, suggest current or previous invasive amebiasis. According to Sharma and colleagues (1988), the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) technique is highly sensitive, is easily available, and can be completed in about 35 minutes. The test may be negative in the first week; the titer may peak in 3 months and decrease to lower but detectable levels in 9 months. This test may not be very useful in endemic areas, where widespread colonic invasion of

P.1292

ameba results in high titers without hepatic involvement. In these areas, its value remains in differentiating it from pyogenic liver abscess and other cystic lesions of the liver. Liu and colleagues (2001) described the usefulness of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in confirmation of the diagnosis of amebiasis by amplification of 16S ribosomal RNA.

|

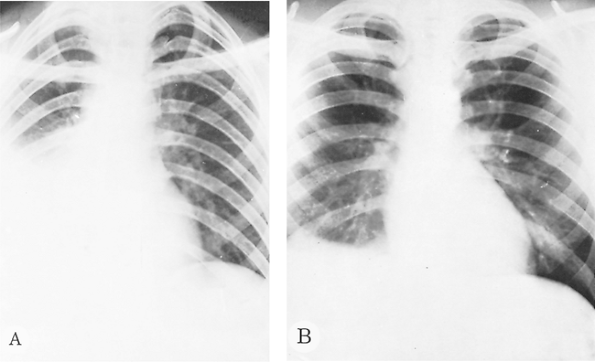

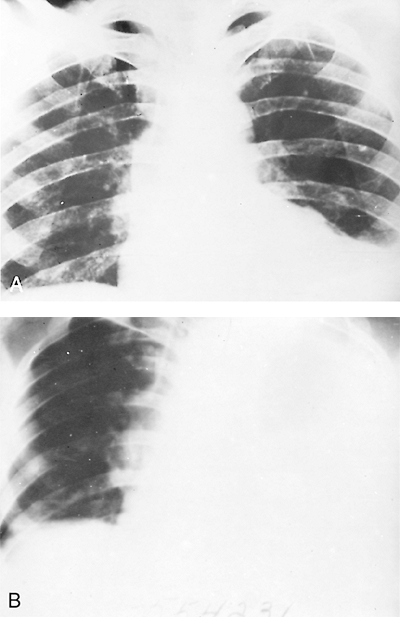

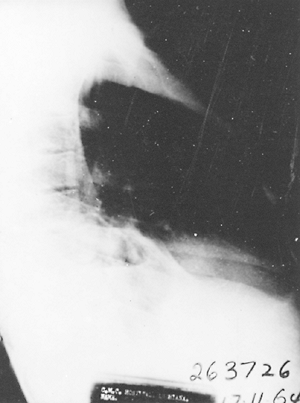

Fig. 90-3. Simple irritative pleuritis with effusion in the right hemithorax. A. Before treatment. B. After treatment. |

|

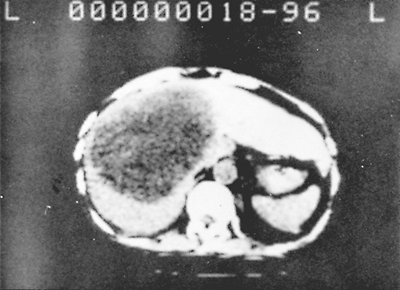

Fig. 90-4. Computed tomographic scan showing a large abscess in the right lobe of the liver. |

Chest radiography usually shows an elevated diaphragm, often accompanied by a pleural effusion (Fig. 90-3). Computed tomography (CT) (Fig. 90-4), ultrasonography (Fig. 90-5), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and isotopic imaging all demonstrate both the presence and site of liver abscesses. However, in the acute situation, CT, MRI, and isotope imaging are not any better than ultrasonography. Ultrasound is inexpensive, is easy to perform, and has a diagnostic accuracy of 90%. Ultrasound is the best investigation for following the size of the abscess on treatment. When aspirated, the pus is usually reddish brown or chocolate brown, the so-called anchovy sauce, although initially, it may be yellowish or even white. Unless the amebic liver abscess was aspirated previously, it is bacteriologically sterile. Amebae can be demonstrated in approximately one half of the abscesses.

|

Fig. 90-5. Sonogram. Parasagittal and subcostal sections show a large liver abscess 6 cm below the skin. |

|

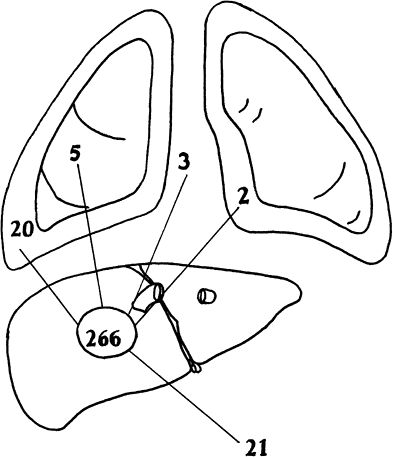

Fig. 90-6. Site of perforation in 266 consecutive patients admitted in our hospital with amebic liver abscess. Thirty (59%) perforations were into the thorax, and 20 were into the abdomen. A total of 51 perforations were seen in 42 patients. |

Because of the lytic nature of the parasite and the lack of encapsulation of amebic liver abscesses, rupture occurs in 10% to 30% of patients. The anatomic location of amebic liver abscesses makes upward or transdiaphragmatic rupture more frequent than downward or infradiaphragmatic rupture (Fig. 90-6).

THORACIC AMEBIASIS

In amebiasis, 70% to 97% of thoracic complications result from extension of an amebic liver abscess through the diaphragm. The type of complication depends on whether the pleural space, lung, or pericardium is involved, either singly or in combination. We shall consider only pleural and pulmonary involvement.

Most patients have the clinical signs of an amebic liver abscess in addition to those related to the thoracic complication.

P.1293

Pleural Involvement

An amebic liver abscess adjacent to the diaphragm may produce irritation and a sympathetic pleural effusion. On chest radiography, the diaphragm is elevated and fixed. The costophrenic angle is obliterated. Sympathetic pleural effusion was present in 15% of cases in our current experience of 266 patients with an amebic liver abscess. Thoracentesis shows that the fluid is clear or serosanguineous and sterile on culture. Amebae are not present. This pleural effusion requires no specific therapy other than that for the causative liver abscess. Should it increase, however, it may presage the rupture of the abscess through the diaphragm and the development of frank empyema. Basal pneumonitis and atelectasis, alone or in combination, are the other complications of an unruptured liver abscess. Ten percent of the patients had basal pneumonitis or atelectasis; 22% of our patients with unruptured amebic liver abscess had pleural effusion, pneumonitis, or both.

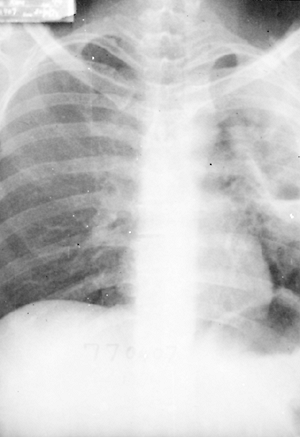

Amebic Empyema

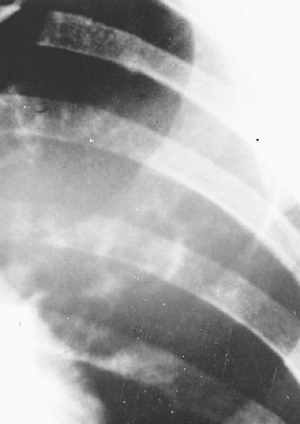

Excluding sympathetic pleural effusion, amebic empyema is the most common of all the pleuropulmonary complications, occurring in 50% to 75% of patients with thoracic amebiasis. In 95% of patients, the empyema is on the right side. Elevation of the diaphragm, friction rub, and effusion usually precede it. The onset can be either insidious or rapid and overwhelming (Fig. 90-7), depending on the size of the perforation and the volume of the abscess. It is accompanied by pain, dyspnea, and, if massive, shock. Some patients complain of a tearing sensation. Radiography of the chest shows opacification of the ipsilateral lung field (Fig. 90-8).

On thoracentesis, purulent, reddish brown or bile-stained fluid is found. During both chest aspiration and establishment of intercostal tube drainage, it is mandatory to go in

P.1294

high on the right lateral intercostal space near the axilla to avoid entry through the already raised diaphragm into the liver. Unless the lung is also involved, the fluid is sterile. Amebae are identified in less than 10% of cases.

|

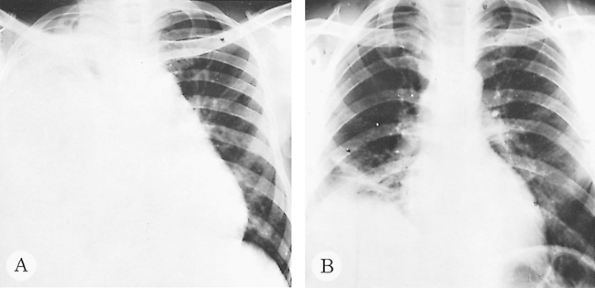

Fig. 90-7. A patient had an acute massive rupture of an amebic liver abscess into the left pleura. A. Radiograph taken before rupture. B. Twelve hours later. This demonstrates the need for urgent treatment. From Eggleston FC: Pitfalls in the surgical management of ALA. Trop Doc 9:178, 1979. With permission. |

|

Fig. 90-8. Pure amebic empyema of the right hemithorax. A. Before treatment. B. After treatment. |

Pleural thickening, often out of proportion to the duration of the empyema, follows rapidly, especially in the presence of secondary infection. Accordingly, treatment must be prompt and vigorous to avoid further complications. In addition to specific drug therapy, the purulent exudate must be removed rapidly. Although repeated aspirations, often combined with the instillation of streptokinase, have been recommended, we agree with Ibarra-P rez (1981) that closed intercostal drainage with the largest cannula possible, combined with strong suction, offers the best chance for prompt and complete reexpansion of the lung. When carried out promptly, secondary surgical procedures other than an occasional rib resection are rarely required. Le Roux and associates (1986) pointed out that subcostal drainage of the amebic liver abscess might be necessary when drainage persists or abscess becomes secondarily infected. Should initial treatment be delayed or inadequate, reexpansion of the lung may be limited and decortication needed.

The mortality rate varies from 14% to 40%, depending on the general condition of the patient and the delay in starting treatment.

Pulmonary Amebiasis

Two types of pulmonary amebiasis occur. The first results from rupture of an amebic liver abscess into the lung, and the second is metastatic (i.e., hematogenous dissemination with no direct communication to the liver). The former is by far the more common.

When pleural symphysis precedes the transdiaphragmatic rupture of amebic liver abscess, the lung is directly involved, particularly the basal segments (Fig. 90-9), the middle lobe, or rarely the lingula. Following a few days of chest pain and nonproductive cough, the patient complains of expectoration of reddish brown or bile-stained material, sometimes in large quantities. Unless flooding of the tracheobronchial tree is overwhelming, the prognosis is good.

Treatment consists of postural drainage, antibiotics to prevent secondary infection, and, most important, specific antiamebic drug therapy. This complication carries the lowest mortality rate of any of the major complications of amebiasis because the liver abscess is usually well walled off from the peritoneal and pleural spaces. In rare cases in which the adhesions are not well formed, rupture of the liver abscess can be into the pleura as well as the bronchi simultaneously. Pleural drainage is required along with the other measures.

Rarely, a persistent bronchobiliary fistula develops. Ragheb and associates (1976) performed lung resection and closure of the fistulous tract.

P.1295

We prefer to drain the liver abscess transabdominally, as one of us (MV) and associates (1979) reported. Lung abscess also can occur but is rare.

|

Fig. 90-9. Involvement of the right lower lobe basal segments by amebic abscess extending from the liver. |

Occasionally, lung involvement is followed by bronchiectasis, usually mild and not severe enough to require resection. Indeed, we have never had to do one.

Metastatic pulmonary amebic lung abscesses are rare and result from hematogenous spread of amebae (Fig. 90-10). Symptoms resemble those of other lung abscesses, with fever, chest pain, cough, and hemoptysis. Occasionally, these parenchymal abscesses rupture into the pleura and produce a localized empyema (Fig. 90-11). Unless amebae can be demonstrated in the sputum or the pleural fluid, the diagnosis of pulmonary amebiasis is difficult and depends on finding evidence of amebiasis elsewhere.

Treatment is similar to that for any other lung abscess, with the addition of specific antiamebic drug therapy.

In approximately 25% of patients, both the pleura and lungs are involved. Treatment includes intercostal drainage with strong suction, reexpansion of the lung, postural drainage, and appropriate antibiotics.

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS

Rarely, an amebic liver abscess ruptures transdiaphragmatically following the institution of specific antiamebic therapy. Undoubtedly, this rupture occurs in an already necrotic area of the diaphragm.

We prefer not to drain the liver abscess routinely, except for acutely sick patients, patients with pleuropulmonary amebiasis, and patients who have failed to respond to treatment. Drainage of a liver abscess is done through the percutaneous route; CT guided aspiration is simpler and safer. Laparotomy is indicated only in patients with multiple liver abscesses or in patients in whom percutaneous drainage and medical management have failed to improve the condition of the patient. Patients with amebiasis, particularly those with pleuropulmonary complications, usually have been sick for a long time and are often economically disadvantaged and malnourished. Consequently, nutritional support is important.

|

Fig. 90-10. Metastatic amebic lung abscess. |

|

Fig. 90-11. Metastatic amebic lung abscess with rupture and localized empyema and bronchopleural fistula. Amebae were seen on smear of empyema fluid. |

|

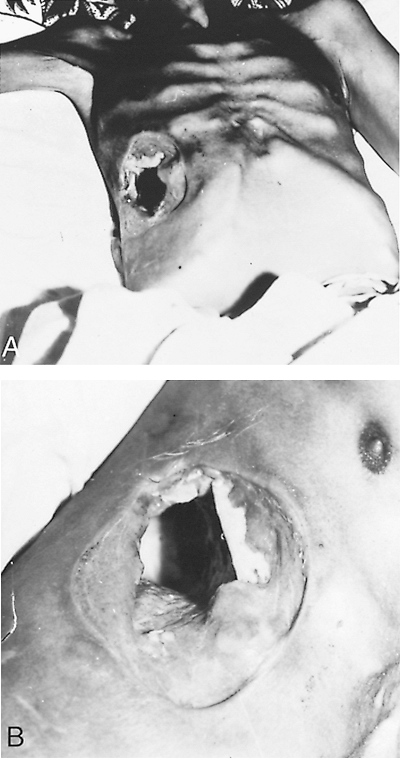

Fig. 90-12. A, B. Necrosis of the chest wall from amebiasis after lung biopsy for suspected malignancy, which resulted in amebic empyema. The patient recovered with antiamebic treatment. |

When diagnosis is delayed, results may be devastating (Fig. 90-12). The increasing use of sonography has permitted earlier diagnosis and treatment of amebic liver abscess. As a result, in our experience, the incidence of pleuropulmonary complications seems to be decreasing (Table 90-1).

P.1296

The incidence, clinical manifestations, and therapeutic response of infections with E. histolytica do not appear to be influenced by a patient's infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) because the rates of symptomatic infection with this organism do not differ between patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and the general population.

Table 90-1. Review of Hospital Admissions for Hepatic Amebiasis from 1980 to Date | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

However, according to Liu and associates (2001), amebic liver abscess and colitis can be a rare presentation of HIV infection in the Far East, although theses authors agree that amebic infection is not regarded as a beacon for concomitant HIV infection. Thus, patients with invasive amebiasis in these geographic areas, especially those with a protracted course or with risk factors of HIV infection, should be tested for HIV. These authors noted three consecutive patients with amebic liver abscess, also later found to be infected with HIV.

ANTIAMEBIC CHEMOTHERAPY

Metronidazole

Most amebic liver abscesses are cured with a regimen of metronidazole, 750 mg orally or intravenously three times per day. Metronidazole produces little toxicity. Oral administration in high doses may be associated with nausea, anorexia, a metallic taste in the mouth, cramps, and diarrhea. These problems are less common with the intravenous route. Although metronidazole is carcinogenic in animals when given in large doses, it has not been proved to be carcinogenic in humans. No evidence that drug resistance develops has yet been demonstrated.

For hepatopulmonary amebiasis, as Jain and co-workers (1990) pointed out, many different acceptable drug regimens are available. Because relapse has been reported after the use of metronidazole alone and because these patients are sicker than patients with uncomplicated amebic liver abscess, we prefer to use a combination of drugs (Table 90-2).

Chloroquine

Chloroquine is generally well tolerated and particularly effective in the amebic liver abscess. It is also effective in pulmonary amebiasis. At the dosage levels used in the treatment of amebiasis, the retinopathy sometimes associated with long-term use of chloroquine does not occur. It should, however, be administered orally, which is not always possible in seriously ill patients.

Dehydroemetine

Dehydroemetine is cardiotoxic, and careful monitoring of the pulse, blood pressure, and electrocardiography is required. Cardiovascular side effects are characterized by hypotension, tachycardia, chest pain, and dyspnea. Electrocardiography shows T-wave inversion and prolongation of

P.1297

the Q-T interval. It can produce severe myositis at the site of injection. The drug is contraindicated in renal and cardiac disease and must be cautiously used in children and elderly patients. We use this drug in patients who are very sick or in patients not responding to a combination of metronidazole and chloroquine. If we see any sign of toxicity, or if the patient has known cardiac problems, we discontinue dehydroemetine or avoid using it.

Table 90-2. Recommended Antiamebic Drug Schedule | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Tinidazole

Tinidazole is as effective as metronidazole and may be better tolerated. The recommended dosage in amebic liver abscess is 800 mg three times daily for 5 days or 2 g daily for 3 days. In children, 50 to 60 mg/kg is given up to a maximum of 2 g. Other nitroimidazole derivatives like nimorazole, secondizole, and ornidazole have produced poorer results than metronidazole and tinidazole.

REFERENCES

Eggleston FC, et al: The results of surgery in amebic liver abscess: experiences in 83 patients. Surgery 83:536, 1978.

Eggleston FC: Pitfalls in the surgical management of ALA. Trop Doc 9:178, 1979.

Faust EC, Russell PE: Clinical Parasitology. 7th Ed. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1964.

Grigsby WP: Surgical treatment of amebiasis. Surg Gynecol Obstet 128: 609, 1969.

Ibarra-P rez C. Thoracic complications of amebic abscess of the liver: report of 501 cases. Chest 79:672, 1981.

Jain NK, et al: Hepatopulmonary amebiasis. Efficacy of various treatment regimens containing dehydroemetine and/or metronidazole. J Assoc Physicians India 38:269, 1990.

Le Roux BT, et al: Suppurative diseases of the lung and pleural space. I. Empyema thoracis and lung abscess. Curr Probl Surg 23:1, 1986.

Liu CJ, et al: Amebic liver abscess and human immunodeficiency virus infection: a report of three cases. J Clin Gastroenterol 33:64, 2001.

Ragheb MI, Ramadan AA, Khalil MAH: Intrathoracic presentation of amebic liver abscess. Ann Thorac Surg 22:483, 1976.

Sharma M, et al: A simple and rapid Dot-ELISA dipstick technique for detection of antibodies to Entamoeba histolytica in amebic liver abscess. Ind J Med Res 88:409, 1988.

Verghese M, et al: Management of thoracic amebiasis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 78:757, 1979.

Reading References

Adams EB, MacLeod IN: Invasive amebiasis. I. Amebic dysentery and its complications. Medicine 56:315, 1977.

Beaver PC, Jung RC, Cupp EW: Clinical Parasitology. 9th Ed. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1984.

Framm SR, Soave R: Agents of diarrhea. Med Clin North Am 81:427, 1997.

Markell EK, Voge M, John DT: Medical Parasitology. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1986.

Rodriguez C. Pulmonary and pleural amebiasis. In Shields TW (ed): General Thoracic Surgery. 2nd Ed. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1983.

Wolfe MS. Amebiasis. In Strickland GT (ed): Hunter's Tropical Medicine. 6th Ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1976.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 203