157 - Neurogenic Structures of the Mediastinum

Editors: Shields, Thomas W.; LoCicero, Joseph; Ponn, Ronald B.; Rusch, Valerie W.

Title: General Thoracic Surgery, 6th Edition

Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

> Table of Contents > Volume II > The Mediastinum > Section XXIX - Primary Mediastinal Tumors and Syndromes Associated with Mediastinal Lesions > Chapter 185 - Benign Germ Cell Tumors of the Mediastinum

Chapter 185

Benign Germ Cell Tumors of the Mediastinum

Mark S. Allen

Victor F. Trastek

Peter C. Pairolero

INCIDENCE AND TERMINOLOGY

The incidence of mediastinal tumors, as noted by Cocks and Kamdar (1994), is approximately 1 in 3,400 hospital admissions. Benign germ cell tumors are uncommon and account for 5% to 10% of all mediastinal tumors. Mullen and Richardson (1986) proposed a useful classification system of mediastinal germ cell tumors. They divided them into three categories: benign germ cell tumors, seminomas, and nonseminomatous germ cell tumors, also called malignant teratomas. The germ cell tumors consist of choriocarcinoma, yolk sac carcinoma, embryonal carcinoma, and teratocarcinoma (see Chapters 186 and 187).

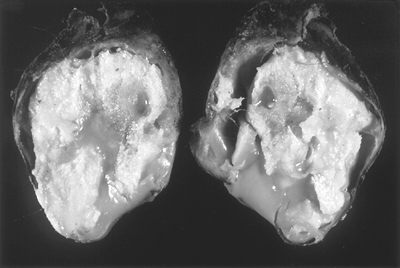

Benign germ cell tumors also have been referred to as epidermoid cysts, dermoids, benign teratomas, or simply teratomas. The term teratoma is derived from the Greek word teras, which means monster, an apt name for these often bizarre-appearing tumors (Fig. 185-1). The terms embryoma, teratoid tumor, and teratoblastoma imply malignancy and are therefore misleading, and should not be used. Similarly, the terms bidermoma and tridermoma, which attempt to describe the number of germ cell layers in the tumor, are cumbersome and awkward and are rarely used. Dermoid cyst is used commonly and is a descriptive term to describe the often cystic nature of this tumor. These tumors are true neoplasms and contain multiple germ cell layers and, therefore, are probably best termed benign teratomas.

Benign teratomas have been defined by Willis (1952) as tumors that are composed of tissue that is foreign to the organ or anatomic site in which they arise. Often included, but not an absolute requirement, is that tissue from all three primordial germ cell layers be present (i.e., ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm). With incomplete differentiation, one or two germ cell layers may be missing.

INCIDENCE AND EPIDEMIOLOGY

Only 5% to 10% of germ cell tumors are extragonadal, but the mediastinum is the most common extragonadal site, as noted in the publication of Hession and Simpson (1996), as well as those of Sohn (1995) and Greif (1997) and their associates. According to Hainsworth and Greco (1989), the exact percentage, however, depends on the age group studied. In a collective review of anterior mediastinal tumors, Mullen and Richardson (1986) found that germ cell tumors accounted for approximately 15% of the anterior mediastinal tumors in adults (85% of these were benign) and 25% in children, all of which were benign.

Typically, germ cell tumors occur in young adults in the second to fourth decades of life with equal sex distribution. Wychulis and colleagues (1971), in a review of 1,064 mediastinal tumors managed surgically between 1929 and 1968 at the Mayo Clinic, found that 99 (9.3%) were teratomas. Most occurred in young adults, with half occurring in individuals 11 to 30 years of age. Benign teratomas had a slight predominance in women as compared with men, however, most series found no sex ratio differentiation. The percentage of benign teratomas was higher in a series from Japan, where Suzuki and co-workers (1983) reported that 23% of mediastinal masses were teratomas. Although not the most common type of mediastinal mass, benign teratomas historically have constituted 80% to 85% of all mediastinal germ cell tumors. However, Davis and associates (1987) reported on 400 mediastinal masses seen at Duke University Medical Center from 1930 to 1986; 42 were germ cell tumors, and of these, only 21 were benign. Whether this reflects an increasing number of malignant germ cell tumors or is only the result of the patterns of referral is unknown.

Almost all benign teratomas occur in the anterior compartment of the mediastinum. Only 3% to 8% are located in either the posterior portion of the visceral compartment or the paravertebral regions, as illustrated by the review by Shirodkar and co-workers (1997). The benign lesions in the anterior compartment may protrude to one side or the other. Shirodkar and associates (1997) found that 46 projected to the left, 34 toward the right, and 6 were midline.

|

Fig. 185-1. Gross photograph of a cross-section of a benign teratoma. Note the hair and sebaceous material present. A well-formed capsule is present that is thin in several areas. |

P.2705

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Theories of origin of benign teratomas must account for their usual location and the presence of multiple germ cell layers. Three theories exist to describe the origin of mediastinal germ cell tumors. One theory, as espoused by Schlumberger (1946), suggests that these tumors arise from cells adjacent to the third and fourth brachial clefts. Because this tissue is juxtaposed to the thymus gland, it is unclear if the tumor arises from thymic tissue or is just intimately adjacent to this organ. Another theory, as noted by Mullen and Richardson (1986), suggests that benign teratomas arise from primordial germinal nests that did not complete the migration from the urogenital ridge to the gonads during development. Lastly, Wychulis and colleagues (1971), as well as Hession and Simpson (1996), believe these tumors may arise from pluripotent cells that have the capacity to form tissue from all three embryonic layers foreign to the area where they are located.

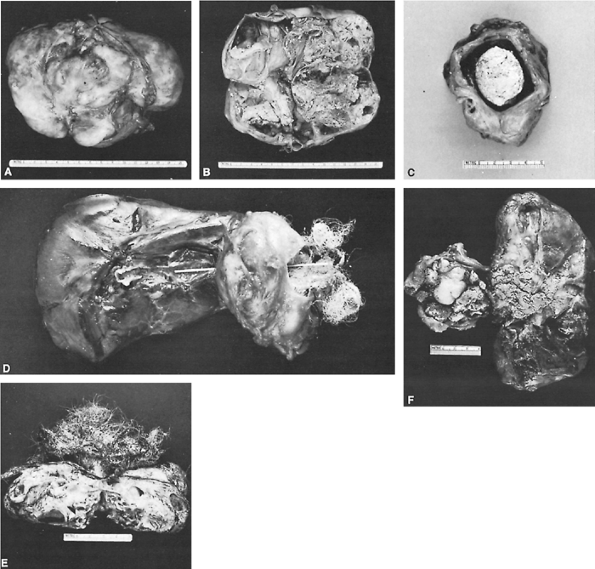

Benign teratomas can be either cystic or solid or a combination of both. Lewis and associates (1983) reported that the average germ cell tumor size was 10.5 8.6 5.4 cm and had an average weight of 415 g (range 48 to 1,820 g). Wall thickness of the encapsulated benign teratoma ranged from 0.5 to 2.0 cm (Fig. 185-2).

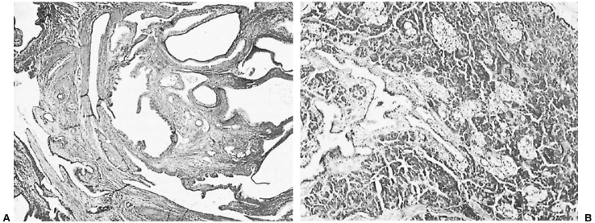

Histologically, Rosado-de-Christenson and associates (1992) rightly pointed out that benign teratomas consist of all three primordial layers: ectoderm (skin and hair), mesoderm (bone, fat, and muscle), and endoderm (respiratory epithelium and gastrointestinal tract) (Fig. 185-3). Therefore, it is not surprising to find all types of histologic tissue in teratomas. Skin, pilosebaceous tissue, smooth muscle, fat, and respiratory epithelium occur in more than half of the tumors. Teeth, bone, cartilage, neural tissue, and pancreatic tissue have been reported in benign teratomas by Willis (1952) and Wychulis and colleagues (1971), as well as by many of the aforementioned researchers. These tumors, when mature, contain well-differentiated tissue components. When immature, they contain less well-differentiated tissue. In infants, immature teratomas behave similarly to mature teratomas, but in older patients, Sohn and co-workers (1995) have pointed out that the immature teratomas are more aggressive, resembling malignant teratomas.

PRESENTATION

Benign teratomas present equally in men and women and can be found as early as the first month of life and as late as the eighth decade of life. The tumor tends to be slow growing, thus, many patients have no signs or symptoms when the mass is initially discovered. Le Roux (1960) reported that 62% of his patients were asymptomatic, although Lewis and associates (1983) found only 36% of their patients were so.

The most common symptom is chest pain, which may be accompanied by dyspnea, cough, and fever, as observed by Robinson and associates (1994).

P.2706

The chest pain is most commonly substernal or in the pectoral area on the side of the mass. Occasionally, when the tumor erodes into an airway, patients may cough up hair (trichophytosis) or sebum, which is pathognomonic of a benign mediastinal teratoma, as pointed out by one of us (MSA) (1995). Hemoptysis also can occur, presumably from irritation of the bronchial mucosa by the tumor or from erosion into a vascular structure.

|

Fig. 185-2. Mediastinal benign teratomas can present with numerous tissue abnormalities: A. A well-circumscribed mediastinal teratoma. B. On cross section, the teratoma is multicystic and contains hair. C. A mediastinal teratoma presented as an encapsulated, central cystic mass containing sebaceous material. Mediastinal benign teratomas can present with numerous tissue abnormalities: D. A mediastinal circumscribed cystic teratoma, containing considerable hair, which has ruptured into a bronchus as indicated by the probe. Evidence of hair can be seen extruding from the bronchus. E. Multiloculated cystic teratoma with abundant hair. F. A cystic teratoma containing hair and sebaceous material that has ruptured into an adjacent bronchus, filling the bronchus with the sebum. |

Presenting symptoms also can occur from pressure on surrounding structures. This is especially true in the newborn

P.2707

patient with a benign teratoma. Billmire and Grosfeld (1986) reported 12 children with benign teratomas; four had wheezing, one had superior vena cava syndrome, and a newborn presented with severe respiratory distress. Breathlessness and a protuberant abdomen have been reported by Shirodkar and colleagues (1997) in a 4-month-old child with a large bilobar teratoma that compressed the airway and displaced abdominal contents. Thambi Dorai and associates (1998) reported that, in neonates, compression of cardiopulmonary organs can cause serious deformities, including pulmonary hypoplasia, tracheomalacia, and cardiac development abnormalities. Other pressure symptoms include Horner's syndrome, spinal cord compression, intercostal neuralgia, and dysphagia, as noted in the review of Cocks and Kamdar (1994).

|

Fig. 185-3. A. Hematoxylin and eosin histologic preparation (original magnification 40) showing mature teratoma with multiple cystic spaces lined by a variety of fully differentiated epithelium, including epidermal, bronchial, and gut epithelium. The smooth muscle and cartilage are present within the stroma. B. Hematoxylin and eosin histologic preparation (original magnification 150) of a mediastinal teratoma containing mature pancreatic tissue with numerous islets of Langerhans. |

Benign teratomas, in addition to erosion into an airway, also can rupture and fistulize into the pleural space or pericardial space, as recorded by Maeyama and co-workers (1999), and cardiac tamponade was described by Marsten and associates (1966). Sasaka and co-workers (1998) reported that up to 36% of the benign teratomas ruptured into the lung or bronchial tree. Obviously, symptoms depend on what structure the tumor ruptures into. If rupture occurs into the lung, an abscess, as noted, or coughing of hair or sebaceous material can result. If the teratoma erodes into the pleural space, an effusion or an empyema can develop with chest or back pain. In two pediatric patients with rupture of a benign teratoma into the pleural cavity, elevation of carcinoembryonic antigen, CA-125, and CA19 9 was reported by Matsubara and associates (2001). These markers returned to normal after surgical resection. The elevated levels of carcinoembryonic antigen were also noted by Hiraiwa and collaborators (1991). These researchers pointed out that this finding does not necessarily mean that the tumor is malignant. Rarely, patients present with rupture into the superior vena cava or aorta. The cause of rupture is postulated to be from the tumor-secreting proteolytic enzymes with subsequent digestion of the tumor wall. Alternatively, as suggested by Hiraiwa and co-workers (1991), rupture may be caused by expansion, leading to ischemia of the wall.

Benign teratomas can secrete chemical substances that lead to a variety of symptoms. They have been reported by Honicky and dePapp (1973) and Pierson (1975), Walden (1977), and Job (1975) and their associates to secrete insulin, human chorionic gonadotropin, follicle-stimulating hormone, and androgenic substances, resulting in sexual precocity. Pancreatic enzyme secretion from a benign teratoma can cause inflammation and necrosis that may subsequently result in secondary bacterial infection. These paraneoplastic syndromes are quite unusual but have been reported by Sommerland (1980) and Ashour (1993) and their colleagues, as well as by Southgate and Slade (1982), among others.

Physical examination is usually unrevealing. Rarely, if the tumor is quite large, bulging of the anterior chest wall can be seen. Occasionally, clubbing of fingers or toes is present. The tumor also can fistulize to the skin and present as a draining sinus.

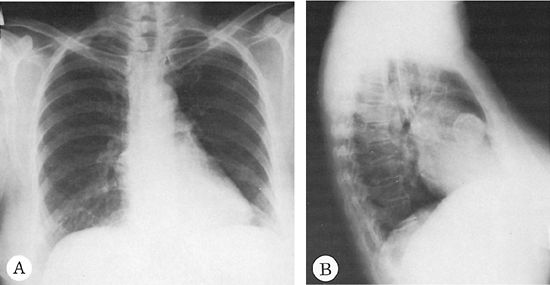

EVALUATION

Most benign teratomas are discovered on routine chest radiography. A well-circumscribed anterior mediastinal mass is suggestive of a benign teratoma (Fig. 185-4). Infrequently, the mass may be located in the posterior region of the mediastinum in the paravertebral area. A rare radiographic presentation of a benign teratoma simulating a loculated subpulmonary effusion was recorded by Robinson and co-workers (1994). Usually benign teratomas have a uniform density on chest radiography. Calcification, according to Le Roux (1962), which may represent bony structures such as teeth or calcification in the cyst wall, may be present in 25% to 33% of patients. Occasionally the edges of the mass are bosselated if the mass is cystic.

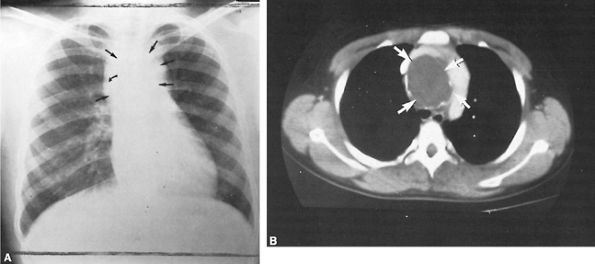

Computed tomographic (CT) scan with contrast enhancement is the diagnostic procedure of choice for evaluation

P.2708

P.2709

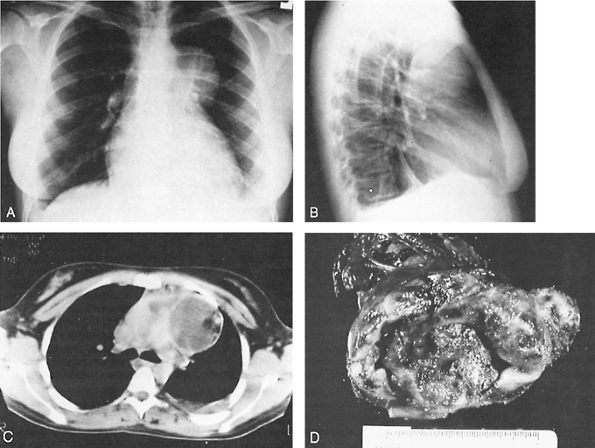

of mediastinal abnormalities found on chest radiography (Fig. 185-5). A CT can define the full extent of the mass and also helps characterize the mass. Usually, a CT demonstrates a thick-walled cystic mass. When areas of calcification are intermixed within areas of fat density, the diagnosis of teratoma can be made with a high degree of certainty as noted by Brown (1987) and Suzuki (1983) and their associates (Fig. 185-6). However, fatty tissue is found in only 50% of benign cystic teratomas. In contrast, Quillin and Siegel (1992) studied 15 patients with benign teratomas, three of which were in the mediastinum. Most appeared cystic on the CT, and the Hounsfield units ranged from 10 to 20 in the fluid areas, suggestive of gelatinous or serous fluid. Overall, 73% of teratomas had areas of fatty tissue, and areas of calcification were observed in 67%. Occasionally, as pointed out by Hession and Simpson (1996), these low-density fatty globules can be seen to rise to the top of the fluid in the cyst during CT scanning, just as a globule of wax rises in a lava lamp. When a solid teratoma is imaged, Sohn and colleagues (1995) emphasize that it is indistinguishable from other anterior mediastinal masses, including thymoma, thyroid tumors, lymphoma, or other germ cell tumors such as a seminoma. Of some interest is that Quillin and Siegel (1992) could not differentiate benign from malignant tumors based on size alone.

|

Fig. 185-4. Posteroanterior (A) and lateral (B) radiographs of the chest revealing a mass with calcified rim in the anterior compartment of the mediastinum. Excision proved the lesions to be a teratomatous dermoid cyst. |

|

Fig. 185-5. A. Posteroanterior chest radiograph showing an anterosuperior mediastinal mass (straight arrows) with calcification in the wall (curved arrow). B. CT scan with contrast showing a low-density cystic mass, calcified wall (arrows), and spreading of the opacified vessels. From Brown LR, et al: Computed tomography of benign mature teratomas of the mediastinum. J Thorac Imaging 2:66, 1987. With permission. |

|

Fig. 185-6. Benign germ cell tumor in an asymptomatic young adult woman. A, B. Posteroanterior and lateral radiographs of chest show lesion projecting into left hemithorax. C. CT scan of chest reveals growth to the right, as well as posterior displacement of tracheal bifurcation and the great vessels. Inhomogeneous nature of mass with admixture of fatty and solid tissues is well demonstrated. D. Gross specimen of resected lesion, which was densely adherent to surrounding tissues. |

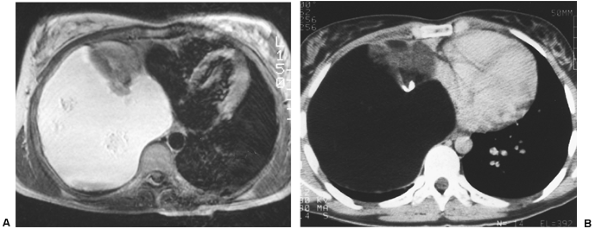

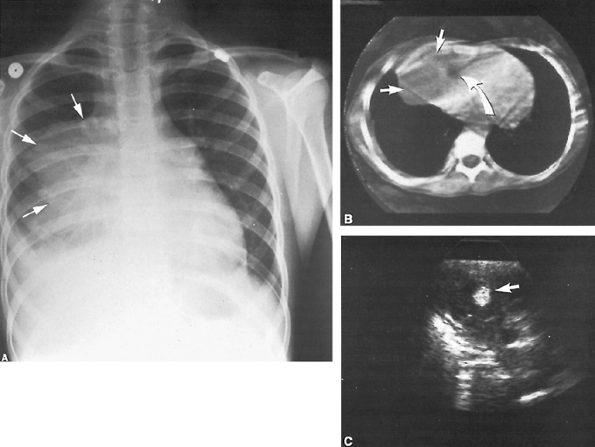

The role of magnetic resonance (MR) imaging in evaluating teratomas is not fully known, but the ability to determine vascular structures without contrast may be a distinct advantage (Fig. 185-7). The ability of MR imaging to clearly demonstrate a fatty component of the mass may help differentiate a mediastinal teratoma from other mediastinal tumors, as described by Ruzal-Shapiro and associates (1989). Ultrasonography also has been used by Ikezoe and associates (1986) as a diagnostic adjunct in determining the mixed components, cystic and solid, of these tumors (Fig. 185-8). Saito and colleagues (1988) used ultrasound-guided biopsy to correctly identify all six patients with a benign teratoma in a group of 45 patients presenting with a mediastinal mass. Kubota and co-workers (1996) used positron emission tomography (PET) to image 22 mediastinal tumors. There was one patient in the series who had a teratoma, and the uptake of fluorodeoxyglucose was low.

INVASIVE STUDIES

Transthoracic needle biopsy of suspected teratomas remains controversial. If the mediastinal mass is believed to be a metastatic neoplasm, then needle biopsy is certainly reasonable. For most other masses, however, needle biopsy allows examination of only a small amount of tissue and may be inadequate for definitive diagnosis.

TUMOR MARKERS

Tumor markers should be obtained in all young adult patients with an anterior mediastinal mass. Most common markers that should be obtained include -fetoprotein and -human chorionic gonadotropin. When either is elevated, a malignant germ cell tumor should be the diagnosis. Additional markers include catecholamines, adrenocorticotropic hormone, 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid, 3,5,3 -triiodothyronine, thyroxine, and carcinoembryonic antigen. Unlike -fetoprotein and -human chorionic gonadotropin, however, these other markers, when elevated, do not imply malignancy but are suggestive of paraneoplastic symptoms. Consequently, these latter tumor markers should not be routinely obtained.

|

Fig. 185-7. A. Magnetic resonance image of a benign teratoma in the right inferior-anterior mediastinum. B. CT of same patient demonstrating calcification in a benign teratoma. |

|

Fig. 185-8. A. Posteroanterior chest radiograph showing an anterior mediastinal mass (arrows) with right pleural effusion and atelectasis of the right lower lobe. B. CT scan showing the lower portion of the same mass with a solid component (straight arrows), as well as a single area of low-density fat (curved arrow). C. Ultrasonography of echogenic area consistent with fat in solid portion of the mass (arrow). From Brown LR, et al: Computed tomography of benign mature teratomas of the mediastinum. J Thorac Imaging 2:66, 1987. With permission. |

P.2710

TREATMENT

The treatment of choice for benign germ cell tumors is total extirpation before complications ensue. Resection may be accomplished via a median sternotomy, lateral thoracotomy, or, rarely, a clamshell incision. These benign teratomas may frequently become adherent to adjacent structures (pericardium 54%; lung 52%; vascular structures 30%; and thymus 23%). As emphasized by Lewis and associates (1983), involvement of these structures can make the resection more difficult, tedious, and extensive. Complete excision, including involved lung, thymus, or pericardium if necessary, usually can be accomplished, but tissue may need to be left behind to avoid injury to vital neural or vascular structures. Sivathasan (1987) recorded that if some of the mass has to be left behind, it rarely enlarges. If the tumor has fistulized to the lung, a pulmonary resection may be necessary. Other treatment options have been described. Catania and co-workers (1997) reported treating a huge posterior teratoma with partial resection, removal of the inner lining of the cyst, and injection of tetracycline into the mass to prevent the reaccumulation of fluid that was symptomatic for the patient.

Operative mortality and morbidity for a benign teratoma in the mediastinum are both low. Although Lewis and colleagues (1983) reported five deaths in 86 patients, all occurred before 1945. Similarly, Davis and associates (1987) reported no operative deaths in 21 patients after resection of a benign mediastinal teratoma.

PROGNOSIS

The prognosis of benign teratoma after excision is excellent, even when complete excision is impossible. Postoperative irradiation or other adjuvant measures are not indicated in any of these patients. The 10-year survival rate for the 86 patients reported by Lewis and colleagues (1983) was 92.8%. Billmire and Grosfeld (1986) reported a 100% survival rate in 12 patients after resection of a benign teratoma of the mediastinum with a follow-up of 5 years.

REFERENCES

Allen MS: Benign mediastinal germ cell tumors. In Wood DE, Thomas CR (eds): Mediastinal Tumors Update, 1995. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 1995, p. 37.

P.2711

Ashour M, et al: Spontaneous intrapleural rupture of mediastinal teratoma. Respir Med 87:69, 1993.

Billmire DF, Grosfeld JL: Teratomas in childhood: analysis of 142 cases. J Pediatr Surg 21:548, 1986.

Brown LR, et al: Computed tomography of benign mature teratomas of the mediastinum. J Thorac Imaging 2:66, 1987.

Catania A, et al: Conservative surgical treatment for a giant thoracoabdominal benign teratoma. Acta Chir Belg 97:130, 1997.

Cocks CE, Kamdar HH: Mediastinal teratoma: two case reports. East Afr Med J 71:63, 1994.

Davis RD Jr, Oldham HN Jr, Sabiston DC Jr: Primary cysts and neoplasms of the mediastinum: recent changes in clinical presentation, methods of diagnosis, management, and results. Ann Thorac Surg 44:229, 1987.

Greif J, et al: Benign cystic teratoma simulating organized empyema. Pediatr Pulmonol 23:310, 1997.

Hainsworth JD, Greco FA: Mediastinal germ cell neoplasms. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1989.

Hession PR, Simpson W: Case report: mobile fatty globules in benign cystic teratoma of the mediastinum. Br J Radiol 69:186, 1996.

Hiraiwa T, et al: Rupture of a benign mediastinal teratoma into the right pleural cavity. Ann Thorac Surg 51:110, 1991.

Honicky RE, dePapp EW: Mediastinal teratoma with endocrine function. Am J Dis Child 126:650, 1973.

Ikezoe J, et al: Ultrasonography of mediastinal teratoma. J Clin Ultrasound 14:513, 1986.

Job JC, et al: Pubert pr coce paraneoplastique chez un enfant. Teratome mediastinal avec s cr tion de gonadotrophine chorionique. Arch Fr Pediatr 32:471, 1975.

Kubota K, et al: PET imaging of primary mediastinal tumours. Br J Cancer 73:882, 1996.

Le Roux BT: Mediastinal teratoma. Thorax 15:333, 1960.

Le Roux BT: Cysts and tumors of the mediastinum. Surg Gynecol Obstet 115:695, 1962.

Lewis BD, et al: Benign teratomas of the mediastinum. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 86:727, 1983.

Maeyama R, et al: Benign mediastinal teratoma complicated by cardiac tamponade: report of a case. Surg Today 29:1206, 1999.

Marsten JL, Cooper AG, Ankeney JL: Acute cardiac tamponade due to perforation of a benign mediastinal teratoma into the pericardial sac. Review of cardiovascular manifestations of mediastinal teratomas. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 51:700, 1966.

Matsubara K, et al: Spontaneous rupture of mediastinal cystic teratoma into the pleural cavity: report of two cases and review of the literature. Pediatr Hematol Oncol 18:221, 2001.

Mullen B, Richardson JD: Primary anterior mediastinal tumors in children and adults. Ann Thorac Surg 42:338, 1986.

Pierson M, et al: Teratome du Mediastin et pubert pr coce [Klinefelter's syndrome. Trilogoy of Fallot. Teratoma of the mediastinum and early puberty]. Pediatrie 30:185, 1975.

Quillin SP, Siegel MJ: CT features of benign and malignant teratomas in children. J Comput Assist Tomogr 16:722, 1992.

Robinson LA, Rikkers LF, Dobson JR: Benign mediastinal teratoma masquerading as a large multiloculated effusion. Ann Thorac Surg 58:545, 1994.

Rosado-de-Christenson ML, Templeton PA, Moran CA: Mediastinal germ cell tumors: radiologic and pathologic correlation. Radiographics 12: 1013, 1992.

Ruzal-Shapiro C, Abramson SJ, Berdon WE: Posterior mediastinal cystic teratoma surrounded by fat in a 13-month-old boy. Value of magnetic resonance imaging. Pediatr Radiol 20:107, 1989.

Saito T, et al: Ultrasonically guided needle biopsy in the diagnosis of mediastinal masses. Am Rev Respir Dis 138:679, 1988.

Sasaka K, et al: Spontaneous rupture: a complication of benign mature teratomas of the mediastinum. AJR 170:323, 1998.

Schlumberger HG: Teratoma of the anterior mediastinum in the group of military age. Arch Pathol 41:398, 1946.

Shirodkar NP, et al: Conjoined gastric and mediastinal benign cystic teratomas. Case report of a rare occurrence and review of literature. Clin Imaging 21:340, 1997.

Sivathasan C: Mediastinal benign teratoma in Singapore. Ann Acad Med Singapore 16:322, 1987.

Sohn L, et al: Radiology/pathology conference at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School. Benign mediastinal teratoma. N J Med 92:241, 1995.

Sommerland BC, Cleland WP, Yong NK: Physiological activity in mediastinal teratomas. Atlas Tumor Pathol [2nd Series Fascicle. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology], 1980.

Southgate J, Slade PR: Teratomatoid cyst of the mediastinum with pancreatic enzyme secretion. Thorax 27:476, 1982.

Suzuki M, et al: Computed tomography of mediastinal teratomas. J Comput Assist Tomogr 7:74, 1983.

Thambi Dorai CR, et al: Mediastinal teratoma in a neonate. Pediatr Surg Int 14:84, 1998.

Walden PAM, et al: Primary mediastinal trophoblastic teratomas. Thorax 32:752, 1977.

Willis RA: The spread of tumors in the human body. London: Butterworth, 1952.

Wychulis AR, et al: Surgical treatment of mediastinal tumors. A 40-year experience. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 62:379, 1971.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 203