XXV - Anatomy

Editors: Shields, Thomas W.; LoCicero, Joseph; Ponn, Ronald B.; Rusch, Valerie W.

Title: General Thoracic Surgery, 6th Edition

Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

> Table of Contents > Volume II > The Mediastinum > Section XXIX - Primary Mediastinal Tumors and Syndromes Associated with Mediastinal Lesions > Chapter 181 - Evaluation of Results of Thymectomy for Nonthymomatous Myasthenia Gravis

function show_scrollbar() {}

Chapter 181

Evaluation of Results of Thymectomy for Nonthymomatous Myasthenia Gravis

Alfred Jaretzki III

To understand the controversies concerning the results of thymectomy for autoimmune nonthymomatous myasthenia gravis (MG), five basic issues need to be addressed. First, and of paramount importance, the reader must have an understanding of evidence-based information in order to evaluate properly clinical research reports. Second, although many clinicians caring for these patients, including the author, are convinced that thymectomy is important in the treatment of MG, it has not been proved. Third, before the report of the Myasthenia Gravis Task Force by the author and colleagues (2000a, 2000b), there had been no uniform criteria to define MG or measure the response to therapy. Fourth, the comparative analyses that have been employed in analyzing the results of thymectomy have been flawed and misleading in most instances. And fifth, although a total thymectomy is considered indicated, there are controversies as to what constitutes complete removal of the thymus, whether it is necessary to remove microscopic foci of thymus, to what extent the various surgical resectional techniques accomplish the desired goal, and whether it make a difference.

In this review based on previous analyses, this author (1997, 2003) attempts to clarify these controversial issues. Evidence also is presented in support of the thesis that the more complete the thymic resection the better the results. And most important, recommendations are submitted that well-designed controlled prospective studies are mandatory if these controversies are to be resolved.

RATIONALE FOR TOTAL THYMECTOMY

Total thymectomy has always been considered the goal of surgery in the treatment of MG. In 1941, Blalock and co-workers reported that complete removal of all thymus tissue offers the best chance of altering the course of the disease. This goal has subsequently been reiterated by most leaders in the field. Clinical observations have supported this thesis. Incomplete resections, both transcervical and transsternal, have been followed by persistent symptoms that were later relieved by the removal of residual thymus at reoperation. In addition, studies by Masaoka and Monden (1981) and Matell and associates (1981), comparing aggressive with limited resections, support the premise that the more thymus removed, or more precisely the less thymus left behind, the higher the remission rate.

Furthermore, Penn and colleagues (1977) demonstrated that complete neonatal thymectomy in rabbits prevented experimental autoimmune MG, whereas incomplete removal did not, and it has now been demonstrated, as indicated by Wekerle and M ller-Hermelink (1986), as well as by Penn (1981) and Younger (1997) and their co-workers, that the thymus plays a central role in the autoimmune pathogenesis of MG.

Accordingly, the belief that a total thymectomy is indicated has been virtually unanimous. Recently, however, in defense of extended transcervical and video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) thymectomy techniques, Mack and associates (1996), Mack and Scruggs (2000), and Mack (2000), as well as Suen and Cooper (2000), have questioned the necessity of removing all the perithymic fat, even though this fat is known frequently to contain microscopic foci as well as lobules of thymus.

SURGICAL ANATOMY OF THE THYMUS

Although reports by Kirby and Ginsberg (1991, 2000) and Yim and Izzat (2000) have recently depicted the thymus as a well-defined bilobed encapsulated gland, this is not the case. Surgical-anatomic studies by this author and Wolff (1988) and Masaoka and associates (1975) on patients with MG have demonstrated that the thymus is widely distributed in the neck and mediastinum, that the

P.2665

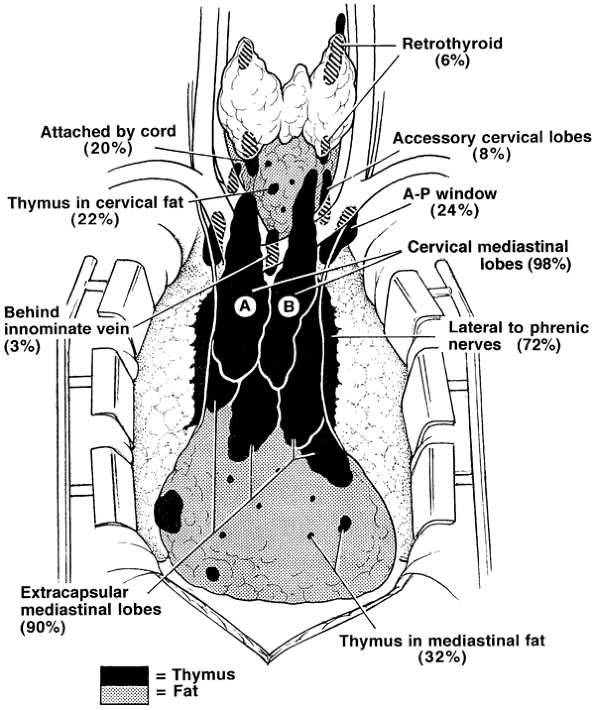

lobar anatomy is variable, that thymus may be unencapsulated and have the appearance of fat, and that small lobules and microscopic foci of thymic tissue may be invisibly distributed in the pretracheal and anterior mediastinal fat from the level of the thyroid to the diaphragm. The presence of thymus in these locations is further confirmed by the findings of thymomas in all these locations. The anatomic distribution of thymus and frequency of location is depicted in Fig. 181-1.

|

Fig. 181-1. Composite anatomy of the thymus based on 50 consecutive surgical anatomic studies after maximal thymectomy for myasthenia gravis. The thymus is indicated in black, and the fat, which may contain islands of thymus and microscopic thymus, is indicated in gray. This illustration represents what is now accepted as the surgical anatomy of the thymus [Jaretzki & Wolff (1988)]. The frequencies (percentages of occurrence) of the variations are noted. There was thymic tissue outside the confines of the cervical-mediastinal lobes (A, B) in the neck in 32% of the specimens and in the mediastinum in 98%. AP, aortopulmonary window. From Jaretzki A III: Thymectomy for myasthenia gravis: analysis of the controversies regarding technique and results. Neurology 48[Suppl 5]:S52, 1997. With permission. |

In the neck, thymus was found outside the confines of the classic cervical-mediastinal lobes (see Fig. 181-1A, B) in 32% of the specimens. Retrothyroid thymus was found as high as the hyoid bone, accessory cervical thymic lobes were medial or lateral to the classic cervical-mediastinal lobes, and gross and microscopic thymus was found in the pretracheal fat. Thymus may also be present in the parathyroid glands or within the thyroid gland.

In the mediastinum, thymus was found outside the confines of the classic cervical-mediastinal lobes in 98% of the specimens. The thymic lobes were also usually adherent to the mediastinal pleura and pericardium, so that attempts to separate the thymus from the pleura and sweep it off the pericardium by blunt dissection resulted in microscopic thymus being left on both surfaces. The thymus extending to and beyond the phrenic nerves consisted of thin, friable, unencapsulated sheets of thymo-fatty tissue, frequently with the gross appearance of fat. The microscopic thymus in the anterior mediastinal fat distal to the thymic lobes extended to the diaphragm, and lobules of thymus were found occasionally in the cardiophrenic fat.

The thymus in the aortopulmonary window region was not encapsulated or localized, usually had the gross appearance of fat, and extended from the level of the pulmonary artery to or above the aortic arch, deep behind the left innominate vein. Superiorly on the right, thymus, when present, was medial or lateral to the superior vena cava and behind the origin of the left innominate vein.

Additionally, in a subsequent autopsy study by Fukai and colleagues (1991), microscopic foci of thymus were found in the subcarinal fat in 7.5% of the specimens.

EXTENT OF THE THYMIC RESECTIONS

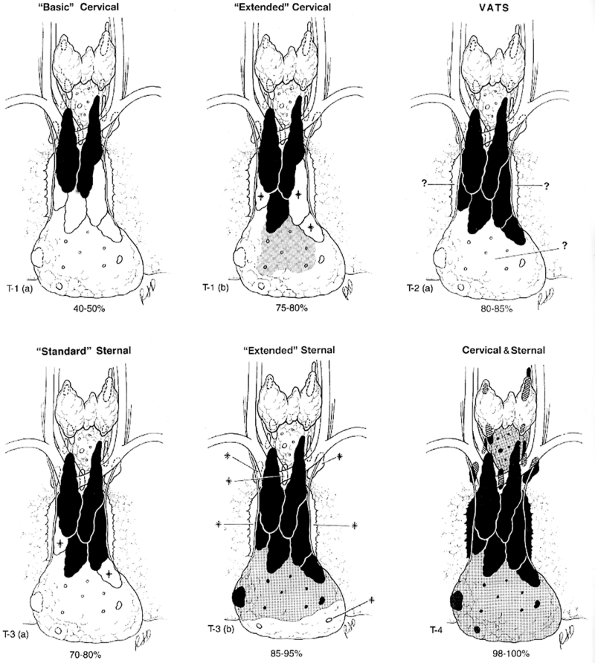

To assist in defining the various thymic resections, the Myasthenia Gravis Task Force, as reported by the author and colleagues (2000a, 2000b), developed a Thymectomy Classification (Table 181-1). Estimates of the amount of thymus removed by each are noted (Fig. 181-2 and Table 181-2). These estimates are based on the author's personal experience with all approaches except videoscopic; the published operative descriptions, illustrations, and photographs of the resected specimens; and review of videos of the VATS resections. These observations indicate that all resections are almost certainly not equal in extent. Details of the resections are recorded in the Appendix (of the Task Force report) and further discussed as follows.

Table 181-1. Myasthenia Gravis Task Force Thymectomy Classification (2000) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||

|

Fig. 181-2. (A F). Estimated extent of six thymectomy resectional techniques. The estimated extent of resection (drawings and percentage range) is based on a review of reports, diagrams, videos when available, specimen photographs, and personal experience. The video-assisted thoracoscopic extended thymectomy (VATET) resection is not illustrated. See Table 181-2. for details. Black, thymus; gray, fat with islands of thymus and microscopic thymus; *, thymic lobes that may or may not be removed; ?, thymo-fatty tissue that may or may not be removed by the designated procedure; white, tissue not removed; VATS, video-assisted thoracic surgery. Modified from Jaretzki A III: Thymectomy for myasthenia gravis: analysis of the controversies regarding technique and results. Neurology 48[Suppl 5]:S52, 1997. With permission. |

P.2666

Basic Transcervical Thymectomy

The basic transcervical thymectomy (T-1a), as described by Kark and Kirschner (1971) and Kark and Papatestas (1971), is limited to the removal of the intracapsular portion of the central lobes (see Fig. 181-1A, B). More recently, modifications by Ferguson (1999) include employing extracapsular dissection, and modifications by Kirby and Ginsberg (2000) include removal of some mediastinal fat separately. Although originally touted as a total thymectomy by Kark and Kirschner (1971), it is unequivocally a limited resection, incomplete in both the neck and mediastinum.

The limited extent of these resections is confirmed by the findings of 2 to 60 g of residual thymus following many reoperations

P.2667

after an initial transcervical resection, as reported by Henze (1984), the author (1988), Kornfeld (1993), Masaoka (1982), Miller (1991), and Rosenberg (1983) and their co-workers, including the finding of a thymoma by Austin and co-workers (1983).

Table 181-2. Estimated Extent of Seven Thymectomy Resectional Techniques and Description of Surgical Maneuvers Used | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Extended Transcervical Thymectomy

The extended transcervical thymectomy (T-1b) was designed by Cooper and associates (1988). Variations include the addition by Durelli and colleagues (1991) of a partial median sternotomy and the associated use of mediastinoscopy by Klingen and co-workers (1977). The proponents of these techniques have claimed that about the same amount of tissue is removed as the aggressive transsternal procedures. However, as reported by Calhoun (1999) and Shrager (2002) and their co-workers, cervical and mediastinal perithymic fat (which may contain thymus) may not be removed, and as warned by Cooper and associates (1988), described in a textbook by Kirby and Ginsberg (1991), and photographed by Hagan and Patterson (1995), this resection appears to be usually less extensive than the original description.

Classic Video-assisted Thoracic Surgery Thymectomy

The classic VATS thymectomy (T-2a) has a number of proponents, including Mineo (1996), Roviaro (1994), Ruckert (1999), Sabbagh (1995), and Yim (1995) and their associates, as well as Sugarbaker (1993) and Mack and Scruggs (2000). No attempt is made to remove the accessory thymus in the neck. Variations include an infrasternal mediastinoscopy by Uchiyama and colleagues (2001). Although photographs of the specimens by Mack and Scruggs (2000) confirm the described extent, others show a more limited resection. In a surgical-anatomical study on eight cadavers by Ruckert and colleagues (2000), incomplete resection was more frequent with the right-sided approach than the left. As warned by Mack and Scruggs (2000), thymectomy is an advanced VATS procedure that should only be undertaken by surgeons well versed in simpler VATS operations and who have the enthusiasm and patience to pursue minimally invasive techniques.

Video-assisted Thoracic Surgery Extended Thymectomy

The video-assisted thoracic surgery extended thymectomy (VATET; T-2b) was described by Novellino (1994) and Scelsi (1996) and their co-workers and includes bilateral thoracoscopic approaches as well as a standard neck dissection. Although conceptually, both in the neck and the mediastinum, this procedure should be more thorough than a unilateral VATS procedure, the undated video the author reviewed does not confirm the reported extent in either the neck or the mediastinum.

P.2668

Standard Transsternal Thymectomy

The standard transsternal thymectomy (T-3a) was used by the pioneers Blalock (1941), Clagett and Eaton (1947), and Keynes (1946). Currently, however, as described by Olanow and Wechsler (1995) and Trastek and Pairolero (1994), the resections are more extensive than the original procedure but less extensive than the extended transsternal operations. Variations include smaller incisions with the addition of videoscopy by Granone and co-workers (1999), a small T incision with partial sternotomy by Miller and associates (1982), and a small transverse skin incision with partial sternotomy by LoCicero (1996) and Pego-Fernandes (2002) and colleagues.

The findings by this author (1988), Miller (1991), and Rosenberg (1986) and their colleagues of residual thymus in the neck and mediastinum at reoperation following standard transsternal resections confirms that this technique may produce an incomplete resection. Accordingly, most MG centers since the early 1980s consider it incomplete and have abandoned it; these include Bulkley (1997), Fischer (1987), Frist (1994), Fujii (1991), Hatton (1989), the author (1988), Kagotani (1985), Masaoka (1996), Monden (1985), Mulder (1989), Nussbaum (1992), Olanow (1987), and Steinglass (2001) and their colleagues.

Extended Transsternal Thymectomy

The extended transsternal thymectomy and its variations have been described and employed by Detterbeck (1996), Fischer (1987), Frist (1994), Fujii (1991), Hatton (1989), Kagotani (1985), Masaoka (2001), Mulder (1996), Nussbaum (1992), Olanow (1982), and Steinglass (2001) and their co-workers. Except for Grandjean and co-workers (2000), a complete median sternotomy is performed. Variations include a video-assisted inframammary cosmetic incision with a median sternotomy by Granone and associates (1999).

Although this author believes that ideally the extent of these procedures should be standardized to remove all the mediastinal tissue that is removed in the combined transcervical-transsternal procedure, including resection of the mediastinal pleural sheets and sharp dissection of the pericardium, as illustrated in the excellent video by Steinglass and colleagues (2001), the extent of the resections vary. Because there is no standard neck dissection, with the cervical extensions of the thymus being removed from below, these techniques may leave small amounts of thymus in the neck. Importantly, however, as expressed by Mulder (2000), many believe that the risk to the recurrent laryngeal nerves in performing the aggressive neck dissection of the combined transcervical-transsternal thymectomy is not justified by the small potential gain. And, of course, prospective studies may prove them correct.

Combined Transcervical Transsternal Thymectomy

The combined transcervical-transsternal thymectomy (T-4), as described by Bulkley (1997), Chen (2003), and the author (1988) and their colleagues, predictably removes en bloc all surgically available thymus in the neck and mediastinum, from above the thyroid to the diaphragm and from phrenic to phrenic and recurrent to recurrent nerves (see Chapter 180). The en bloc technique is used to ensure that islands of thymus in the perithymic fat are not missed and to guard against the potential of seeding of thymus in the wound. As stated by Andersen and co-workers (1986), piecemeal removal of the thymus may herald a poorer prognosis than clean removal. The sharp dissection on the pericardium (with division of the fingers of pericardium that enter the thymus) and the removal of the mediastinal pleural sheets en bloc with the specimen are an integral part of the procedure. Blunt dissection on the pleura and pericardium has been demonstrated to leave microscopic foci of thymus on both surfaces. Skilled surgical technique is required to avoid injury to the recurrent laryngeal, phrenic, and left vagus nerves. Cooper and co-workers (1989) have described the maximal resection as the benchmark against which the other resectional procedures should be measured.

THYMECTOMY LITERATURE

Data Collection Problems

At this time, as previously reviewed by this author (1997, 2003), it is extremely difficult to compare data from one institution with another because of a virtual lack of uniformity in the reporting of results. Perhaps, more importantly, all the studies have been retrospective and, therefore, as emphasized by Sanders and co-workers (2001), do not address the extreme variability and unpredictability of MG, the differing response to treatment among patients with different subtypes of MG, nor the variability inherent in the selection of patients for thymectomy. The problems of analysis have been compounded by a lack of common definitions of disease severity and response to therapy and by a lack of objective preoperative and postoperative assessment criteria as well as differing patient populations, differing accompanying therapy, and differing details of evaluation.

Clinical classifications have been used to stratify patients and evaluate results, yet there have been at least 15, often conflicting, classifications. Furthermore, these classifications are not quantitative, do not accurately describe changes in disease severity, are not a reliable measure of response, and should not be used in the comparative analysis of results. Although remission is the measurement of choice in defining results following thymectomy, as noted by McQuillen and Leone (1977), Oosterhuis (1981), and Viet and Schwab (1960),

P.2669

there has been no uniform definition, and patients are frequently recorded in remission when symptomatic, when receiving medication (including corticosteroids), or both. Although improvement and changes in mean grade are frequently used as a comparative measure of response, they are poorly defined, usually lack quantitation, and are unreliable comparative measures of thymectomy results. In addition, in most studies evaluating combinations of thymectomy and immunosuppression, the patients are not compared with a control group and do not follow a predefined schedule of medications and dose reduction that is required in assessing the additive benefit of thymectomy and immunosuppression. As noted by Sanders and associates (2001), when patients continue to take immunosuppressive medications after thymectomy, it is not possible to infer retrospectively the effects of thymectomy itself.

In comparing results of different techniques, other confounding factors also are frequently ignored. These include (a) failure to assess or define the length of illness preoperatively, (b) failure to record the length of postoperative follow-up, (c) failure to record exacerbations (relapses) after a remission, (d) failure to consider the rate of spontaneous remissions, (e) muddying of the analysis by inclusion of multiple surgical techniques or combining two or more series with differing definitions and standards, (f) inclusion of patients with thymoma, although they may do much less well after thymectomy and thereby skew the results unpredictably, (g) inclusion of reoperations when most patients at the time of the reoperation have had severe symptoms of very long duration and have failed earlier thymectomy for undetermined reasons, (h) use of meta-analysis based on mixed and uncontrolled data, (i) failure to include morbidity and mortality data, and (j) failure to include quality-of-life and cost-benefit analyses.

Data Analysis Problems

As noted by this author (1997) and Weinberg and colleagues (2000), the statistical analyses and comparison of the data are also frequently flawed. Uncorrected crude data, although unacceptable and invalid, is the most commonly used form of analysis comparing the various thymectomy resectional techniques. It is easily recognized and is simply developed by dividing the number of remissions by the number of patients operated upon or divided by the number of patients followed. Even the differing denominators in the two subsets (patients operated upon versus patients followed) are not comparable, yet they have frequently been compared without comment. Among other deficiencies, it does not include any important follow-up information, especially significant in the myasthenic patient. Statements derived from uncorrected crude data, such as all resections produce comparable results, must be ignored, and this type of analysis should be abandoned. Why peer-reviewed journals continue to publish this type of analysis is unclear.

Correcting crude data for mean length of follow-up demonstrates the importance of including follow-up information in the evaluation of the myasthenic patient and confirms the fallacy of comparing uncorrected crude data. Although corrected crude data allow a rough comparison of uncorrected crude remission rates, importantly, they are also not statistically sound and should not be used as a substitute for life table or hazard analysis.

Proper Data Collection and Analysis

The recommendations for clinical research standards prepared by the Myasthenia Gravis Task Force by the author and colleagues (2000a, 2000b) provide standards for clinical research, including outcome guidelines, and are strongly recommended for use in studies on the results of thymectomy.

The preferred statistical technique for the analysis of remissions following thymectomy, as recommended by Lawless (1982) and Weinberg and co-workers (2000), is the Kaplan and Meier (1958) life table analysis. As noted by Durelli and associates (1991) and Olak and Chiu (1993), it uses all follow-up information accumulated to the date of assessment, including information on patients subsequently lost to follow-up and on those who have not yet reached the date of assessment. Unfortunately, this analysis has been rarely used in evaluation of the results following thymectomy.

Hazard rates (remissions per 1,000 patient-months), as described by Blackstone (1996), are considered acceptable. They correct for length of follow-up and censor patients lost to follow-up. However, these rates depend on the risk (remissions per unit of time) being constant, which may not be the case in MG. Hazard rates have also been only rarely employed.

WHAT ARE THE RESULTS FOLLOWING THYMECTOMY?

Thymectomy versus Medical Management

There is a paucity of data, no American Academy of Neurology (AAN) class I prospective randomized studies, as described by Goodin and associates (2002), or even satisfactory prospective class II data, that compare medical management of MG and thymectomy. Accordingly, at this time, there is no unequivocal answer to this question. The available data, however, do suggest a thymectomy benefit.

Most impressive is the classic Mayo computer-assisted retrospective matched study, reported by Buckingham and associates (1976), of patients with nonthymomatous

P.2670

MG, ages 17 to older than 60 years, in which much better results were demonstrated following thymectomy than with medical management. Eighty of 104 surgical patients were matched satisfactorily from the files of 459 medically treated patients. Using crude data corrected for length of follow-up, complete remission was experienced in 35% of the surgical patients (at an average 19.5 years of follow-up) compared with 7.5% of the medical group (at an average 23 years of follow-up), even though only a limited standard transsternal thymectomy (T-3a) was being performed at that time. The mortality rates from MG, 14% surgical and 34% medical, are no longer applicable. In addition, this study has the disadvantages of occurring in the era before effective use of immunosuppression, employing corrected crude analysis, and being retrospective.

An evidence-based review by Gronseth and Barohn (2000), of thymectomy in nonthymomatous MG, included 21 controlled but nonrandomized studies published between 1953 and 1998. Even though the thymectomy techniques were in many instances the limited basic transcervical (T-1a) and the limited standard transsternal operations (T-3a), in other words partial resections, the authors found positive associations in most studies between thymectomy and MG remission. After thymectomy, patients were twice as likely to attain medication-free remission than nonoperated patients. In addition to the disadvantage of being a retrospective meta-analysis, as noted, most resections were incomplete. Thus, if this meta-analysis is otherwise valid, based on the comparison of results in relation to extent of resection (discussed in next section), a total thymectomy can be expected to produce a higher remission rate than demonstrated in this analysis of incomplete thymic resections.

At this time, Newsom-Davis and colleagues (2002) are organizing a prospective randomized multiinstitutional international study. It is designed to establish in generalized autoimmune nonthymomatous myasthenia gravis whether immunosuppressive medication and an aggressive extended transsternal thymectomy (T-3b) confer added benefits to treatment by immunosuppressive medication alone. If the results are significantly better with the addition of a thymectomy, it should confirm in a prospective study that thymectomy is effective in the treatment of MG. Long-term remission analysis of the two arms should also be of great interest.

Although doubts have been expressed about the effectiveness of thymectomy by McQuillen and Leone (1977) and Rowland (1980), and these quotations are still frequently sited, Rowland stated in a 2001 letter to Newsom-Davis in relation to the study in preparation (personal communication): A trial of thymectomy is only about 50 years late.

Comparison of Results Based on Type of Thymectomy

At this point, it is extremely difficult to compare the results of the various thymectomy techniques because, as noted, the studies are retrospective and there is a virtual lack of uniformity in the collection and reporting of data. However, the most reliable available studies, albeit retrospective and uncontrolled, do indicate that the more extensive the resection, the better results.

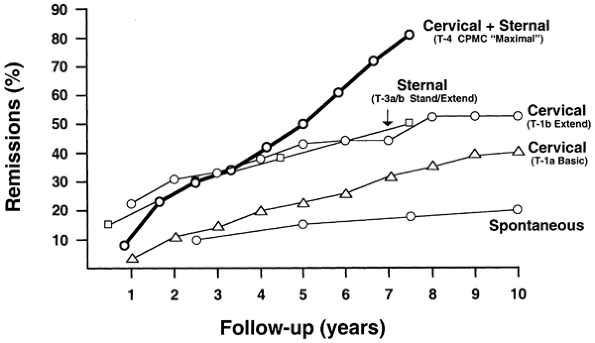

In the author's (1997) review of the published reports of thymectomy from 1970 to 1996, 49 studies were identified as having sufficient data to compare with the combined transcervical-transsternal maximal thymectomy. Only four of the studies included life table analysis, Shrager and co-workers (2002) have recently been reported a fifth, 43 used uncorrected crude data analysis alone, and only 2 of the latter included hazard analysis. Three meta-analyses of this information (life table, hazard, and crude corrected for length of follow-up) support the premise that the more aggressive the resection, the higher the rate of remission.

|

Fig. 181-3. Remission rates (life table analysis) following four thymectomy techniques for nonthymomatous myasthenia gravis. This analysis suggests that the more extensive the resection, the better the results. Importantly, however, the studies are uncontrolled and retrospective, baseline characteristics are not uniform, and statistical confirmation would require the data be available for coanalysis. Life table analyses of extended transsternal thymectomy and videoscopic thymectomy are not available. From Jaretzki A III, et al: Maximal thymectomy for myasthenia gravis. Results. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 95:747, 1988. With permission. Cervical + sternal: (T-4 CPMC maximal ). The combined transcervical & transsternal maximal thymectomy [Jaretzki & Wolff (1988)]. Sternal: (T-3a/b stand/extend). Lindberg's transsternal thymectomy, more extensive than the standard transsternal thymectomy (T-3a), but less extensive than the aggressive extended transsternal thymectomy (T-3b) [Lindberg et at (1992)]. Cervical: (T-1b extend). The Cooper-type extended transcervical thymectomy. All the perithymic fat was not removed; the patient cohort included patients with ocular myasthenia gravis, and by definition, some of the patients may not have been in remission [Shrager et al (2002)] Cervical: (T-1a basic). The original Papatestas basic transcervical thymectomy, which, as has been noted, is a limited resection [Papatestas et al (1987)]. Spontaneous: Spontaneous remissions reported in children [Rodriguez et al (1983)]. From Jaretzki A III: Thymectomy for myasthenia gravis: analysis of the controversies patient management. Neurologist (9:77, 2003). With permission. |

Table 181-3. Remission Rates (Hazard) of Three Transsternal Thymectomy Techniques for Nonthymomatous Myasthenia Gravis | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||

P.2671

Life table analyses of remissions of four resectional techniques are available (Fig. 181-3). The results are seen to favor the most extensive resection. The remission rates, for the four procedures for which data are available at 7.5 years follow-up, are, respectively, 81%, 50%, 48%, and 32%. Interestingly, life table analysis of extended transcervical resection, the only one available, does appear to produce results that are equal to the combined transcervical-transsternal resection at 5 years, although not at 6 and 7 years. However, as noted by this author and co-workers (2003), there is some indication that the transcervical resections of Shrager and co-workers (2002) have a more favorable patient cohort and more favorable criteria of evaluation. Unfortunately, there are no life table analysis data available for the extended transsternal thymectomy (T-3b) and the VATS thymectomy (T-2a). The only available life table analysis of spontaneous remissions, for comparison, as reported by Rodriguez and co-workers (1983), is in children and has been reported as 18% at 7.5 years.

Hazard analyses of three transsternal resections have been compared in Table 181-3. The results also favor the maximal resection over the extended transsternal and the standard transsternal thymectomies of Mulder and associates (1983, 1989), although the cohorts are not entirely comparable.

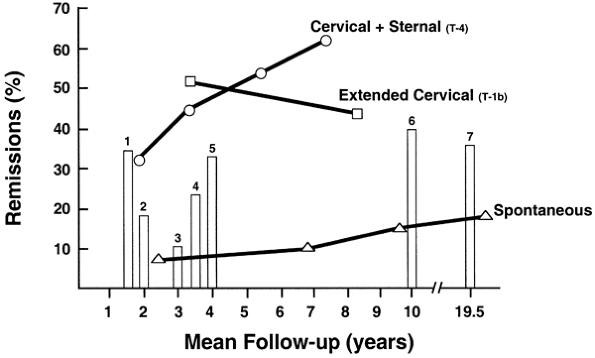

Crude remission rates corrected for length of follow-up (Fig. 181-4) of 13 of the 49 reports reviewed qualified for this meta-analysis and are compared with the maximal thymectomy. The criteria for this author's (1997) selection of the 13 reports were nonthymomatous patients only: remission strictly defined, use of a single surgical technique, and available mean follow-up data. However, other baseline characteristics were not constant. Oosterhuis' (1981) report of corrected crude spontaneous remission rates of 7.5%, 10%, and 18% at 3, 7, and 20 years, respectively, are recorded for comparison.

Although the corrected crude data analysis also supports the relationship between the extent of the thymic resection and remission rates, as previously noted, it is not an acceptable method of comparative analysis and should not replace life table and hazard analyses. More importantly, this analysis confirms the folly of comparing uncorrected crude data. Although this was a common practice by all of us in the past and is still employed by Bril (1998), Budde (2001), Mack (1996), and Masaoka (2001) and their colleagues, as well as by Ferguson (1999), Kirschner (2000), and Yim and Izzat (2000), the practice of comparing uncorrected crude data should be abandoned.

|

Fig. 181-4. Remission rates (crude corrected for mean follow-up) following six thymectomy techniques for nonthymomatous myasthenia gravis. This analysis compares crude data corrected for mean length of follow-up. The corrected crude data, although not recommended to replace life table analysis or hazard analysis, provides a mechanism for a rough comparison of uncorrected crude data, which otherwise cannot be compared. This analysis tends to refute statements, based on uncorrected crude data, that the results of the various thymectomy techniques are comparable. Importantly, however, the studies are uncontrolled and retrospective, and their baseline characteristics are not uniform. The bars represent reported remissions following each type of thymectomy: 1, maximal [Ashour et al (1995)]; 2, video-assisted thoracic surgery; 3, basic transcervical [DeFilippi et al (1994); Mack (1996); Matell et al (1981)]; 4, standard transsternal [Emeryk & Strugalska (1976); Hankins et al (1985); Hayat et al (1995); Matell et al (1981)]; 5, extended transsternal [Clark et al (1980); Hatton et al (1989); Mulder (1996); Nussbaum et al (1992)]; 6, standard transsternal [Wilkins (1981)]; and 7, standard transsternal [Buckingham et al (1976)]. From Jaretzki A III: Thymectomy for myasthenia gravis: analysis of the controversies patient management. Neurologist (9:77, 2003). With permission. Cervical + sternal (T-4). The CPMC combined transcervical and transsternal maximal thymectomy [Jaretzki et al (1997, 1988)]. Extended cervical (T-1b). The extended transcervical thymectomy of Cooper [Bril et al (1998); Cooper et al (1988)] Spontaneous. The spontaneous rate of remission reported [Oosterhuis (1981)]. |

In summary, even though the baseline characteristics of prognostic importance have also not been identified by prospective studies, it seems reasonable to conclude that until well-controlled prospective studies are performed comparing the results of the various thymectomy resectional techniques, these results should serve as the benchmark for remission rates following thymectomy.

P.2672

Pros and Cons of the Less Aggressive Resections

Although less aggressive resections are favored by some, the author notes that the evidence presented in most instances is based on the use of uncorrected crude data which, as previously noted, have no place in the comparative analysis of thymectomy remission rates. This type of analysis has lead Calhoun (1999), Mack (1996), Masaoka (2001), Shrager (2002), and Yim (1999) and their co-workers and others, including Ferguson (1999) and Scott and Detterbeck (1999), to state that results of thymectomy are comparable or equally good regardless of the technique employed. The following are a few specific examples.

Masaoka and coinvestigators (2001) stated that the results of the combined transcervical-transsternal maximal thymectomy (T-4) do not exceed those of the extended transsternal thymectomy (T-3b). Although this may prove to be true with prospective studies and his procedure does have the advantage of avoiding the risk for recurrent laryngeal nerve injury, the comparative analysis cited is based on the use of uncorrected crude data. Ferguson (1999), comparing his transcervical (T-1a) thymectomy with a series of extended transsternal (T-3b) and combined transcervical-transsternal thymectomies (T-4), stated, long-term results compare favorably with those reported after more traditional transsternal operations. The figures cited, however, are uncorrected crude data. Calhoun and co-workers (1999) state that the results of their extended transcervical thymectomy (T-1b) compare favorably to the results following the maximal procedure (T-4), and in the discussion, Cooper states, I take perhaps a little less fat than I used to and since the complete remission rate[s] in all the major series come out exactly the same either the surgical procedures accomplish the same goal [which he believes] or the operation has nothing to do with the outcome. However, their corrected crude remission rate of 44% occurred 8.4 years after surgery, whereas the quoted maximal thymectomy remission rate of 46% occurred only 3.4 years after the operative procedure (see Fig. 181-4).

In defense of the VATS procedure, Mack and co-workers (1996) suggested that the goal of thymectomy should be removal of all gross thymic tissue it has not been demonstrated that microscopic foci are clinically relevant. He defends his position with a figure indicating an approximate 20% remission rate for both the VATS and the combined transcervical-transsternal maximal thymectomy at 23 months. Yim and co-workers (1999) use this same figure. Unfortunately, both have compared their T-2a crude data with the T-4 life table analysis data.

In addition, a report by Papatestas and associates (1987) is frequently quoted as evidence that transcervical resections produce results equivalent to transsternal resections. Although the results in that study were equivalent, the generalization is not valid because the transsternal resections cited were early T-3a very limited standard transsternal resections that removed approximately the same amount of thymus as was removed by the T-1a basic transcervical resections cited.

However, if well-designed prospective studies comparing the minimally invasive procedures with the aggressive transsternal ones demonstrate that (a) the minimally invasive procedures produce results that equal or approximate those of the T-3b and T-4 resections, or (b) the advantages of these or newer techniques, perhaps in combination with targeted immunosuppression, outweigh the more aggressive resections, the author hopes he will be the first to abandon recommending the more aggressive resections.

OUTCOMES RESEARCH

It is now clear that well-designed controlled prospective studies are required to begin to resolve the many conflicting statements and unanswered questions that exist concerning thymectomy in the treatment of MG. Answers to these questions are required if patient protocols and operative techniques are to be properly evaluated. In this era of outcome analyses, these steps are not only desirable but also mandatory.

The ideal method of such evaluation is a prospective randomized clinical trial, class I evidence in the AAN nomenclature as described by Goodin and colleagues (2002). Although a randomized clinical trial directly comparing thymectomy with medical therapy would be difficult to develop and has not been undertaken, as noted at this time, Wolfe and co-workers (2003) are developing a class I study comparing immunosuppression alone with immunosuppression plus the extended transsternal thymectomy (T-3b). However, it would be even more difficult to compare the various thymectomy resectional techniques in a randomized study and therefore unlikely that such randomized trials will be performed in the near future.

Importantly, however, Benson and Hartz (2000) and Concato and co-workers (2000) have demonstrated that properly designed nonrandomized studies, class II or III evidence in the AAN nomenclature, are valid. And, as noted by Kirklin and Blackstone (1993), these studies can produce a large amount of secure knowledge. Accordingly, it is urged that prospective risk-adjusted outcome analyses of nonrandomly assigned thymectomy resectional techniques by two or more institutions be undertaken and supported by granting institutions. Such studies should resolve many of the unresolved issues that will otherwise continue to plague this field. It is also urged that the neurologic and thoracic surgical associations and peer-reviewed journals, in so far as possible, promote the development of such studies.

In addition to a prospective nonrandomized study of this kind, the use of clinical research standards is required. This includes, as recommended by the Myasthenia Gravis Task Force, as reported by this author and colleagues (2000a, 2000b), uniform definitions of clinical classification, quantitative assessment of disease severity, grading

P.2673

systems of postintervention status, comprehensive morbidity and mortality information, and approved methods of analysis. Standardization of numeric grading for all significant variables is required. The assessment process should be independent of the treating teams, as recommended by Gary Franklin, MD, MPH, Co-Chair Quality Standards Subcommittee of the AAN (personal communication). Exacerbations following remission, as well as hospital and long-term morbidity and mortality data, should be compared. A rigid auditing process must be in place to review all the clinical records and to monitor the quality of the database, including validation for completeness and accuracy. The data bank concept, appropriately developed and rigorously monitored, should be particularly useful and practical for multiple institutions to compare the relative value of the various thymectomy techniques.

As previously emphasized, the primary focus of comparative analysis of thymectomy for MG should remain complete stable remission. Survival instruments, which are used in the analysis of remissions, are the most reliable determinants, and the Kaplan-Meier life table analysis is the technique of choice. Levels of clinical improvement can also be evaluated if performed quantitatively, although this is a less definitive measurement. The use of crude data, crude data corrected for length of follow-up, and clinical classifications to compare results has no place in this analysis.

Qualify-of-life evaluation should also be employed because therapy for MG may not be innocuous and may not produce a completely stable remission. Qualify-of-life measures evaluate the impact of intermediate levels of clinical improvement and morbidity of therapy. They should complement, not replace, survival-remission evaluation. Wolfe and co-workers (1999) have developed a functional status instrument for MG assessing activities of daily living. Although disease-specific quality-of-life instruments for MG are highly desirable in this evaluation, as described by Jaeschke and Guyatt (1990), they are not available at this time.

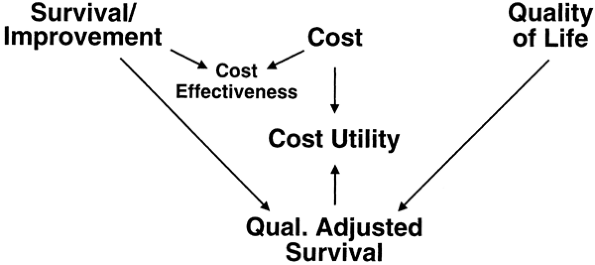

Collaboration with experts in the field of biostatistics and outcomes analysis is mandatory in the design of all studies, in the collection of the data, and in the evaluation of the results. Outcomes analysis guidelines by Weinberg and colleagues (2000), and the accompanying diagram defining their interrelationships (Fig. 181-5), give background information on the available analytical techniques.

CONCLUSION

The only available and appropriately analyzed evidence supports the thesis that thymectomy is effective in the treatment of nonthymomatous autoimmune MG, that the entire thymus should be removed, and that the more complete the thymectomy, the better the results. Importantly, however, even the best available evidence is based on uncontrolled retrospective studies that make comparisons very difficult and perhaps even invalid. Properly designed prospective studies are required to resolve the many unresolved issues. In fact, in view of the necessity to make clinical decisions based on valid data, prospective studies at this time are not only desirable but mandatory.

|

Fig. 181-5. Interrelationship between outcomes instruments. The interrelationship between survival instruments, quality-of-life instruments, and quality adjusted survival cost-effective instruments is demonstrated. Remissions are a Survival function. From Weinberg, A. Myasthenia gravis: outcome analysis. Neurology 55(l):16 30, 2000. With permission. See also online at www.neurology.org. Reprints available from the Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America, Inc., 5841 Cedar Lake Road (Suite 204), Minneapolis, MN, 55416. |

If nothing more, it is hoped that this presentation will lead to a better understanding of the thymectomy controversies, the universal use of uniform clinical research standards, accepted data analysis, and most importantly well-designed prospective studies.

REFERENCES

Andersen M, et al: Transcervical thymectomy in patients with nonthymomatous myasthenia gravis. Scand J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 20:233, 1986.

Ashour MH, et al: Maximal thymectomy for myasthenia gravis. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 9:461, 1995.

Austin EH, Olanow CW, Wechsler AS: Thymoma following transcervical thymectomy for myasthenia gravis. Ann Thorac Surg 35:548, 1983.

Benson K, Hartz AJ: A comparison of observational studies and randomized, controlled studies. N Engl J Med 342:1878, 2002.

Blackstone EH: Outcome analysis using hazard function methodology. Ann Thorac Surg 61:S2, 1996.

Blalock A, et al: The treatment of myasthenia gravis by removal of the thymus gland. JAMA 117:1529, 1941.

Bril V, et al: Long-term clinical outcome after transcervical thymectomy for myasthenia gravis. Ann Thorac Surg 65:1520, 1998.

Buckingham JM, et al: The value of thymectomy in myasthenia gravis: a computer-assisted matched study. Ann Surg 184:453, 1976.

Budde JM, et al: Predictors of outcome in thymectomy for myasthenia gravis. Ann Thorac Surg 72:197, 2001.

Bulkley GB, et al: Extended cervicomediastinal thymectomy in the integrated management of myasthenia gravis. Ann Surg 226:324, 1997.

Calhoun RF, et al: Results of transcervical thymectomy for myasthenia gravis in 100 consecutive patients. Ann Surg 230:555, 1999.

Chen H, et al: Technique of thymectomy. Anterior-superior cervicomediastinal exenteration for myasthenia gravis and thymoma. J Am Coll Surg 195:895, 2003.

Clagett OT, Eaton LM: Surgical treatment of myasthenia gravis. J Thorac Surg 16:62, 1947.

P.2674

Clark RE, et al: Thymectomy for myasthenia gravis in the young adult. Long-term results. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 80:696, 1980.

Concato J, et al: Randomized, controlled trials, observational studies, and hierarchy of research designs. N Engl J Med 342:1887, 2000.

Cooper JD, et al: An improved technique to facilitate transcervical thymectomy for myasthenia gravis. Ann Thorac Surg 45:242, 1988.

Cooper J, et al: Symposium: thymectomy for myasthenia gravis. Contemp Surg 34:65, 1989.

DeFilippi VJ, Richman DP, Ferguson MK: Transcervical thymectomy for myasthenia gravis. Ann Thorac Surg 57:194, 1994.

Detterbeck FC, et al: One hundred consecutive thymectomies for myasthenia gravis. Ann Thorac Surg 62:242, 1996.

Durelli L, et al: Actuarial analysis of the occurrence of remissions following thymectomy for myasthenia gravis in 400 patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 54:406, 1991.

Emeryk B, Strugalska MH: Evaluation of results of thymectomy in myasthenia gravis. J Neurol 211:155, 1976.

Ferguson MK: Transcervical thymectomy. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 11:59, 1999.

Fischer JE, et al: Aggressive surgical approach for drug-free remission from myasthenia gravis. Ann Surg 205:496, 1987.

Frist WH, et al: Thymectomy for the myasthenia gravis patient: factors influencing outcome. Ann Thorac Surg 57:334, 1994.

Fujii N, et al: Analysis of prognostic factors in thymectomized patients with myasthenia gravis: correlation between thymic lymphoid cell subsets and postoperative clinical course. J Neurol Sci 105:143, 1991.

Fukai I, et al: Distribution of thymic tissue in the mediastinal adipose tissue. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 101:1099, 1991.

Goodin DS, et al: Disease modifying therapies in multiple sclerosis: report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the MS Council for Clinical Practice Guidelines. Neurology 58:169, 2002.

Grandjean JG, Lucchi M, Mariani MA: Reversed-T upper mini-sternotomy for extended thymectomy in myasthenia gravis. Ann Thorac Surg 70:1423, 2000.

Granone P, et al: Thymectomy (transsternal) in myasthenia gravis via video-assisted infra-mammary cosmetic incision. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 15:861, 1999.

Gronseth S, Barohn RJ: Practice parameters: thymectomy for autoimmune myasthenia gravis (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 55:7, 2000.

Hagan JA, Patterson GA: Surgery of myasthenia gravis. In Pearson FG (ed): Thoracic Surgery. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1995, p. 1511.

Hankins JR, et al: Thymectomy for myasthenia gravis: 14 year experience. Ann Surg 201:618, 1985.

Hatton P, et al: Transsternal radical thymectomy for myasthenia gravis: a 15-year review. Ann Thorac Surg 47:838, 1989.

Hayat G, Mohyuddin YA, Naunheim K: Efficacy of thymectomy in myasthenia gravis. Moi Med 92:252, 1995.

Henze A, et al: Failing transcervical thymectomy in myasthenia gravis, an evaluation of transsternal re-exploration. Scand J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 18:235, 1984.

Jaeschke R, Guyatt GH: How to develop and validate a new quality of life instrument. In Spilker B (ed): Quality of Life Assessments in Clinical Trials. New York: Raven Press, 1990, p. 47.

Jaretzki A III: Thymectomy for myasthenia gravis: an analysis of the controversies regarding technique and results. Neurology 48(Suppl 5):S52, 1997.

Jaretzki A III: Thymectomy. In Kaminski HJ (ed): Myasthenia Gravis and Related Disorders. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press, 2002, p. 235.

Jaretzki A III: Thymectomy for Myasthenia Gravis: Analysis of controversies patient management. Neurology 9:77, 2003.

Jaretzki A III, Wolff M: Maximal thymectomy for myasthenia gravis. Surgical anatomy and operative technique. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 96:711, 1988.

Jaretzki A III, et al: Maximal thymectomy for myasthenia gravis. Results. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 95:747, 1988.

Jaretzki A III, et al: Myasthenia gravis: recommendations for clinical research standards. Task Force of the Medical Scientific Advisory Board of the Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America. Neurology 55:16, 2000a.

Jaretzki A III, et al: Myasthenia gravis: recommendations for clinical research standards. Task Force of the Medical Scientific Advisory Board of the Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America. Ann Thorac Surg 70:327, 2000b.

Jaretzki A III, et al: Thymectomy for myasthenia gravis: evaluation requires controlled prospective studies [Editorial]. Ann Thorac Surg 76:1, 2003.

Kagotani K, et al: Anti-acetylcholine receptor antibody titer with extended thymectomy in myasthenia gravis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 90:7, 1985.

Kaplan EL, Meier P: Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc 53:457, 1958.

Kark AE, Kirschner PA: Total thymectomy by the transcervical approach. Br J Surg 56:321, 1971.

Kark AE, Papatestas AE: Some anatomic features of the transcervical approach for thymectomy. Mt Sinai J Med 38:580, 1971.

Keynes G: The surgery of the thymus gland. Br J Surg 32:201, 1946.

Kirby TJ, Ginsberg RJ: Transcervical thymectomy. In Shields TW (ed): Mediastinal Surgery. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1991, p. 369.

Kirby TJ, Ginsberg RJ: Transcervical thymectomy. In Shields TW, LoCicero J, Ponn RB (eds): General Thoracic Surgery. 5th Ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2000, p. 2239.

Kirklin JW, Blackstone EH: Clinical studies with non-randomly assigned treatment. In Kirklin JW, Barrett-Boyes BG (eds): Cardiac Surgery. 2nd Ed. New York: Churchill-Livingstone, 1993, p. 269.

Kirschner PA: Myasthenia gravis. In Shields TW, LoCicero J, Ponn RB (eds): General Thoracic Surgery. 5th Ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2000, p. 2207.

Klingen G, et al: Transcervical thymectomy with the aid of mediastinoscopy for myasthenia gravis: eight years' experience. Ann Thorac Surg 23:342, 1977.

Kornfeld P, et al: How reliable are imaging procedures in detecting residual thymus after previous thymectomy? Ann N Y Acad Sci 681:575, 1993.

Lawless JF: Life tables, graphs, and related procedures. In Statistical Models and Methods for Life Table Data. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1982, p. 52.

Lindberg C, et al: Remission rate after thymectomy in myasthenia gravis when the bias of immunosuppressive therapy is eliminated. Acta Neurol Scand 86:323, 1992.

LoCicero J III: The combined cervical and partial sternotomy approach for thymectomy. Chest Surg Clin North Am 6:85, 1996.

Mack MJ: Commentary on minimal access thymectomy for myasthenia gravis. In Yim AP, et al (eds): Minimal Access Cardiothoracic Surgery. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2000, p. 218.

Mack MJ, Scruggs GR: Video-assisted thymectomy. In Shields TW, LoCicero J, Ponn RB (eds): General Thoracic Surgery. 5th Ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2000, p. 2243.

Mack MJ, et al: Results of video-assisted thymectomy in patients with myasthenia gravis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 112:1352, 1996.

Masaoka A, Monden Y: Comparison of the results of transsternal simple, transcervical simple and extended thymectomy. Ann N Y Acad Sci 377:755, 1981.

Masaoka A, Nagaoka Y, Kotake Y: Distribution of thymic tissue at the anterior mediastinum. Current procedures in thymectomy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 70:747, 1975.

Masaoka A, et al: Reoperation after transcervical thymectomy for myasthenia gravis. Neurology 32:83, 1982.

Masaoka A, et al: Extended thymectomy for myasthenia gravis: a 20 year review. Ann Thorac Surg 62:853, 1996.

Masaoka A, et al: Extended trans-sternal thymectomy for myasthenia gravis. Chest Surg Clin N Am 11:369, 2001.

Matell G, et al: Follow-up comparison of suprasternal vs transsternal method for thymectomy in myasthenia gravis. Ann N Y Acad Sci 377:844, 1981.

McQuillen MP, Leone MG: A treatment carol: thymectomy revisited. Neurology 77:1103, 1977.

Miller JI, Mansour KA, Hatcher CR Jr: Median sternotomy T incision for thymectomy in myasthenia gravis. Ann Thorac Surg 34:473, 1982.

Miller RG, et al: Repeat thymectomy in chronic refractory myasthenia gravis. Neurology 41:923, 1991.

Mineo TC, et al: Adjuvant pneumomediastinum in thoracoscopic thymectomy for myasthenia gravis. Ann Thorac Surg 62:1210, 1996.

P.2675

Monden Y, et al: Myasthenia gravis in elderly patients. Ann Thorac Surg 39:433, 1985.

Mulder DG: Extended transsternal thymectomy. Chest Surg Clin North Am 6:95, 1996.

Mulder DG: Extended transsternal thymectomy. In Shields TW, LoCicero J, Ponn RB (eds): General Thoracic Surgery. 5th Ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2000, p. 2233.

Mulder DG, et al: Thymectomy for myasthenia gravis. Am J Surg 146:61, 1983.

Mulder DG, Graves M, Hermann C: Thymectomy for myasthenia gravis: recent observations and comparison with past experience. Ann Thorac Surg 48:551, 1989.

Novellino L, et al: Extended thymectomy, without sternotomy, performed by cervicotomy and thoracoscopic technique in the treatment of myasthenia gravis. Int Surg 79:378, 1994.

Nussbaum MS, et al: Management of myasthenia gravis by extended thymectomy with anterior mediastinal dissection. Surgery 112:681, 1992.

Olak J, Chiu RCJ: A surgeon's guide to biostatistical inferences. Part II. ACS Bull 78:27, 1993.

Olanow CW, Wechsler AS: The surgical management in myasthenia gravis. In Sabiston DC Jr, Spencer FC (eds): Surgery of the Chest. 6th Ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1995.

Olanow CW, Wechsler AS, Roses AD: A prospective study of thymectomy and serum acetylcholine receptor antibodies in myasthenia gravis. Ann Surg 196:113, 1982.

Olanow CW, et al: Thymectomy as primary therapy in myasthenia gravis. Ann N Y Acad Sci 505:595, 1987.

Oosterhuis HJ: Observations of the natural history of myasthenia gravis and the effect of thymectomy. Ann N Y Acad Sci 377:678, 1981.

Papatestas AE, et al: Effects of thymectomy in myasthenia gravis. Ann Surg 206:79, 1987.

Pego-Fernandes PM, et al: Thymectomy by partial sternotomy for the treatment of myasthenia gravis. Ann Thorac Surg 74:204, 2002.

Penn AS, et al: Experimental myasthenia gravis in neonatally thymectomized rabbits. Neurology 27:365, 1977.

Penn AS, et al: Thymic abnormalities: antigen or antibody? Response to thymectomy in myasthenia gravis. Ann N Y Acad Sci 377:786, 1981.

Rodriguez M, et al: Myasthenia gravis in children: long-term follow-up. Ann Neurol 13:504, 1983.

Rosenberg M, et al: Recurrence of thymic hyperplasia after thymectomy in myasthenia gravis: its importance as a cause of failure of surgical treatment. Am J Med 74:78, 1983.

Rosenberg M, et al: Recurrence of thymic hyperplasia after trans-sternal thymectomy in myasthenia gravis. Chest 89:888, 1986.

Roviaro G, et al: Videothoracoscopic excision of mediastinal masses: indications and technique. Ann Thorac Surg 58:1679, 1994.

Rowland LP: Controversies about the treatment of myasthenia gravis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 443:644, 1980.

Ruckert JC, Gellert K, Muller JM: Operative technique for thoracoscopic thymectomy. Surg Endosc 13:943, 1999.

Ruckert JC, et al: Radicality of thoracoscopic thymectomy an anatomical study. Eur J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 18:735, 2000.

Sabbagh MN, Garza JS, Patten B: Thoracoscopic thymectomy in patients with myasthenia gravis. Muscle Nerve 18:1475, 1995.

Sanders DB, et al: Thymectomy for myasthenia gravis in older patients [Letter to editor]. J Am Coll Surg 193:340, 2001.

Scelsi R, et al: Detection and morphology of thymic remnants after video-assisted thoracoscopic thymectomy (VATET) in patients with myasthenia gravis. Int Surg 81:14, 1996.

Scott W, Detterbeck F: Transsternal thymectomy for myasthenia gravis. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 11:54, 1999.

Shrager JB, et al: Transcervical thymectomy for myasthenia gravis achieves results comparable to thymectomy by sternotomy. Ann Thorac Surg 74:320, 2002.

Steinglass KM: Extended transsternal thymectomy for myasthenia gravis [Video]. Minneapolis: Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America, 2001.

Suen HC, Cooper JD: Transcervical approach to the thymus. In: Yim AP, et al (eds): Minimal Access Cardiothoracic Surgery. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2000, p. 199.

Sugarbaker DJ: Thoracoscopy in the management of anterior mediastinal masses. Ann Thorac Surg 56:653, 1993.

Trastek VF, Pairolero PC: Surgery of the thymus gland. In Shields TW (ed): General Thoracic Surgery. 4th Ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1994, p. 1770.

Uchiyama A, et al: Infrasternal mediastinoscopic thymectomy in myasthenia gravis: surgical results in 23 patients. Ann Thorac Surg 72:1902, 2001.

Viet HR, Schwab RS: Thymectomy for myasthenia gravis. In: Veit HR (ed): Records of Experience of Massachusetts General Hospital. Springfield: Charles C. Thomas, 1960, p. 597.

Weinberg A, et al: Myasthenia gravis: outcomes analysis. Neurology 55(1):16–30, 2000. Available at http://www.myasthenia.org/research/Clinical_Research_Standards.htm. Reprints available at Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America, Inc., 5841 Cedar Lake Rd Ste 204, Minneapolis, MN 55416.

Wekerle H, M ller-Hermelink HK: The thymus in myasthenia gravis. Curr Top Pathol 75:179, 1986.

Wilkins EW Jr: Thymectomy. Mod Tech Surg 38:1, 1981.

Wolfe GI, et al: Myasthenia gravis activities of daily living profile. Neurology 52:1487, 1999.

Wolfe et al: Development of a thymectomy trial in nonthymamatous myasthenia gravis patients receiving immunosuppressive therapy. Ann N Y Acad Sci 998:473, 2003.

Yim AP, Izzat MB: VATS approach to the thymus. In Yim AP, et al (eds): Minimal Access Cardiothoracic Surgery. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2000.

Yim AP, Kay RL, Ho JK: Video-assisted thoracoscopic thymectomy for myasthenia gravis. Chest 108:1440, 1995.

Yim AP, et al: Video-assisted thoracoscopic thymectomy for myasthenia gravis. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 11:65, 1999.

Younger DS, et al: Myasthenia gravis: historical perspective and overview. Neurol 48[Suppl 5]:S1, 1997.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 203