154 - The Mediastinum, Its Compartments, and the Mediastinal Lymph Nodes

Editors: Shields, Thomas W.; LoCicero, Joseph; Ponn, Ronald B.; Rusch, Valerie W.

Title: General Thoracic Surgery, 6th Edition

Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

> Table of Contents > Volume II > The Mediastinum > Section XXIX - Primary Mediastinal Tumors and Syndromes Associated with Mediastinal Lesions > Chapter 182 - Benign Lymph Node Disease Involving the Mediastinum

Chapter 182

Benign Lymph Node Disease Involving the Mediastinum

Jemi Olak

Mediastinal lymphadenopathy is most commonly seen within the middle (visceral) compartment of the mediastinum. It occurs most often in the right lower paratracheal, subcarinal, and aortopulmonary window regions. It is seen less often in the anterior and posterior mediastinal compartments. While mediastinal lymphadenopathy is caused most often by malignancy, many benign diseases can cause enlargement of mediastinal lymph nodes, and these will be the focus of this chapter. Benign causes of mediastinal lymphadenopathy are listed in Table 182-1.

MEDIASTINAL GRANULOMATOUS DISEASE

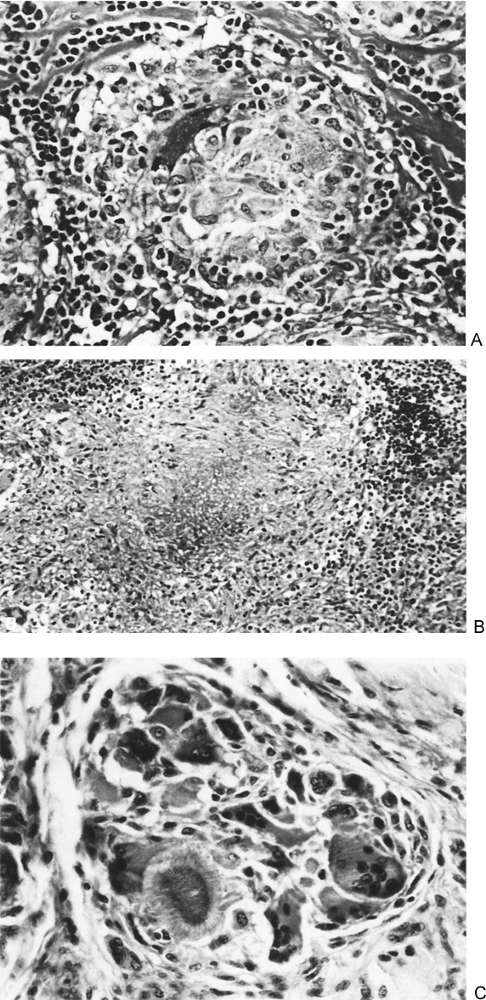

Mediastinal granulomatous disease is the most common benign cause of mediastinal lymphadenopathy. According to Dines and associates (1979), approximately 40% of patients with mediastinal granuloma are asymptomatic. According to Ioachim (1983) they are the result of a specialized immune reaction to insoluble or particulate substances. Generally, granulomas are classified into three types: (a) nonnecrotizing, (b) necrotizing, or (c) foreign body, as illustrated in Fig. 182-1.

Transtracheal and transbronchial fine-needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy are two techniques that have been used to evaluate enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes. In 1994, Wiersema and associates (1994) described the use of esophageal ultrasound-directed FNA of mediastinal lymph nodes to assist in the determination of the etiology of mediastinal lymphadenopathy. This technique is being used to stage esophageal cancer. Cervical mediastinoscopy, video-assisted thoracic surgical (VATS), exploration and biopsy; and, at present infrequently, an anterior mediastinotomy, however, remain the procedures of choice when material is required for pathologic examination. These procedures can be accomplished in an outpatient setting in most cases.

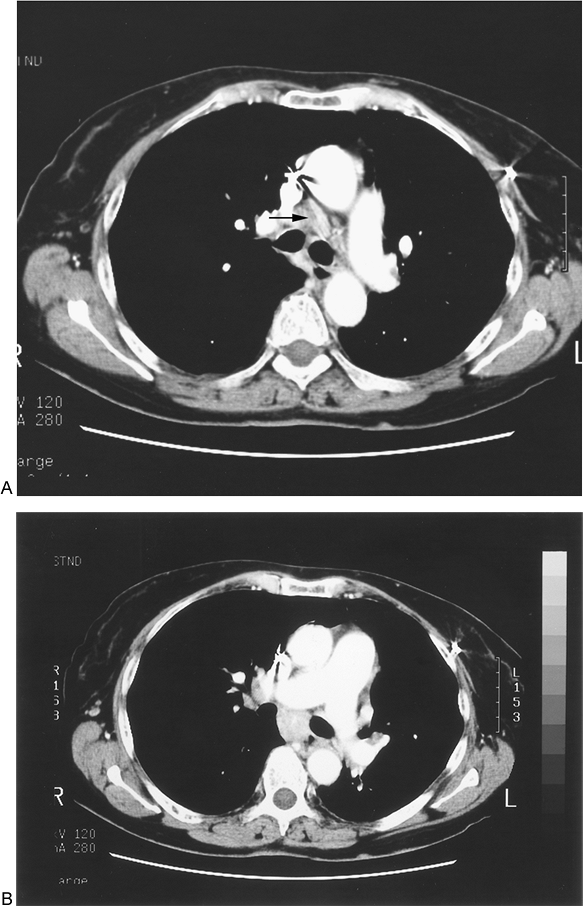

Radiographically, granulomas are solid lesions (Fig. 182-2). Slightly less than half contain calcium. In addition, areas of necrosis may be evident within the granuloma.

When a lymph node that is suspected of harboring granulomatous disease is examined via biopsy, stains for microorganisms should be performed and a biopsy specimen should be sent for mycobacterial and fungal culture. In addition, consideration should be given to an examination of the biopsy material with polarized light, especially if a history of silica exposure has been obtained.

Tuberculosis

Mediastinal lymphadenopathy is a relatively uncommon finding in immunocompetent adults with primary infection due to Mycobacterium tuberculosis when compared to children with primary infection. It is seen more often, however, in immunocompromised adult hosts. The overall decline in the incidence of tuberculosis in the United States was reversed in the mid-1980s as a result of the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) epidemic. Selwyn and associates (1989) reported that AIDS patients have a 7% annual risk for tuberculosis reactivation compared with a 3% to 6% lifetime risk in non-AIDS patients. Pitchenik and Rubinson (1985) reported that 59% of their AIDS patients who developed M. tuberculosis infection had mediastinal or hilar lymphadenopathy. This finding was corroborated by Haramati and associates (1997), who reported that among 98 patients with cultures positive for M. tuberculosis, 60% of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive patients had mediastinal lymphadenopathy on chest radiography compared with 23% of the HIV-negative patients.

Tuberculous granulomas share many features with granulomas secondary to fungal disease. They may be distinguished from other granulomas by staining positive for

P.2677

acid-fast bacilli. In addition, tuberculous granulomas typically feature caseating (coagulative) necrosis. In acute tuberculous lesions, suppuration is a common finding, whereas later on Langhans-type giant cells and caseating necrosis may be predominant features. In older lesions, fibrosis or calcification may be present.

Table 182-1. Benign Mediastinal Lymphadenopathies | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Tuberculous mediastinal lymphadenopathy is generally asymptomatic in its early phases. However, Rafay (2000) recently described a patient who developed vocal cord paralysis as the result of involvement of the left recurrent laryngeal nerve by the enlarged aortopulmonary and subaortic lymph nodes. Complete resolution of the vocal cord paralysis occurred following antituberculous medication. Rafay was only able to find seven other similar cases in the literature; only three were reported in the English-language literature.

Fungal Infection

The most common cause of mediastinal granuloma in adults at present is fungal infection. In order of decreasing frequency, the organisms responsible are Histoplasma capsulatum, Coccidioides immitis, Cryptococcus neoformans, and Blastomyces dermatitidis.

Histoplasma capsulatum is an organism endemic to the eastern and central river valleys of the United States. Edwards and associates (1969) have estimated that more than 80% of the population of these regions are sensitized to the fungus and that approximately 22% of the United States population have been infected with it. Most patients are asymptomatic, although cough and fever may be present. The occurrence of involvement of the left recurrent nerve with hoarseness as the initial complaint was reported by Gilbert and associates (1990). Medical therapy with amphotericin or ketoconazole is reserved for patients with acute infection. According to Dines and associates (1979), fibrosing

P.2678

mediastinitis is a well-documented sequela of exposure to H. capsulatum. It developed in 11 of 31 (34%) of patients with mediastinal granuloma seen at the Mayo Clinic within 2 years of documented exposure. Mole and associates (1995) have reported its occurrence following infection with aspergillus, mucormycosis, cryptococcus, blastomyces, and mycobacteria. Noninfectious causes such as autoimmune disease and sarcoidosis have also been known to result in fibrosing mediastinitis. Fibrosing mediastinitis is believed to result from a delayed hypersensitivity reaction that causes intense inflammation rather than an active fungal proliferation. Mathisen and Grillo (1992) recommend that consideration be given to surgical intervention for patients with large mediastinal granulomas, whether or not they are symptomatic, to avoid the complications associated with the development of fibrosing mediastinitis.

|

Fig. 182-1. Types of granulomatous reactions. A. Nonnecrotizing (epithelioid) granuloma of sarcoid. In the center of the granuloma are epithelioid cells that contain abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm. Epithelioid cells are modified macrophages. Around the granulomas are small dark lymphocytes and bands of collagen. B. A necrotizing granuloma of tuberculosis. In the center of the granuloma is an area of necrosis surrounded by epithelioid cells. Some giant cells are present near the left border. C. A foreign body granuloma of gout. This granuloma shows many foreign body type giant cells with a few epithelioid cells. A crystal of uric acid is present (lower left) in the granuloma. |

|

Fig. 182-2. Computed tomographic (CT) scans demonstrating mediastinal lymphadenopathy secondary to granulomatous disease. A. Precarinal mediastinal lymphadenopathy. The lymph node measures 2.5 cm in short-axis diameter. B. Subcarinal mediastinal lymphadenopathy. The lymph node measures 2 cm in short-axis diameter. |

Fibrosing mediastinitis is the most common benign cause of superior vena cava obstruction. It may also result in airway stenosis, esophageal stenosis, or in the development of esophagorespiratory fistulae. When infection with H. capsulatum reaches this stage, it can have life-threatening implications for which no medical therapy is effective and surgical therapy is palliative. Because carinal pneumonectomy is associated with a high mortality rate (10% to 15%), esophageal and respiratory stents might be considered to palliate selected patients with stenosis, even though their use for this indication remains investigational. Superior vena caval obstruction has been treated by Doty (1982) with spiral vein bypass with acceptable results. Mathisen and Grillo (1992) have recommended treatment of esophagorespiratory fistulae by separation of the esophagus from the tracheobronchial tree and closure of each defect in two layers buttressed by a well-vascularized (e.g., intercostal or serratus anterior) muscle flap. In selected cases, this condition may also be treated with a covered esophageal stent. A subacute form of disease has been described by Urschel and associates (1990). It occurred in six patients known to have had a history of H. capsulatum infection. The subacute form was diagnosed based on rising Histoplasma complement fixation titers and was successfully controlled with oral ketoconazole.

According to Stevens (1995), Coccidioides immitis is endemic to the soils of the southwestern United States (California, Arizona, Texas). Inhalation of the airborne arthrospore is believed to cause approximately 100,000 infections annually in the United States. Sixty percent of acutely infected people are either asymptomatic or manifest upper respiratory tract symptoms. Others present with lower respiratory tract symptoms and radiographic evidence of pulmonary infiltrates, pleural effusion, or hilar adenopathy. While treatment with antifungal agents is indicated for severe primary infection or for those patients in high-risk groups (HIV-positive patients, pregnant women, transplant patients, patients with disseminated disease), most patients recover without therapy. Infection is confirmed by a positive coccidioidal skin test. A lymph node biopsy may be required to rule out other causes of adenopathy and a portion of the specimen should be sent for culture.

While pulmonary infection with Blastomyces follows the inhalation of fungal conidia, Blastomyces dermatitidis, as its name implies, also affects the skin, causing papules that may ulcerate. It is a less common cause of mediastinal lymphadenopathy than H. capsulatum, and is a rare cause of mediastinal fibrosis according to Lagerstrom and associates (1992).

Sarcoidosis

Sarcoidosis is a granulomatous disease of unknown etiology. Organic and inorganic agents as well as genetic predisposition

P.2679

may play a role in its development. The presentation commonly includes mediastinal or hilar lymphadenopathy. It may also be associated with pulmonary infiltrates or nodules. Other manifestations of sarcoidosis are listed in Table 182-2.

Table 182-2. Manifestations of Sarcoidosis | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The disease affects women twice as often as men and African-Americans 10 times more often than whites. It usually manifests in the third though fifth decades of life. When lymphadenopathy is the only manifestation of disease, it is usually of an asymptomatic nature.

Nonnecrotizing granulomas are the pathologic reaction pattern of this disease. According to Fearon and Locksley (1996), once exposed to antigen, an overexhuberant cell-mediated immune response occurs within the target organ as well as a more nonspecific inflammatory response. Newman and associates (1997) report that the diagnosis is established most often with skin or transbronchial lung biopsies and that mediastinal lymph node biopsy is less often required than in the past. Leonard and associates (1997) found that transbronchial lung biopsy established the diagnosis in 70% of cases while the remaining 30% of cases had a positive Wang transbronchial lymph node aspiration. Other causes of granulomatous disease must be excluded before concluding that a patient has sarcoidosis because there are no approved specific definitive diagnostic tests for this disease.

Pulmonary sarcoid has been categorized into three stages. A Consensus Conference report (1994) indicated that stage I disease is characterized by hilar adenopathy without pulmonary infiltrates and remits in 60% to 80% of cases, whereas stage II disease is represented by hilar adenopathy with infiltrates and remits in 50% to 60% of cases. Stage III disease is represented by pulmonary infiltrates without adenopathy and remits in less than 30% of cases. Patients with Lofgren's syndrome have the best prognosis. A poor prognosis has been associated with African-American race, age over 40 years at onset, symptom duration greater than 6 months, absence of erythema nodosum, splenomegaly, involvement of more than three organ systems, or stage III disease. There is no single serologic test available to predict or monitor a patient's clinical course. According to Sharma (1993) and Selroos (1994), corticosteroid treatment is indicated for symptomatic or progressive stage II pulmonary disease and for stage III pulmonary disease.

Silicosis

The overexposure to crystalline silica particles in the mining, construction, manufacturing, and building maintenance industries may result in the development of the fibrotic lung disease silicosis. The development of bilateral hilar adenopathy sometimes associated with eggshell calcification is a common finding in such patients and according to Baldwin and associates (1996) may precede the development of interstitial fibrosis.

Wegener's Granulomatosis

The triad of necrotizing angiitis of the upper and lower respiratory tract and focal glomerulonephritis characterize classical Wegener's granulomatosis (WG) according to Godman and Churg (1954). Carrington and Liebow described a limited form of the disease characterized by vasculitis without glomerulonephritis in 1966. According to Specks and associates (1989), the serum antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody level is 89% specific and 84% sensitive for the diagnosis of Wegener's granulomatosis. When the diagnosis is in doubt, a mediastinoscopic biopsy of enlarged lymph nodes may reveal necrotizing granulomas associated with vasculitis and scattered giant cells, prompting the commencement of corticosteroid therapy. George and associates (1997) reported the presence of mediastinal lymphadenopathy in only 2% (6 of 302) patients with WG and caution that other causes of lymphadenopathy (infection, malignancy) be excluded in patients with WG.

P.2680

CASTLEMAN'S DISEASE

Castleman's disease is an uncommon entity first described by Castleman in 1954. It is most commonly characterized by mediastinal lymph node enlargement and has been variously referred to as lymph nodal hamartoma, angiofollicular lymph node hyperplasia, benign giant lymphoma, giant lymph node hyperplasia, and follicular lymphoreticuloma according to Castleman and associates (1956). The disease is usually asymptomatic. There is no gender or race predominance, and most patients are diagnosed with the disease before age 30. The disease may be associated with many clinical conditions, as outlined in Table 182-3.

The etiology of this disease is unknown at present; however, an immune alteration has been implicated. The overproduction of the cytokine interleukin 6 by the hyperplastic lymph nodes is believed to have a central role in the development of both the localized and multicentric forms of this disease, according to Shahidi and associates (1995).

Localized and multicentric forms are quite distinctive in their clinical features, as outlined in Table 182-4. While the mediastinum is the most common region for the localized form to manifest, all lymph node regions and occasionally nonnodal tissues may be involved. Histologically, hyaline-vascular and plasma cell variants exist, with the former accounting for approximately 90% of cases. Radiologically, the localized form presents as a well-circumscribed, frequently lobulated mediastinal mass.

Samuels and associates (1997) recommended that the localized form be treated with surgical resection and that an excellent prognosis can be anticipated. Adjuvant radiation therapy might be appropriate following incomplete resection or in cases where the disease is not amenable to resection.

Table 182-3. Clinical Conditions Associated with Castleman's Disease | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Table 182-4. Comparison Between Clinical Features of Localized and Multicentric Castleman's Disease | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

P.2681

The multicentric form is commonly treated with single- or multiagent chemotherapy [CVP- (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone) or CHOP-like (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) regimens], corticosteroids, or radiation therapy, but the response is variable and the prognosis is guarded. Close follow-up is recommended in order to detect concurrent or subsequent malignant lesions.

INFREQUENT BENIGN CAUSES OF LYMPHADENOPATHY

Many other diseases are known to be associated with mediastinal lymphadenopathy (see Table 182-1), most often as part of a constellation of findings. In these instances, a careful search for other causes of mediastinal adenopathy may be warranted. Hiller and associates (1995) reported a case of primary amyloidosis that presented as an isolated mediastinal mass without pulmonary involvement. Urschel and Urschel (2000) reported two cases of mediastinal adenopathy due to systemic amyloidosis. Both patients had associated bloody pleural effusions, one unilateral and the other bilateral. Myocardial involvement was also present in one patient, and death occurred within 5 months of diagnosis. The other patient did not respond to prednisone and melphalan and subsequently was managed by a bone marrow transplantation. Yoshioka (1994) reported a case of systemic sclerosis in which mediastinal lymphadenopathy preceded skin and lung involvement. More recently, Ngom and associates (2001) reported mediastinal lymphadenopathy in three patients with congestive heart failure that responded to treatment of the heart failure. The numerous causes of mediastinal lymphadenopathy can be diagnosed with careful consideration of the patients history, physical examination, and both radiologic and laboratory findings.

REFERENCES

Baldwin DR, et al: Silicosis presenting as bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy. Thorax 51:1165, 1996

Carrington CS, Liebow AA: Limited forms of angiitis and granulomatosis of Wegener's type. Am J Med 41:497, 1966.

Castleman B, Iverson L, Menendez VP: Localized mediastinal lymph-node hyperplasia resembling thymoma. Cancer 9:822,1956.

Consensus Conference: Activity of sarcoidosis. Third WASOG meeting, Los Angeles, USA, September 8 11, 1993. Eur Respir J 7:624, 1994.

Dines DR, et al: Mediastinal granuloma and fibrosing mediastinitis. Chest 75:320, 1979.

Doty DB: Bypass of superior vena cava: six years' experience with spiral vein graft for obstruction of superior vena cava due to benign and malignant disease. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 83:326, 1982.

Edwards LB, et al: An atlas of sensitivity to tuberculin, PPD-B, and histoplasmin in the United States. Am Rev Respir Dis 99(suppl):1,1969.

Fearon DT, Locksley RM: The instructive role of innate immunity in the acquired immune response. Science 272:50, 1996.

George TM, et al: Mediastinal mass and hilar adenopathy: rare thoracic manifestations of Wegener's granulomatosis. Arthritis Rheum 40:1992, 1997.

Gilbert EH, et al: Left recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis: an unusual presentation of histoplasmosis. Ann Thorac Surg 50:987, 1990.

Godman GC, Churg J: Wegener's granulomatosis: pathology and review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med 58:533,1954.

Haramati LB, Jenny-Avital ER, Alterman DD: Effect of HIV status on chest radiographic and CT findings in patients with tuberculosis. Clin Radiol 52:31, 1997.

Hiller N, et al: Primary amyloidosis presenting as an isolated mediastinal mass: diagnosis by fine needle biopsy. Thorax 50:908, 1995.

Ioachim HL: Granulomatous lesions of lymph nodes. In Ioachim HL (ed): Pathology of Granulomas. New York: Raven, 1983.

Lagerstrom CF, et al: Chronic fibrosing mediastinitis and superior vena caval obstruction from blastomycosis. Ann Thorac Surg 54:764, 1992.

Leonard C, et al: Utility of Wang transbronchial needle biopsy in sarcoidosis. Ir J Med Sci 166:41, 1997.

Machevsky MA, Kaneko M. Surgical Pathology of the Mediastinum. New York: Raven, 1984, p. 174.

Mathisen DJ, Grillo HC: Clinical manifestation of mediastinal fibrosis and histoplasmosis. Ann Thorac Surg 54:1053, 1992.

Mole TM, Glover J, Sheppard MN: Sclerosing mediastinitis: a report on 18 cases. Thorax 50:280, 1995.

Newman LS, Rose CS, Maier LA: Sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med 336:1224, 1997.

Ngom A, et al: Benign mediastinal lymphadenopathy in congestive heart failure. Chest 119:653, 2001.

Pitchenik AE, Rubinson HA: The radiographic appearance of tuberculosis in patients with the acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). Am Rev Respir Dis 131:393, 1985.

Rafay MA: Tuberculous lymphadenopathy of the superior mediastinum causing vocal cord paralysis. Ann Thorac Surg 70:2142, 2000.

Samuels LE, et al: Castleman's disease: surgical implications. Surg Rounds 20:449, 1997.

Selroos O: Treatment of sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis 11:80, 1994.

Selwyn PA, et al: A prospective study of the risk of tuberculosis among intravenous drug users with human immunodeficiency virus infection. N Engl J Med 320:545, 1989.

Shahidi H, Myers JL, Kvale PA: Castleman's disease. Mayo Clin Proc 70:969, 1995.

Sharma OP: Pulmonary sarcoidosis and corticosteroids. Am Rev Respir Dis 147:1598, 1993.

Specks U, et al: Anticytoplasmic autoantibodies in the diagnosis and follow-up of Wegener's granulomatosis. Mayo Clin Proc 64:28, 1989.

Stevens DA: Coccidioidomycosis. N Engl J Med 332:1077, 1995.

Urschel HC Jr, et al: Sclerosing mediastinitis: improved management with histoplasmosis titer and ketoconazole. Ann Thorac Surg 50:215, 1990.

Urschel JD, Urschel DM: Mediastinal amyloidosis. Ann Thorac Surg 67:944, 2000.

Wiersema MJ, Chak A, Wiersema LM: Mediastinal histoplasmosis: evaluation with endosonography and endoscopic fine-needle biopsy. Gastrointest Endosc 40:78, 1994.

Yoshioka K: Mediastinal lymphadenopathy preceding skin and lung fibrosis in systemic sclerosis. Respiration 61:169, 1994.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 203