The Mediastinum

Editors: Shields, Thomas W.; LoCicero, Joseph; Ponn, Ronald B.; Rusch, Valerie W.

Title: General Thoracic Surgery, 6th Edition

Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

> Table of Contents > Volume II > The Mediastinum > Section XXIX - Primary Mediastinal Tumors and Syndromes Associated with Mediastinal Lesions > Chapter 180 - Transcervical-Transsternal Maximal Thymectomy for Myasthenia Gravis

Chapter 180

Transcervical-Transsternal Maximal Thymectomy for Myasthenia Gravis

Alfred Jaretzki III

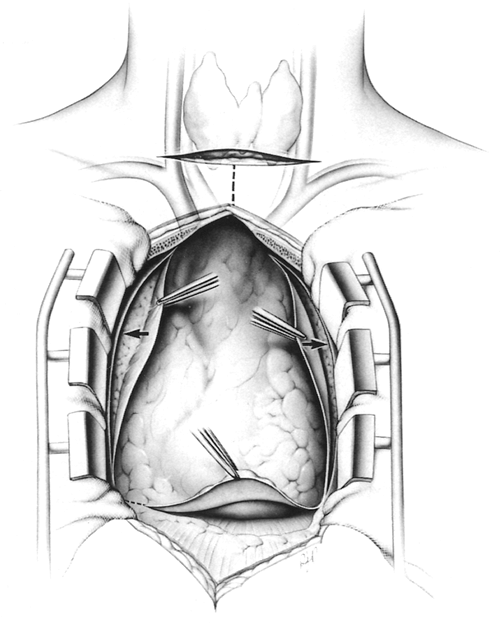

Removal of the entire thymus remains the goal of thymectomy in the treatment of autoimmune nonthymomatous myasthenia gravis (MG). On the basis of what is now known to be the anatomic extent of the thymus (see Fig. 181-1), a comprehensive resection is required. The combined transcervical-transsternal maximal thymectomy procedure (T-4), employing wide exposure in the neck and mediastinum, routinely and predictably accomplishes this goal. This procedure has been labeled by Cooper and co-workers (1989) as the benchmark against which the other resectional procedures should be measured. A photograph of a typical maximal thymectomy specimen confirms the extent of this resection (Fig. 180-1).

In comparing the alternate methods of thymectomy with the combined transcervical-transsternal maximal thymectomy, taking into account the known anatomy of the thymus, it seems almost certain that with incomplete exposure, minimally invasive resections are likely to be incomplete. A partial sternotomy, extracting the cervical portion of the thymus from below, the basic and extended transcervical procedures, or the various modifications of these resections, do not give sufficient access and exposure to predictably and safely remove all the tissue that may contain thymus. It is still too early to define the role of the video-assisted thoracoscopic procedures. However, at this date they also do not appear to predictably remove all tissue that may contain thymus.

Regardless of the surgical approach, however, injury to the phrenic, left vagus, and recurrent laryngeal nerves must be avoided since injury to these nerves can be especially devastating in the myasthenic patients. Accordingly, especially since it has not been unequivocally established that all microscopic thymus should be removed, it is preferable to leave behind potential thymus-bearing tissue than injure these nerves. This requirement increases the need for good surgical exposure and careful surgery, but may not justify selecting less than maximal surgical procedure.

OPERATIVE TECHNIQUE

All tissue is resected that anatomically contains thymus as has been shown by myself and Wolff (1988) to contain thymus (e.g., visible thymus, suspected thymus, and anterior cervical-mediastinal fat). The procedure is exenteration in extent and is performed as an en bloc dissection for a malignant tumor to ensure complete removal of all thymus-containing tissue and to avoid the potential for seeding of thymic tissue at the time of the procedure. My video (1996) depicts the operative procedure in detail, and is available. Based on the studies of Fukai and associates (1991), I believe videoscopic removal of the subcarinal fat should be added to this approach.

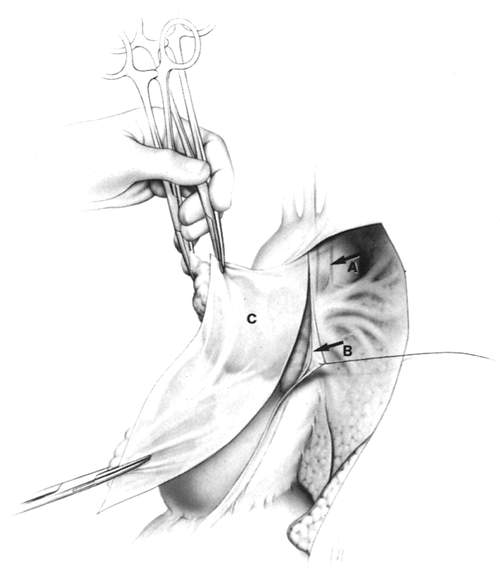

Exposure

Wide exposure in the neck and mediastinum is obtained, using a generous cervical incision and a complete median sternotomy (Fig. 180-2). The skin incisions may be kept separate for cosmetic considerations or may be combined into a T for better exposure. Either way, the cervical and mediastinal surgical fields are confluent (in continuity) below the subcutaneous level. The confluence of the two surgical fields has not been made clear previously. The T incision is routinely used for obese patients with short necks, for reoperations, and when large or malignant thymomas are present.

Initial Neck Incision

The cervical incision is generous, platysma flaps are elevated for wide exposure, and the strap muscles are mobilized. The remainder of the neck exploration and dissection is delayed until after the mediastinal dissection is completed.

|

Fig. 180-1. Photograph of the typical transcervical-transsternal maximal thymectomy specimen. The specimen consists of the en bloc resected cervical and mediastinal thymus, suspected thymus, and pretracheal and anterior mediastinal fat from thyroid isthmus to diaphragm with adherent mediastinal pleural sheets bilaterally. The specimen was divided after removal to indicate the division between the grossly visible thymus and the anterior mediastinal fat. |

P.2656

Mediastinal Incision and Dissection

A vertical skin incision is carried from within 2 to 3 cm of the sternal notch, or joined with the low collar incision into a T as noted previously, and caudad to the level of the xiphoid. A complete median sternotomy is performed.

The retrosternal portions of the strap muscles are then elevated and the lateral portions of the innominate vein and the internal mammary veins identified by bilaterally sweeping this portion of the thymus medially. Each sternal edge is then elevated, and the fat behind the sternal edges (to be removed with the specimen) is swept away from the incision (laterally) in order to expose the retrosternal portions of the mediastinal pleura.

Starting caudally, the mediastinal pleura which is now exposed just behind the sternum, is incised bilaterally from the level of the diaphragm to the thoracic inlet (see Fig. 180-2, arrows). Superiorly during this maneuver, care must be taken to avoid injury to the phrenic nerve and internal mammary vein since these structures are anterior at this level and close to the line of this incision. The sternotomy retractor is then inserted.

|

Fig. 180-2. Cervical and thoracic incisions. Wide exposure of the neck and mediastinum is obtained for complete safe removal of the thymus. A complete median sternotomy is performed. The skin incisions may be kept separate for cosmetic reasons or may be combined into a T for better exposure; either way, the cervical and mediastinal fields are confluent. The T incision is routinely used in obese patients with short necks, for reoperations, and when large or malignant thymomas are present. Arrows indicate initial anterior pleural incisions. From Jaretzki A III, Wolff M: Maximal thymectomy for myasthenia gravis: surgical anatomy and operative technique. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 96:711, 1988. With permission. |

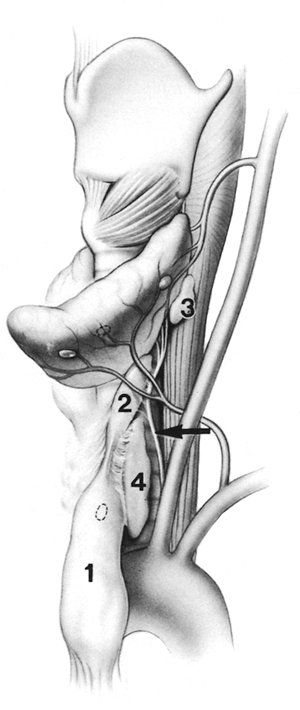

The mediastinal pleura is incised again, this time posteriorly, approximately 1 cm anterior and parallel to the phrenic nerves (Fig. 180-3). To facilitate this incision, starting superiorly, where the pleural incision is to be made, the mediastinal pleura is first carefully and bluntly separated from the underlying thymus with closed Metzenbaum scissors at this site. If the thymus is removed and the mediastinal pleural sheets are left in the patient, or these sheets are separated from the underlying thymus, microscopic thymus will be left on the mediastinal pleura.

The mediastinal pleura posterior to this second pleural incision, with the adherent phrenic nerve, is then elevated

P.2657

and teased away from the underlying thymo-fatty tissue. If possible, the artery accompanying the nerve is preserved, because it may be important to nerve function, as noted by Abd and colleagues (1989). The small phrenic vessel branches are divided using mini-clips, not unipolar cautery, to avoid thermal injury to the nerves. During the superior portion of this dissection on the left, the phrenic nerve must be exposed and protected (Fig. 180-3B). The location of the left vagus nerve must also be noted and this nerve also avoided (Fig. 180-3A); it lies 1 to 2 cm posterior to the phrenic nerve and contains the recurrent laryngeal nerve at this level. Throughout this portion of the dissection, extreme care must be taken to avoid injury to the nerves.

|

Fig. 180-3. Posterior mediastinal incision, anterior to phrenic nerves. A. Note location of the vagus nerve, 1 to 2 cm posterior to the phrenic nerve; it contains the recurrent nerve at this level. B. Phrenic nerves are elevated and teased off underlying thymo-fatty tissue bilaterally; the accompanying phrenic artery is preserved. C. The mediastinal pleural sheet is removed in continuity with the underlying adherent thymus. From Jaretzki A III, Wolff M: Maximal thymectomy for myasthenia gravis: surgical anatomy and operative technique. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 96:711, 1988. With permission. |

Starting at the level of the diaphragm and using sharp dissection on the pericardium (Fig. 180-4) (not blunt dissection, which leaves microscopic thymus on the pericardium), an en bloc dissection is undertaken from diaphragm to innominate vein, and from hilum to hilum. The fingers of pericardium that enter the thymus must be divided and included in the specimen to remain in the correct plane; this is well demonstrated in my video (1996). All thymus, suspected thymus, and mediastinal fat, including both mediastinal pleural sheets, are removed en bloc. Included in this portion of the specimen are: (a) all encapsulated and unencapsulated thymic lobes without individual identification; (b) the anterior mediastinal and pericardiophrenic fat; (c) the thymo-fatty tissue behind and beyond the phrenic nerves, lying in the sulcus between the cava and the ascending aorta on the right, behind the innominate vein, and lying in the region of the aortopulmonary window on the left; and (d) the tissue removed from the cervical portion of the dissection, as subsequently developed.

|

Fig. 180-4. Sharp dissection is performed on the pericardium, from diaphragm to innominate vein and from hilum to hilum. The specimen includes all the anterior mediastinal fat and the cardiophrenic fat pads; the thymo-fatty tissue under and beyond the phrenic nerves, in the aortopulmonary window and the aortocaval groove, and under the innominate vein; and both sheets of mediastinal pleura. Arrows indicate the anterior and posterior mediastinal pleural incisions on the right. Thymus has been mobilized from under the phrenic nerve on the left. From Jaretzki A III, Wolff M: Maximal thymectomy for myasthenia gravis: surgical anatomy and operative technique. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 96:711, 1988. With permission. |

The thymus is then separated from the innominate vein by sharp dissection, and the thymic veins are divided using clips or ties. The mediastinal dissection above the innominate vein is completed by elevating the strap muscles at this level, sweeping the thymic lobes medially, and then dissecting them off the lower portion of the innominate artery. At this point, laterally and bilaterally and only at this point, the dissection is adjacent to the capsule of the thymus.

Completion of Cervical Dissection

The cervical dissection is then undertaken. This requires experience in neck surgery to avoid recurrent nerve injury and preserve the parathyroid glands. The en bloc mobilization cephalad to the innominate artery is resumed, posterior

P.2658

to the strap muscles, medial to the recurrent nerves, and anterior to the trachea. The anatomic relationship of the cervical thymus and its variations, the parathyroid glands, and the recurrent laryngeal nerves is illustrated in Fig. 180-5.

|

Fig. 180-5. The anatomic relationship of the cervical thymus and its variations, the parathyroid glands, and the recurrent laryngeal nerves. (1) cervical portion of left cervical-mediastinal lobe containing a possible intrathymic parathyroid; (2) thymus superior to the fibrous cord, which may be continuous or discontinuous; (3) an accessory thymic lobule behind the superior lobe of the thyroid; (4) an accessory lateral cervical thymic lobe. Arrow indicates relationship of thymus to recurrent nerve. To ensure complete safe removal of these variations, wide exposure is required. To avoid injury to recurrent laryngeal nerves, both should be identified. From Jaretzki A III, Wolff M: Maximal thymectomy for myasthenia gravis: surgical anatomy and operative technique. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 96:711, 1988. With permission. |

The strap muscles are elevated from the level of the thyroid cartilage to the sternum, the thyroid lobes are elevated from their beds, and both recurrent laryngeal nerves are identified to avoid injury. Again, it is preferable to leave potential microscopic foci of thymus than to injure the nerves. The fibrous cords, which are often assumed to represent the cephalad termination of the thymus, are traced to their cephalad termination or, as occurs in 20% of cases, into additional thymic lobes that may extend to the level of the hyoid bone. Thymic tissue is sought behind and superior to the thyroid gland and adjacent to the vagus nerves.

The inferior parathyroid glands should be preserved if possible. However, one or both may lie within the superior poles of the cervicomediastinal lobes (see Fig. 181-1A,B) of the thymus and therefore may have been removed unknowingly. Accordingly, it is important to preserve both superior parathyroid glands. When it is difficult to distinguish a small thymic lobule from a large parathyroid gland, a biopsy sample is taken for frozen section.

The thyroid isthmus is usually resected to expose the second tracheal ring, making it easier to perform a tracheostomy postoperatively should it be necessary. Concurrent thyroid resection may be performed for a solitary nodule, which might contain thymus, or for nodular goiter or thyrotoxicosis, if indicated.

Wound Closure

The sternum is closed first. This may require special techniques, such as vertical wires incorporated within the transverse closure wires, for patients with healing problems secondary to corticosteroid administration. Before sternal closure, chest tubes are placed bilaterally, thorough irrigation with saline is performed, and complete expansion of both lungs is ensured. Following closure of the sternum, the subcutaneous area is thoroughly irrigated with saline to remove the free lobules of fat. The neck incision is then closed in layers.

Tracheostomy

A tracheostomy must not be performed at the time of transcervical-transsternal maximal thymectomy because of the communication that exists between the neck, mediastinum, and both pleural spaces. If a tracheostomy is required within the first 14 postoperative days, a two-stage procedure should be performed. Accordingly, if it is anticipated that a tracheostomy will be required postoperatively, the first stage should be performed at the time of the thymectomy.

At the first stage, after the thyroid isthmus is removed, a suture is placed in the second tracheal ring for identification later and multiple sutures are placed inferiorly to separate the cervical from the mediastinal wound. A small separate skin incision is made superior to the previous neck incision, directly over the second tracheal ring, or is made first if the first stage is being performed postoperatively. The superior cervical wound is then packed with 1-inch dry packing to promote a seal between the cervical and mediastinal wounds. This packing is prevented from sliding into the mediastinum by the previously placed sutures caudad to this site. Both cervical incisions are then closed.

At the second stage, 72 to 96 hours later, the small cervical incision overlying the second tracheal cartilage is

P.2659

opened, the packing removed, and the tracheostomy is completed. Before incising the trachea itself, however, this wound should be filled with saline to ensure that a seal exists separating the cervical from the mediastinal wounds. If the saline disappears, demonstrating that a seal has not been established, the wound is repacked and closed, and the tracheostomy is postponed at least another 48 to 72 hours.

If a tracheostomy is in place at the time of thymectomy, the entire cervical thymus cannot be removed at this time. The patient is ventilated during surgery with an oral endotracheal tube. As the endotracheal tube passes the vocal cords, the tracheostomy tube is removed. The tracheostomy wound is then packed and sealed with a rubber dam and glue to protect the sternotomy wound from bacterial contamination. The sternotomy field is then prepared and draped. The mediastinal portion of the thymectomy is then performed through the sternal incision. As much intracapsular thymus in the neck as possible is extracted from below, but entrance into the tracheostomy tract must be meticulously avoided.

To complete the thymectomy under these circumstances, these patients must have a neck exploration and dissection, as previously described, at a later date when the tracheostomy is no longer needed, the tracheostomy has been removed, and the inflammatory reaction in this wound has completely abated.

INDICATIONS FOR THYMECTOMY

It is not surprising that neurologists hold differing views, as noted by Lanska (1990), as to when, and even if, a thymectomy is indicated in the treatment of autoimmune nonthymomatous MG, in view of the variable thymic resections with apparent variable responses, and the conflicting analysis of data (see Chapter 181). Keesey's (1998) algorithm, in reference to moderate generalized MG, represents a centrist position in the treatment of adult patients. He stated in part:

Thymectomy is recommended for those relatively healthy patients whose myasthenic symptoms interfere with their lives enough for them to consider undergoing major thoracic surgery. While it is expensive and invasive, thymectomy is the only treatment available that offers a chance of an eventual drug-free remission [the italics are his]. The age at which the risks outweigh the potential benefits must be individualized for every patient.

Of note, Keesey's group routinely performs the aggressive extended transsternal thymectomy described by Mulder (1996).

Based on the Columbia Presbyterian Medical Center (CPMC) experience with the combined transcervical-transsternal maximal thymectomy used by myself and co-workers (1988) and the interpretation of the available data (Chapter 181), I consider this to be the procedure of choice, assuming the surgeon is experienced in neck surgery. At the least, I recommend that an aggressive extended transsternal thymectomy be considered for most adult patients with more than very mild generalized autoimmune nonthymomatous MG. Thymectomy should be undertaken regardless of the duration of symptoms or age of the patient. In my and co-workers' (1988) experience, patients with symptoms of many years as well as those over the age of 50 responded equally well, perhaps related to the extent of the resection. The patient's medical condition has to be satisfactory for the planned operation and patient selection over the age of 65 has to be selective. In addition, in my opinion, thymectomy should be undertaken in virtually all patients (unless a specific contraindication exists) with respiratory or oropharyngeal symptoms, including those with mild weakness as defined by the Myasthenia Gravis Task Force's Recommendations for Clinical Research Standards published by myself and collaborator (2000).

In the CPMC series of combined transcervical-transsternal maximal thymectomy (T-4), as reported by myself and associates (1988), the remission rate was independent of the duration of symptoms or age of the patient. Contrary to the belief that the thymus disappears with age, thymus was found in all patients in that series, as well as those who underwent subsequently (to age 75 years), and thymic tissue was also found in all 10 specimens in an autopsy study of aging individuals without MG (ages 60 to 90 years). In this same series, as reported by Soliven and colleagues (1988), the results were equally good for seronegative patients, possibly because of the presence of antibodies to other proteins of the neuromuscular junction, as described by Hoch and associates (2001).

Although the role of thymectomy for patients with purely ocular symptoms is less well defined, as noted by Evoli (2001) and Schumm (1985) and their associates, it is probably indicated for patients in whom the ocular MG interferes with lifestyle or work, and when immunosuppressive therapy is contraindicated or not effective. Thymectomy within the first year of the illness in adults, or early thymectomy, has been recommended by DeFilippi (1994), Monden (1984), and Rubin (1981) and their colleagues, but lacks prospective documentation at this time. The indication for thymectomy in children is a separate issue which has been addressed by Adams (1990), Andrews (1998), Rodriguez (1983), and Seybold (1998) and their co-workers.

PATIENT MANAGEMENT

These patients should be managed by a team of neurologists, pulmonologists, respiratory therapists, intensive care specialists, anesthesiologists, and surgeons in an institution with experience and expertise in the care of patients with MG.

Preoperative preparation should include a detailed evaluation of the pulmonary function status, before and after

P.2660

cholinergic inhibitors, if the patient is receiving this medication and can tolerate its withdrawal for the 12 hours necessary to perform the before and after study. As emphasized by Younger and co-workers (1984), this evaluation should include measurements of respiratory muscle forces. The maximum expiratory force, which is also an excellent measure of cough effectiveness so vital postoperatively, is more reliable than vital capacity in predicting postoperative problems in these patients. A force below 40 to 50 cm H2O indicates a potential for postoperative respiratory complications.

The patients should be as free of weakness as possible at the time of the surgical procedure, especially free of oropharyngeal and respiratory weakness, using plasmapheresis or intravenous immunoglobulin, and even immunosuppression if necessary, to achieve this goal. One should not rely on cholinesterase inhibitors (Mestinon, ICN Pharmaceuticals, Costa Mesa, CA, U.S.A.) to achieve this state in the preoperative preparation of these patients since such therapy only temporarily masks the symptoms and does not alter the underlying process. Importantly, if cholinesterase inhibitors alone are used preoperatively to control respiratory and oropharyngeal weakness, respiratory and oropharyngeal weakness may flare up postoperatively, may not respond to cholinesterase inhibition, and may become a serious problem.

Postoperatively, these patients should be managed in an intensive care setting for close observation so that emergency reintubation and respiratory support is immediately available and can be instituted at any time without delay for early signs of fatigue, progressive weakness, or impending respiratory failure.

RESULTS

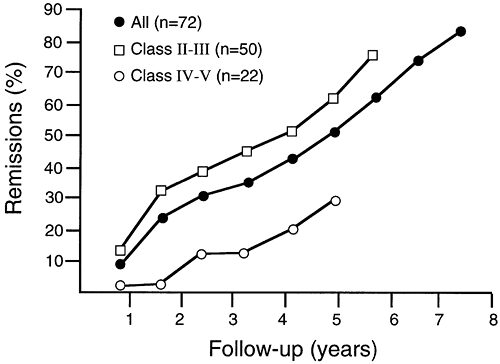

The results of the combined transcervical-transsternal maximal thymectomy for autoimmune nonthymomatous generalized MG that I and co-workers (1988) reported are impressive and appear to be superior to those that follow less comprehensive resections (see Chapter 181). Seventy-two patients (27 men and 45 women) with generalized MG, ages 16 to 66 years (32% were older than 35), were evaluated. Using the CPMC maximum severity classification, which closely approximates the Myasthenia Gravis Task Force's clinical classification subsequently developed and reported by myself and colleagues (see Table 181-1), approximately 80% of the patients had moderately severe or severe weakness and 12.5% had been in crisis. The mean duration of preoperative symptoms was 2.8 (0.1 20) years. The mean follow-up was 3.4 (0.5 7.4) years. Remission at that time was defined as no signs, no symptoms, and no medication for at least 6 months.

Life table analysis for this patient cohort (Fig. 180-6) predicts a remission rate of 81% when all patients have been followed for 7.5 years; the milder the symptoms and the longer the patients are followed, the better the results. Using hazard analysis, there were 13.9 remissions per 1,000 patient-months. Subsequent to this report, a recurrence of symptoms after the initial remission has occurred in two patients (3%), one temporary and one prolonged. Age, sex, the presence or absence of microscopic hyperplasia, or the presence or absence of measurable receptor antibodies did not influence the results following maximal thymectomy in this cohort of patients. However, in a separate group of patients, the presence of a thymoma, whether or not invasive, frequently influenced the results unfavorably.

I no longer report uncorrected crude data (the number of remissions divided by the number of patients who underwent surgery or divided by the number of patients followed) because crude data comparisons are not valid. However, when the crude data are corrected for mean length of follow-up (see Fig. 181-4), an analysis that does not correct for patients lost to follow-up among other shortcomings, the remission rate at a mean follow-up of 7.4 years is 62%.

Until suitably designed prospective studies demonstrate otherwise, these results should serve as the benchmark for evaluation of thymectomy techniques. Although the median sternotomy and scar associated with transsternal approaches are certainly less desirable than those of the transcervical and the video-assisted thoracic surgical procedures, and the postoperative stay is usually several days longer, the risks and morbidity associated with a transsternal thymectomy, whatever the extent, are now minimal. Accordingly,

P.2661

results should be the determining factor in selecting the thymectomy technique. Furthermore, although the initial hospital costs for the transsternal and combined transcervical-transsternal procedures may be more as compared with the other techniques, if subsequent fewer hospitalizations and fewer intensive care stays occur, the overall costs and disability will be less. Although intuitively one may presume that the more aggressive resections should thereby prove their worth, a controlled prospective long-term cost-benefit analysis, in addition to survival-remission analysis, is needed to resolve this issue.

|

Fig. 180-6. Life table analysis remission rates after maximal thymectomy for nonthymomatous myasthenia gravis. The predicted remission rate is 81% when all patients have been followed for 7.5 years. The remission rate is greater for patients in classes II and III (mild and moderate symptoms) compared with those in classes IV and V (severe symptoms and crisis). The differences are statistically significant (p = 0.04). Modified from Jaretzki A III, et al: Maximal thymectomy for myasthenia gravis: results. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 95:747, 1988. With permission. |

REOPERATION

As recommended by Kirschner (2001), the concept of reoperation for an unsatisfactory result after one of the more limited resections should be accepted. This recommendation appears to be straightforward when applied to a patient who still has, or progresses to, an incapacitating and poorly controlled illness. If repeated hospitalizations and intensive care unit stays have been required 3 to 5 or more years following a basic transcervical thymectomy, a standard transsternal thymectomy, or one of the video-assisted thoracoscopic procedures.

It is more difficult to recommend reoperation for less severe symptoms or after more aggressive operations, but appropriate in selected instances. Unfortunately at this time, it is not possible to determine the location, or even presence, of even moderate amounts of residual thymus prior to the original surgery or reoperation, or even by gross inspection at the time of surgery. Unfortunately, computed tomographic (CT) scans, magnetic resonance (MR) examinations, and antibody studies are usually not helpful. However, a review of the operative notes and pathologic report of the original surgical procedure usually makes it clear that an incomplete resection had been performed. The timing of reoperations is also a difficult decision. Although a 3- to 5-year wait seems prudent, as I reported (2002), it is occasionally appropriate to reoperate earlier and sometimes many years later.

If reoperation is undertaken for persistent or recurrent symptoms, it should be as aggressive as the combined transcervical-transsternal maximal technique (T-4) both in the neck and mediastinum, regardless of the earlier procedure, to ensure that all residual gross and microscopic thymus is removed. It is illogical to limit the reoperation procedure to a repeat transcervical approach as Cooper (1989) and Papatestas (1989) and associates have done, to a repeat limited transsternal approach as Cooper (1989) and Rosenberg (1986) and their colleagues have done, to a repeat thoracoscopic approach as Pompeo and co-workers (2002) have done, or even to a repeat extended transsternal resection without a standard neck dissection as Masaoka and co-workers (1982) have done. Incomplete resections at reoperations may explain the occasional failure to find thymus or lack of benefit, as reported by Papatestas and associates (1989).

Table 180-1. Reoperation for Nonthymomatous MG Following Previous Basic Transcervical and Standard Transsternal Thymectomy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In my and associates' (1988) experience with 15 patients whose original thymectomy was a basic transcervical (T-1a)or a standard transsternal (T-3a) resection, residual thymus was found in all (Table 180-1). As I reported later (2002), all patients subsequently benefited, some dramatically. At the time of the relatively short follow-up, approximately 50% of this cohort had minimal manifestations (MM-3) or less (see Table 181-4).

THYMOMA

Ordinarily a complete median sternotomy is the incision of choice when a thymoma is present, regardless of the location or size of the thymoma, because wide local excision is required to avoid local recurrences. Occasionally, when additional exposure is required, an anterior or posterolateral thoracotomy or clamshell incision is performed in addition to the initial median sternotomy. Whether or not MG is present, in view of the potential for the subsequent onset of MG, extensive removal of thymic tissue in the mediastinum and neck is indicated and should be performed en bloc with the thymoma.

However, if preoperatively the presence of MG has been excluded by appropriate testing, which should include pulmonary function evaluation, and if the mediastinal dissection

P.2662

has been extensive and time consuming, consideration can be given to omitting the neck exploration with the clear understanding that should the patient develop MG in the future, a neck dissection would become mandatory. Furthermore, if the diagnosis of thymoma is confirmed preoperatively and the tumor is large or invasive or pleural implants exist, preoperative chemotherapy or irradiation, or a combination of both, should be considered, including the administration of chemotherapy first so its effect can be evaluated.

The use of a double-lumen endotracheal tube is required so that at the initial exploration, palpation and visualization of both pleural spaces and the diaphragms for possible tumor implants can be readily performed. Invaded or even adherent pericardium, lung, innominate vein, retrosternal portions of strap muscles, or posterior sternal periosteum are removed en bloc with the specimen. Removal of the superior vena cava, if involved, may be considered if gross resection of all the tumor appears achievable and the patient can tolerate the more extensive procedure. Removal of a phrenic nerve segment may present a serious problem to a patient with MG, unless a nerve graft is performed, because of the presence, or potential, for compromised respiratory function. Accordingly, adherence or invasion of a phrenic nerve by tumor presents a difficult decision for which there is no simple answer. A decision needs to be made whether to peel the tumor off the nerve (often the most appropriate maneuver), simply resect a portion of the nerve (especially if it is already nonfunctional), or perform a nerve resection and graft as described by Schoeller and associates (2001), taking into account the patient's pulmonary function status, the functional status of the nerve, and, importantly, the local and distant extent of the tumor with chances of a cure.

CONCLUSION

The combined transcervical-transsternal maximal thymectomy remains my choice when thymectomy is undertaken for MG, and it is my hope that more institutions will become skilled in the performance of this procedure. This recommendation is supported by Bulkley and colleagues (1997). In the quoted personal communication to Newsom-Davism (see Chapter 181), Rowland commented, I have no idea why surgeons are unwilling to do maximal thymectomies. It is also of note that starting in 1978, when maximal thymectomies were first performed at the CPMC in New York City, Rowland regularly recommended a maximal thymectomy (T-4) for patients with generalized MG.

There are some important caveats, however. This recommendation is only applicable if the surgeon is willing to take the time to remove all available thymus and do this safely without nerve injury. For a thoracic surgeon to undertake the cervical portion of this dissection, it may be appropriate to request the assistance of a surgeon experienced in surgery of the neck.

It is hoped, however, that the day will come when some form of targeted nonsurgical therapy, with no significant side effects, produces long-term remissions in these patients. At that time, thymectomy in any form, especially the procedure that produces arguably the most complete resection, will be regarded as barbaric. Until such time arrives, however, as complete a removal of the thymus as can be achieved safely and without nerve injury should be considered an integral part of the therapy for MG.

Twenty-six years ago, the Mayo Clinic group, as reported by Buckingham and co-workers (1976), made basically the same statement: It seems likely that future discoveries will permit the management of MG without surgical intervention but, for the present, the beneficial role of thymectomy for these unfortunate patients has been clearly demonstrated. Amen.

REFERENCES

Abd AG, et al: Diaphragmatic dysfunction after open heart surgery: treatment with a rocking bed. Ann Intern Med 111:881, 1989.

Adams C, et al: Thymectomy in juvenile myasthenia gravis. J Child Neurol 5:215, 1990.

Andrews PI: A treatment algorithm for autoimmune myasthenia gravis in children. Ann NY Acad Sci 841:789, 1998.

Buckingham JM, et al: The value of thymectomy in myasthenia gravis: a computer-assisted matched study. Ann Surg 184:453, 1976.

Bulkley GB, et al: Extended cervicomediastinal thymectomy in the integrated management of myasthenia gravis. Ann Surg 226:324, 1997.

Cooper J, et al: Symposium: thymectomy for myasthenia gravis. Contemp Surg 34:65, 1989.

DeFilippi VJ, Richman DP, Ferguson MK: Transcervical thymectomy for myasthenia gravis. Ann Thorac Surg 57:194, 1994.

Evoli A, et al: Therapeutic options in ocular myasthenia gravis. Neuromuscul Disord 11:208, 2001.

Fukai I, et al: Distribution of thymic tissue in the mediastinal adipose tissue. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 101:1099, 1991.

Hoch W, et al: Auto-antibodies to the receptor tyrosine kinase MuSK in patients with myasthenia gravis without acetylcholine receptor antibodies. Nat Med 7:365, 2001.

Jaretzki A III: Transcervical-transsternal maximal thymectomy for myasthenia gravis [video]. Society of Thoracic Surgeons' Film Library, 1996. PO Box 809285, Chicago, IL 60680 9285.

Jaretzki A III: Thymectomy. In Kaminski HJ (ed): Myasthenia Gravis and Related Disorders. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press, 2002, p. 325

Jaretzki A III, Wolff M: Maximal thymectomy for myasthenia gravis. Surgical anatomy and operative technique. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 96:711, 1988.

Jaretzki A III, et al: Maximal thymectomy for myasthenia gravis. Results. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 95:747, 1988.

Jaretzki A III, et al: Myasthenia gravis: recommendations for clinical research standards. Task Force of the Medical Scientific Advisory Board of the Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America. Neurology 55:16, 2000.

Keesey JC: A treatment algorithm for autoimmune myasthenia in adults. Ann NY Acad Sci 841:753, 1998.

Kirschner PA: Reoperation on the thymus. A critique. Chest Surg Clin North Am 11:439, 2001.

Lanska D: Indications for thymectomy in myasthenia gravis. Neurology 40:1828, 1990.

Masaoka A, et al: Reoperation after transcervical thymectomy for myasthenia gravis. Neurology 32:83, 1982.

P.2663

Monden Y, et al: Effects of preoperative duration of symptoms on patients with myasthenia gravis. Ann Thorac Surg 38:287, 1984.

Mulder DG: Extended transsternal thymectomy. Chest Surg Clin North Am 6:95, 1996.

Papatestas AE, et al: Symposium: thymectomy for myasthenia gravis. Contemp Surg 34:65, 1989.

Pompeo E, et al: Thoracoscopic completion thymectomy in refractory nonthymomatous myasthenia. Ann Thorac Surg 70:918, 2002.

Rodriguez M, et al: Myasthenia gravis in children: long-term follow-up. Ann Neurol 13:504, 1983.

Rosenberg M, et al: Recurrence of thymic hyperplasia after trans-sternal thymectomy in myasthenia gravis. Chest 89:888, 1986.

Rubin JW, et al: Factors affecting response to thymectomy for myasthenia gravis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 82:720, 1981.

Schoeller T, et al: Successful immediate phrenic nerve reconstruction during mediastinal tumor resection. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 122:1235, 2001.

Schumm F, et al: Thymectomy in myasthenia with pure ocular symptoms. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 48:332, 1985.

Seybold ME: Thymectomy in childhood myasthenia gravis. Ann NY Acad Sci 841:731, 1998.

Soliven BC, et al: Seronegative myasthenia gravis. Neurology 38:514, 1988.

Younger DS, et al: Myasthenia gravis: determinants for independent ventilation after transsternal thymectomy. Neurology 34:336, 1984.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 203