150 - Carcinoma of the Esophagus

Editors: Shields, Thomas W.; LoCicero, Joseph; Ponn, Ronald B.; Rusch, Valerie W.

Title: General Thoracic Surgery, 6th Edition

Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

> Table of Contents > Volume II > The Mediastinum > Section XXIX - Primary Mediastinal Tumors and Syndromes Associated with Mediastinal Lesions > Chapter 176 - Standard Thymectomy

Chapter 176

Standard Thymectomy

Francis C. Nichols III

Sina Ercan

Victor F. Trastek

HISTORY

The history of the identification of the characteristics of an initially puzzling neuromuscular disorder, now known as myasthenia gravis (MG), and its relationship to the thymus has been recorded succinctly by Kirschner (2000). We believe it is worthwhile to quote it in part as the introduction to our presentation of the use of a standard transsternal thymectomy in the surgical management of this disease:

With the exception of an isolated case report in 1672 by Willis and forgotten until unearthed by Guthrie in 1903, the current knowledge of the clinical picture of myasthenia gravis begins a little over a century ago. Wilks, also of England, in 1877 described a case of a young woman with now recognizable typical symptoms, who died of acute respiratory paralysis and who, at autopsy, had no central nervous system lesion. Much of the ensuing knowledge was provided by the German school of neurologists. Erb (1879) encountered three patients with bulbar symptoms, ptosis, and weakness of neck muscles one of them had a spontaneous remission followed by relapse and sudden death. Oppenheim (1899, 1901) made similar observations and again emphasized the absence of central nervous system disease. Goldflam of Warsaw (1893), working in Germany and with Charcot in Paris, recognized that the previously reported cases as well as several of his own represented a distinct clinical entity. Because of his comprehensive exposition and Erb's pioneer observations, the disorder came to be known as the Erb-Goldflam symptom-complex. Jolly (1895) described the typical decremental response of affected muscles to repetitive tetanic stimulation now known as the Jolly test. He even theorized though he never followed through that physostigmine might be used therapeutically! He suggested that the condition be called myasthenia gravis pseudoparalytica. In 1899 the Berlin Society for Neurology and Psychiatry shortened the name to myasthenia gravis, by which it has been known ever since. The etymology of the name is hybrid, being derived from the Greek mys = muscle, and aesthenia = weakness and the Latin gravis = severe. This discrepancy foreshadowed the innumerable inconsistencies and controversies that persist up to the present day. Campbell and Bramwell (1900) summed up the knowledge accumulated up to that time with the details of 60 published cases, 23 of which ended fatally. They even speculated that the disease is due to a poison probably of microbic origin acting upon the lower motor neurons and interfering with their functional activity without necessarily producing discoverable change in structure. The first associations of myasthenia gravis with thymic disease were made by Oppenheim (1899) and Weigert (1901), who described tumors of the thymus at autopsy.

Following the report by Alfred Blalock and associates (1939) of successful resection of the thymus in a 26-year-old woman with MG and a thymic cyst, surgical resection of the thymus became a treatment option for this disease. In 1944, Blalock published a total of 20 cases of MG treated by a transsternal thymectomy but raised some questions as to its efficacy; however, he noted that young women with a short duration of MG had the best results from thymectomy. In the following decade, numerous studies from England by Keynes (1943, 1955) and in the United States by Clagett and Eaton (1947) at the Mayo Clinic, as well as a later report by Eaton and Clagett (1955), and by Sweet and Cope in Boston as reported by Schwab and Leland (1953), continued the debate as to the role of thymectomy in treating MG. With the passage of time and the refinement of perioperative care, the results of thymectomy improved so as to validate the benefit of the operation as a significant part of the overall treatment of the myasthenic patient.*

Nonetheless, the thymus continues to present a challenge to the thoracic surgeon not only as a structure that may affect neuromuscular conduction, but also as the origin of both benign and malignant neoplasms. Controversy exists regarding early versus late surgery for MG, and which operative technique is best suited for removal of the thymus gland. Thymectomy through a partial sternotomy remains our approach of choice for patients with MG without thymoma. A full sternotomy is used in patients with thymoma.

P.2630

INDICATIONS

Indications for thymectomy include resection of a thymic mass, MG in selected patients, or both. Thymectomy is recommended for a patient with MG if medical treatment fails, for a young patient with symptoms of short duration, and for a patient who experiences significant disability from the medications. Patients with ocular symptoms alone or those with symptoms well controlled on medication are not currently believed by us to be candidates for thymectomy.

EVALUATION

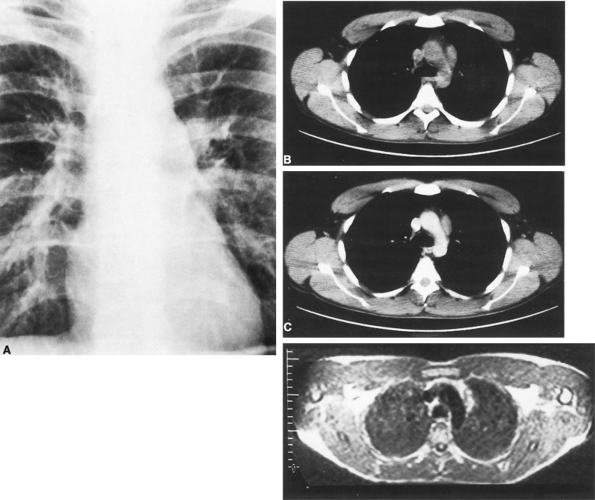

Preoperative evaluation of a patient with an anterior mediastinal mass should include computed tomography (CT) with contrast enhancement to rule out vascular structures and to better delineate any mediastinal mass (Fig. 176-1). Magnetic resonance (MR) imaging may accomplish these same goals (Fig. 176-1D). Transthoracic needle aspirates are controversial but may be helpful in the diagnosis of thymoma. If a patient presents with an anterior mediastinal mass suspicious for thymoma and vascular abnormalities have been ruled out, then resection is indicated. Additionally, preoperative evaluation should be directed toward the detection of associated MG. Likewise, those patients being considered for thymectomy because of MG should have preoperative chest CT or MRI, searching for an associated thymoma.

|

Fig. 176-1. Radiographic manifestations of thymoma. A. Projection of a solid tumor from the mediastinum into the left hemithorax on posteroanterior radiography. B. CT without contrast medium indicates that the lesion lies in the anterior mediastinum. C. Contrast medium injection through the veins shows that the tumor is not directly related to the vascular tree, essentially ruling out aneurysm. Relationships to other structures, such as pericardium and lung, are delineated. D. MR imaging of the same tumor provides similar information as computed tomography but can be performed without contrast medium. |

THYMECTOMY VIA A PARTIAL MEDIAN STERNOTOMY

Preoperative Preparation

Patients undergoing thymectomy for MG are candidates for operation only if their medical condition is optimal. If the patient cannot be stabilized with medication, then preoperative plasmapheresis is required before thymectomy.

P.2631

Today, patients with bulbar-type symptoms or who are poorly controlled on medication undergo preoperative plasmapheresis to diminish perioperative complications and the risks for myasthenic crisis. In a prospective study to determine if preoperative plasmapheresis was of benefit in patients undergoing thymectomy, Seggia and associates (1995) found that plasmapheresis significantly improved respiratory function and muscle strength, which lead to reduced hospital stay and cost. The team approach to the care of the patient cannot be overly stressed, with anesthesia, neurology and the surgical team actively involved and interacting throughout the entire perioperative period. Preoperative medication is minimal, usually consisting only of atropine and a mild sedative. Preoperative anticholinergic medications are avoided. Myasthenic patients pose no particular anesthetic problem, although muscle relaxants should be avoided. Deep anesthesia is maintained by an inhalation agent and short-acting narcotics. During the operative procedure, the airway and ventilation are controlled by a single-lumen endotracheal tube.

|

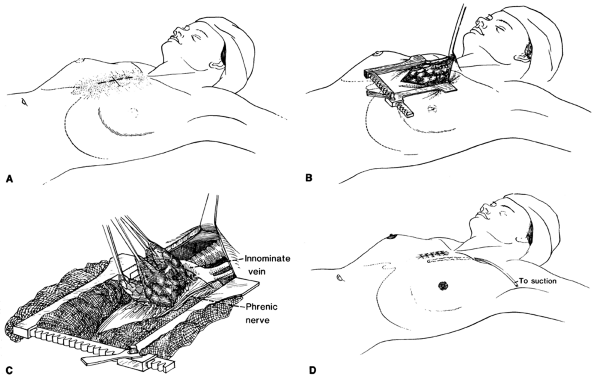

Fig. 176-2. Surgical exposure and thymectomy for myasthenia gravis. A. A short midline skin incision is carried to the third interspace, keeping well below the sternal notch. B. The manubrium and sternum are split to the third interspace, and the mediastinum is exposed by spreading the manubrium and retracting the incision cephalad. C. The entire thymus is freed from the adjacent pericardium and mediastinal pleura by blunt and sharp dissection. Care is taken to remove all thymic tissue, including cervical extensions, while carefully preserving the phrenic nerves. D. A stable, cosmetically acceptable incision results after closure of the wound. Drainage is by anterior mediastinal tube if pleural cavities have not been violated. A chest tube will be needed if the pleura was entered. |

Operative Technique

Approaches for thymectomy in patients with MG range from a video-assisted thoracoscopic approach, as advocated by Yim (1999) and Savcenko (2002) and their associates, to a transverse cervical incision, as Kirschner (1969), Cooper (1988), and Calhoun (1999) and their colleagues have advocated. Radical thymectomy through a complete sternotomy with cervical extension is advocated by Jaretzki (1997) and associates (1977, 1988). When a thymoma is not present, we prefer performing thymectomy using a partial upper sternal-splitting incision (Fig. 176-2A, B). Usually, the upper end of the skin incision is kept one to two finger breadths below the sternal notch and is carried to the level of the third or fourth interspace. The manubrium must be completely divided and the sternum divided to the level of least the third intercostal space. Through this relatively short skin incision, with the sternum separated, adequate visualization of the entire mediastinal portion of the thymus and its cervical extensions can be obtained. If a thymoma is

P.2632

suspected or found incidentally, a complete sternotomy is usually performed.

After entering the mediastinum, the anterior surface of the gland is exposed. By blunt and sharp dissection, the thymus is freed from the pericardium and adjacent mediastinal pleura (Fig. 176-2C). The right lower pole is mobilized by both blunt and sharp dissection and is then reflected cephalad. Once the lower horn is mobilized, the ipsilateral upper horn is freed up to the thyrothymic ligament, which is ligated and divided. The upper and lower horns are then pulled medially, exposing the constant arterial supply entering laterally from the internal mammary. The arterial blood supply is either cauterized or ligated and divided. The same maneuvers are repeated for the left lower and upper horns, respectively. This side can be more challenging because the phrenic nerve may be following a more intimate course with the lateral portion of the thymus gland. After mobilizing all four horns with the surrounding fat pads off the pericardium, the central venous drainage into the left innominate vein is isolated and ligated with silk ties. Hemoclips are not recommended because they may easily become dislodged, resulting in a mediastinal hematoma. Upper, lower, and lateral margins should be pathologically checked with frozen sections to ensure complete removal of all possible satellite thymic tissue. Throughout the operation, great attention visualizing and preserving the phrenic nerve is critical. After completion of the total thymectomy, a thoracostomy tube is placed from the right anterolateral chest wall and extending to the left apex by traversing the mediastinum. The sternum is approximated with steel wires, and the soft tissue and skin closed with absorbable sutures. The result is a relatively comfortable and cosmetically acceptable incision (Fig. 176-2D).

For patients with a thymic mass, a full sternotomy is usually needed to provide exposure. Once exploration for metastatic disease is completed, the tumor should be resected en bloc along with the entire thymus. At any point where adherence or invasion to a surrounding structure is suspected, en bloc resection of the adjacent structure with the thymic mass should, if possible, be performed. If the tumor cannot be removed entirely, a debulking procedure should be performed. Frozen sections during the operation help ensure tumor-free margins. The surgeon should carefully document any gross adherence or invasion present during the resection. Again, protection of the phrenic nerves is important; however, if curative resection requires removal of one phrenic nerve and the patient can tolerate this from a respiratory standpoint, it should be performed.

Postoperative Care

After the operation, the patient is awakened and evaluated closely by the anesthesiologist. Extubation is performed in the recovery room if the respiratory effort and blood gases are satisfactory. Nearly all patients can be extubated immediately. If the patient has MG, the patient is observed closely in the intensive care unit by the surgery, critical care, and neurology teams. Inspiratory-expiratory pressures and vital capacity are measured every 6 hours to evaluate respiratory status. Aggressive pulmonary toilet is maintained and ambulation initiated the day after surgery. Anticholinesterase agents are restarted only if weakness occurs. Undertreating with these agents immediately postoperatively minimizes problems with oral and tracheal secretions and decreases the possibility of cholinergic crisis. If the patient with MG develops respiratory problems despite this approach, plasmapheresis is instituted. Gracey and associates (1984a, 1984b) have described the successful use of plasmapheresis in treating ventilator-dependent patients with MG. Because many of our patients undergo preoperative plasmapheresis, postoperative plasmapheresis is rarely required. Once the patient's respiration is stable, the patient is transferred from intensive care to the general patient floor, and the drains are removed at the earliest possible time.

RESULTS

With the advent of a team approach combined with aggressive preoperative and postoperative care, operative mortality has been nearly eliminated. We reviewed 186 patients seen at the Mayo Clinic from 1982 to 1996 who underwent thymic resection. Of these 186 patients, 162 (87.1%) had MG. A partial sternotomy was performed in 146 patients and a full sternotomy in 40 patients. One hundred fifty-eight of the 162 patients with MG were extubated within the first few hours after the operation, and the remaining 4 were extubated the following day. Only one patient required reintubation. No operative deaths occurred, and the average length of hospitalization was a mean of 5.6 days. Major complications occurred in 4 (2.46%) of the patients (Table 176-1). Pathology included invasive thymoma in 7 patients, benign (noninvasive) thymoma in 25, fat-replaced gland in 32, hyperplastic gland in 62, and normal

P.2633

thymus glands in 36. Lewis and colleagues (1987) reported on 274 patients from 1941 to 1981 having surgical treatment for thymoma, of whom 227 had total resection. In this group there were seven deaths, for an operative mortality rate of 3.1%. Complications occurred in 89 (39.2%) of the patients, with most occurring in patients with MG or having prior cardiovascular disease. Although MG has in the past negatively influenced operative survival, with improved preoperative and postoperative care, especially preoperative plasmapheresis, this is no longer true.

Table 176-1. Thymectomy for Myasthenia Gravis, Mayo Clinic Series, 1982 through 1996 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

CONCLUSION

Thymectomy, through a partial sternotomy for MG, or a full sternotomy for a thymic mass or thymoma, provides excellent exposure and the ability to treat all aspects of the problem with low mortality and morbidity. Whether a more limited approach, such as video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) or cervical thymectomy, or a more aggressive approach, such as transcervical-transsternal maximal thymectomy, is more effective in the treatment of MG is difficult to prove. Protection of the phrenic nerves in patients with MG is paramount, and any approach used to remove the thymus must keep this in mind. Using a team approach, with careful preoperative evaluation, complete intraoperative resection and aggressive postoperative care, thymectomy can be safely performed.

REFERENCES

Blalock A: Thymectomy in the treatment of myasthenia gravis: report of twenty cases. J Thorac Surg 13:316, 1944.

Blalock A, et al: Myasthenia gravis and tumors of the thymic region. Report of a case in which the tumor was removed. Ann Surg 110:544, 1939.

Calhoun RF, et al: Results of transcervical thymectomy for myasthenia gravis in 100 consecutive patients. Ann Surg 230:555, 1999.

Campbell H, Bramwell E: Myasthenia gravis. Brain 23:277, 1900.

Clagett OT, Eaton LM: Surgical treatment of myasthenia gravis. J Thorac Surg 162:62, 1947.

Cooper JD, et al: An improved technique to facilitate transcervical thymectomy for myasthenia gravis. Ann Thorac Surg 45:242, 1988.

Eaton LE, Clagett OT: Present status of thymectomy in treatment of myasthenia gravis. Am J Med 19:703, 1955.

Erb W: Zur Casuistik der bulb ren Lahmungen. 3. Ueber einen neuen, wahrscheinlich bulb ren Symptomencomplex. Arch Psych Nervenkrankh 9:336, 1879.

Goldflam S: Ueber einen scheinbar heilbaren bulb ren paralytischen Symptomencomplex mit Beteiligung der Extremitaten. Dtsch Z Nervenheilk 4:312, 1893.

Gracey DR, Howard FM Jr, Divertie MB: Plasmapheresis in the treatment of ventilator-dependent myasthenia gravis patients. Report of four cases. Chest 85:739, 1984a.

Gracey DR, et al: Postoperative respiratory care after transsternal thymectomy in myasthenia gravis. A 3-year experience in 53 patients. Chest 86:67, 1984b.

Guthrie LG: Myasthenia gravis in the seventeenth century. Lancet 1:330, 1903.

Jaretzki A III: Thymectomy for myasthenia gravis: analysis of the controversies regarding technique and results. Neurology 48(suppl):52, 1997.

Jaretzki A III, et al: A rational approach to total thymectomy in the treatment of myasthenia gravis. Ann Thorac Surg 24:120, 1977.

Jaretzki A III, et al: Maximal thymectomy for myasthenia gravis. Results. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 95:747, 1988.

Jolly F: Ueber Myasthenia gravis pseudoparalytica. Berl Klin Wochenschr 32:1, 1895.

Keynes G: Discussion on myasthenia gravis and thymectomy. Proc R Soc Med 36:142, 1943.

Keynes G: Investigations into thymic disease and information. Br J Surg 62:449, 1955.

Kirschner PA: Myasthenia gravis. In Shields TW, LoCicero J III, Ponn RB (eds): General Thoracic Surgery. 5th Ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2000, p. 2207.

Kirschner PA, Osserman KE, Kark AE: Studies in myasthenia gravis: transcervical total thymectomy. JAMA 209:906, 1969.

Lewis JE, et al: Thymoma. A clinicopathologic review. Cancer 60:2727, 1987.

Oppenheim H: Weiterer Beitrag zur Lehre von den acuten Nichteitrigen eucephalitis und der Polioencephalomyelitis. Dtsch Z Nervenheild 15:1, 1899.

Oppenheim H: Die Myasthenische Paralyse Bulb rparalyse ohne anatomischen Befund). Berlin: S. Karger, 1901.

Savcenko M, et al: Video-assisted thymectomy for myasthenia gravis: an update of a single institution experience. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 22:978, 2002.

Schwab RS, Leland C: Sex and age in myasthenia gravis as critical factors in medicine and remission. JAMA 153:1270, 1953.

Seggia JC, Abreu P, Takatani M: Plasmapheresis as preparatory method for thymectomy in myasthenia gravis. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 53:411, 1995.

Wilks S: On cerebritis, hysteria and bulbar paralysis. Guy's Hospital Reports 22:7, 1877.

Yim PC, et al: Video-assisted thoracoscopic thymectomy for myasthenia gravis. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 11:65, 1999.

*Added by the Senior Editor.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 203