116 - Carcinoid Tumors

Editors: Shields, Thomas W.; LoCicero, Joseph; Ponn, Ronald B.; Rusch, Valerie W.

Title: General Thoracic Surgery, 6th Edition

Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

> Table of Contents > Volume II > The Esophagus > Section XXI - Operative Procedures in the Management of Esophageal Disease > Chapter 134 - Replacement of the Esophagus with Jejunum

Chapter 134

Replacement of the Esophagus with Jejunum

Henning A. Gaissert

Cameron D. Wright

Douglas J. Mathisen

Replacement of the esophagus remains a challenge for surgeons specializing in esophageal disease. The ideal conduit should restore normal swallowing, maintain active peristalsis, protect from acid reflux, be of sufficient length to replace as much of the esophagus as necessary, have a reliable arterial and venous supply, and not interfere with the function of the rest of the alimentary tract. No substitute satisfies all these criteria. None allows for normal swallowing. These principal observations are reason enough to preserve the esophagus whenever possible, particularly in benign disease.

Each of the available conduits (i.e., stomach, colon, and jejunum) has certain features that make it suitable for esophageal replacement. Certain circumstances may dictate the use of one conduit and exclude others. The surgeon treating esophageal disease must be familiar with all options. Successful replacement requires in-depth understanding of the technical aspects of each individual procedure. Proper patient selection and strict attention to preoperative and postoperative care ensures the greatest chance for a successful outcome and near-normal swallowing.

BACKGROUND

Techniques for intestinal interposition of the esophagus were developed at the beginning of the 20th century. Jejunum was first used as an antethoracic swallowing conduit in 1906 by Roux (1907), who performed a staged bypass of a caustic esophageal stricture with connection to the cervical esophagus 4 years later. In Moscow, Herzen (1908) successfully completed a similar two-stage procedure for a benign stricture of the esophagus in 1907. The jejunal segment was placed subcutaneously in both patients. Intrathoracic substernal and posterior mediastinal placements of the jejunum were accomplished successfully in 1942 and 1945 by Rienhoff (1946) of Baltimore. The British surgeon Brain (1967) used a short jejunal interposition between the distal esophagus and stomach for reflux-related strictures in 1951. Several years later, Merendino and Dillard (1955) demonstrated in animal experiments that an interposed jejunal segment prevented gastroesophageal reflux and peptic esophagitis after excision of the lower esophageal sphincter. Merendino and Thomas (1958) reported the first large series of jejunal interposition of the distal esophagus, which included 33 patients. Benign strictures and cardiospasm were the most common indications (82%). A single-stage procedure was used in all but 2 patients. Operative mortality was 12%. All patients had relief of dysphagia.

INDICATIONS

In adults, jejunal interposition is best suited for replacement of the distal esophagus. The indications for short-segment interposition of either jejunum or colon at Massachusetts General Hospital are listed in Table 134-1. Additional length may be obtained to reach the level of the aortic arch. Anastomosis to the lower cervical esophagus can rarely be achieved in adult patients. Therefore, indications for jejunal interposition of the esophagus are largely confined to disorders of the lower esophagus and esophagogastric junction. Exceptions to this rule are its use in children, reported by Ring and associates (1982), and when jejunal blood supply is supported by anastomosis to internal thoracic or cervical vessels, as recorded by Heitmiller and colleagues (2000).

Complications of gastroesophageal reflux disease constitute the most frequent indication for resection and intestinal interposition of the distal esophagus. Nondilatable strictures and severe, refractory esophagitis after failed antireflux procedures are the most common situations encountered. If esophagogastrostomy is performed after esophagectomy for complications of reflux disease, the incidence of severe gastroesophageal reflux, esophagitis, anastomotic stricture, and hemorrhage is high. Stomach with an intrathoracic anastomosis is therefore a less desirable conduit in this situation than either colon or jejunum.

Failed therapy or complications of motility disorders represent other important indications for intestinal interposition

P.2035

of the distal esophagus. Failed Heller myotomy for achalasia may lead to severe reflux and stricture not amenable to dilation and antireflux surgery. Colon and jejunum interposition is favored by Belsey (1965) and by Jamieson (1984) and Picchio (1997) and their associates to reduce postoperative gastroesophageal reflux. Sigmoid esophagus secondary to advanced achalasia may not respond well to myotomy and may require resection. This condition usually requires total esophagectomy, and the length of the conduit becomes an important consideration.

Table 134-1. Indications for Short-Segment Interposition at Massachusetts General Hospital | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Scleroderma often results in severe gastroesophageal reflux and stricture formation. Antireflux surgery is less likely to succeed, and when it fails or nondilatable strictures result, resection of the distal esophagus and colon or jejunal interposition are indicated, as suggested by Brain (1973) and Mansour and Malone (1988).

Caustic strictures tend to involve the entire length of the esophagus and rarely are isolated to the distal esophagus. For this reason, jejunum is used infrequently, but it may be suitable in children.

Nonvariceal acute hemorrhage of the esophagus usually can be controlled by nonsurgical methods. In those rare cases of uncontrollable hemorrhage from an ulcer, esophagitis, or Barrett's mucosa, resection may be the only option available for control. Because most cases are related to complications of reflux and occur in the setting of unprepared colon, jejunal interposition is probably the preferable way to reconstruct the esophagus. Its use avoids the potential for severe complications from gastroesophageal reflux after esophagogastrectomy. A jejunal segment can be constructed safely without bowel preparation, is resistant to acid reflux, and can be an effective antireflux operation.

Awareness of Barrett's esophagus and its relation to the risk of developing adenocarcinoma has increased, which has resulted in closer follow-up of patients with Barrett's esophagus and an increase in the number of patients found to have high-grade dysplasia, carcinoma in situ, or early invasive carcinomas. It is well recognized that Barrett's esophagus is an acquired phenomenon related to chronic gastroesophageal reflux. In patients with early, favorable malignant changes, jejunal interposition may be the method of choice to reconstruct the esophagus. This operation may avoid reflux and the risk of recurrence of the Barrett's mucosa after the more conventional esophagogastrostomy used for patients with cancer of the esophagus.

Esophageal perforation would be an unusual indication for jejunal interposition. Most perforations are associated with gross contamination of the pleural cavity and therefore are not suitable for an anastomosis in such a contaminated field. The condition of the patient often does not allow the extra time necessary for such a complex procedure as jejunal interposition. The primary goal in this situation is to deal with the perforation and save the patient's life. The only circumstance in which jejunal interposition may be appropriate is the patient with iatrogenic perforation of a nondilatable stricture diagnosed immediately after injury who is in good condition with minimal contamination and an irreparable stricture.

Contraindications to jejunal interposition include short bowel syndrome and Crohn's disease, while a short, fat jejunal mesentery limits cephalad reach. Anatomic variations may exist that would preclude the use of jejunum as well.

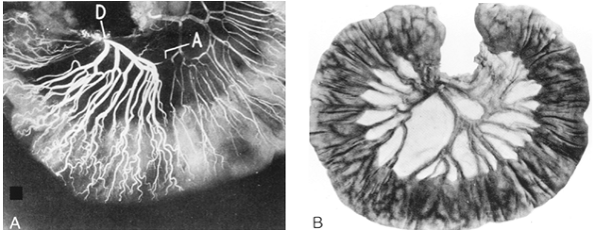

VASCULAR SUPPLY OF THE JEJUNUM

Despite the virtual absence of atherosclerotic disease, the jejunal vascular pedicle is less reliable than other conduits for two reasons, one anatomic and the other technical. In a study of anatomic variations in jejunal arterial arcades, Barlow (1955) found common abnormalities affecting collateral blood supply in 25% of specimens. Significant variations consisted of narrow vessels between adjacent jejunal arteries in 16%, and complete interruption between jejunal arcades in 6% of specimens (Fig. 134-1). Despite the frequency of this observation, however, clinical ischemic complications are rare, probably because arterial ischemia is recognized most often during preparation of the segment. The technical aspect of unreliability refers to the extent of dissection necessary to straighten the intestinal tube on its radially organized vascular supply. Stripping the peritoneal cover of mesenteric vessels in particular, veins risks injury and kinking of these vessels. Obstructed venous drainage is deleterious for graft survival and may, when not discovered during operation, lead to delayed graft necrosis. Meticulous attention to a straight course of the vascular pedicle avoids this pitfall.

PREOPERATIVE PREPARATION

Little preoperative preparation is required for jejunal interposition. In most patients, a suitable backup must be

P.2036

available if the use of jejunum is precluded. The usual alternative is colon, and therefore all patients should have a bowel preparation. Broad-spectrum antibiotics are given perioperatively.

|

Fig. 134-1. A. Angiogram of proximal mesenteric arcade. Injection of the duodenal end of the arcade (D) demonstrates narrowing in the arcade (A). B. Photograph of proximal jejunum with interrupted arcade and absence of communication between two adjacent branches of the superior mesenteric artery. From Barlow TE: Variations in the blood supply of the upper jejunum. Br J Surg 43:473, 1955. With permission. |

OPERATIVE TECHNIQUE

Posterior Mediastinal Position

Single-lung ventilation through a double-lumen tube allows for the best exposure for the operation. Esophagogastroscopy is performed to assess the pathology and its extent. The patient is placed in the left thoracotomy position, rotating the left hip backward for abdominal exposure. A left thoracoabdominal incision through the seventh or eighth intercostal space with peripheral diaphragmatic incision provides excellent exposure. The entire length of abnormal esophagus is mobilized. This step includes circumferential dissection of the gastroesophageal junction, which, after prior surgical procedures, may be involved in dense scarring.

The cardia is divided with a linear stapler, and the staple line is oversewn with interrupted sutures. A previous fundic wrap, if present, is usually included in the specimen. Short gastric vessels are divided to give access to the posterior gastric wall for anastomosis. The left gastric artery is preserved in the patient with benign disease.

Preparation of the Graft

Once the length of esophagus to be replaced is determined, an isoperistaltic graft of adequate length is prepared. Inspection of the mesentery demonstrates the jejunal arteries, vascular arcades, and vasa recta between the arcades and bowel wall. If these structures are obscured by fat, intraoperative transillumination is helpful. Observation of uninterrupted arcades without stenosis is essential to ensure satisfactory arterial supply throughout the graft. The first two or three jejunal arteries are usually short and unacceptable as a pedicle. Division of the first or second jejunal arteries may also compromise the blood supply of the fourth portion of the duodenum. Greater length of the jejunum is achieved by selecting a more distal vascular pedicle. Because of the radial blood supply, vessels further down add greater curvature to the jejunal segment. Once the vascular pedicle is identified and before the jejunum is divided, the segment is isolated by clamping collateral vessels with small bulldog clamps. A 10-minute test clamp time is sufficient to determine whether perfusion is adequate to ensure a viable jejunal segment.

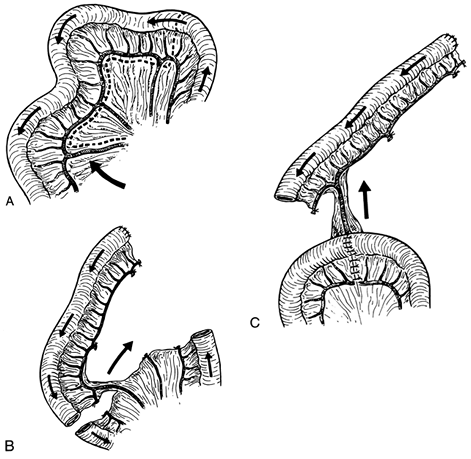

The collateral vessels are now divided. The jejunum is divided with linear staplers, and jejunal continuity is restored. The natural curve of the isolated loop may be straightened by incising the peritoneum toward the bowel wall. If secondary arcades of sufficient size are present closer to the bowel, the primary arcade may be divided to further straighten the graft (Fig. 134-2). These maneuvers must be performed with great care. The eventual placement of the pedicle is critical to ensure the absence of kinking, torsion, and tension. The jejunum is positioned in a retrocolic fashion through an opening created in the transverse mesocolon. The vascular pedicle and jejunal segment are brought posterior to the stomach and through the esophageal hiatus to lie in the posterior mediastinal bed of the esophagus. This positioning ensures a straight passage from esophagus through the graft to the stomach.

P.2037

Esophagojejunal Anastomosis

The esophagojejunal anastomosis is usually oriented end to side. No attempt should be made to straighten the jejunal segment to allow end-to-end anastomosis. Division of vessels near the end of the jejunum or kinking from excessive tension jeopardizes the blood supply and risks ischemic necrosis. The proximal stapled end of the jejunum is turned in with interrupted sutures. The anastomosis is constructed no more than 2 cm from the end of the jejunum. It is important to perform the anastomosis no further distally than this point to avoid creating a long afferent limb that may lead to problems with stasis and regurgitation. The anastomosis should appose the seromuscular jejunum and muscular layers of the esophagus. The inner layer consists of full-thickness jejunum and esophageal mucosa.

|

Fig. 134-2. Preparation of the jejunal segment. A. An appropriately long pair of mesenteric vessels is selected (arrow), and the mesentery proximal to these vessels and central to the marginal arcade is incised. B. After clamp occlusion, the marginal arcade and remaining mesenteric branches are divided and ligated. The jejunum is divided and the proximal end of the segment is oversewn. C. End-to-end jejunojejunostomy is performed and the mesenteric defect is closed. The vascular pedicle is isolated and oriented vertically. From Wright C, Cuschieri A: Jejunal interposition for benign esophageal disease. Technical considerations and long-term results. Ann Surg 205:54, 1987. With permission. |

Jejunogastric Anastomosis

In a posterior mediastinal position, the graft runs a straight course to the posterior gastric wall, and an anastomosis here is preferred to a meandering course toward the anterior aspect of the stomach. A button of gastric wall is excised from the fundus close to the greater curvature at least 2 cm away from the gastric staple line. The jejunogastric anastomosis is fashioned to this opening. The hiatus is tacked to the interposition to prevent herniation of abdominal contents and compression of the vascular pedicle. Exposure of several inches of graft to intraabdominal pressure may decrease gastric reflux into the jejunum or esophagus. Excessive length of the distal end of the jejunal segment is removed by dividing the mesentery immediately adjacent to the jejunum, preserving the vascular pedicle and arcade

P.2038

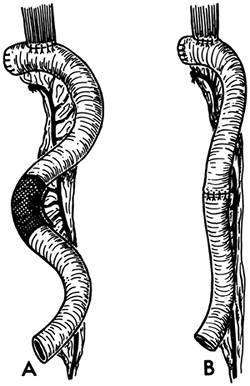

to the remainder of the jejunum. To adjust the length of an already completed interposition, one of us (CW) and Cuschieri (1987) suggest a box resection, removing a short length of jejunum in the middle aspect of the segment and dividing the mesentery close to the bowel wall (Fig. 134-3).

Pyloric Drainage

Ellis and associates (1988) reported that the incidence of postoperative gastric outlet obstruction is approximately 9% to 10% when no drainage procedure is added. Therefore, it is best to perform pyloroplasty or pyloromyotomy and cover the suture line with omentum. A nasogastric tube is advanced through the jejunal segment during completion of the anastomosis. Temporary gastrostomy and jejunostomy tubes may be used.

|

Fig. 134-3. A. Technique of resection of redundant jejunum is strictly limited to the bowel wall (shaded area). The terminal vessels are ligated close to the jejunal wall to avoid damage to the vascular pedicle. B. After excision of the segment, continuity is restored by a single-layer anastomosis. With experience and careful construction of the vascular pedicle, the need for resection of segments of the interposed jejunum to overcome redundant looping does not arise often. From Wright C, Cuschieri A: Jejunal interposition for benign esophageal disease. Technical considerations and long-term results. Ann Surg 205:54, 1987. With permission. |

Antethoracic and Substernal Position

Foker and associates (1982) have used their technique for long-segment jejunal interposition in two or three stages in children and in a small number of adults. In children, the first stage is carried out anywhere from 6 months to 11 years of age, with the second stage days to months later. The interposition can be mobilized and placed behind the sternum at a later date. The first stage consists of a Roux-en-Y jejunal interposition with a cervical jejunostomy. The authors emphasize regular division of secondary arcades to gain additional length, but graft preparation is otherwise similar to the aforementioned technique.

Foker and associates generate a generous subcutaneous tunnel with its lateral dimensions extending beyond the nipple line to prevent graft compression and venous outflow obstruction. The xiphoid is resected, and the round hepatic ligament is divided and suspended for the same purpose. The graft is then passed in a retrocolic manner and into the neck, where a cutaneous esophagostomy is performed. During the second stage, the cervical anastomosis and jejunoantrostomy are created using a single-layer technique with 6-0 Prolene. The interposition also may be transposed behind the sternum at this time.

POSTOPERATIVE CARE

The patient is extubated when awake and once cough is effective, usually on the first postoperative day. Epidural anesthesia or patient-controlled analgesia is used for pain control. Until sputum is raised effectively, regular chest physical therapy is continued. A meglumine diatrizoate (Gastrografin) swallow is obtained when bowel activity resumes and flatus is passed. If no leak is apparent and anastomoses are patent, the nasogastric tube is removed and oral intake is advanced gradually.

POSTOPERATIVE COMPLICATIONS

Major complications of jejunal interposition at the Massachusetts General Hospital are listed in Table 134-2.

Pulmonary Complications

Atelectasis and pneumonia are the most frequent complications unrelated to technique and occur in approximately one-third of all patients. This high incidence is sufficient reason to insist that all patients cease smoking more than 2 weeks preoperatively. Flexible fiberoptic bronchoscopy

P.2039

and minitracheostomy have been particularly helpful in the treatment of postoperative sputum retention. Adequate pain control is imperative to allow good pulmonary toilet and is greatly facilitated by anesthetic techniques such as epidural analgesia and patient-controlled analgesia.

Table 134-2. Complications of Short-Segment Interposition at Massachusetts General Hospital | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||

Graft Necrosis

Graft necrosis can be related to either arterial or venous insufficiency. Arterial ischemia is usually immediately apparent in the operating room, whereas the development of venous congestion and infarction is more insidious. The complication is often recognized late and therefore is associated with a high mortality. Sudden worsening in a patient's condition with unexplained tachycardia, fever, sepsis, profuse watery chest tube drainage, or fetor should be investigated aggressively. A high index of suspicion and early reexploration with removal of the entire graft provides the only opportunity to save the patient. In Brain's (1967) series of 36 jejunal transplants, four patients sustained venous infarction, of whom two died. The decision whether to immediately restore esophagointestinal continuity depends on the patient's condition, the presence of local sepsis, and the availability of alternative conduits. If in doubt, delayed reconstruction is the safer alternative.

Graft Perforation

Polk (1980) reported perforation of the jejunal graft resulting from unintentional manipulation of the nasogastric tube occurring in two patients and leading to one patient's death. Treatment in the surviving patient consisted of local repair of the perforation.

Anastomotic Leak

The esophagojejunal anastomosis may be the most exposed to leakage. The mortality of a free intrathoracic leak accompanied by sepsis remains high; however, leaks that are contained and not associated with signs of sepsis may heal with conservative management. Anastomotic leaks developed in 10% of the patients reported by one of us (CW) and Cuschieri (1987) and were associated with sepsis and death in one patient and noted as a radiologic finding only in two others. Management of a leak associated with sepsis consists of immediate reexploration, revision of the anastomosis, and coverage with a pedicled intercostal flap or omentum and adequate drainage. Small, asymptomatic leaks usually close after antibiotic therapy and delayed feeding with appropriate chest drainage.

Stricture

Dave and associates (1972) noted a proximal anastomotic stricture in 5 of their 81 patients with Roux-en-Y or interposition esophagojejunostomy for benign esophageal disease. Strictures should be uncommon. Technical problems, rough handling of the mucosa, tension, ischemia, and gastroesophageal reflux are the most prominent etiologic factors. Initial treatment of a benign stricture is dilation. A sufficient period of time from surgery should pass to allow adequate healing before attempting dilation (3 to 4 weeks). Maloney or Savary dilators or balloon dilation are all useful in selected patients. When dilation fails to give prolonged relief from dysphagia, the anastomosis should be revised, either by resection and reanastomosis or with a Heineke-Mikulicz-type stricturoplasty.

Graft Redundancy

The fanlike configuration of the jejunal mesentery provides for a relatively short pedicle and a long intestinal tube. Jejunal redundancy is likely present from the time of the initial operation, but it may progress postoperatively. Failure to straighten the jejunal segment adequately results in a meandering interposition prone to twisting and kinking of the intrathoracic portion, causing a delay of swallowing or obstruction. This problem is best prevented by avoiding excessive graft length at the time of surgery.

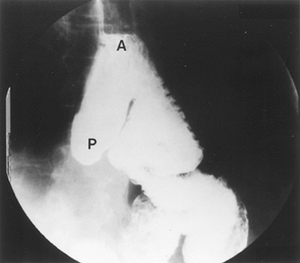

Afferent Jejunal Pouch

Creating the end-to-side anastomosis too far from the divided end of the jejunum may predispose to late development of an afferent limb and the formation of a pouch (Fig. 134-4). The pouch acts as an intermediate reservoir for food, causing pain from distention, poor transit of food, regurgitation of undigested food, and foul breath. If symptoms are severe and persistent, resection of the afferent limb or anastomosis between afferent and efferent limb is required.

POSTOPERATIVE MORTALITY

Operative mortality after jejunal interposition is related to whether the procedure is used as the primary surgical intervention

P.2040

or after multiple previous operations. In the latter setting, 2 (10.5%) of 19 patients died at Massachusetts General Hospital, as reported by one of us (HAG) and co-workers (1993). Brain (1967) reported a mortality of 11%. In the study by Dave and associates (1972) of 81 patients undergoing esophagojejunostomy for benign disease during a 26-year period, 18 patients had interposition of an isolated loop. Overall mortality was 9.9%. One of us (CW) and Cuschieri (1987) reported one death related to sepsis after emergency interposition (3.3%), and Polk (1980) reported one death from iatrogenic graft perforation (4.0%). Ring and associates (1982) had no mortality in 32 children undergoing staged jejunal interposition.

|

Fig. 134-4. Jejunal interposition with preferential flow of contrast into the pouch. A, proximal anastomosis; P, afferent pouch. From Gaissert HA, Mathisen DJ: Short segment colon and jejunal interposition. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 4:328, 1992. With permission. |

LONG-TERM FUNCTIONAL RESULTS

Few objective parameters exist for long-term success other than weight gain, the ability to eat an unrestricted diet, and freedom from symptomatic reflux. Patient satisfaction ranks highest in importance. Late results of jejunal interposition compare favorably with short-segment colon interposition in most series.

Brain (1967) monitored 29 patients for a mean period of 5 years after jejunal interposition. All were described to swallow without difficulty, although three cases were considered failures because of diet restrictions in one patient with scleroderma and failure to gain weight and heartburn in two others. On radiographic studies, 72% of the patients had reflux into the graft, reaching the esophagus in 40%. No patient was demonstrated to have reflux esophagitis. Long-term follow-up of 19 patients by one of us (CW) and one of us (HAG) (1987) revealed that 2 had mild dysphagia to solids, 1 had frequent regurgitation, and 2 had severe eructation of foul air. All but one of these patients gained weight postoperatively.

Of 16 patients (84%) followed late after jejunal interposition at Massachusetts General Hospital and recorded by Gaissert and colleagues (1993), 7 had excellent results, with minimal or absent symptoms; 6 had good results, with complaints of slowed swallowing or occasional regurgitation; and 3 had a fair result, with dysphagia to some solids, frequent regurgitation, or intermittent dilatation.

The contribution of peristalsis to emptying of the conduit is controversial. Jones and co-workers (1971) observed effective intestinal graft contractility measured by acid clearance and cinefluoroscopy in colon interposition. More sophisticated evaluation by Clark and associates (1976) involving fluoroscopy and manometry, however, identified upper esophageal contractions and gravity as the major propulsive forces in deglutition and failed to demonstrate active contribution of colonic peristalsis. The active propulsion of swallowed food in jejunal grafts, observed by Roux in his first successful subcutaneous graft, is believed to result in superior long-term function. More rapid emptying was seen by Hanna and associates (1967) and Ferrer and Bruck (1969) during deglutition in the jejunal group than in the colon and stomach groups. One of us (HAG) and co-workers (1993) reported that food provocation studies do not demonstrate peristalsis.

Results of cinefluoroscopy should be interpreted with caution, because mere contraction does not in itself represent propulsion of swallowed food. One of us (CW) and Cuschieri (1987) found that mean esophageal transit time in jejunal grafts as measured during swallow of a radiolabeled standard solid, as suggested by Cranford and associates (1987), is relatively long (3.6 minutes compared with 10.4 seconds in healthy volunteers). On the basis of 1-second frame analysis, jejunal contractions were found to be segmental rather than peristaltic. Because the passage of food is rapid through the remaining cervical esophagus and is relatively delayed by the slower small bowel contractions, an intermediate food reservoir may form at the esophagojejunal anastomosis. This development may explain the slowing of swallowing noted by some patients with jejunal grafts.

COMMENT

No known esophageal substitute restores swallowing to a normal physiologic state. This fact underscores the need to apply the initial surgical treatment of benign esophageal disease with restraint and great care to avoid the need for intestinal interposition. Both jejunum and colon interposition have good long-term results with satisfactory palliation

P.2041

of swallowing, an unrestricted diet in most patients, and adequate control of reflux or dysphagia. Patient satisfaction is the paramount standard for grading the success of esophageal substitution.

REFERENCES

Barlow TE: Variations in the blood supply of the upper jejunum. Br J Surg 43:473, 1955 1956.

Belsey R: Reconstruction of the esophagus with left colon. J Thorac Surg 49:33, 1965.

Brain RHF: The place for jejunal transplantation in the treatment of simple strictures of the oesophagus. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 40:100, 1967.

Brain RHF: Surgical management of hiatal hernia and oesophageal strictures in systemic sclerosis. Thorax 28:515, 1973.

Clark J, et al: Functional evaluation of the interposed colon as an esophageal substitute. Ann Surg 183:93, 1976.

Cranford CA Jr, et al: New physiological method of evaluating oesophageal transit. Br J Surg 74:411, 1987.

Dave KS, et al: Esophageal replacement with jejunum for non-malignant lesions: 26 years' experience. Surgery 72:466, 1972.

Ellis FH Jr, Gibb SP, Watkins E Jr: Limited esophagogastrectomy for carcinoma of the cardia. Indications, technique, and results. Ann Surg 208:354, 1988.

Ferrer JM Jr, Bruck HM: Jejunal and colonic interposition for non-malignant disease of the esophagus. Ann Surg 169:533, 1969.

Foker JE, Ring WS, Varco RL: Technique of jejunal interposition for esophageal replacement. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 83:928, 1982.

Gaissert HA, et al: Short-segment intestinal interposition of the distal esophagus. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 106:860, 1993.

Hanna EA, Harrison AW, Derrick JR: Long-term results of visceral esophageal substitutes. Ann Thorac Surg 3:111, 1967.

Heitmiller RF, et al: Long-segment substernal jejunal esophageal replacement with internal mammary vascular augmentation. Dis Esophagus 13:240, 2000.

Herzen P: A modification of the Roux esophagojejunogastrostomy (Eine Modifikation der Roux'schen Oesophagojejunogastrostomie). Zentralbl Chir 35:219, 1908.

Jamieson WRE, et al: Surgical management of primary motor disorders of the esophagus. Am J Surg 148:36, 1984.

Jones EL, et al: Functional evaluation of esophageal reconstructions. Ann Thorac Surg 12:331, 1971.

Mansour KA, Malone CE: Surgery for scleroderma of the esophagus. A 12-year experience. Ann Thorac Surg 46:513, 1988.

Merendino KA, Dillard DH: The concept of sphincter substitution by an interposed jejunal segment for anatomic and physiologic abnormalities at the esophagogastric junction with special reference to reflux esophagitis, cardiospasm, and esophageal varices. Ann Surg 142:486, 1955.

Merendino KA, Thomas GI: The jejunal interposition operation for substitution of the esophagogastric sphincter: present status. Surgery 4:1112, 1958.

Picchio M, et al: Jejunal interposition for peptic stenosis of the esophagus following esophagomyotomy for achalasia. Int Surg 82:198, 1997.

Polk HC Jr: Jejunal interposition for reflux esophagitis and esophageal stricture unresponsive to valvuloplasty. World J Surg 4:731, 1980.

Rienhoff WF: Intrathoracic esophagojejunostomy for lesions of the upper third of the esophagus. South Med J 39:928, 1946.

Ring WS, et al: Esophageal replacement with jejunum in children. An 18 to 33 year follow-up. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 83:918, 1982.

Roux C: L'oesophago-jejuno-gastrome: nouvelle operation pour retrecissement infranchissable de l'oesophage. Semaine Medica (Paris) 27: 37, 1907.

Wright C, Cuschieri A: Jejunal interposition for benign esophageal disease. Technical considerations and long-term results. Ann Surg 205:54, 1987.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 203