28 - Understanding and Assessing Pain and Pain Syndromes

Editors: Shader, Richard I.

Title: Manual of Psychiatric Therapeutics, 3rd Edition

Copyright 2003 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

> Table of Contents > 28 - Understanding and Assessing Pain and Pain Syndromes

function show_scrollbar() {}

28

Understanding and Assessing Pain and Pain Syndromes

Wayne A. Ury

Richard I. Shader

Pain is one of the most common symptoms from which patients suffer and for which relief is sought. Unfortunately, surveys of patients seen in primary care practices suggest that pain is underrecognized and often is inadequately treated. Most pain syndromes (i.e., possibly as high as 90%) can be diagnosed on the basis of a history and physical examination alone, and, with standard therapies, most acute and chronic cancer pain can be meaningfully alleviated; estimates suggest relief is possible for greater than 90% of patients with cancer-related pain. Although chronic pain remains a more elusive entity, recent improvements in pain management have made these syndromes more treatable and have reduced the likelihood of unwanted consequences from treatment.

Uncontrolled pain is a major public health problem that is only now beginning to be addressed formally by the medical community. It precludes a satisfactory quality of life by markedly interfering with the individual's activities of daily living and social interaction and by its impact on mood and psychologic functioning (e.g., increased risk of anxiety, depression, suicidal ideation). Back pain is the second leading cause of lost work days in the United States, with a cost to the economy and to workers suffering from this chronic medical problem. Seventy-five percent of patients with cancer and 50% of patients with human immunodeficiency virus suffer from moderate to severe, daily, chronic pain for a significant period of their illness. This has tremendous psychologic, social, and financial implications for the patient and his or her family. Pain is even prevalent among well-functioning ambulatory patients; it compromises function in about one-half of the patients who experience it.

Adequate assessment is the crucial first step in defining a treatment strategy for the patient with pain. The major goal of an assessment strategy is to use the most appropriate diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to define the cause of the pain and to direct its treatment. Advances in the understanding of the pathophysiology of pain, coupled with the availability of validated pain measurement tools, facilitate such an assessment. Identification and categorization of a wide range of distinct yet characteristic pain syndromes provide the clinical basis for choosing specific therapeutic strategies.

Advances in knowledge about pain need more integration into daily clinical practice. More importantly, pain should be viewed as a common symptom that can be detected by screening high-risk populations, such as cancer, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), and diabetic patients. Because many illnesses are accompanied by at least some amount of pain, clinicians should also consider pain detection and relief as an integral part of every patient's treatment plan. In general, pain should be managed in parallel and in concert with treatments aimed at disease eradication or containment.

I. Epidemiology

Pain is a major part of most acute and chronic illnesses. For example, approximately 50% of AIDS patients suffer from daily pain that is moderate to severe in nature. Almost 30% of adult diabetic patients suffer from pain due to diabetic neuropathy, foot ulcers, or recurrent cellulitis. Regrettably, recent research has found that approximately 40% of conscious patients are in moderate to severe pain during the last 10 days of life and that greater than 60% of postoperative patients are in moderate to severe pain during the first 72 hours after surgery.

Currently, the most informative epidemiology of pain syndromes is found in the oncology literature. It illustrates how pain is an underrecognized and poorly treated component of medical illness, even though pain is commonly known to be of high prevalence and to be a cause of great suffering. Prevalence data indicate that, currently, about 17 million people are living with cancer worldwide.

P.421

Numerous studies have demonstrated that the prevalence of pain increases with the progression of disease and that the intensity, type, and location of pain varies according to the primary site of cancer, the extent of disease, the rate of progression, and the treatments used. In one American survey of 1,308 oncology outpatients, 67% reported recent pain and 36% reported pain severe enough to impair function. Another study reported pain in 63% of 246 randomly selected inpatients and outpatients undergoing active treatment for prostate, colon, breast, or ovarian cancers; pain intensity was rated moderate to severe by 43% of respondents. Surveys of patients admitted to palliative care or hospice services suggest that pain is inadequately relieved in one-half to 80% of patients at the time of intake. In a French survey, 69% of the cancer patients rated their worst pain to be at a level that impaired their ability to function. Although these reports highlight cancer pain as a major problem affecting quality of life, pain is still poorly addressed by most clinicians.

II. Definitions and Categories of the Types of Pain

The International Association for the Study of Pain defines pain as an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage or described in terms of such damage. Pain is always subjective; each patient's description of pain will be different. Moreover, no definitive way exists for distinguishing pain occurring in the absence of tissue damage from pain resulting from damaged tissue.

However, simple and practical tools (e.g., visual analog scales) provide a means by which the severity of pain can be serially assessed. The combination of objective and subjective data can be used by the clinician to make a presumptive diagnosis, to develop an initial treatment plan, and to assess the response to treatment. Evaluating and treating pain is a clinical skill that requires both clinical acumen and up-to-date factual knowledge. Most importantly, it relies on a trusting ongoing relationship between the patient and care provider.

The general focus of diagnosis should be to understand the pathophysiologic process that underlies the pain, to assess the quality of the pain (e.g., description, temporal nature), and to gauge the severity of the pain. Although assessing the underlying cause of the pain may be impossible and even though, in some cases, the etiology of the pain does not determine the treatment approach, more often than not, without an adequate investigation and understanding of the underlying pathophysiologic process, pain relief may be inadequate and unsustainable. A review of 100 consecutive cancer patients with pain found that 61% had undiagnosed etiologies that had important treatment implications. Therefore, providing morphine to a patient with severe pain before a thorough workup makes the achievement of long-term relief less likely.

A. Types of Pain

Numerous ways of categorizing the different types of pain exist. These categories have practical value because they capture the multidimensional aspects of pain. They also can be confusing because they overlap with each other, and their descriptors can have different meaning and treatment implications in different patients. In general, pain can be classified based on its temporal nature (acute vs. chronic), intensity (mild, moderate, or severe), or physiologic basis (inflammatory, neuropathic, traumatic, postsurgical, cancer pain). However, the patients' subjective descriptions of the pain and how it affects their emotional, social, physical, and occupational functioning can often be the most important factor in understanding it and in determining a treatment plan.

B. Temporal Pattern

Pain may be defined on a temporal basis. That cancer patients have both acute and chronic pain is well recognized. Most surgical pain is of an acute (and severe) nature. Most arthritic pain is chronic, although it may be severe.

Acute pain. Acute pain is characterized by a well-defined temporal pattern of pain onset that is generally associated with subjective and objective physical signs and hyperactivity of the autonomic nervous system. Acute pain is usually self-limited, and it responds to analgesic drug therapy

P.422

and treatment of its precipitating cause. For acute muscle pain, applications of heat or cold may be beneficial. Acute pain can be further subdivided into subacute and intermittent or episodic types. Subacute pain describes pain that comes on over several days, often with increasing intensity, and it represents a pattern of progressive pain symptomatology. Episodic pain refers to pain that occurs during confined periods of time on a regular or irregular basis.Chronic pain. Chronic pain is defined as pain that persists for more than 2 months, often with a less well-defined temporal onset. Adaptation of the autonomic nervous system occurs, and patients with chronic pain usually lack the objective signs common to the patient with acute pain. Chronic pain is associated with significant changes in personality, life-style, and functional ability. Such patients require a management approach that encompasses not only the treatment of the cause of pain but also attention to the complications that may have ensued in their functional status, social lives, and personalities as a result.

Breakthrough and baseline pain. Baseline pain is defined as that pain reported by patients as the average pain intensity experienced for 12 hours or more during a 24-hour period. Breakthrough pain is characterized by a transient increase in pain to greater than moderate intensity that occurs on a baseline pain of moderate intensity or less. In a study of 70 adult cancer inpatients, 65% reported breakthrough pain. Most breakthrough pain is usually thought to be associated with a known malignant cause; in one study, however, only one-fifth of these reports was associated temporally with tumor therapy and 4% were unrelated to either the cancer or its treatment.

C. Intensity of Pain

Pain may also be defined on the basis of intensity, and an extensive literature on the use of words to describe pain intensity is found. However, limitations to a unidimensional concept of pain described solely in terms of pain intensity is recognized. Specific categorical scales of pain intensity, in which patients are asked to describe their pain as mild, moderate, severe, or excruciating, have been used.

Visual analog scales have also been used. Numerical scales that ask patients to rate their pain as a number between 1 ( no pain ) and 10 ( worst possible pain ) are often commonly used. These different scales to capture a patient's experience of pain have their limitations, but they are part of a series of validated instruments that include a measure of pain intensity as one of the components of the pain experience to be defined. In one French study of 605 patients across all institutions (cancer centers, university hospitals, state hospitals, private clinics, and one home care setting), patients consistently rated their pain as being more severe than their doctors did, indicating that French physicians underestimate the severity of their patients' cancer pain.

D. Neurophysiologic Classification of Pain

Neurophysiologic classifications of different forms of pain can be helpful in understanding the physiologic or neuroanatomic basis of pain and can therefore help in defining a well-targeted treatment plan. Unfortunately, these classifications can also be confusing, and they can actually result in a failure to consider the other aspects of pain assessment, such as pain severity. Therefore, although considering the pathophysiology of a patient's pain is always important, the temporal nature, the severity, and the patient's subjective description need to also be factored into the assessment.

Pain can be caused by injury to a tissue, a peripheral nerve or nerve root, or the central nervous system. The two major modulators of pain are inflammation and neuronal activity. Therefore, the presence (or absence) of inflammation and neuronal damage or activity need to be considered in every patient's assessment. Inflammation can occur as a result of trauma, surgery, autoimmune and rheumatologic disorders, space-occupying lesions, infection, and tissue damage or destruction (by tumors). Examples of neuronal activity

P.423

and damage that can cause pain include neuropathies, thalamic stroke or injuries causing afferent neuronal activity, radiculopathies and root compression, and nerve roots that were cut during a surgical procedure.

Inflammation-mediated pain. When injury to a tissue or organ happens, an inflammatory response occurs to protect and to repair the injured site(s). This response is what causes the sensation of pain. Prostaglandins, interleukins, tissue necrosis factors, and other molecules are the modulators that are the chemical basis of this type of pain. Inflammatory pain is generally described as throbbing, pressure-like, and achy.

Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and, to some degree, acetaminophen reduce these effects by inhibiting the release and activity of prostaglandins and other modulators. Therefore, in general, whenever evidence for tissue injury is found, these agents should be considered. When inflammatory pain becomes moderate or severe, short-acting opioids may be needed to decrease the perception of pain by affecting the neurons by which the pain sensation is transmitted from the peripheral tissue to the brain.

Neuropathic pain. This type of pain results from damage to a nerve root or peripheral nerve. It is commonly seen in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (human immunodeficiency virus neuropathy and iatrogenic neuropathies secondary to protease inhibitors), diabetes mellitus (diabetic neuropathy), and obesity (sciatica). It is described as a burning or electrical sensation, and it can coexist with a loss of sensation. Although the basis of this type of pain is poorly understood, tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) (e.g., amitriptyline) and certain anticonvulsants (e.g., carbamazepine, gabapentin, valproic acid) are effective.

III. Principles of Clinical Assessment

As noted, most pain can be diagnosed by history and physical examination alone. However, if a diagnosis remains unclear, a pain relief workup to diagnose the etiology of the problem should be initiated immediately in parallel to the initiation of pain treatment. Certain general principles should be considered when evaluating all patients who complain of pain (Table 28.1). Lack of attention to these general principles is a major cause for misdiagnosis of the specific pain syndrome.

TABLE 28.1. PRINCIPLES OF Pain ASSESSMENT | |

|---|---|

|

P.424

The most important guiding principle in pain assessment (and treatment) is to always believe the patient. Clinicians have been shown to have a tendency to minimize or dispute a patient's rating of pain severity. This can result in inadequate assessment and treatment.

That the clinician and patient design a diagnostic and therapeutic approach that suits the individual needs and style of each patient is also of great importance. The evaluation of the patient must also be closely allied to the patient's level of function, ability to participate in a diagnostic workup, and willingness to undergo the necessary diagnostic approaches; to objective evidence that treatment approaches may be beneficial; and to life expectancy. Careful judgment should be used in choosing the diagnostic approaches. Only those tests that will have a direct impact on the choice of the therapeutic strategy should be employed. The random use of diagnostic procedures in this group of patients is inappropriate, and it may have an adverse effect on the quality of life for such patients. Open discussion with the patient about the need for assessment and the therapeutic options is critical as this will provide the necessary dialogue that will allow the patient to be part of the decision-making process. In some patients, diagnostic procedures, such as myelography or magnetic resonance imaging, are inappropriate because they simply confirm the existence of disease for which no safe treatments are available.

A. Role of the Patient's History in the Assessment of Pain

Critical to the management of the patient with pain is the establishment of a trusting relationship with the physician. The complaint of pain is a symptom, not a diagnosis. Remembering that the diagnosis of the specific pain syndrome and a complete understanding of the psychologic state of the patient is not always made on the initial evaluation is important. In fact, several weeks may be required to define its nature because of the lack of radiologic or pathologic verification. Numerous examples point out the limitations of diagnostic procedures in providing proof of the validity of patients' complaints.

A comprehensive evaluation involves taking a careful history; performing a detailed medical, neurologic, and psychologic evaluation; developing a series of diagnosis-related hypotheses; and ordering the appropriate diagnostic studies. The history should include the patient's description of (a) the site of the pain, (b) the quality of the pain, (c) any exacerbating and relieving factors, (d) its temporal pattern, (e) its exact onset, (f) the associated symptoms and signs, (g) its interference with activities of daily living, (h) its impact on the patient's emotional state, and (i) any response(s) to previous and current analgesic therapies. Multiple pain complaints are common in patients with advanced disease. Prioritizing them before pain treatment is initiated is usually helpful.

B. Evaluation of the Emotional State of the Patient

Psychologic factors have been shown to play a significant role in accounting for the differences in pain experiences in patients with cancer and other serious illnesses. Therefore, classifying the patient's current level of anxiety and depression and learning whether episodes were experienced before pain onset are imperative. Information on how the patient handled previous episodes of pain may provide insight into whether a pattern of chronic illness behavior is present. Because patients have their own unique understanding of the meaning of pain to them, having each patient elaborate this meaning is useful. Always keeping in mind the idea that complaints of physical pain can often be a way of expressing emotional pain or conflict is important.

C. Relationship Between Anxiety and Depressive Disorders and Pain Complaints

Depression, anxiety, social isolation, and poor adherence to other prescribed therapies have all been shown to result from undiagnosed, untreated, or inadequately treated pain. Depression disorders occur in as many as 25% of cancer patients. Although the development of depression in cancer patients has been shown to be independent of the degree and/or severity

P.425

of pain, other studies in cancer and noncancer populations have shown that depressed patients have a greater perception of pain, that they are more severely affected, and that they are less responsive to pain treatment. Treatment of depression (see Chapter 18) or anxiety (see Chapter 14) has been shown to reduce patients' perceptions of their pain and to improve their responsiveness to pain treatment.

Unrelieved or escalating pain can be a reason for suicide (see Chapter 17) and for requests for physician-assisted suicide in patients with debilitating chronic or terminal illness. Therefore, special attention should be given to complete pain relief and regular reassessment. The physician needs to be available and to respond rapidly to worsening pain. To assess patients' capabilities of asking for help when their pain worsens, asking them to define what they would do if the pain were to become intractable or intolerable and if they ever have suicidal thoughts or a pact with a family member is helpful.

D. Addictive Disorders and Pain

The potential for alcohol and drug abuse, especially in those patients with a previous history of addiction, to occur as a result of treatment is a common concern among clinicians. However, good evidence exists that shows that this concern is probably only warranted in those patients with a past or current history of drug or alcohol addiction.

Surveys of cancer patients show that most are fearful of becoming addicted and that they would actually prefer not to use opioids for pain relief. Studies of patient-controlled anesthesia have shown that, with the exception of patients with addiction, patients will tend to underuse their pain medication unless they are strongly encouraged by staff to use it. Even though a limited population for whom patient-controlled anesthesia opioid use may be problematic does exist, those jurisdictions (usually states) that permit it have special regulations to govern its use. Clinicians need to understand and to follow any regulations and policies governing the prescription of opioids and other pain remedies in their practice locale.

Patients with a history of addiction have an ethical right to pain relief and the same treatment options as nonaddicted patients. Unfortunately, as a result of the prevailing negative attitudes about drug addiction, patients with a history of premorbid addiction are at high risk for poor assessment and treatment of their pain. Their complaints are often ignored or discounted, and treatments that are necessary for relief, such as opioids, are avoided. In addition to being aware of this tendency among clinicians, the clinician must also realize that, if a patient with a history of addiction does not get adequate pain relief, he or she may turn to illicit drugs or alcohol. In patients who have a history of addiction or in situations where the clinician has a strong suspicion of active illicit drug use, a clinician (usually a psychiatrist) with expertise in addiction should be consulted. Making these patients aware of these concerns and perhaps requiring participation in a drug treatment program as a prerequisite for treatment with opioids is also important.

E. Stress-Aggravated Pain Syndromes

Several pain syndromes do exist in which depression, anxiety, and stress (see Chapters 14 and 18) clearly play a causal role in the development of symptoms and their severity. These include disorders or syndromes, such as fibromyalgia, irritable bowel disorder, and atypical chest pain. In addition, keeping in mind that chest pain, chronic abdominal pain, and headaches are classic ways in which depression and anxiety present themselves in the primary care setting is important. In fact, approximately 20% of patients with major depressive episodes have been shown to have chronic complaints of headaches. In those patients in whom pain is integral to their generalized anxiety disorder or major depressive episode, treatment of the primary psychiatric illness will usually result in a resolution of the pain complaints.

Although the pathophysiologic basis of these syndromes remains unclear, treatment of any underlying depression and anxiety with antidepressants or cognitive-behavior psychotherapy has been shown to be of benefit. TCAs,

P.426

at dosages used to treat major depressive disorder, have been shown to be effective in decreasing the number and severity of pain complaints, in improving functional status, and in improving sleep. Although benzodiazepines can be of short-term benefit in relieving anxiety, increasing a patient's pain perception threshold, and decreasing back and muscle tension, they should be used for brief periods of time, preferably in conjunction with antidepressant treatment or psychotherapy.

F. Psychosomatic Pain Syndromes

In addition, some patients suffer from somatoform illnesses in which pain is either the primary or major complaint. These include somatoform disorder, which was formerly called psychogenic pain syndrome, hypochondriasis, and conversion disorders. Although an in-depth discussion of these syndromes is beyond the scope of this chapter, one guiding principle is clear these generally are diagnoses of exclusion. Before they can be invoked as the cause of pain, the possibility of a medical or neurologic etiology, an addictive disorder, an affective disorder, or an anxiety disorder needs to be ruled out. Because differentiating these is quite complex, a psychiatrist with expertise in consultation liaison psychiatry should be consulted.

Interestingly, some data suggest that greater than 90% of patients with four or more pain complaints per visit with their primary care physician for which no medical or neurologic etiology can be found meet criteria for major depressive disorder or dysthymic disorder. Another finding is that, in greater than 90% of these patients, most or all of the pain complaints resolved with TCA treatment. Therefore, an empirical trial of a TCA, the class of antidepressants with the most support in the literature, or of another type of antidepressant at the standard dosages used to treat major depressive disorder should be considered.

G. Physical and Neurologic Examinations

These examinations usually provide the data necessary to corroborate the history. A thorough examination also allows the clinician to inspect the patient visually, to palpate the site of pain, and to look for the associated physical and neurologic signs that might help to define the nature of the pain complaint. A more definitive treatment approach can then be initiated.

Realizing that, even in some patients with severe pain, minimal or no physical or neurologic findings may be found during the initial examination is important. In these instances, treatment that provides pain relief should be instituted immediately; then a thorough diagnostic workup is initiated. Frequent reassessments may help in establishing the diagnosis, as well as the patient's response to treatment and the need for continued care.

H. Diagnostic Studies in Pain Assessment

Ordering and personally reviewing the appropriate diagnostic studies as soon as possible is important. Often, starting empirical treatment of the pain is also imperative so that short-term pain relief and a path to eradicating or altering the underlying cause of the pain can both occur as soon as possible. For example, if a patient with metastatic lung cancer complaining of severe leg pain and chest pain is admitted to the emergency room, while the clinician is trying to elucidate the cause(s) of this patient's pain, a high potency oral or intravenous (i.v.) opioid should be started. Treating the pain as soon as possible will also help to facilitate the appropriate workup because the patient will be more relaxed and will be more able to tolerate the necessary workups and procedures.

Although rapid relief of the pain should always be the first goal in caring for a patient in pain, of importance is not losing sight of the need to understand the etiology of the pain so that the underlying cause can be treated. A reasonable workup should be initiated the day the patient presents with a new pain complaint to confirm the clinical diagnosis and to define the site and extent of the underlying cause of the pain. As a general principle, one should consider an approach to a diagnostic workup for pain that uses imaging tests, nuclear medicine technologies, and laboratory studies. This comprehensive

P.427

strategy may not always be helpful. Doing unnecessary tests is not only expensive, but this also can reinforce illness behaviors and patienthood in those with hypochondriasis. Only tests that have a direct bearing on the treatment plan should be ordered.

Providing specific guidelines for the diagnostic workup for each of the different types and locations of pain is beyond the scope of this chapter. However, using the patient with cancer and pain complaints as an archetype for considering the approach to deciding on a diagnostic workup for pain, in general, computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging represent the most useful diagnostic procedures. Although plain radiographic films are useful screening procedures, they should not be used to overrule a clinical diagnosis if they are negative. Evaluation of the extent of metastatic disease may help to discern the relationship of the pain complaint to possible recurrent disease; for example, the postmastectomy pain syndrome that occurs secondary to the interruption of the intercostobrachial nerve is not causally associated with recurrent disease.

IV. Principles of Treatment

Probably the two most crucial tenets of treating pain are the following: always believe that the patient's pain is real, and be optimistic that the pain can be alleviated when it is appropriately treated. The fact that the overwhelming majority of causes and presentations of pain are treatable is possibly one of the best kept secrets in clinical practice. Not knowing this and accepting pain can be an insurmountable obstacle to good pain management; when clinicians do not believe they can treat a problem, they may set lower standards or not even try at all, especially if they harbor negative attitudes about the patient or the treatment. Unfortunately, this is most strikingly seen in patients with acute or chronic severe pain, many of whom suffer from cancer. They do not receive opioids when their use is indicated, because of their doctors' attitudes about pain, medicinal opioids as illicit drugs, or the patients who may need this care (e.g., patients with a history of addiction or psychiatric patients).

That patients not believe that their pain is their fault is important; no suggestion should be made that they should have sought treatment sooner or that they should have used more appropriate or effective treatments. For patients to try home or folk remedies, over-the-counter drugs, or herbal or other alternative remedies (e.g., acupuncture) before seeking traditional help is not uncommon. Additionally, clinicians need to prioritize for each patient the use of treatments to eliminate or to modify any underlying disease process, to reduce pain transmission, or to dampen pain awareness or receptivity.

A. Approaches to Management

When deciding how to treat a patient's pain, current symptomatology and any current and past medical conditions must be considered. The most important aspects of a patient's pain that determine the treatment approach are (a) its severity; (b) its underlying pathophysiology (i.e., inflammatory, neuropathic); (c) its temporal nature (acute versus chronic); (d) its effects on physical, psychologic, and occupational function; and (e) any physical examination findings. These factors need to be considered in the context of the underlying disease process that is causing or is associated with the pain (e.g., cancer, appendicitis) and the patient's current and past medical history (e.g., AIDS, systemic lupus erythematosus). The nature of the pain and the patient's medical history are only part of the equation; the clinician also needs to consider the patient's personality and style in approaching illness, his or her past experiences with pain, and the current emotional state.

Although addressing specific syndromes (e.g., fibromyalgia, AIDS neuropathy) is beyond the scope of this chapter, providing an overview of the approach to the patient in pain; how elements of the pain history, medical history, and psychologic factors are used in determining treatment; the core principles of the neuropharmacology of pain treatment; and how these can be realistically applied in the clinical setting is possible.

|

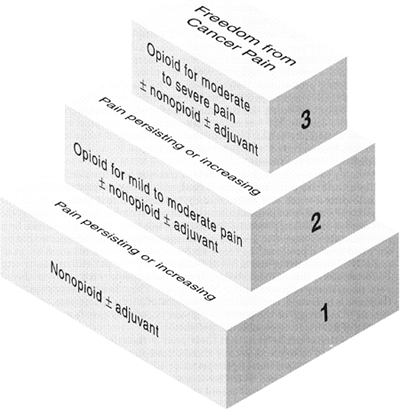

FIG. 28.1. The World Health Organization three-step cancer pain treatment ladder. |

P.428

B. Determinants of Management

Severity of pain. In 1990, the World Health Organization adopted the concept of the step-wise ladder approach (Fig. 28.1) to rating pain severity and to providing treatments that would be appropriate to the patient's degree of pain. Based on an extensive body of research in pain assessment and care, the ladder was developed to provide objective assessment and standardized treatment approaches. The conferees also clearly opined that opioids are necessary for the treatment of severe pain; they also concurred that opioids are likely to be needed for treating moderate levels of pain in some patients. However, now a consensus is seen among pain experts that, independent of other medical or patient factors, for mild pain (based on visual analog scale self-assessment scores ranging from 0 to 3), an NSAID or acetaminophen (Table 28.2) is indicated. For moderate pain, a higher dose of an NSAID or a combination (Table 28.3) of an NSAID and an opioid either a lower potency opioid (e.g., codeine, oxycodone) or a low dosage (but an equivalent amount of morphine equivalents; Table 28.4) of a higher potency opioid is indicated. In terms of morphine equivalents, in a population of patients having severe pain,

P.429

adequate relief will generally require more equivalents than should be needed for a patient with moderate pain. However, the clinician should remember that considerable individual variation is common. Severe pain deserves a higher potency opioid at a higher number of morphine equivalents than would be given for moderate levels of pain and, when the patient can tolerate it, an NSAID.TABLE 28.2. NONSTEROIDAL ANTIINFLAMMATORY DRUGS AND ACETAMINOPHEN ORAL DOSING FOR CHILDREN OR ADULTS WEIGHING MORE THAN 50 KILOGRAMS

NSAID Oral dosing (mg) Acetaminophen 500 650 q4h 975 q6h Aspirin 650 q4h 975 q6h Carprofen 100 t.i.d. Diflunisal 500 q12h Etodolac 200 400 q6 8h Fenoprofen 300 800 q6h Ibuprofen 400 600 q6h Ketoprofen 25 60 q6 8h Ketorolac tromethamine 10 q4 6h (max = 40/d) 30 q6h (i.m.) (for no more than 5 d) Meclofenamate 50 100 q6h Mefenamic acid 250 q6h Naproxen 250 275 q6 8h Abbreviations: i.m., intramuscular; NSAID, NonSteroidal AntiInflammatory Drug; t.i.d., three times a day. Almost contemporaneously with the publication of the World Health Organization ladder, the additive effect concept was introduced (i.e., combining an opioid and an NSAID when treating moderate to severe pain lowers the potential risk of side effects and toxicity from one or both

P.430

drugs). In general, the use of an opioid combined with an NSAID is accepted practice in the early phases of treatment of moderate to severe pain. However, an expanding literature on geriatric populations supports avoiding NSAIDs, with the exception of acetaminophen, when NSAIDs are needed (a) for chronic pain relief, regardless of the degree of pain; (b) in the treatment of acute pain when high doses would be needed; or, (c) when based on history, the patient is at high risk for renal failure or gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding. The most significant toxicities in both long-term and short-term use of NSAIDs in elderly patients are renal failure and GI hemorrhage. Whether cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors significantly reduce the risk of GI bleeding in the elderly or in patients with a past history of GI hemorrhage is still unresolved.TABLE 28.3. SOME OPIOID AND NONOPIOID COMBINATION AGENTS

Opioid Nonopioid(s) Codeine Acetaminophen Dihydrocodeine Acetaminophen, caffeine Dihydrocodeine Acetylsalicylic acid, caffeine Hydrocodone Acetaminophen Hydrocodone Ibuprofen Oxycodone Acetaminophena Oxycodone Acetylsalicylic acid Pentazocine Acetaminophenb Propoxyphene Acetaminophen Propoxyphene Acetylsalicylic acid, caffeine Tramadol Acetaminophen aTylox contains sulfites; Percocet 2.5/325 does not.

bTalacen contains sulfites.TABLE 28.4. APPROXIMATE EQUIPOTENT DOSING IN CHILDREN AND ADULTS WEIGHING MORE THAN 50 Kilograms FOR SELECTED OPIOIDS

Agent Oral Route Parenteral Route (in mg) Morphine 30 mg q3 4h (all day) 10 q3 4h Morphine (controlled release) 90 120 mg q12h Hydromorphone 7.5 mg q3 4h 1.5 q3 4h Levorphanol 4 mg q6 8h 2 q6 8h Meperidine 300 mg q2 3h 100 q2 3h Methadone 20 mg q6 24h 10 q6 8h Oxymorphone 1 q3 4h Codeine (with acetaminophen) 180 200 mg q3 4h 130 q3 4h Hydrocodone (with ibuprofen or acetaminophen) 30 mg q3 4h Oxycodone (with aspirin or acetaminophen) 30 mg q3 4h Pathophysiology of pain. Understanding the underlying causes and the subjective nature of the pain are critical to developing an effective treatment plan. To try to understand what is causing the pain is always necessary; if the underlying etiology can be treated, the likelihood of a more complete and longer term relief is greater. Again, this involves a thorough history and physical examination and possibly imaging and laboratory studies. For patients in whom a space-occupying lesion, trauma causing tissue or nerve damage, an abscess, or nerve compression exists, surgery, a nerve block, or some other procedure (e.g., corticosteroids to reduce edema) is likely necessary to bring relief.

Until an appropriate procedure can be performed, medication should be used to provide temporary relief. One commonly held belief is that, when such procedures are needed, pain medication should not be given because medication may mask any pain signaling a worsening of the patient's condition (e.g., a ruptured appendix in a patient awaiting appendectomy). No objective literature exists supporting this belief. In fact, randomized double-blind trials have shown that patients with severe acute abdominal pain awaiting surgery and given i.v. morphine have better outcomes that those given a placebo.

In addition to understanding the pathophysiology or disease process that is causing the pain, determining if the pain is primarily related to inflammation, a problem in the peripheral or central nervous system, or some combination of the two is also necessary. In general, an inflammatory process calls for the use of an NSAID or a corticosteroid. Pain that is severe or that is related to a neuronal process requires an opioid. In situations in which pain is due to a neuropathic process (e.g., peripheral

P.431

neuropathies, reflex sympathetic dystrophy, nerve damage), certain TCAs or selected anticonvulsants (e.g., gabapentin) are likely to be beneficial.Temporal nature of pain. Chronic pain requires a clearly delineated treatment plan that focuses on accurate diagnosis and goals of treatment. Although the same could be said about acute pain treatment, an approach that works to maximize physical; psychologic; social; and, if possible, occupational functioning and that respects the patient's views of treatment is most likely to be successful. Patients who suffer from chronic pain can benefit from the following:

Consultation with a pain specialist to address diagnostic issues and therapeutic options (for some patients ongoing care with that specialist may be indicated);

Psychologic care (e.g., antidepressants or anxiolytics for any depression or anxiety, individual psychotherapy addressing issues of chronic illness, support groups);

Physical therapy to maximize physical functioning;

Occupational therapy to address the activities of daily living and to overcome disability;

The expertise of a palliative care team for terminal disease. In some patients, their ongoing and severe pain may require surgery or a nerve blockade to bring relief.

Unfortunately, the acute versus chronic dichotomization remains a source of controversy. Acute pain is seen by some clinicians as being deserving of more aggressive management, whereas chronic pain is often approached as untreatable and as related to emotional problems or weakness. As has been noted, chronic pain is often comorbid with depression or anxiety, and, when chronic pain is effectively treated, depressive and anxiety symptoms improve. Although this is a correlational finding, many clinicians believe that such results indicate that some of the psychiatric symptoms are triggered by or are maintained by pain.

Concerns about the possibility of addiction with chronic opioid use have led some clinics to adopt an opioid-free policy; opioid-containing medications are not allowed. No clear evidence exists to support the idea that the length of opioid use leads to a higher risk of addiction. This view may be the result of confusion about the concepts of tolerance, physical or physiologic dependence, and addiction (see below).

Although some patients may require maintenance opioids and the dosages needed to relieve pain will likely increase over time, this is the result of a normal physiologic process (i.e., tolerance). This is important because only patients with a history of addiction appear to be at risk for addiction. For the patient at risk for addiction or for one who is currently using illicit drugs, an addiction treatment program should be a mandated part of the pain treatment plan when opioids are to be used. Opioids should never be excluded as a treatment option when they are likely to work. The physiologic and psychologic concepts related to opioid treatment and addiction are discussed below (see section IV.B.6). Remember that the first goal, whether with acute or chronic pain treatment, is the alleviation of the patient's pain in as rapid a manner as possible.

Physical examination findings. Unfortunately, physical examination findings are an unreliable indicator of the presence (or absence) of or the severity of pain. Patients can have acute severe pain or debilitating chronic pain with either no or minimal physical examination findings. This is best exemplified by ischemic bowel syndrome; in these patients, the pain complaints frequently are out of proportion to the physical examination findings. The presence of physical findings may help to guide treatment; in general, their absence should not. Clarifying and resolving a physical examination finding should not be a primary goal of treatment unless its treatment will promptly relieve the patient's pain.

Physical and psychologic functioning. Improving a patient's functioning should be at the core of any pain treatment plan. Determining the patient's current level of function and the appropriate goals of treatment is often a complex multidisciplinary task. Physicians; nurses; occupational and physical therapists; other allied health professionals; and, most importantly, patients and their families need to work together to develop a realistic treatment plan that considers the patients' views as central to any plan. This can be particularly important for certain cognitive tasks. When high opioid doses interfere with the performance or completion of these tasks, a patient may want to lower the dosage even when knowing greater pain is likely. Clinicians should facilitate this when requested to do so.

Concerns About Dependence, Tolerance, and Addiction. As a result of physiologic adaptation, physical or physiologic dependence often develops in patients who take opioids for greater than 2 to 4 weeks. If the opioid they are taking is not tapered when the time comes to discontinue it, a characteristic withdrawal syndrome may develop when the opioid is abruptly stopped; this is the morphine or heroin abstinence syndrome described in Chapter 10. As a result of increases and changes in affected opioid receptors, tolerance occurs, and, over time, increasing dosages of opioids are needed to maintain the same level of analgesia. Both dependence and tolerance are normal physiologic processes; neither per se is indicative of addiction. Opioid requirements are quite variable among individuals, and they are not directly related to a patient's weight, size, or age. Therefore, the rate at which physical dependence or tolerance develops is not predictable. Some patients may require increases in their total daily dosage that range from 5% to 25% every 2 to 14 days; others can remain on the same maintenance dosage for years.

By contrast, addiction is an abnormal pattern of behavior that is based on a belief that a drug will produce a desired euphoria or some other wanted physical or psychologic state. The addicted person believes that the drug is essential. Addicted individuals crave the drug, and they will use any means to obtain it, including endangering themselves and others. Continued use leads to social, psychologic, family, occupational, or physical problems. Interestingly, addiction can be present with or without the development of physical dependence, although, in general, increasing dosages are sought to achieve the initial euphoria.

As was noted above, only addiction-prone persons have a meaningful likelihood of becoming addicted to opioids that are taken therapeutically for pain relief. One prospective study followed approximately 14,000 patients who received opioids and found that, among patients with no prior history of addiction, the risk of addiction was 0.4% when opioids were taken for the relief of acute pain. Among those in remission from opioid addiction, about 30% relapsed (i.e., they returned to opioid misuse).

Patients sometimes develop tolerance to an opioid dose after as little as 5 to 7 days. After a short time, they may complain of inadequate pain relief, anxiety, irritability, or even withdrawal symptoms. They will request and sometimes demand that their dosage is increased or will come to the doctor's office saying they ran out of medication because they needed rescue doses or that they used a family member's pain medicine or alcohol for relief. When their pain is relieved, they do not seek the drug; they function normally and display no other signs of addiction. This pattern is called pseudo-addiction. It is a recognized behavior pattern that understandably results from the development of tolerance.

P.432

C. Specific Pharmacologic Treatments

Overview. Understanding that the pathophysiology of the disease process is causing the patient's pain can be a key element to a successful pharmacologic treatment plan. A basic step is determining whether the pain is primarily inflammatory in origin, a problem in the peripheral

P.433

or central nervous system, or some combination of these two. In general, an inflammatory process calls for the use of an NSAID. As was noted earlier, severe pain or pain related to a neuronal process usually requires an opioid.To treat any pain-related process other than tissue damage or inflammation, neuronal activity needs to be modified. In most patients with severe pain and in a number of patients with moderate pain, an opioid or some combination of medicines (e.g., a benzodiazepine, an anticonvulsant) is needed to decrease the patient's level of pain perception adequately and, as a result, their experienced level of pain. These medications modulate the activity of opioid receptors and the release of endogenous opioids. Opioids, and to some extent dopamine, act in the cortex and on some subcortical structures to alter pain perception. In neuropathic pain (e.g., peripheral neuropathies, reflex sympathetic dystrophy, nerve damage), selected TCAs or anticonvulsants are indicated. Most treatment plans for moderate to severe pain involve the consideration of inflammatory and neuronal processes and therefore combination therapy.

NSAIDs. NSAIDs include selective COX-2 inhibitors (e.g., celecoxib, rofecoxib, valdecoxib), acetaminophen, and standard or traditional antiinflammatory agents (Table 28.2). These agents all provide pain relief through their actions on prostaglandins and other modulators of tissue inflammation. Because acetaminophen's direct effect on prostaglandins is not typical of the other NSAIDs and its effects on inflammation is considerably lower, some clinicians consider it separately.

Indications. In general, these drugs are indicated (a) for a mild to moderate level of acute or chronic pain (e.g., mild rheumatic or osteoarthritic pain, mild lower back pain) with use as a single agent, (b) in acute pain with a significant component of tissue inflammation (e.g., a sprained ankle that is swollen, tendinitis), (c) in combination with opioids for the treatment of moderate to severe acute or chronic pain (e.g., pain due to a lung tumor, a fractured ankle), or (d) for antipyretic activity (e.g., fever from infection or tumor).

Although NSAIDs are generally similar in their effectiveness, differences that may play a significant role in choosing among them do exist. In commonly prescribed dosages, acetaminophen is slightly less effective as an antipyretic and in reducing direct tissue inflammation, yet it has considerably less GI and renal toxicity. Other NSAIDs and selective COX-2 inhibitors are essentially identical in short-term and longer term treatment efficacy, but, in patients who require these drugs chronically, the selective COX-2 inhibitors may have a lower risk for gastritis or GI hemorrhage. Despite some remaining degree of controversy over the costs and benefits, selective COX-2 inhibitors are in greater demand than ever. This may be partly because new interventions are sometimes helpful in patients with chronic pain. Because the risk of GI hemorrhage is low when the exposure to NSAIDs is short-term, the additional costs of selective COX-2 inhibitors may not be justified for acute pain treatment.

Acetaminophen. Acetaminophen has been studied in both acute and chronic pain treatment and in many different patient populations. It is effective as a first-line agent for mild to moderate acute and chronic pain and as a second drug for use in combination with an opioid for moderate to severe pain. In both acute and chronic use, it carries a significantly lower risk of GI hemorrhage, other bleeding problems, or renal insufficiency and renal failure compared with standard NSAIDs. As such, it should probably be tried first. In addition, unlike standard NSAIDs, it is not an established cause of hypertension, urticaria, GI reflux, or gastritis.

Metabolism. Acetaminophen is primarily metabolized by the liver. It should be prescribed at lower dosages or avoided altogether

P.434

in patients with significant liver disease or in those with lower glutathione stores available for phase 2 conjugation (e.g., diabetes mellitus, significant alcohol consumption). Because some elderly persons may have reduced hepatic oxidative or conjugative capacities, initial dosing with two-thirds of the standard adult dosage should be considered. Although acetaminophen is a useful alternative to NSAIDs in patients who have impaired creatinine clearance or renal function, NSAIDs are not necessarily an alternative to acetaminophen in patients with impaired liver function because of the potential risk of bleeding (decreased hepatic production of clotting factor).Contraindications. In a patient with adequate liver function, acetaminophen is a safe and effective treatment. However, when used in excessively high doses or in the setting of heavy alcohol use, even for short binge periods, it can result in irreversible liver failure and death. If either of these situations is suspected, the patient should be brought to an emergency room immediately. After an overdose of 15 pills, if a patient is not given N-acetly cysteine within approximately 4 hours, a significant number of patients will develop irreversible hepatic damage and perhaps failure. Liver transplantation may be necessary (see Chapter 3).

Standard NSAIDs and selective COX-2 inhibitors. These are quite comparable in efficacy. They are both effective for inflammation, the relief of mild to moderate pain, and the potentiation of the actions of an opioid in moderate to severe pain. However, these agents generally have a higher percentage of patients who will develop some or serious side effects. As was noted, in patients who require these drugs chronically and in those who are at high risk of GI bleeding, the selective COX-2 inhibitors have a slightly lower risk of GI discomfort, gastritis, or hemorrhage. If they carry less risk of GI hemorrhage with short-term use in those who are not at high risk for GI hemorrhage (e.g., no concomitant use of high-dose corticosteroids) is not clear.

Both classes of NSAIDs carry a significantly greater number of side effects and toxicity than does acetaminophen. The major side effects of NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors are GI hemorrhage, other bleeding problems, gastritis or gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), urticaria, hypertension, and renal insufficiency and renal failure. As a result, in cases of both acute and chronic pain, acetaminophen should be tried first. However, for the development of sudden inflammation (e.g., a twisted ankle) or as an antipyretic (e.g., for higher fevers, tumor-related fever), these drugs are superior to acetaminophen.

Metabolism. NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors rely on both hepatic and renal metabolism. The hepatic cytochromes (see Chapter 29) that metabolize these drugs can easily be affected by interactions with other drug classes, thus resulting in either a longer or shorter duration of action. Because some elderly persons may have reduced hepatic oxidative or conjugative capacities, initial dosing with two-thirds of the standard adult dosage should be considered. Acetaminophen is a useful alternative in patients who have impaired creatinine clearance or renal function.

Contraindications. This class of medications should, in general, be avoided in patients with significant active hepatic or renal disease, but each case needs to be carefully evaluated. In patients who have a history of recurrent GI hemorrhage or other bleeding problems, NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors should be stopped, if at all possible, and chronic opioid and other alternatives for pain relief should be considered in consultation with a pain specialist.

Opioids. Opioids are the current mainstay of severe pain management, and they are needed in certain cases of moderate level pain. Unfortunately,

P.435

as a result of a variety of misconceptions about their medicinal use, they are underused or are used ineffectively. This is unfortunate because opioids are effective and they have a wide therapeutic index. When they are used appropriately and side effects are anticipated and treated, most patients with moderate to severe acute pain obtain relief from these medications.Mechanism of action. Systemically administered opioids act in a variety of ways by binding to central opioid receptors1. A decrease in the level of pain perception occurs; this is a central action the pain perception threshold is raised to a higher level. Independent of their direct effect on pain perception, opioids also decrease anxiety and reduce the sympathetic outflow that some patients experience with severe pain. Like endogenous opioids, some opioids produce a sense of euphoria that may counteract some of the depressive effects of pain. This euphoria is sustained for only a few days after the initiation of treatment; opioids are not a useful treatment for depressive symptoms, even in patients suffering from chronic pain.

Indications. Opioids are the principal treatment for severe pain; they may also be needed for certain patients with moderate levels of pain. Although they are generally used in combination with an NSAID, opioids may be used alone when NSAID use poses a significant risk of side effects. They are also indicated for use in chronic pain when the long-term use of an NSAID for mild to moderate pain would pose a significant risk of GI bleeding, hypertension, or renal failure. In 2000, the American Geriatrics Society recommended that elderly patients who require long-term pain medication should be given an opioid, rather than an NSAID, to reduce the likelihood of these complications. The American Geriatrics Society recommendation is recent, and opioid use in chronic pain management remains a controversial area.

Metabolism. Opioids rely on hepatic and renal clearance for their metabolism and elimination. Because any central nervous system active drug's effect is also determined by receptor activity in the central nervous system, the brain also plays an important role, especially in the length of the intended effect of the drug and in central nervous system-related side effects (e.g., sedation, nausea, myoclonus). Patients with impaired cognition, dementia, and delirium are at the greatest risk of central nervous system-related side effects. Patients with impaired renal function are at the greatest risk for myoclonus. In both groups, the patient's starting dosage should be approximately two-thirds of that of other adult patients. These patients should also be frequently assessed for side effects.

How to prescribe opioids. Opioids are prescribed based on a set of pharmacologic equivalents that uses morphine sulfate as its standard, the half-life of the particular agent, and the route of administration. As a general rule, opioids should be administered by an oral or i.v. route, because intramuscular and subcutaneous administration are painful and their absorption is variable. Intravenous routes have a more rapid onset and shorter duration of action. Therefore, for patients with acute severe pain or for patients who develop breakthrough pain, an i.v. route is preferable. Because no first-pass effect is seen in patients who receive opioids parenterally, the same quantity will be more potent when given as a parenteral dose than is an oral dose of the same drug. In general, the parenteral dose of an opioid is one-third of the oral dose.

P.436

For the treatment of acute pain, 10 mg of morphine i.v. every 4 hours (or its equivalent) is recommended as a starting dose. The patient should then be reassessed in approximately 30 minutes and should be given additional medication based on the reduction of the patient's objective pain rating, with zero pain as the goal of treatment. Each additional administration should be given as a rescue dose every 2 hours i.v. until pain relief is achieved. The total dosage required over the first 24-hour period should then be tallied and divided into a standing dosage regimen. Even after the first 24 hours (and throughout the treatment course for patients with serious progressive or chronic illness), rescue medication should be available, and its use should then be added to the standing 24-hour dosage.

Once pain relief has been achieved, the patient's medication should be adjusted to the most convenient dosing regimen for that individual whenever possible. In general, this means long-acting oral forms of opioids (e.g., MS Contin or Avinza2, methadone, Oxy Contin, fentanyl). The fentanyl subcutaneous patch or the lollypop, which is absorbed through the buccal mucosa, provides an alternative to oral medication for those who cannot swallow oral medication. Likewise, liquid morphine (e.g., Roxinol) can be given to those who cannot swallow pills.

All patients who are started on an opioid and who have a functional GI tract should be started on a bowel regimen (e.g., motility agents and increased dietary fiber3) to prevent constipation. In addition, they should be advised to increase their intake of fluids. Because constipation will occur throughout the use of an opioid, this medication should be continued until the opioid is stopped.

Hydroxyzine. Some clinicians prescribe oral hydroxyzine (500 to 1,000 mg) to potentiate the analgesic effects of morphine sulfate and to reduce any morphine-induced urticaria.

Physiologic dependence and tolerance (also see section IV.B.6). Patients who take opioids for greater than 2 to 4 weeks will probably develop physiologic dependence, meaning that withdrawal symptoms and signs will develop if their opioid is suddenly stopped. Tolerance occurs when, as a result of the up-regulation of opioid receptors, increasing dosages of opioids are needed to achieve or to maintain the same intended effect. Both are normal physiologic processes, and neither is indicative of addiction.

As noted earlier, patients may develop tolerance after only 5 to 7 days at a certain dosage level. Opioid requirements are quite variable among individuals, and they are not clearly related to a patient's weight, size, or age. The rate at which physiologic dependence or tolerance develops is not predictable. Some patients may require increases in their total daily dosage ranging from 5% to 25% every 2 to 14 days, whereas others can remain on the same maintenance dosage for years. No therapeutic ceiling exists for opioids4; daily dosages of as high as 35,000 mg have been reported.

Side effects and their treatment

Respiratory depression results from the effects of opioids on the medullary respiratory center. Aside from addiction, this is

P.437

probably the most feared side effect among many clinicians. Clinical experience suggests that this fear is unfounded; respiratory depression is an extremely rare occurrence (less than 0.025% of patients), and fear of it probably results in the undermedicating of many patients with acute pain.Defined as a respiratory rate of less than 8 breaths per minute, this side effect appears to be limited to opioid-naive patients who have significant lung or central nervous system disease and then only during the first dosage. After a patient has received one dose with no significant decrease in respiratory rate or two doses when the respiratory rate is 12 or greater, no risk of future occurrence is present. Confusion about this danger probably occurs because of the potentially fatal accidental respiratory depression that happens in tolerant heroin addicts who mistakenly use an extremely high dose of concentrated heroin.

Naloxone, a short-acting opioid antagonist, should only be used when the respiratory rate goes below 6 per minute, when it becomes irregular or agonal, when an overdose is suspected, or when the respiratory depression is accompanied by oversedation or unresponsiveness. This is because the use of naloxone can precipitate severe withdrawal symptoms and the worsening of pain control. In most patients, if one dose of the medication is withheld and then the dosage of opioid is decreased, the episode will resolve and will not recur. In situations where respiratory depression has been documented, the dosage should be increased more slowly than it would normally be.

Constipation is the most common opioid side effect (greater than 40%); it can occur at any point in treatment, and it is independent of the route of administration. Constipation results from the actions of opioids at receptors in the gut. It is best prevented by recommending the following when opioid use is initiated: starting a motility agent; advising an increase in the daily intake of fluids by 25%, unless contraindications to doing so are present; and increasing fiber intake.

Clinicians should inquire about constipation at each visit. When patients report constipation, they should be advised to increase physical activity and fluid intake and to start using a daily stool softener (e.g., docusate sodium), and they should have the dose of their motility agent increased by 50% or should start a stronger one (e.g., magnesium citrate, lactulose). Constipation per se should not be a reason for decreasing the dosage of the opioid or for the use of naloxone. Rather, it calls for more aggressive management of the constipation while still providing adequate analgesia.

Nausea occurs in 5% to 10% of patients during the first 24 to 96 hours of treatment, independent of any that is related to constipation. It is generally self-limited, and it can usually be treated with supportive treatment (e.g., hydration, light diet). When medication is necessary, the short-term use of haloperidol, 1 mg twice daily, or lorazepam, 0.5 mg twice daily, is usually effective.

Myoclonus is a syndrome of uncontrollable sustained clonic jerking movements throughout the extremities and facial muscles that occurs as the result of an excess of the opioid metabolite 6-mercaptopurine. Myoclonus is quite rare, and it usually occurs in patients who are seriously ill or who have impaired renal function. Treatment involves lowering the dose of opioid or widening the time interval between doses, i.v. hydration, or, when needed, low doses of benzodiazepines. When myoclonus occurs, consultation with a pain specialist is recommended.

Sedation can occur when an opioid is first started, when rapid dosage escalations are made, when hepatic or renal metabolism is impaired, or when the patient becomes more ill. The most common occurrence of sedation is seen during the first 72 hours; it is usually self-limited. When sedation extends beyond this initial period, discussions between clinician and patient should take place regarding the benefits of pain relief and balancing them with the side effect of sedation to find an approach consistent with the patient's life-style. The elderly are at greater risk for excess sedation, and their dosage increments should be slower, if possible, than those seen with younger adults.

When pain persists and it is severe, extremely high doses of opioids are sometimes needed for relief. In some cases, the required high doses may cause stupor or unconsciousness as a side effect ( double effect ). In patients for whom the intended goal of treatment is pain relief, rather than sedation, hastened death, or euthanasia, the ethical principle of double effect provides for continuing this dosage, but only with the patient's or surrogate's consent.

P.438

Pain treatment in patients with addiction and those at risk for relapse. As was noted above, opioids are frequently underused or are ineffectively used because of a variety of misconceptions about their medicinal use. Probably the biggest roadblock to their use is a concern about causing addiction. This largely results from the negative attitudes of many people in society toward addicts, in which medicinal opioid use is incorrectly equated with illicit narcotic use. Because of this, fears of triggering addiction during medicinal use, even in those with no prior history of addiction or misuse of drugs, abound. These fears need to be overcome by more education and training in medical school and residency and by further research that addresses these obstacles. Unfortunately, the recent upsurge in the illicit use and theft of the long-acting oral opioid Oxy Contin has increased the public's negative attitudes toward more liberal availability of medicinal opioids.

Tolerance per se occurs when, as a result of the up-regulation of opioid receptors, increasing dosages of opioids are needed over time to achieve the same intended effect. Both are normal physiologic processes, and neither is indicative of addiction. As opposed to those with tolerance, addicts seek greater dosages to achieve a greater sense of euphoria or high. Patients who are drug seeking will often go to several different providers so they can obtain an ample supply, will lie about lost prescriptions, and will often return for refills before the expected date.

Distinguishing addiction from tolerance. Some patients are quite demanding and irritable when they need medication to avoid the symptoms of withdrawal or because they are in greater pain as a result of the development of tolerance. However, once they receive the proper dosage of opioid to relieve their pain, these behaviors resolve. Patients who are not suffering from addiction will also not crave the drug nor exhibit dangerous behaviors to obtain it. In addition, no evidence of impairment is observed in social, psychologic, family, occupational, or physical functioning as a result of its use.

In an interesting set of studies looking at whether patients would try to give themselves extra doses of morphine when patient-controlled anesthesia is used for severe pain relief, no patients (i.e., those with no prior history of addiction or without traits associated with addiction) had any pattern of extra use nor did they exhibit any drug-seeking behavior. Although this research is limited, it seems to support the view that the risk of

P.439

unanticipated addiction is quite low and that it should not cause a clinician to avoid its use in patients who lack a prior history of addiction.Treatment approach for patients with a history of addiction and those at risk of relapse. Patients with a history of addiction or who are currently using illicit drugs or alcohol deserve the same right to pain relief as those who are not suffering from addiction. They also need to be involved in a treatment program to manage their addiction or prevent a relapse. Making treatment of the addiction a condition for prescribing opioids to such persons is reasonable; however, withholding opioids because of the clinician's concerns about addiction is not reasonable when they are needed.

The dangers of escalating illicit drug use and relapse are quite real. As was noted previously, some studies have shown relapse rates of about 30% in at-risk persons, whereas other studies have found that 10% to 20% of patients using heroin before pain treatment increased their use of heroin shortly after starting pain treatment.

A workable approach to the treatment of addiction is referral to a drug and alcohol treatment program that allows its clients to take pain medication. This may actually be quite problematic because many programs do now allow continued use, and many local alcoholics and narcotics anonymous groups are adamantly opposed to members using medicinal opioids or psychotropic medication. Even with a successful referral, regular contact between the clinician managing the pain and the addiction treatment program is of importance.

Selected anticonvulsants and TCAs. Further discussion of the use of these agents is beyond the scope of this chapter, which is focused on the generalist clinician. Discussion with a pain specialist or clinic should be considered for more information about the longer term use of these agents.

D. Nonpharmacologic Treatments for Chronic Pain

Although no single approach to the nonpharmacologic treatment of chronic pain has received universal acceptance, some general principles and approaches appear central to those that enjoy some degree of acceptance, especially in multidisciplinary pain clinic settings. Most clinicians agree that nonpharmacologic treatments do not work when the pain intensity is already quite high. Among the approaches that may be considered as an adjunct to medication for moderate to severe pain are biofeedback (using electromyography or digital skin temperature); hypnosis (see Chapter 23); acupuncture, which is thought by many to work through release of endogenous opioids; diversionary activities or distraction; improved physical conditioning and exercise; meditation; and relaxation techniques (see Chapter 14). These and other techniques alone or in combination with medication can be part of effective self-management strategies.

V. Barriers to Pain Assessment and Adequate Pain Management

Lack of knowledge about pain assessment methodology is one of the common barriers associated with inadequate pain treatment. Physicians, patients, and the public, through a series of well-validated surveys, have defined the numerous barriers that interfere with adequate cancer pain management. These barriers have been categorized broadly as patient related, physician related, and institution related.

The patient-related barriers include (a) a reluctance to report pain, (b) a reluctance to follow treatment recommendations, (c) fears of tolerance and addiction, (d) concerns about side effects, (e) beliefs that pain is an inevitable consequence and that it must be accepted, (f) fears of disease progression, (g) fears of injections, and (h) culture-specific ideas about the causes and meanings of pain.

Closely allied to these patient-related obstacles are physician-related barriers. One study reported that when patients rated their pain as moderate to

P.440

severe, oncology fellows failed to appreciate the severity of the problem in 73% of their patients. In two studies, the discrepancy between patient and physician evaluation of the severity of the problem was a major predictor of inadequate relief. Knowledge deficits in cancer pain assessment and treatment are the norm more than the exception. Several studies have revealed an extremely low correlation between self-evaluation of clinical skills in pain therapy and the correct responses to clinical vignettes.

Institutional barriers include the lack of a language of pain and the failure to use validated pain measurement tools in clinical practice. The lack of time committed to pain as a priority, the lack of economic resources committed to its treatment, and the serious legal restrictions to drug prescribing and drug availability add further impediments to adequate pain treatment. These impediments have been widely discussed in the literature. When these barriers are found, specific programs need to be instituted to provide the framework for change.

VI. Additional Help

Help for referrals or patient support may be found by contacting the American Academy of Pain Management (209-533-9744; http://www.aapainmanage.org/), the American Pain Foundation (888-615-7246; http://www.painfoundation.org/), or the American Chronic Pain Association (916-632-0922; http://www.theacpa.org/).

ADDITIONAL READING

Averbuch M, Katzper M. Gender and the placebo analgesic effect in acute pain. Clin Pharm Ther 2001;70:287 291.

Beecher HK. The powerful placebo. JAMA 1955;159:1602 1606.

Bressler LR, Geraci MC, Schatz BS. Misperceptions and inadequate pain management in cancer patients. Ann Pharmacother 1993;25:1225 1230.

Caldwell JR, Rapaport RJ, Davis JC, et al. Efficacy and safety of a once-daily morphine formulation in chronic, moderate-to-severe osteoarthritis pain: results from a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial and an open-label extension trial. J Pain Sympt Manage 2002;23:278 291.

Cherny N, Portenoy R. The management of cancer pain. CA Cancer J Clin 1994;44:263 303.

Cleeland C. Documenting barriers to cancer pain management. In: Chapman C, Foley K, eds. Current and emerging issues in cancer pain. New York: Raven Press, 1993:321 330.

Cleeland C, Gonin R, Hatfield A, et al. Pain and its treatment in outpatients with metastatic cancer. N Engl J Med 1994;30:592 596.

Eliot L, Butler J, Devane J, et al. Pharmacokinetic evaluation of a sprinkle-dose regimen of a once-daily, extended-release morphine formulation. Clin Ther 2002;24:260 268.

Foley K. Competent care for the dying instead of physician-assisted suicide. N Engl J Med 1997;336:54 58.

Ingham J, Foley K. Pain and the barriers to its relief at the end of life: a lesson for improving end of life health care. Hospice J 1998;13:89 100.

Jacox A, Carr D, Payne R. Management of cancer pain. Clinical practice guidelines. Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, 1994.

McCarberg BH, Barkin RL. Long-acting opioids for chronic pain: pharmacotherapeutic opportunities to enhance compliance, quality of life, and analgesia. Am J Therap 2001;8:181 186.

Portenoy R, Thaler H, Kornblith A. Symptom prevalence, characteristics and distress in a cancer population. Qual Life Res 1994;2:183 189.

Sees KL, Clark HW. Opioid use in the treatment of chronic pain: assessment of addiction. J Pain Sympt Manage 1993;8:257 264.

Von Roenn J, Cleeland C, Gronin R, et al. Physician attitudes and practice in cancer pain management. A survey from the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Ann Intern Med 1993;119:121 126.

1Although the actions of opioids are mainly central, some peripheral action may also occur, as is well demonstrated by the fact that, when administered locally (i.e., into a knee joint), binding to putative opioid receptors in the periphery produces pain relief.

1Avinza is a once-daily extended-release capsule formulation of morphine sulfate (30, 60, 90, 120 mg). Opening these capsules and sprinkling the combination of immediate-release and extended-release components onto soft foods (e.g., applesauce) is possible. Of importance is noting the fact that this formulation contains fumaric acid, which may cause renal toxicity, especially when dosing exceeds 1,600 mg per day.

3Generally well-tolerated sources of fiber include fruit juices (with pulp), raw fruits (with skins and seeds), raw vegetables, whole-grain cereals and breads, canned prunes or apricots, nuts, and dried figs and dates. Gas-producing foods should be avoided (e.g., beans, cabbage), even though they may be high in fiber.

4Because of its fumaric acid ingredient, the Avinza formulation of morphine sulfate has a maximum dose of 1,600 mg per day.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 37