Section 37. Project Charter

37. Project CharterOverviewThe purpose of Define is to ensure that

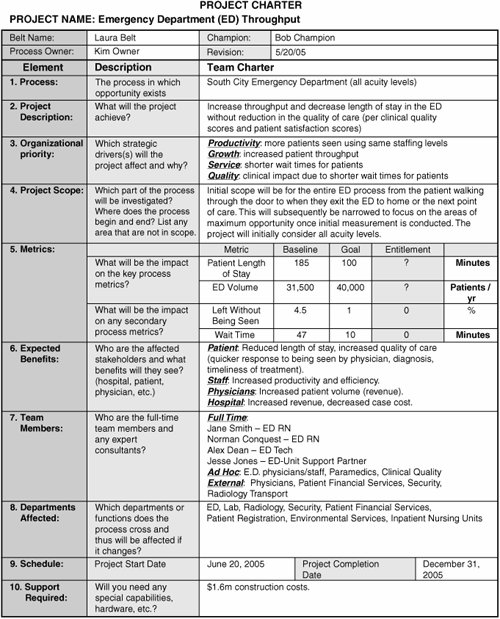

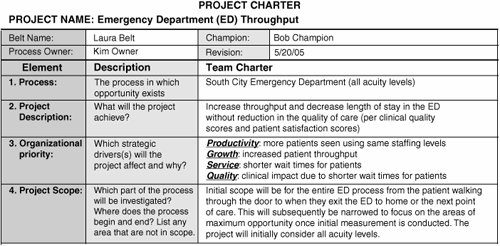

The Project Charter is a 12 page document to ensure all these elements are considered. An example Charter is shown in Figure 7.37.1 and enlarged in Figures 7.37.35. The Charter, in essence, represents a project contract between the Belt, Team, and Champion, defining the problem, scope, value, goals, and support required. Figure 7.37.1. An example of Project Charter. The Charter is not just a tool for the current Team conducting the project, it is a tool used to help

With these possibilities in mind, it is important that the Charter is clear and readily understandable by anyone in the business who reads it. LogisticsAt a Program level, there are typically a multitude of potential projects for a business to undertake. Once a potential project is identified, it needs to enter the project selection process to be judged in its merits versus all other projects.[54] To have enough information to make this judgment, an owner of the project (who typically would later become the Project Champion) would construct the draft Project Charter.

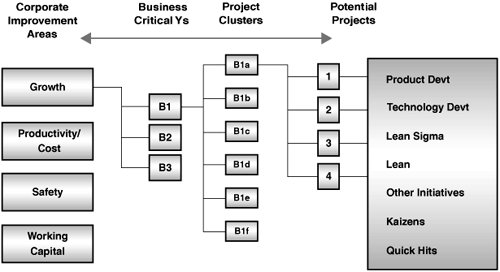

After the project is selected, the Champion reviews the draft Charter with the nominated Project Leader (Black or Green Belt) to build in more detail and specifically to agree on the appropriate Team members. After this is complete, the Belt and Champion review the Charter with the selected Team during the first Team meeting to make the final tweaks prior to commencement into Define. The Project Charter is a living document through the Define and Measure Phases of the project, although generally the only elements to be updated during this period would be the metrics and scope (as more understanding of the process is gained), along with minor Team changes if there is a significant scope change. After Measure, the Charter typically becomes "locked-in" for the remainder of the project. RoadmapThe Project Charter is generally completed in linear order from top to bottom as follows: Header InformationThis includes basic information about the project. It is critical that each Charter has a designated Belt and Champion identified. All the Process Owner(s) must be identified, and after the draft Charter is complete, they should be bought into the objectives of the project. The Revision Date reduces confusion over the latest version of the Charter. 1. ProcessThis should identify the process in which the opportunity exists. It needs to be specific enough to identify location (site) if appropriate. 2. Project DescriptionThis should describe what the project is intended to achieve. It should be based around key performance goals and generally takes the form of "Improve the metric from A to B," for example, "Improve the RTY for the process in unit ABC from 80% to 95%" or "Improve the number of lines on-time and complete from 92% to 98% for resupply." The description should only be a statement of the problem or goal and should not infer or include a solution. 3. Organizational PriorityThis should identify which strategic drivers (the highest level business metrics) the project affects and why. Movement of the key performance metric (listed in the Project Description) should relate back to the high-level organizational goals. This can be done with the aid of a Goal Tree, as shown in Figure 7.37.2.[55] If there is no clear linkage, then the viability of the project should be in question. Typically each organizational goal is listed along with the impact of the project on that particular goal, as shown in Figure 7.37.3.

Figure 7.37.2. Linking the project goals to the organizational goals.[56]

Figure 7.37.3. An example of a Project Charter elements 14. 4. Project ScopeThis identifies the part of the process to be investigated and where this process section begins and ends. It is imperative that the Team lists any areas that are not in scope. The scope is one of the most important sections of the Charter to ensure the Team stays focused on the task in hand, but also to truly gain consensus of the size of the undertaking. One of the most demoralizing things a Belt or Team can experience is to think that they have completed a project, only to be told they have missed a key part of the process later by the Project Champion or Process Owner. To avoid this it is important to set additional boundaries for the Team to remain focused. This is done by identifying "in frame" and "out of frame" criteria, for example:

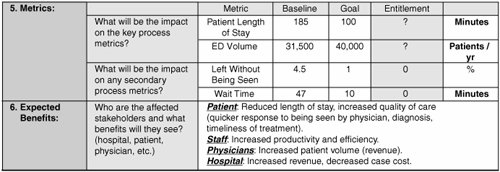

A common mistake made early in Lean Sigma Programs is to make the scope of a project too large (sometimes known as "boiling the ocean"). Knowing what is too large is a skill that is tricky to teach and generally in the early stages of a Program it is best to rely on an external consultant or skilled Master Black Belt to act as the guide. 5. MetricsLean Sigma as a methodology that is heavily data-based. This begins with the Charter. The Metrics section captures the desired impact on the key measures of process performance. Successful projects tend to focus on improving a limited set of key metrics (typically one to three). Other key metrics might be listed as secondary "balance" metrics and might be listed with the intent of not adversely affecting them. For each metric there should be well-defined Baseline, Goal, and Entitlement values. In the early stages of the project (before the Measure Phase), the baseline is taken from whatever data is available historically or from a short run study of the key metrics. The reason to understand the current performance level at this point is to judge whether the project is worth doing. This can typically be justified with a high-level understanding of the key metrics, but the baseline is later replaced with more rigorous data from the Measure Phase. The use of Entitlement as a Goal-setting concept is one of the strongest components of Six Sigma (and subsequently Lean Sigma) and underpins the breakthrough mentality. Entitlement, for a metric, is the best value that the metric could ever achieve; the ultimate in performance, for example:

When Goals were set in traditional process improvement projects, it was generally done by looking at current performance and demanding a small improvement, 1% or 5% for example. Another alternative might have been to conduct benchmarking of competitors and setting the goal as the best of their performance levels. There are two things wrong with these approaches, namely:

Use of Entitlement really drives a different mentality in Goal setting. It might be impossible to achieve Entitlement itself (often not), but a goal of a change of halfway from current performance to Entitlement[57] or even three-quarters of the way is absolutely possible in most processes and really drives a different mindset. This kind of change cannot be achieved by "holding our breath" and genuinely requires a fundamentally different approach. It also sends a strong message to the Team, Operators, and the rest of the organization that this is a serious endeavor and requires significant effort and resource.

The values of Baseline and Goal (and sometimes Entitlement) can change throughout the project based on gaining a deeper understanding by use of the tools. If values change, then ensure that the Charter is updated and the Revision date is amended. 6. Expected BenefitsThis should list all the affected Stakeholders and the benefits they will see from the project. Benefits generally fall into three categories:

Any Financial benefits need to be clearly defined with a mathematical description of how to calculate the impact in dollars. The calculation formula must be accepted and supported by the Program Finance representative. If the method of calculation is not well defined in the beginning of the project, there is a struggle at the end to determine the financial impact. Each project must have a measurable, tangible benefit to the Customer or it isn't the right project to undertake. When the project is completed, the Team should be able to go to a Customer and confirm that the project impact was "felt." 7. Team MembersThis should list the full-time Team members and any expert consultants (these can be listed as "ad-hoc"). Team members are typically part-time assistants to the effort; the Black Belt is the only full-time member. The pitfall here is to make the Team too large. The optimum Team size is four to six key members, but recognize that not all Team members need to participate in all of the activities. Figure 7.37.4. An example of Project Charter elements 56. The importance of including this section on the Charter is so that

With these points in mind it is important not to just identify Team members by title only, but to specify both name and title. The required level of Team member time must be released to the project by their management, and the Team members themselves must be informed of their participation in the project as promptly as possible. 8. Departments AffectedAll departments affected by the project need to be consulted. To this end, this section should list all departments or functions that the process crosses and will be affected if it changes. Process Owners in the affected departments or functions should have sight of and ability to make inputs to the Charter. 9. ScheduleAlthough a detailed project schedule needs to be maintained separately by the Belt, it is important to agree to the time boundaries for the project (i.e., the Project Start Date and End Date). Projects early in the life of the Lean Sigma Program take somewhere from four to six months (including the training period) to complete. Later when Belts have had project exposure, the duration should be 34 months. It is possible to accelerate this further using tactically placed Kaizen[58] events, an approach referred to as "K-Sigma" which is beyond the scope of this book.[59]

10. Support RequiredThe Team should list needs for any special capabilities, hardware, and so on. In fact, this is somewhat of an "acid-test" for the Project Team. Any capital requirements listed early in the project are generally indicative of a solution in mind. This is not a good thing, because the Charter should reflect only the problem and not any preconceived notions of solution. Typically, this box remains empty, unless the Team deems a particular skill set or additional tools necessary to conduct the project. Figure 7.37.5. An example of Project Charter elements 710. After the Charter is complete, it should be revisited by the Team to give it a "sanity check" as follows:

Also, the Charter should be quickly revisited each time new understanding of the process is gained during Define and Measure to make subtle changes if necessary. The Champion and Process Owner should agree upon any and all changes. The Charter typically evolves during Define and Measure, but after the sign-off of the Measure Phase it is unlikely to undergo any further changes for the remainder of the project. As mentioned previously, completion of a strong Project Charter is a crucial part of the Define Phase of the Project and its value should not be underestimated. Weak Project Charters are almost certainly the biggest cause of any Project failures. |

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 138