Tools for Securing Home Networks

| |

The first and most efficacious step toward securing home networks, including those that connect with enterprise networks, is to ensure that each computer has capable, up-to-date anti-virus protection. The anti-virus system should not only scan the system for executable files with viruses and monitor executable files arriving from the Internet or from removable media; it should also be capable of scanning e-mail attachments and files with embedded macros. Because connecting via a VPN will enable the enterprise network to seem to be part of the local network, home users need to be assured of good virus protection on the enterprise network.

Home computers may become infected through several routes with Trojan Horse software that provides remote access to attackers . The Trojan Horse may arrive before the anti-virus vendor's update is installed. The offending remote control code may be part of a game or file swapping program that a user installs or discovers intentionally. An attacker who installs the remote control program may take over an inadequately patched home-based server. Once NetBus or SubSeven or Back Orifice is installed, anti-virus software will, at best, only find it when it does a full system scan. In the worst case, it will fail to realize that any infection exists.

This is when a personal firewall product with outbound application control capabilities is essential. These products prompt users the first time an application needs to send traffic across the network. The name of the program (or service), perhaps the pathname of the application, and additional information may be provided, and the user will be prompted to specify whether or not to block the traffic. If the user chooses to block the traffic for an application, rules will be created in the firewall to prevent future traffic. Some of these products have a database of known illegitimate remote control programs and automatically block their ability to transmit, which is a good idea for situations where a user might not recognize the names of dangerous executable files. In some products, the firewall silently blocks traffic it identifies as dangerous. This approach has the advantage of minimizing confusion on the part of users who have no basis to decide what applications should be allowed to communicate, but it increases reliance on the vendor to keep the database of dangerous applications up to date.

As we've pointed out in previous tutorials (see "Coping with Home Network Security Threats," the previous tutorial), it's easy to overestimate the vulnerability of home computers and home networks to direct outside attacks. A single computer, even one connected to an always-on, high-speed access service, will rarely be running a Web server, mail server, FTP server, or other traditional hacker target, and therefore usually will not be vulnerable to a direct exploit. A home network that uses network address translation (NAT) to share a single IP address among multiple devices generally isn't vulnerable to outside attack, provided none of the devices is acting as a crackable server. Some vendors even describe NAT gateway products as "firewalls," though that's an overstatement. NAT boxes maintain a table that matches incoming address and port number combinations with more or less arbitrary local address and port number combinations, while packet filtering firewalls maintain tables of rules for forwarding or denying packets on each port.

Setting the inbound rules on a personal firewall is only crucial sometimesin particular, if you're running server processes for remote clients . Of course, not all services are obviously services. Peer-to-peer software, including Instant Messaging (IM) and teleconferencing require running server components . A recently uncovered and patched vulnerability in Windows XP attacked a service in the Universal Plug and Play (UPnP) system, designed to support automatic installation of remote devices. It's not intuitive to imagine that being able to connect with a printer across the Internet requires your desktop machine to operate a service on ports 1900 and 5000.

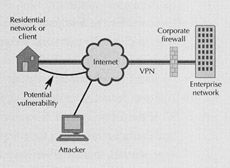

Potential Vulnerablity of VPN. An external attacker with remote control access to a residential client may be able to access the enterprise network with the employee's access rights.

Services aren't a danger if they're implemented properlythe UPnP vulnerability was based on an input buffer overflow, as many other attacks are. Implemented properly, UPnP represents no vulnerability to an external takeover attack.

Another issue regarding personal firewalls is peace -of-mind. Assessing a home network's vulnerability is more complex than most configuration jobs for home PCs, and the stakes can be high for workers who have enterprise data on their home network and for remote workers who connect with their offices. Enterprise network managers who define the standards for remote connections, as well as individuals who set up their own remote connections to the office, would be well advised to install personal firewalls that block unsolicited incoming connections and unintentional outbound remote control connections. (Note that Microsoft's Internet Connection Firewall, included with Windows XP, isn't designed to block this sort of dangerous outbound traffic.) For enterprises looking for consistency and manageability, some personal firewall products have central configuration options. The real trade-off for enterprises with remote workers is the safety net provided by personal firewalls versus the complication, support requirements, and perhaps a performance penalty that comes with the personal firewall.

When the stakes are really high, software-based personal firewalls will likely be perceived as incommensurate with the task of securing remote workers. In these cases, the enterprise will probably install centrally controllable standalone firewalls and dedicate the computer and perhaps even the network access connection to secure applications.

Fitting In With The VPN

A remote-access VPN is designed to authenticate users accessing their office network over the Internet and to encrypt all the traffic over the link. One way to look at a VPN is as an opening through the enterprise firewall. If an attacker can install remote control software on a home computer, the VPN may serve as a path into the enterprise network. On the other hand, the home firewall needs to recognize that VPN traffic is legitimate and to stay out of the way. Most common personal firewall products can be configured to coexist with VPNs.

You might think of firewalls as the walls of a building, with locked doors corresponding to particular port and protocol combinations that permit certain types of entry and exit. Extending this image, Intrusion Detection Systems (IDSs) listen for someone to jiggle the locks and try the doorknobs to see if unauthorized entry is possible. Where firewalls apply rules to particular ports and protocols, network-based IDSs monitor all inbound traffic to identify "attack signatures."

Both firewalls and intrusion detectors create events when they detect violations. The least common denominator destination for events is the log file. Various products can log some or all of the following data: the source, destination, and port addresses of particular packets and the rules they broke; the complete contents of offending packets; inferences about the type of attack that the offending traffic indicates; and the configuration history of the software. Products that emphasize intrusion detection often display onscreen alerts when they identify attack conditions. Some products send e-mail notices of alert conditions.

For some people, flashing alerts whenever an automated port scan or nmap episode occurs is more than they care to know about the dangers of the Internetthey're content to go about their business as long as they're protected. Others take script- kiddie attacks to heart, and feel obligated to run whois and trace the ISP of the source address of every log event. It's important for the future self-government on the Internet that irresponsible users be held in check, but there's a certain amount of danger in auto-responding to every alert with e- mails to the abuse departments of ISPs. The primary reason for caution is the presence of "false positives" in firewall and intrusion detection logs.

Lawrence Baldwin, who operates www. mynetwatchman.com, has closely studied personal firewall logs over the last year and a half. A nice compromise between ignoring events that appear to be attacks and blasting away at ISPs a hundred times a day when a Code-Red-type siege is underway is to follow the instructions at the myNetWatchman site and send your logs to them. Their scripts filter out the false positives, identify spoofed source ad-dresses, and track down the real sources of attack traffic. Then they pack up all the evidence and send it to ISPs in a form that's hard to ignore.

False Positives

Here are some of the most common causes of false positive events for residential clients as identified by myNetWatchman: If you request a response from a sufficiently slow server, your firewall may time out and no longer maintain the connection in its table. The slow-to-arrive response now looks like an unsolicited transmission, requiring an alert to the user. Furthermore, Web pages often have components that must be collected from multiple geographically distinct servers, including Content Delivery Networks (CDNs), such as Akamai's, and advertising servers, such as doubleclick's. Thus, any of a number of slow sources may falsely appear to be an attack.

A second common false positive is the "proximity probe." When you start to request data from a large, widely distributed Web site that employs a load balancer with a DNS lookup, multiple sites issue proximity probes. The ICMP normal responses to these probes help identify the closest or fastest server for providing the requested data. This traffic arrives at the personal firewall from addresses that no request was sent to, so they appear to be probe events on TCP port 53.

Another common source of false positives is the stale IP cache. If you have a dynamic IP address, you inherit all the cached baggage of the address' former lessee. Certain games and peer-to-peer file sharing programs are notorious for blasting out thousands of requests to expired addresses. Each of these requests hits the personal firewall log as an attempted attack.

Another type of false positive is associated with Microsoft's Internet Information Server (IIS), the Web server built into all NT-based versions of Windows. Apparently when NetBIOS over TCP/IP is enabled on a public- facing interface, which is common, though it hardly seems useful, IIS attempts to identify the NetBIOS names of clients that make HTTP requests. These queries will show up as hostile probes on the personal firewalls.

There's a lot of scanning and port mapping and scripted exploit execution underway at any given moment. It's relatively painless to protect against such activityin fact, to be equipped with not only a belt but also a couple of pairs of suspenders. Some reasonably good personal firewalls are available free for the download, and the most expensive ones are just $50. Popular and reliable NAT routers with firewall capability included are available for less than $100. The real danger may be the amount of time users spend installing software, defining firewall rules, trouble-shooting dicey installations, waiting for tech support, and flaming unresponsive ISPs that don't shut down obvious miscreants. One last word of advice: Try to be as well-informed as possible before asking hardware, software, or ISP help desk people about the potential sources of rogue Internet traffic. You don't want to be classified as a GWF, short for "Gomer with Firewall."

Resources

Lawrence Baldwin's useful discussion of firewall false positives can be found at www.dslreports.com/forum/remark,2169468.

The Home PC Firewall Guide (www.firewallguide.com) has high-quality background information, along with numerous pointers to comparative reviews of these products. One good one is at www.boran.com/security/sp/pf/pf_main20001023.html, written by Sen Boran.

Another valuable comparison, "Getting Personal with Firewalls," was written by Curtis Dalton in the January 2001 issue of Network Magazine (page 100, www.networkmagazine.com/article/NMG20010103S0010/1).

If you want to see the center of the Gomer-with-firewall universe, tune in to the grc.security newsgroup at news.grc.com. The postings aren't always accurate and reliable, so you'll have to sort through them with a wary eye.

This tutorial, number 164, by Steve Steinke, was originally published in the March 2002 issue of Network Magazine.

| |

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 193