More Challenging Simultaneous Games

Games involving dominant or strictly stupid strategies are usually easy to solve, so we will now consider more challenging games.

Coordination Games

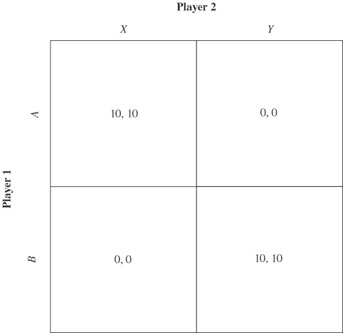

How would you play the game in Figure 16? Obviously you should try to guess your opponent’s move. If you’re Player One you want to play A if your opponent plays X and play B if she plays Y. Fortunately, Player Two would be willing to work with you to achieve this goal so, for example, if she knows you are going to play A she will play X. In games like the one in Figure 16 the players benefit from cooperation. It would be silly for either player to hide her move or lie about what she planned on doing. In these types of games the players need to coordinate their actions.

Figure 16

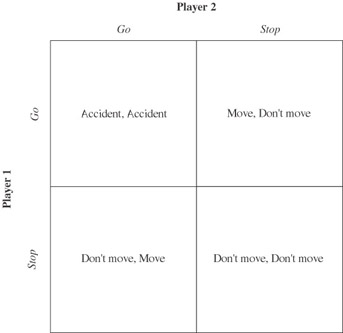

Traffic lights are a real-life coordination mechanism. Consider Figure 17. It illustrates a game that all drivers play. Two drivers approach each other at an intersection. Each driver can go or stop. While both drivers would prefer to not stop, if they both go they have a problem.

Figure 17

Coordination games also manifest when you are arranging to meet someone, and you both obviously want to end up at the same location, or where you’re trying to match your production schedule with a supplier’s deliveries. Figure 18 shows a coordination game that two movie studios play, in which they each plan to release a big budget film over one of the next three weeks. Each studio would prefer not to release its film when its rival does. The obvious strategy for the studios to follow is for at least one of them to announce when its film will be released. The other can choose a different week to premiere its film, so that both can reap high sales.

Figure 18

Technology companies play coordination games when they try to implement common standards. For example, several companies are currently attempting to adopt a high-capacity blue-laser–based replace-ment for DVD players. Consumers are more likely to buy a DVD replacement if there is one standard that will run most software, rather than if they must get separate machines for each movie format. Consequently, companies have incentives to work together to design and market one standard.

In game theory land you do not trust someone because she is honorable or smiles sweetly when conversing with you. You trust someone only when it serves her interest to be honest. In traffic games a rational person would rarely try to fake someone out by pretending to stop at a red light only to quickly speed through the traffic signal. Since coordination leads to victory (avoiding accidents) in traffic games, you should trust your fellow drivers. In all coordination games your fellow player wants you to know her move and her benefits from keeping her promises about what moves she will make. The key to succeeding in coordination games is to be open, honest, and trusting.

Trust Games

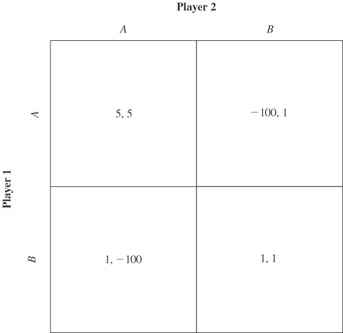

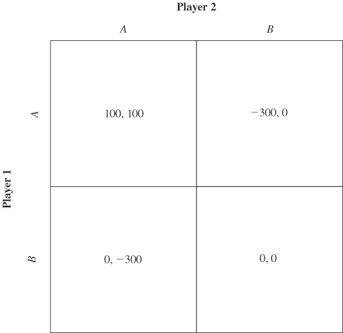

Trust games are like coordination games except that you have a safe course to take if you’re not sure whether your coordination efforts will succeed. Figure 19 illustrates a trust game. In this game, both players would be willing to play A if each knew that the other would play A as well. If, however, either player doubts that the other will play A, then he or she will play B. Playing B is the safe strategy because you get the same moderate payoff regardless of what your opponent does. Playing A is more risky; if your opponent also plays A, you do fairly well. Playing A when your opponent plays B, however, gives you an extremely low payoff.

Figure 19

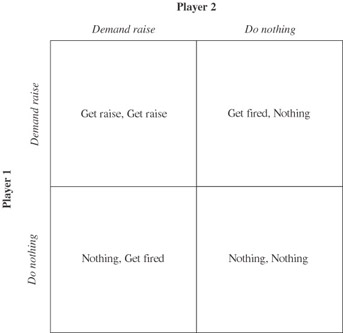

Figure 20 illustrates a trust game where both you and a coworker demand a raise. In this game your boss could and would be willing to fire one of you, but couldn’t afford to lose you both. If you jointly demand a raise, you both get it. Alas, if only one tries to get more money, he gets terminated.

Figure 20

In any trust game there is a safe course where you get a guaranteed payoff, and there is a risky strategy that gives you a high payoff if your fellow player does what he is supposed to. A simple example of a trust game is where two companies work together on a research project and both must complete their research for the project to succeed. The safe course for each company to take would be not to do any research, and thereby ensure that neither company has anything to lose in a joint venture. If your company does invest in the project, it receives a high payoff if the other firm fulfills its obligations. If, however, the other firm does not complete its research, then your firm loses its investment.

Let’s consider a trust game played by criminals. When two individuals hope to profit from an illegal insider-trading scheme, they enter a trust game. Imagine you work at a law firm. Through your job you learn that Acme Corporation intends to buy Beta Company. You and only a few others know of Acme’s plans. When Acme’s takeover plans become public in a few days, you’re sure that the value of Beta stock will rise. Obviously, you would like to buy lots of Beta stock before its price increases, but unfortunately, if you did buy Beta stock you would be guilty of insider trading and might face a prison term. Of course, you go to prison for insider trading only if you get caught, and the way not to get caught is to have someone else buy the stock based upon your information. You first consider suggesting to your father that he buy Beta stock. You realize the stupidity of this plan because if the SEC (the stock market police) found out that your father bought the stock, they might become suspicious. You need to get someone with whom you do not have a strong connection to buy the stock. You therefore propose to a friend you haven’t seen since high school that he buy lots of Beta stock and split the profits with you. You and your friend have now entered into a trust game. Of course, the safe course of action would be not to engage in the illegal insider-trading scheme at all. If you engage in the insider-trading scheme you have very little chance of getting caught if neither of you does something stupid like brag about your exploits to a friend. If, however, the two of you carry out your plan, you each could suffer a massive loss if your fellow player proves untrustworthy.

Workers who go on strike are also often engaged in trust games. Frequently, if all the workers show solidarity and remain on strike until their demands are met, then management usually will have to give in, and the workers will be better off. Going on strike is risky, though, for you will be hurt if your fellow workers abandon the strike before management submits to the demands.

The obvious solution to any trust game might be for all parties simply to embark on the risky course. A small amount of doubt, however, might make the risk unbearable.

Doubts within Doubts: A Confusing Recursive Discourse

Doubts are deadly in trust games. Indeed, even doubts about doubts can cause trouble. For example, assume that both you and your friend have the temperament to successfully execute an insider-trading scheme. Your friend, however, falsely believes that you are a blabbermouth who would discuss your schemes with casual friends. Your friend would consequently not engage in insider trading with you even though you both are trustworthy.

Figure 21 shows the mayhem unleashed by doubts within doubts. Obviously, in the game in Figure 21 the best outcome would occur if both people played A. Small doubts, however, could make this outcome impossible to achieve. To see this, imagine that there are two kinds of people, sane and crazy. Assume that a crazy person in the game in Figure 21 will always play B. A rational person will play whatever strategy gives him the highest payoff. Let’s assume (perhaps unrealistically) that you are sane. If you think your opponent is crazy, then obviously you will play B and not get the high payoff. Let’s assume, however, that you know your opponent is rational, but you also know that he mistakenly believes you to be crazy. If he thinks you are crazy, he will play B and thus you should too. Even if you are rational and your opponent is also rational, the only reasonable outcome, if your opponent thinks you are crazy, is for both of you to play B. Even though both parties are rational and believe the other person too is rational, if you doubt that they know you are rational, you should play B. This, of course, means that if your opponent believes that you believe that your opponent believes that you’re crazy, then he should play B and consequently so should you. Thus, to achieve the ideal outcome in a trust game it’s not sufficient for both people to trust each other. There must also be an infinite chain of trust where you trust that they trust that you trust that . . . that you’re trustworthy.

Figure 21

Outguessing Games

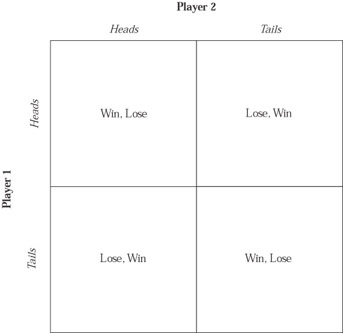

The opposite of a coordination game is an outguessing game, the classic example of which is the matching pennies game shown in Figure 22. In the matching pennies game two players simultaneously choose either heads or tails. Each separately writes down his choice. If both players make the same choice, then Player One wins, while if they choose different sides, then Player Two wins.

Figure 22

Imagine that before both players write down their choice they talk to each other about strategy. If you’re Player Two you obviously want to lie to Player One. Player One wins by matching your choice. Thus, if you intend to play heads, you should tell him you would play tails so he will try and match by playing tails, and you then win. Actually, this might not work since the other player knows you have an incentive to lie. If you are known always to lie, then people will acquire valuable information from your statements. For example, if I always lie and told you I was going to play tails, you would know that I really was about to pick heads. The matching pennies game, thus, shows that to truly deceive people (or at least provide them with no useful information) you must occasionally tell the truth. Perhaps this is why it is claimed that the Devil mixes the truth with his lies. If Satan always lied, we could achieve salvation by doing the opposite of what he says. Of course, if we always followed the strategy of doing the reverse of what Satan asked, he could take advantage of our poor gamesmanship and bring about our damnation (which results in one getting a very low payoff) by telling the truth. In contrast, if you’re in a coordinating game with God, then it would be a reasonable strategy on God’s part always to tell the truth because both God and you want to achieve the same outcome. Consequently, God is honest while Satan is deceptive, not merely because God is good while Satan is evil, but because the different games they are playing necessitate different strategies.

Armies often play outguessing games with each other. During World War II, the Germans knew that the Allies would try invading Nazi-occupied Europe from Britain. The Nazis didn’t know, however, exactly where the Allies would land. Had the Nazis learned the landing locations, they would undoubtedly have deployed a massive number of troops at these points and probably repelled the invasion. The Allies, consequently, desperately tried to keep the invasion plans secret. Indeed, the Allies did more than this and spread false information to the Nazis. The invasion of Nazi-occupied Europe was successful because the Nazis thought the Allies were going to play tails when the Allies were really intending on playing heads.

In baseball, pitchers and batters play outguessing games. Batters try to predict what kind of ball the pitcher will throw, and pitchers try to hide their strategies. Pitchers always vary their throws to keep batters off balance and ensure that they never know what to expect. There would obviously be no advantage to a pitcher and batter negotiating over what kind of ball the pitcher should throw, since these players have conflicting goals. Pitchers and catchers usually signal to each other what kind of pitch will be thrown. The batter would be greatly helped if his team could decode these signals and transmit them to the batter. In outguessing games you can always gain by successfully spying on your opponent.

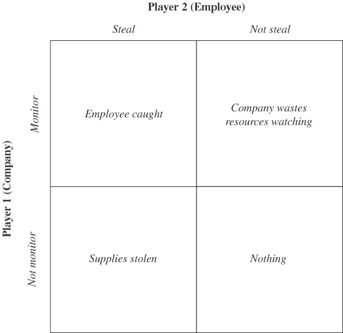

An outguessing game manifests when a company tries to catch a pilfering employee, as illustrated in Figure 23. The boxes are marked a little differently in this figure because the outcome, not the individual payoffs, is written in each box. Let’s imagine that the company can secretly watch the supply room to see if someone is stealing stuff. It’s too expensive for the company to monitor the room all the time, so they only occasionally have someone watch it. The company’s strategy is either to monitor or not monitor. The employee enjoys stealing but only if he doesn’t get caught. The employee’s strategy is to steal or not steal. Obviously, the employee wants to steal only when the company isn’t watching. Conversely, the company wants to watch only when the employee steals. Remember, in simultaneous games both sides move at the same time and must make their move while still ignorant of what their opponent will do. Thus, each side must predict what the other side is up to.

Figure 23

Randomness manifests in all outguessing games. To see this in our stealing game, assume, falsely, that there is no randomness and the outcome of the game is for the employee never to steal. In this case the company would never bother watching. Of course, if the company never watched, the employee would always steal. It is therefore unreasonable to assume that the employee will never steal. Furthermore, if the employee always steals, then the company will always watch, which of course will lead to the employee never stealing, which in turn will cause the company never to watch, which will . . . which will . . . The only stable outcome in this game is for the employee to sometimes steal and for the company to sometimes watch.

American taxpayers play an outguessing game with the IRS. People who cheat on their taxes and get caught pay fines and sometimes go to jail. People who cheat on their taxes and don’t get caught, well, they just pay lower taxes. When a rational taxpayer decides whether to cheat on his taxes he thus must try to guess the likelihood of the IRS auditing him.[5] It’s costly for the IRS to audit taxpayers. They only bother to do it to catch tax cheats and punish personal enemies. Thus, taxpayers and the IRS are in an outguessing game. You want to cheat only if you’re not going to get audited, and the IRS wants to audit only if you’re going to cheat. The only reasonable outcome involves randomness, where sometimes people cheat, and sometimes people get audited. As with all outguessing games, there is no point in trying to communicate your move to the IRS. Writing them a letter explaining that they shouldn’t audit you because you have properly filled out your taxes is probably not going to reduce the chances of their coming after you. Similarly, while the IRS would probably believe a self-made claim that you had cheated on your taxes, issuing such a pronouncement is probably not an optimal strategy. In outguessing games you want to hide your moves.

When approaching an intersection at night, it would be a very bad idea to turn off your lights to keep the other drivers from guessing your intentions. In outguessing games, however, you always want to turn your lights off. This is because while in coordination games you are better off if your opponent knows your move, in outguessing games you want to hide your actions from your opponent. Or even better, you want to spread false information. Negotiations are pointless in outguessing games since both players have strong incentives to lie. The key to winning outguessing games is to hide, never trust, and always strive to deceive.

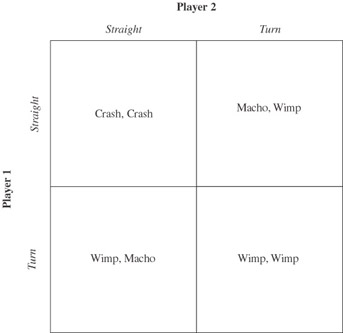

Games of Chicken

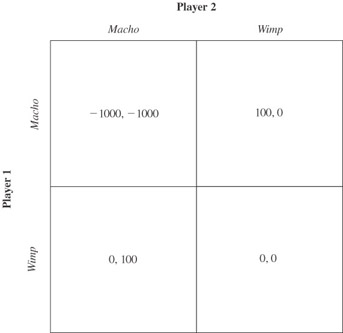

In the classic game of chicken, shown in Figure 24, two cars drive straight toward each other. The first driver who turns loses. Of course, if neither car swerves then both drivers lose even more. The best outcome for a player results when he goes straight and his opponent turns. In this situation the winning driver will be known as macho while the other driver will be considered wimpy. The worst outcome for either player manifests when an accident is caused by both drivers going straight. Consequently, a rational player will turn if he believes that his opponent is going to drive straight.

Figure 24

In a chicken game, therefore, you win by convincing your rival that you will never turn.[6] Consequently, perception is reality in the game of chicken. Chicken is not just a game about who is more macho, but also about who more exudes an air of machismo. Each player wants the other to believe that he is so macho that he would rather die than give in. If you can convince your opponent that you are indeed macho, you will win the game and thus be proven macho.

Insane players have a massive edge in the classic chicken game, for would you ever want to prove that you are more willing to risk death than a crazy person is? What if you suffer from the handicap of being considered sensible, however? Would anyone believe that a sensible person would ever adopt a strategy of never turning? Yes, having a strategy of never turning is rational if your opponent will always turn. If Player Two believes that Player One will always drive straight, then Player Two should always turn. Furthermore, if Player One knows that Player Two believes that Player One will never turn, then Player One should indeed not turn. The players’ beliefs about what they think will happen are self-reinforcing. If everyone thinks that one of the players will never turn, then that player’s best strategy will indeed be never to turn. Again we see that in game theory land players often adopt strategies based upon what other people think they are going to do.

Excite@Home’s Chicken Attempt[7]

Most negotiations don’t lead to chicken games. Imagine that I own a good that you want to buy. If we fail to reach an agreement, we lose the benefit of the trade but don’t necessarily destroy anything of value. A chicken game can exist only when the players might get into an accident, and an accident necessarily entails destruction.

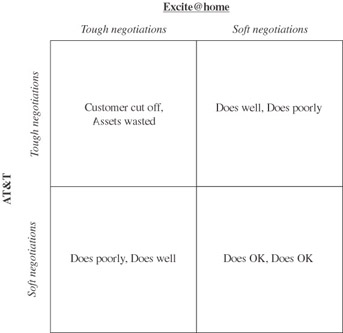

When Excite@Home fell victim to the tech crash, its bondholders attempted to play a chicken game by creating the possibility of an accident. AT&T used Excite@Home to help provide Internet ser- vice to many AT&T customers. When Excite@Home faced bankruptcy, AT&T started negotiations to buy Excite@Home’s assets. Excite@Home’s creditors were unhappy with AT&T’s offer, however, so they started playing chicken.

The creditors got legal permission to close down their Internet services and strand many AT&T subscribers. The creditors believed that AT&T would suffer if many of AT&T’s Internet subscribers’ web access was terminated. By threatening to shut down, Excite@Home attempted to increase the value of their assets to AT&T. Figure 25 illustrates this chicken game. Each party can be either a tough or soft negotiator. Had Excite@Home not been able to quickly cut off services, then AT&T’s payoff if both parties were macho (top left box) would have simply been no deal. Excite@Home made this a game of chicken by causing AT&T to suffer in the event of the parties not reaching an agreement.

Figure 25

Imagine that I own a good worth $100 to you, so $100 is the most you would normally ever pay for it. Let’s further assume, however, that I have the ability to cause you $30 worth of damage, and I threaten to inflict this damage if you don’t buy my good for $125. As Excite@Home’s bondholders understood, having the capacity to inflict pain can increase bargaining strength.

Unfortunately for Excite@Home, they overestimated their ability to harm AT&T. AT&T was able to move their Internet customers quickly to other networks, thus greatly limiting the damage from an accident. After moving their customers, AT&T withdrew their previous offer for Excite@Home’s assets.

AT&T had what they thought was a long-term relationship with Excite@Home. In long-term business relationships you don’t generally try to increase your profit by threatening to inflict pain on your partner. Since Excite@Home was going bankrupt, however, its time horizon shortened, so it tried to maximize its short-term payoff, rightly ignoring any long-term reputation loss. As this example shows, you can trust your business partners not to exploit you only so long as your partner still cares about his reputation.

Free Rider and Chicken Games[8]

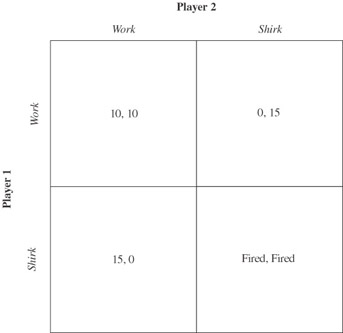

Free rider problems can cause chicken games to manifest. In free rider games players try to be lazy and benefit from the efforts of others. Consider the game in Figure 26. Imagine that this game came about because a boss assigned two employees to complete a task. Each employee can either work at the task or evade the job. If both people work, the task will be completed, and each employee will earn a payoff of 10. If both employees shirk, the job won’t get done, and both workers will be fired. To make this a free rider and chicken game, however, assume that if one employee works and the other shirks, the lazy employee who shirks gets a payoff of 15, while the stupid hardworking one gets only 0 (but doesn’t get fired.) Both employees want the other to do the work, but if either believes that the other will not work, she will work to avoid getting fired.

Figure 26

Both players would have an incentive to tell each other that they will definitely not do the work. If I can convince you that I won’t work, you definitely will so I can safely slack. Of course, you have the same incentive to convince me that you are going to slack. Consequently, neither of us should completely believe the other when we say we won’t work. It is therefore possible that neither party will work because each believes that the other might.

In both coordination and chicken games the players could coordinate their actions to avoid an accident. As you recall, in coordination games you always should believe the other party so avoiding bad outcomes is relatively easy. For example, assume that you’re a pedestrian at a crosswalk, and a driver signals for you to cross the street in front of his car. At this moment you and the driver are in a coordination game where the worst outcome would be if you both attempted to simultaneously cross the street. When the driver signals for you to go she is in effect telling you that he will stay put. Since the driver would have no sane reason for deceiving you about her intentions you should probably believe him and walk across the street, confident that you will avoid an accident. In chicken games, however, your fellow player has an incentive to exaggerate his commitment to going straight. Since both of you should always suspect the other might lie, an accident can occur because the two of you could not rely upon communication to avoid disaster.

I recall one real-life game of chicken I played with my sister when we were both young teenagers in which there was an “accident.” Our mother told us she was going out to the yard but was expecting an important call. She told us to be sure to answer the phone when it rang. (This game took place in primitive times before answering machines had invaded middle-class homes.) When the phone did ring, both my sister and I insisted that the other get the phone. This exchange continued until the phone stopped ringing. Our mother heard the phone but was unable to reach it before the caller hung up. She expressed anger and disappointment at my sister and me. This was clearly unfair, however, as she had created the game of chicken and should have anticipated the possibility of an accident. Had our mother clearly assigned responsibility for picking up the phone to only one of us, I’m sure it would have been answered.

Assigning clear responsibility can avoid accidents in free rider/ chicken games. Let’s reconsider the game in Figure 26, in which both employees want the other to do the work. Recall that there is some chance that neither player will do the work because each expects the other to complete the task. Now imagine a simpler game in which the employer splits the task in two. The boss pronounces that an employee who doesn’t complete his task gets fired. Now each employee will play a game where he gets, say, 10 if he works and gets fired if he doesn’t. Both employees should now work. Of course, since it’s often essential for people to work in teams in business, managers can’t always split responsibilities.

Chicken games also occur between firms rather than just within them. Imagine that two firms are considering entering a local market in which there is room for only one firm to operate profitably. In this example, each firm would want to convince the other that it was completely committed to staying in the market, but would also want to have plans to leave the market if the competition stayed in. Interestingly, each firm might welcome attempts by the other firm to spy on them.

Spying in Chicken Games

As you recall, in outguessing games you want to stop your opponent from spying on you. In outguessing games, if your opponent figures out your strategy, he always wins. In chicken games, however, if your opponent knows your strategy, and that strategy is one of machismo, then you will triumph. Thus, if you believe that you could put up a brave front, you should welcome your opponent’s attempts to spy on you.

Indeed, disaster would result if you tried to rebuff spying attempts. Imagine that you have told your opponent that you are definitely going to enter this small market. You hope he will believe you and not try to enter himself. But further imagine that your opponent sends a spy to your business to see if you are really planning to enter. If you turn away this spy, what should he believe? Obviously, if you know that his spy would report that you were indeed planning on entering the market, you would welcome him. Since you are rebuffing the spying attempt, however, your opponent should suspect that you have something to hide. The only thing that you would have to hide is your lack of commitment to entry. Not welcoming spies signals that you could be a wimp. Since perception is everything in chicken games, being perceived as a wimp will indeed make you wimpy. It is therefore vital in games of chicken never to openly stop your opponent from watching your actions.

The difference between counter-spying strategies in chicken and outguessing games comes about because in outguessing games a party always has something to hide. Regardless of what move a player plans to make in an outguessing game, she doesn’t want her opponent to become aware of her actions. Attempts at concealment in outguessing games tell your opponent nothing, since everyone would always try to hide everything in these games. In chicken games, however, a party wants to hide something only when she has a weak commitment to adopting the macho strategy. Thus, you can’t completely hide your actions from a spy in a chicken game because the very act of concealment signals your actions. Not allowing the spy in tells the spy everything she wants to know.

Chicken Treasure Hunts

A chicken game can result when multiple players seek a treasure. Imagine that a recently uncovered pirate’s diary indicates the existence of buried treasure somewhere on a small island. Let’s say the treasure would be worth $100,000 if found. Unfortunately, it would cost $70,000 to search the island and find the treasure. Since it would obviously be worth spending $70,000 to get a $100,000 treasure it would seem to be a good idea to search for the treasure. What happens, however, if two people know of the treasure’s existence? If they teamed up, they could split both the costs and the benefits. What if one party, however, wanted the whole treasure for herself? If both players spent $70,000 searching for the treasure, at most only one of them would find it. Spending $70,000 for a 50 percent chance of getting $100,000 is a terrible investment; even Las Vegas (but not government-run lotteries) would give you better odds. Consequently, if one party is genuinely known to be committed to searching for the treasure, the other party should not even try looking for it. If only one party looks for the treasure, then that player will make a nice profit. Thus, this treasure hunt is also a game of chicken where each party wants to convince the other that each is committed to the macho (searching for the treasure) strategy.

When multiple firms conduct similar research, they are often on treasure hunts. Under the U.S. patent system the first company that discovers some useful invention receives all the rights to that invention. If my company makes the discovery one day before yours, I receive the patent rights, and you get to explain to your stockholders why you wasted so much money on research.

How much should a company be willing to pay for a patent worth $10 million? They should be willing to pay up to, but not quite including, $10 million. Now imagine that multiple firms are simultaneously trying to get the same patent. If they all spend close to $10 million on the venture then most will lose money. It’s worth spending nearly $10 million researching the patent only if you know that your research will indeed result in your getting the patent. If multiple firms are vying for the same type of patent, your firm obviously can’t be sure that its research efforts will pay off. As a result, if you know that others are going for the patent, it might be optimal for you not to try.

Of course, the other firms would very much like for you not even to try. As a result they have a strong incentive to notify you that they are seeking the patent. Normally, we assume that companies like to keep research projects secret so other firms won’t steal their ideas. When playing patent chicken games, however, the optimal strategy is to broadcast your research goals loudly. As with any chicken game, firms will have an incentive to lie and exaggerate their commitment to getting the patent. If the firm sells stock, however, then securities fraud laws might prevent the firm from telling too grievous a lie about its research agenda.

For example, vaporware manifests because of chicken games. Vaporware is software that a company announces but doesn’t complete. Imagine that a $10 million market arises for a new type of business software. It would cost $7 million, however, for a company to develop this software. You want to capture this market, but you don’t want to develop the new software immediately. If your competition knew that you would take a year before starting to write the software, they would immediately start developing and capture the market for themselves. You could use vaporware, however, to reserve the market for future capture. You could falsely announce that your software would be ready in one year. This announcement, if credible, should scare away potential entrants.

The key to prevailing in a chicken game is to convince your opponent that you are committed to the macho course. You should welcome your opponents’ attempts to spy on you. If, however, you are certain that your fellow player is herself going to be macho, then your optimal strategy is to be a wimp so as to avoid an accident.

Games of Chicken and the Cuban Missile Crisis[9]

The Cuban missile crisis of 1962 was a game of chicken. The United States discovered that the Soviet Empire placed missiles in Cuba. Fortunately, America discovered the missiles before they became operational. Because Cuba was so close to the United States, the missiles greatly enhanced the Soviets’ military power. Absent these Cuban missiles, the United States could have struck the Soviet Empire with far more atomic weapons than the Soviets could hit America with. The United States had a greater capacity to strike over long distances than the Soviets did, and the United States had bases in Turkey, which bordered on the Soviet Empire. President John F. Kennedy demanded the removal of the missles and imposed a naval blockade on Cuba. Both the United States and the Soviet Empire had the choice of following a macho or wimpy strategy. For the Soviets, being macho meant not removing the nuclear missiles. For Kennedy, being macho meant invading, bombing, or blockading Cuba. If both players took the macho course, atomic armageddon might have resulted.

We now know that the Kennedy Administration gave some consideration to invading Cuba. Had the United States invaded Cuba, the Soviets might have responded by taking West Berlin, and had the United States then tried to free West Berlin, war might have broken out between the two superpowers.

It must have appeared to President Kennedy that the United States was in a much stronger position than the Soviets were because America’s capacity to hurt the Soviets was far greater than the Soviet’s capacity to harm America. To President Kennedy it must have appeared as if the two countries were playing the classic game of chicken, but with America driving a truck and the Soviets a small car.

Unknown to the United States, however, it appears that the Soviet agents in Cuba had operational battlefield nuclear weapons. The Soviets could not have used these weapons to strike the United States, but they could have used the weapons to attack invading American troops. An American invasion of Cuba might therefore have triggered an atomic response.

The existence of the Soviet battlefield nuclear weapons would have made it easier for the Soviets and Cubans to resist an American invasion. Had President Kennedy known of these weapons’ existence, he surely would have given less consideration to invading Cuba. So, in this game of chicken, while Kennedy thought the Soviets were driving a small car, they were really driving a truck.

Recall, in games of chicken you always want to convince your opponent that you will be macho. Since the battlefield nuclear weapons clearly made it more likely that the Soviets would be macho, the Soviets made a serious mistake in not informing President Kennedy about the weapons’ existence. The Soviet Empire collapsed because its rulers didn’t understand economics, so I guess it’s not surprising that they didn’t understand elementary game theory either.

In the end the Soviets backed down, at least publicly. The Soviets removed the missiles from Cuba in return for America’s pledge not to invade Cuba. Privately, America agreed to remove some missiles from Turkey. These Turkey-based missiles were obsolete and due to be removed soon anyway. The agreement between the two countries specified that if the Soviets told anyone about America’s promise to remove the missiles from Turkey, then America would no longer be bound to remove them. President Kennedy clearly wanted to be perceived as macho, and he no doubt feared that this perception would be tarnished if it were known that he had given away too much to the Soviets.

Winning Chicken by Burning Money

Burning money can be profitable![10] To see the advantages of burning money, consider the chicken game in Figure 27.

Figure 27

Obviously in this game each player would want to convince his opponent that he is committed to being macho. If, for example, Player Two believes that Player One will be macho, then Player Two will be a wimp, giving Player One his highest possible payoff. Player One could actually signal his commitment to being macho by burning money.

Let’s expand the game in Figure 27. First, Player One has the option of publicly burning $5. Second, both players simultaneously choose their strategy. Player One’s strategy consists of two parts: deciding whether to burn and choosing between A or B. Player One now has four possible strategies.

If Player One elects to burn $0 and be a wimp, then his payoff is $0, regardless of whether Player Two elects to be a wimp or to be macho. On the other hand, if Player One elects to burn $5 and be a wimp, then his payoff is –$5, regardless of whether Player Two elects to be a wimp or to be macho.

Burning $5 and being a wimp is a strictly stupid strategy. If you are going to be a wimp, you are always better off not burning $5. Thus, everyone should predict that if Player One does burn $5, he would not be a wimp. Hence, if Player Two observes that Player One burns $5, then Player Two should assume that Player One will be macho. If Player Two believes that Player One will be macho, then Player Two will choose to be a wimp. By publicly burning $5, Player One credibly signals that he will be macho.

Businesses have no need to actually burn money, however; for they can publicly waste funds. The best way for you to waste your money is to send it to me. Companies can also burn money by paying for celebrity endorsements. For example, to signal your commitment to enter a new market that could only profitably support one firm you could hire an expensive celebrity to star in commercials announcing your intentions. With luck, the pricey commercials will convince rivals of your absolute commitment to enter the market so your rivals will stay away.

Fixed-Sum Games

You can characterize games by their total payoff. In a fixed-sum game, what one player gets, another loses. Mathematically, in a fixed-sum game, the sum of the players’ payoff in each of the boxes adds up to the same number. Chess is a fixed-sum game in which if one player wins, the other must lose. Variable-sum games consist simply of all games that are not fixed sum. In variable-sum games the players can often benefit from working together.

In fixed-sum games cooperation is pointless because the player’s interests are diametrically opposed. In negotiations you seek to get something that makes you better off. If, however, my gain is your loss, then the fact that I want something necessarily means you shouldn’t give it to me.

You can consider a game to be like a pie. The players’ strategies determine the size of the pie and what percentage of the pie each player gets to eat. In variable-sum games the size of the pie varies, so there is room for both cooperation and competition. The players have an incentive to cooperate to make the total pie as large as possible and to compete to maximize what percentage of the pie they each get. In fixed-sum games outside forces fix the size of the pie, and the players fight over how much of the pie each of them gets to eat. Consequently, in fixed-sum games there is no room for cooperation.

Fixed-sum games can get nasty because you always want to inflict maximum pain on your opponent. Clearly, if his loss is your gain then you want him to suffer. For example, imagine that you and a coworker are up for a promotion that only one of you can get. If the only factor relevant to both payoffs is who gets the promotion, then the game is clearly fixed sum. In this game anything you could do to make your coworker look bad would increase your chances. Similarly, anything she could do to harm you would advance his interests. Thus, you would each benefit from sabotaging each other’s work and spreading degrading rumors about each other.

There are, however, very few fixed-sum games in business settings. In our promotion game we assumed that the only relevant consideration was whether you got the promotion. This assumption is clearly unrealistic, as it would be possible for you both to not get the promotion and to get fired. If both you and the coworker recognize that your promotion game was not fixed sum, then you would realize the benefits of agreeing not to make each other look bad.

Consider a market where only two firms sell widgets. These firms are almost certainly not in a fixed-sum game. It’s true that if one company takes a bigger percentage of the market, then the other company must lose market share. It’s possible, however, for the total market for widgets to increase or for the price each firm charges for widgets to rise.

Imagine that in an effort to reduce its rival’s sales, one company falsely announces that the use of widgets causes cancer. This announcement strategy would almost certainly harm the rival firm. If this game were really fixed sum, harming its rival would always help the announcing firm. Of course, announcing that a product you produce causes cancer is unlikely to be a winning strategy because firms are never really in fixed-sum games.

Politicians, however, do play fixed-sum games. Political candidates often run negative advertisements while companies almost never do because running for elected office is a fixed-sum game where only one candidate can win. Thus, anything that hurts your political rival helps you get elected. Imagine you’re running for office in a two-person race. You realize that if you run a negative ad it will make 20 percent of the voters think your rival is stupid. Of course, she will retaliate and run a negative ad that makes maybe 15 percent of the voters think you are a moron. Should you run the ad? Absolutely, it will increase your chance of winning this fixed-sum game. Now imagine that you run a company and are considering running a negative ad against a competitor. As before, if you run your ad your competitor will likewise retaliate. Should you publicly attack your rival? No! Even if you can harm your rival more than she could hurt you, you would both probably end up losing money. Running the ad would shrink the size of the pie your two firms divide.

Look to Interests

To win, you must know what you are playing. Different games require different strategies. The game you’re in is determined by the alignment of the player’s interests, so when starting a new venture ask:

-

Does everyone have the same objectives?

-

Would other players benefit from lying to me about their strategy?

-

Is the game fixed or variable sum?

-

Do I want my opponent to guess my future moves?

-

Am I better off being perceived as rational or crazy?

Mass Coordination Games

In the next chapter we will look at simultaneous coordination games that are played by millions of consumers. The outcome of these games often determines the fate of high technology companies.

Lessons Learned

-

A dominant strategy gives you a higher payoff than all other strategies regardless of what your opponent does.

-

A strictly stupid strategy gives you a lower payoff than some other strategies regardless of what your opponent does.

-

You should always play dominant strategies and never play strictly stupid strategies, and you should assume that your opponent will do the same.

-

You should be open, honest, and trusting in coordination games.

-

A small amount of doubt can make it impossible for two parties to trust each other.

-

It’s useless to negotiate in outguessing games.

-

In chicken games perception is reality, so you must do everything to convince your opponent that you are committed to the macho course.

[5]Shouldn’t a rational taxpayer realize the benefits his government provides him and thus gladly pay his taxes? No! If you alone didn’t pay taxes then the total tax revenue the government receives would be only trivially smaller. Consequently, by not paying taxes you would save a lot of money but not notice any reduction in governmental services. Shouldn’t a potential taxpayer worry that if many people didn’t pay their taxes then the government would have to cut back on services? Again, no! Your not paying taxes is certainly not going to cause many other people to not pay their taxes. (Especially because if you become a tax cheat you will probably not advertise your activities.) Furthermore, if many other people are not planning on paying their taxes there is probably nothing that you can do about it. Consequently, it is best for you to ignore whether other people will pay their taxes and just concentrate on how you can minimize your tax burden.

[6]Actually, most sensible people would be better off never playing the classic game of chicken. If a sensible person somehow found herself in such a game the optimal strategy would simply be to turn at the earliest possible moment. The classic chicken game assumes, however, that both players desperately want to be perceived as macho.

[7]CNET News.com (December 4, 2001).

[8]See Dixit and Skeath (1999), 110–112.

[9]Dixit and Skeath (1999) provide an interesting and readable game theoretic analysis of the Cuban missile crises in Chapter 13 of their textbook.

[10]See McMillan (1992), 73–74.

EAN: N/A

Pages: 260