Section 18.5. Improving Your Charts

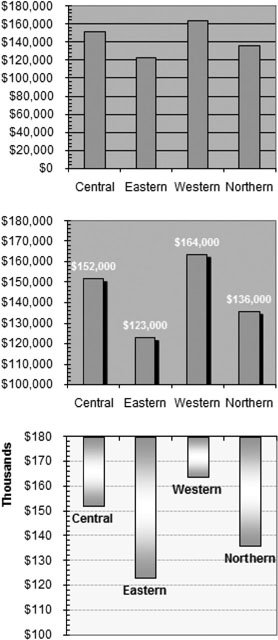

18.5. Improving Your ChartsSo far, you've learned the key techniques you need to make sure your charts tell the right story. However, Excel lets you do plenty more, including adding trendlines, data tables, and error bars, and tweaking 3-D perspective and shapes . In the following sections, you'll learn even more about how to make the perfect chart. 18.5.1. Controlling a Chart's ScaleMany people don't think twice about the scale they use when they create a chartinstead, they let Excel set it automatically based on the values their chart has been built from. There's nothing wrong with this laissez-faire approach, but if you know how to take control of your chart's scale, you can make important data stand out and make it easier for people looking at your chart to spot relative differences in data and understand overall trends. Usually, you'll be most interested in changing the scale of the value axis that runs on the left side of most charts. You can modify the scale of the value axis on most charts, including column charts, line charts, scatter charts, and area charts. (In a bar chart, the value axis actually runs horizontally along the bottom of the chart, although you can modify the scale in the same way as you do with these other chart types.) Pie and donut charts don't show a value scale at all. Note: It's worth noting that quite a few unsavory individuals try to skew charts with crafty scale tricks. People often show two similar charts next to each other (for example, sales in 2006 and sales in 2008), and using a smaller scale in the second one to make it look like nothing's changed. Once you finish this section, you'll have a good idea how to spot these frauds. Some companies even have policies that enforce strict scale usage! To change the scale, right-click the value axis, and then choose Format Axis. Or, if you find it hard to select the part of the chart you want, choose the value axis from the list in the ribbon's Chart Tools Format When the Format Axis dialog box appears, choose the Axis Options section (shown in Figure 18-21). You have the choice of letting Excel automatically set the scale based on your data, entering the values you think are appropriate.

Note: When you set a scale value to Auto, Excel calculates it based on the current chart size and your current data. If you add more data, change the data values, or resize the chart (in which case there's more room to show intermediate values on the axis), Excel may modify the scale. But when you use Fixed, your numbers are hard-wired into the chart, and Excel never changes them (although you may, later). Several settings determine the scale of your chart. These settings include:

Note: When you first create a standard chart, minor tick marks are turned off, so the minor unit setting doesn't have any effect. To set whether Excel shows major and minor tick marks, choose an option from the "Major tick mark type" and "Minor tick mark type" lists. Anything other than None does the trick. (The various options just determine exactly what the tick marks look likefor example, whether they're on the inside of the grid, the outside, or if they cross completely.) Along with the settings just listed, you may also want to tweak the "Horizontal axis crosses" setting at the bottom of the dialog box. This number controls where the category axis line crosses the value axis. Usually, this line's right at the bottom of the chart, at the minimum value. However, you have two other choices. You can choose "Maximum axis value" to place the category axis at the top of the chart. The scale remains the same (meaning the minimum value's still at the bottom of the chart and the maximum value's at the top). More interestingly, you can choose "Axis value", and then type in the exact value where the category axis should appear. This choice lets you put the axis somewhere in the middle of your chart. For example, you may want to plot a chart of test scores and draw the axis at a point that would indicate the minimum passing mark. Note that in a column chart, when a column has a value that's less than the axis, it points "downward," as you can see in Figure 18-22 (bottom). Using these basic ingredients , you have a good deal of control over your chart's appearance. Figure 18-22 compares a few different options that demonstrate how different scale choices can transform a chart, with the help of a little formatting.

The Format Axis dialog box also provides a few specialized options that aren't as commonly used but are still quite interesting. They include:

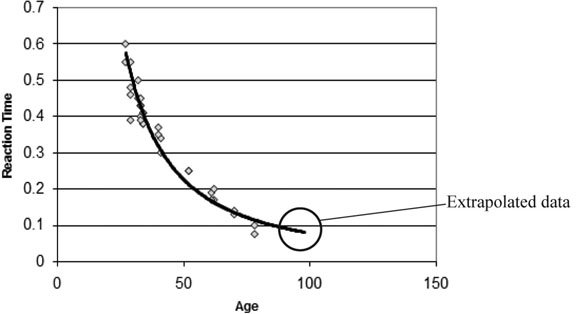

Note: If you're using a numeric or date-based category axis, you can format the scale of the category axis in the same way you format the scale of the value axis. You may want this option when you're creating an XY scatter chart or a line chart. If your category axis just displays labels, you can still format it, but you have fewer options. You can't change the scale, but you can reverse the order of categories, add tick marks, hide labels, and format the axis line's look. 18.5.2. Adding a TrendlineOne of the main reasons that people create charts is to reveal patterns that are hidden in the data. A gift card company may look at a historical record of sales to make an educated guess about the upcoming holiday season . Or a researcher might look at a set of scientific data to find out if potatoes really can cure the common cold. In both these examples, what's most important is spotting the trends that lurk inside most data collections. One of the easiest ways to spot a trend is to add a trendline to your chart. A trendline's similar to an ordinary line in a line chart that connects all the data points in a series. The difference is that a trendline assumes the data isn't distributed in a perfectly uniform pattern. Instead of exactly connecting every point in a series, a trendline shows a line that best represents all the data on the graph, which means that minor exceptions, experimental error, and ordinary variances don't distract Excel from finding the overall pattern. Figure 18-23 shows an example.

The other important point about trendlines is that they can predict values you don't have. The gift card company can use a trendline to get a good estimate of future sales, while a scientific experimenter can make educated guesses about data that wasn't recorded. People most often use trendlines in XY scatter charts. Trendlines also makes sense in a column chart, and they can work in line, bar, and area charts in specialized circumstances. To add a trendline, follow these steps:

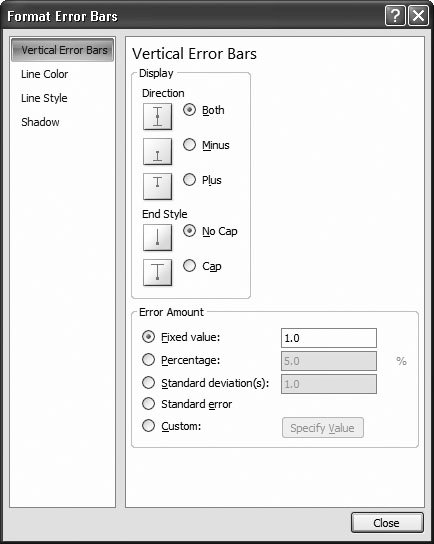

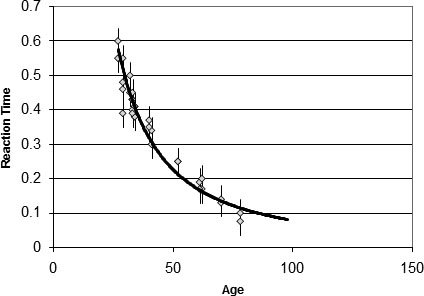

A standard trendline fits the data you have. However, you can also extend a trendline forward or backward to fill in values you don't know. This process of estimating data that you don't have (based on data that you do have) is extrapolation . A closely related concept is interpolation , which estimates unknown data values between known existing values. If a gift card company has information about sales from 2003 to 2006, you'd use extrapolation to predict sales in 2007. To make an educated guess at what sales were like in March 2004 (a month in which your firm lost its sales data), you'd use interpolation. All trendlines necessarily use interpolation since there's always, in effect, "missing" data points between the data points you're providing. To extrapolate values in a trend, choose Chart Tools Layout Note: Don't always trust trendlines. It's quite possible that a relationship holds true only over a limited set of values. If you use a rising sales trendline as the basis for guessing future results, Excel's guesses don't, of course, take into account unexpected developments, like limited inventory or rising production costs. Similarly, if you extend the age versus reaction time comparison in Figure 18-23 too far, you'll wind up with ages and values that don't make sense (like a reaction time of 0 seconds, or a reaction time for a 300-year-old). 18.5.3. Adding Error Bars to Scientific DataIn a typical scientific experiment, you have two important sets of information: the actual results and an estimate that indicates how reliable these results are. This "reliability" number is the uncertainty . The uncertainty doesn't compensate for human error, faulty equipment, or invalid assumptions. Instead, it accounts for the limited accuracy of measurements. Think of the typical bathroom scale, which can give you your weight only to the nearest pound . That means there's an uncertainty of 0.5 pounds because any given measurement could be off by that amount. If a scientific experimenter weighs in at 150 pounds, he would record that measurement as 150 ±0.5 (150 pounds plus or minus 0.5 pounds ). Any other calculations based on weight need to take this potential inaccuracy into account. Because every type of measurement has a different range of accuracy, there's always a certain degree of imprecision that you need to watch out for before you make a dramatic conclusion. In a scientific chart, you can indicate the uncertainty using error bars, as in Figure 18-25. If you plot 150 ±0.5 on a chart, you should end up with a point at 150 and an error bar that stretches from the point up to 150.5 and down to 149.5. To add scientific error bars to a chart, follow these steps:

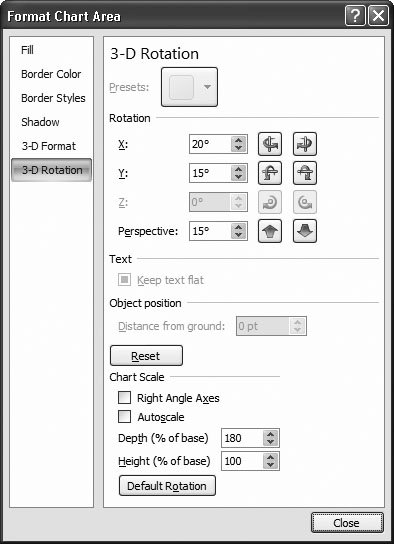

18.5.4. Formatting 3-D ChartsAs you learned in Chapter 17, many charts provide subtypes that are drawn in three dimensions. Some 3-D chart types are no different than their plainer 2-D relatives. In these charts, a 3-D effect simply gives the chart a more interesting appearance. But in true 3-D charts, it adds information by layering data from the front of the chart to the back, with each series appearing behind the other. (The column chart has seven subtypes . The first three are ordinary 2-D charts, the second three use a 3-D effect, and the last one's the only true 3-D chart. For more details about what subtype each chart supports, see the section "Chart Types" in Section 17.4.1.) In true 3-D charts, you may need to take special care to make sure that data in the background doesn't become obstructed. A few tricks can help, such as reordering the series and simplifying the chart so it isn't cluttered with extraneous data. You may also want to rotate or tilt the chart so that you have a different vantage point on the data. To rotate or tilt a chart, follow these steps:

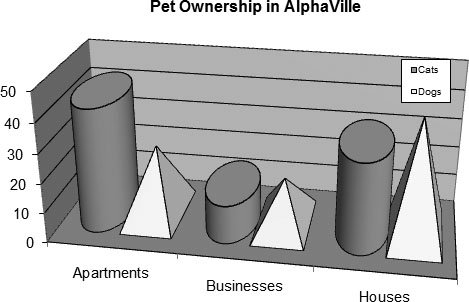

18.5.5. Changing the Shape of a 3-D ColumnExcel provides several subtypes of column and bar charts that use a 3-D effect. Excel also provides the Cylinder, Cone, and Pyramid chart types, which are always three-dimensional (see the description of chart types, beginning in Section 17.4.1, for more information). It doesn't really make much difference whether you use columns, pyramids , or conesthe overall effect is pretty much the same. However, you create a much more dramatic effect by putting more than one shape in a single chart. If you want to compare two series, then you could represent one with columns and the other with cones, as shown in Figure 18-27.

To try this out, follow these steps:

|

Current Selection section. Then, choose Chart Tools Format

Current Selection section. Then, choose Chart Tools Format