Computerized Tomography

Authors: Flaherty, Alice W.; Rost, Natalia S.

Title: Massachusetts General Hospital Handbook of Neurology, The, 2nd Edition

Copyright 2007 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

> Table of Contents > Imaging > Computerized Tomography (CT)

Computerized Tomography (CT)

A. Indications for noncontrast study

Stat scan for ICH, acute stroke, or altered consciousness after neurosurgery. Good for hydrocephalus, brain edema, skull fractures, intracranial air, calcifications, metal in head. Adequate for acute or unstable pt. who cannot have MRI.

B. Indications for contrast

( Contrast head CT is not a CT angiogram.) Any process with disrupted blood-brain barrier (e.g., tumor, inflammation, subacute stroke, longstanding hypertensive encephalopathy, etc.).

C. Indications for CT myelogram

Spinal cord lesion in pt. with multiple back surgeries, metal implants causing artifact, or who cannot get an MRI. Does not show lateral or foraminal herniations.

D. Indications for CT angiogram

CTA shows anatomy better; time-of-flight MRA shows blood flow more accurately. Stroke assessment before thrombolysis, neck vessel dissection, aortic arch or vessel origin stenoses. Arterial lesion in pt. who cannot get an MRA.

E. What CT is bad for

Posterior fossa and brainstem (much artifact), small lesions, subacute blood (isodense with brain).

F. Relative contraindications

Noncontrast: Limit use in first trimester of pregnancy. Unstable pts. should not be sent to the scanner unmonitored.

Contrast: Renal failure; creatinine should be <2.0; repeat contrast only after 24 h. Previous contrast reaction. Contrast can sometimes trigger flash pulmonary edema. See Allergy, p. 191, for prevention and rx of contrast allergies.

G. CT lesions by degree of hyperdensity

Bone > clotted blood > liquid blood > subacute (~2 wk) blood [all equal to] brain tissue > CSF > water > fat.

P.180

See also: DDx by MRI appearance, p. 183, for the DDx of ring-enhancing lesions, etc.

Hyperdense (bright) lesions: Recent blood, metastases (often), meningioma, calcification, bone.

Calcifications: Seen in oligodendroglioma, toxoplasmosis, neurocysticercosis, meningioma, Fahr's syndrome, AVM, calcified aneurysms, old infections. Normal in choroid plexus, pineal.

Hypodense (dark) lesions: Infarct 3-12 h, brain tumors, inflammation, old blood, edema, posttraumatic changes, fat, cysts, air.

Ventriculomegaly: Obstruction, atrophy, NPH.

H. CT of specific lesions

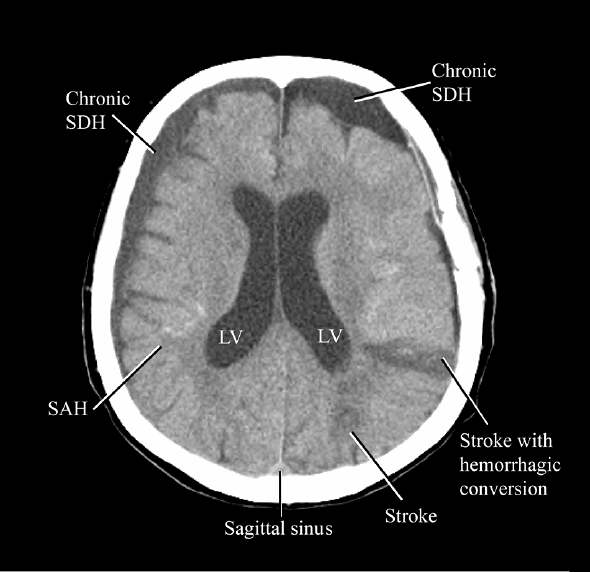

Infarct:

Acute: Infarcts are often hard to see for 12-24 h. Large strokes may show early loss of gray-white differentiation, sulcal definition, and even hypodensity as early as 3 h after sx onset.

Subacute: Hypodensity in the distribution of a defined vascular territory, both grey and white matter involved. Look for edema, mass effect, or hemorrhagic conversion. Some tiny lacunar strokes may never be visible by CT. Strokes 2-4 wk old may have ring enhancement with contrast.

Chronic: Hypodensity, often with encephalomalacia (tissue loss) that may cause sulcal or ventricular widening.

Figure 23. CT appearance of infarcts, SDH, and SAH.

CT signs of intracranial hemorrhage: See also Intracranial Hemorrhage, p. 61.

Epidural hematoma: High-density biconvex (lens-shaped) area next to skull. Does not cross sutures. Often with skull fracture.

Subdural hematoma (SDH): High-density, crescentic area next to skull. Crosses sutures but not the midline. Look for edema, shift, cortical flattening, associated fracture or scalp bruise. Subacute SDH may be isodense; see only obliteration of sulci and midline shift. There may be no shift if SDH is bilateral.

Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH): Serpentine density in sulci, fissures, and basal cisterns, often dissecting into ventricles. Look for associated fracture or scalp bruise, hydrocephalus, hematoma that may need evacuation. Often bleed location predicts aneurysm location. If suspicion of SAH but negative CT, do LP.

Intracerebral hemorrhage: Blood within brain parenchyma. Often surrounded by edema. Location is guide to cause.

Hypertensive bleed: Usually in basal ganglia, thalamus, brainstem, cerebellum, or white matter. Often there is intraventricular blood.

Amyloid bleed: Usually at gray-white junction (lobar), may have subarachnoid component. Get an MRI with iron susceptibility sequence to see additional occult lesions (microhemorrhages) that help confirm the diagnosis.

P.181

Contusion: Petechial hyperdensity associated with hypodensity, skull fracture or scalp bruise at the site of the blow (the coup ). Often there is a contrecoup injury in the opposite lobe.

Intracranial pressure: The absence of the fourth ventricle is a neurological emergency. It should be visible even if there is much artifact. Look also for sulcal effacement, midline shift, distortion of nearby structures by mass, effacement of cisterns.

Herniation: Includes:

Subfalcine herniation: Cingulate gyrus is displaced across the midline under the falx. May have enlargement of contralateral ventricle or ACA territory infarct.

Central transtentorial herniation: Obliteration of the perimesencephalic and quadrigeminal cisterns, sometimes with PCA territory infarcts and small Duret hemorrhages in the brainstem.

Uncal transtentorial herniation:

Early: Loss of the suprasellar cistern's normal smiley face (see Ventricles and cisterns, p. 178).

Mid: Brainstem displacement, compression of contralateral cerebral peduncle, sometimes contralateral hydrocephalus.

Late: Loss of parasellar and interpeduncular cisterns.

Tonsillar herniation: Cerebellar tonsils bulge down into foramen magnum. Best seen sagittally. They should be <5 mm below occipital-clival line.

Upward cerebellar herniation: Vermis is above tentorium; may compress cistern and aqueduct, and cause hydrocephalus.

Hydrocephalus: Frontal horns and third ventricles balloon ( Mickey Mouse ventricles), periventricular low density from transependymal absorption of CSF. In children, plain skull films may show splayed sutures.

P.182

Obstructive hydrocephalus: Large lateral ventricles with effacement of sulci. Third or fourth ventricle may look closed. There is usually a visible compressing lesion.

Communicating hydrocephalus: All ventricles and the cerebral aqueduct should be large. In hydrocephalus from atrophy, sulci are widened; whereas in hydrocephalus from CSF malabsorption (e.g., after SAH), they may be narrowed.

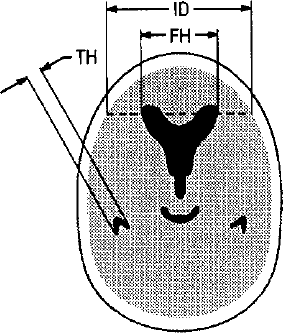

Ratios that suggest hydrocephalus: TH 2 mm for both temporal horns (see Figure 24) and either:

Sulci and fissures are invisible, or

FH/ID >0.5: where FH = largest width of frontal horns and ID = internal diameter of brain at this level.

Chronic hydrocephalus: Erosion of the sella turcica with 3rd ventricle herniating downward. Atrophy of corpus callosum on sagittal MRI. In children, macrocephaly.

Figure 24. Ventricular parameters in hydrocephalus. (From Greenberg MS. Handbook of Neurosurgery. 3rd ed. Lakeland, FL: Greenberg Graphics, 1994:224, with permission.)

Trauma:

Contusion: Predominantly gray matter hypodensity. See intraparenchymal blood, usually with little mass effect, usually in poles of cerebral hemisphere, next to bone.

Diffuse axonal injury: AKA shear injury. Seen especially after deceleration injury. Little change in CT. In severe cases, may see petechial hemorrhages in white matter and brainstem and diffuse cerebral edema. Best seen on MRI.

Skull fracture: May be complicated by epidural hemorrhage or CSF leak. Fluid in a sinus or mastoid suggests an occult fracture. May take several days to become visible.

Tumor: CT is sensitive enough for most cortical tumors that are large enough to be symptomatic. Small metastases, posterior fossa tumors, and some isodense gliomas will require contrast or MRI.

Mass: With contrast, most tumors are bright or ring enhancing. Without contrast, they may be dark or isodense, sometimes seen only by distortion of adjacent structures. Look for L-R asymmetries.

Associated findings: Look for dark edema surrounding the tissue, midline shift, hydrocephalus, herniation, blood, infarcts.

In infants, because there is no gray-white differentiation, it is easy to miss small amounts of edema.

DDx: Inflammation, enhancing subacute infarcts.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 109