Designing A Blueprint For A Knowledge-Centric Organisation

Most of us don’t have the luxury of designing an organisation from scratch, in the same way that we might design a green-field production site. But imagine for a moment that you had been given this task. How would you set about building an organisation that was perfect from a knowledge creation and sharing perspective? What would be the key components?

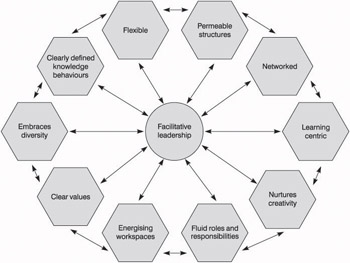

From my own research, combined with thoughts from other authors who have written about the cultural dimension of managing knowledge, it seems that there are a number of key elements as indicated in Figure 3.1.

Figure 3.1: Towards a blueprint for a knowledge-centric organisation

Clearly Defined Cultural Values

Ahmed, Kok and Loh (2002) have defined a number of cultural norms that they believe are essential for knowledge building and sharing. These include:

-

Challenge and belief in action

-

Freedom and risk-taking

-

Dynamism and future orientated

-

External orientation

-

Trust and openness

-

Debate and listening

-

Cross-functional interaction and freedom

-

Committed and involved leadership

My own research (Evans, 2000) identified the value base in knowledge-enabled organisations as:

-

Openness

-

Trust and integrity

-

Tolerance of failure

-

Respect for individual contributions

-

Generosity and reciprocity – knowledge sharing, not knowledge hoarding

-

Co-operation and collaboration

Trust has become a vital ingredient in the modern business world, particularly given the shift towards virtual organisations, organisations that do not physically exist but instead consist of a group of companies/people all working in an area of common interest.

One of the areas that organisations need to pay attention to is addressing the cultural paradoxes that occur in managing knowledge. Some of these paradoxes, as defined by Probst, Raub and Romhardt (2000), are shown in Table 3.2.

| We train our employees | . . . but | we do not let them use their knowledge |

| We learn mostly in projects | . . . but | we do not pass on our expertise |

| We have an expert for every question | . . . but | few people know how to locate him/her |

| We document everything thoroughly | . . . but | we cannot easily access our knowledge store |

| We recruit only the brightest | . . . but | after three years we lose them to our competitors |

| We know everything about our competitors | . . . but | not much about ourselves |

| We ask everyone to share their knowledge | . . . but | we keep our own secrets |

| We co-operate in order to learn from others | . . . but | we do not know what our learning goals are |

How many of these paradoxes exist within your organisation? What other paradoxes are you aware of?

What do you think HR’s role should be in addressing these?

Embraces Diversity

Perhaps one of the cultural values that should be added to the above lists is that of valuing difference, in whatever shape or form, e.g. background, perspectives, experience. An organisation that does not encourage and support diversity is one that is destined for extinction according to Eden Charles, a leading Diversity and Change consultant[1]. Diversity, he argues, is crucial for success in a business world that consists of diverse markets and diverse consumers. It is not nice to have, but it is a critical component of business success.

But what does your organisation understand by diversity? In many organisations the terms Equal Opportunities and Diversity are often used interchangeably and yet they are distinctly different. Equal Opportunities practices focus on addressing unfairness in the recruitment, selection and retention practices. They also tend to focus on targeting particular social groups for specialist attention.

An organisation that considers itself diverse, however, operates from a different standpoint and set of assumptions. Organisations that embrace diversity, so individual differences, in whatever shape or form, are valued for just that, their differences. Doing different things and doing things differently are acknowledged ways of producing new perspectives. Difference, according to Gryskiewicz (1999) a leading writer in the field of creativity, provides the all-important sense of turbulence, from which creativity flows. Diverse, but complementary skills, are also felt necessary to produce the friction that generates creative sparks.

Organisations that truly embrace diversity, according to Eden Charles, adopt the following principles:

-

Include a broad-range of people; no one is excluded

-

Individual differences are recognised

-

All employees are helped to maximize their potential and contribution to the organisation

-

Individuals are encouraged to free themselves up

-

Concentrate on the issue of movement of people

-

Believe that diversity is the concern of all employees, not just

HR practitioners

As HR practitioners this suggests a need to focus on practices that:

-

Enable differences to be recruited and retained

-

Encourages and draws out different ways of thinking

-

Appraises and rewards people for their ability to make a valued difference

-

Encourages different networks to thrive

-

Facilitates the practice of helping teams get to know each other’s differences and challenges the assumption that this is not productive use of time

-

Fosters networking, to maximise exposure to differences

-

Acknowledges that individuals learn differently and provides a range of learning opportunities for them to draw on

-

Help teams to address collective needs as a prerequisite for working together, rather than just concentrating on getting things right with one or two members (Herriot and Pemberton, 1995)

-

Enable individuals to develop a diverse set of interests, thus maximising opportunities for diversity of knowledge and experience

From the organisation’s perspective a more diverse workforce provides a deeper pool of talented people that more closely reflects the pluralistic, multi-cultural client base of the 21st century business world (John Bank, 1999).

Nurtures Creativity

For knowledge to become the source of sustainable advantage organisations need to develop a culture where creativity is encouraged and supported. Creativity is vital for developing new knowledge assets e.g. new products, services, or processes, which sets the organisation apart from its competitors.

The term creativity, as with the term knowledge, is one that individuals and organisations have difficulty understanding. Theresa Amibile from Harvard Business School, one of the leading experts on creativity, defines it as ‘The production of novel and appropriate ideas by individuals or small groups[2].’ She defines innovation as ‘The successful implementation of creative ideas within an organisation.’

Amabile argues that the individual components of creativity are:

Expertise: knowledge about particular domain points; technical skills and talent in the domain.

Creativity skills: flexible cognitive approach; energetic persistent approach to work and an orientation to risk-taking.

Task motivation: motivated by a deep interest in the area and challenges presented by their work.

However, environmental factors play an influencing role in shaping creativity, for example the availability of resources, management practices, as well as the organisation’s motivation to innovate.

In his book Releasing Creativity, John Whatmore argues that creativity within organisations arises through the interaction between the task, the team and the organisation, with leadership being a vital enabler for connecting these three overlapping areas. His research identified some of the organisational disabling influencers for creativity as:

-

Too much focus on the task and/or the client and not enough on the process/people aspects

-

Too much control and bureaucracy

-

Hierarchical structures

-

Paternalistic culture

-

Boxed thinking

-

Unrealistic time constraints

-

Not users or nourishers of ideas

-

Lack of recognition that people have a variety of objectives

-

Low support for personal development

-

Physical spaces divisive

and in terms of the role of leaders, where leaders:

-

have less interest in the personal development of people in their team

-

have too high a workload to have enough time for team members

-

are not a ‘people person’

-

are not skilled in ‘process’ skills

-

only having partial responsibility for group activities e.g. selection of team members

-

do not give people the space to be creative themselves

Given the right conditions creativity will flourish. An important part of that is getting the right leadership in place. How can leaders make a difference? According to John Whatmore there are a number of factors to consider:

There are so many practical considerations: the task to fit each person in a way that will not wreck another person’s opportunities

and

Motivating inquisitiveness and encouraging self-exploration, and finding ways in which they can understand for themselves

and

By giving responsibility and guidance for them to learn for themselves, to learn by discovery, and then letting them have a go . . . giving them ‘the dignity of risk’.

How does this type of enabling leadership develop and who should be responsible for developing an organisation’s leadership? These are key questions that HR professionals, working in a strategic role, need to consider and ones that will be returned to in Chapter 5.

Permeable And Agile Structures

Charles Leadbeater argues that in knowledge businesses it is vital to have organisational structures that are adaptive and networked given that in the complex and ever-changing business world that we now live in no single company can develop the solutions needed to stay successful.

Many new consumer products today are developed through collaborative ventures between different strategic partners. A collaborative network according to Leadbeater ‘. . . should provide companies with distributed intelligence, sensing new opportunities, combining different skills and sharing ideas to create and exploit new knowledge’ (Leadbeater, 1999: 131).

It is not just in the private sector where partnership working is important, public sector companies too are being encouraged to work in partnership with a range of different stakeholders. However, in partnership arrangements the rules of the game are different. Managers can no longer rely on the authority that goes with their position to get things done. Instead they have to win the trust and respect of each of the partnering organisations, something that takes time to develop.

Working with more fluid and permeable structures requires a different mindset and management style. Traditional organisational forms and structures bring with them a sense of security for individuals – people know their place and what is expected of them. Managers too have a better sense of how to manage and indeed often feel more comfortable managing within traditional structures.

As Charles Handy (1996) points out there are important implications of working in virtual organisations. First, greater attention needs to be given to selecting the right people. This suggests a need to think about a different approach to recruitment, one that enables both parties to get a better feel for whether there is likely to be a ‘good fit’. Second, the size of an organisational unit will have implications for the level of trust. The bigger the unit the less chance there will be to really get to know colleagues and hence establish relationships of trust. Third, as vision and values will really count, time will need to be allocated to talking about these things. Fourth, as trust is fuelled by talk then communication, by a multitude of means, is crucial. In virtual organisations communication needs to be well managed, to avoid the situation of ‘out of sight, out of mind’. But if organisations want to survive then they will need to find ways of dealing with these crucial areas, rather than continuing to stick with what has worked in the past.

Flexible

Flexibility and agility have become two of the most coveted business competences in the last couple of decades. However, achieving flexibility is not a straightforward process. First organisations have to develop a shared understanding of what is meant by the term flexibility, then they have to review their practices to find out which ones get in the way of achieving flexibility.

The flexible firm needs to make creative use of each of the four flexibility categories:

Temporal flexibility – this relates to the time-span within which work is carried out. The options that come under this form of flexibility include: part-time working, short-term contracts, annualised hours, job-share, or V-time (where an individual reduces their hours to just below full-time on a temporary basis) and zerohours or bank (where individuals work for an organisation but do not have any guaranteed contracted hours), and associated schemes (which include individuals who offer specialist services to organisations on a short-term, project-by-project basis).

Locational flexibility – this relates to the physical location where work is carried out. This form of flexibility encompasses: teleworking, working at home, or a combination of working at home and at the office. Teleworking can enable individuals to benefit from temporal as well as locational flexibility, i.e. offering greater flexibility over the overall number of hours worked and also the time window within which work takes place. Research by Gartner[3], a leading technology research and advisory consultancy, identified that around 44 per cent of organisations plan to invest nearly half of their IT budget on systems to increase business agility, including putting the infrastructure in place to support mobile working.

Numerical flexibility – this relates to how organisations manage their overall resources in relation to the work that needs to be done. As part of an organisation’s overall resource strategy they may choose to sub-contract some of their services or indeed outsource complete functional areas. Contracting out work to selfemployed professionals would come under this category.

Functional flexibility – this relates to the way in which different services and/or skills are combined in order to provide a more responsive service to customers. Many customer service organisations, such as retail, financial service and hospitality, have sought to enhance their overall level of flexibility through the introduction of multi-skilling. Certainly, for individuals, this can be attractive since it enables them to develop a broader skills base, thus adding to their employability. In addition, where individuals get an opportunity to develop new skills by working in different functional areas, this provides them with an opportunity to develop their knowledge about the linkages between different functional areas. Armed with this knowledge employees can then engage in a dialogue about how to enhance these linkages and hence overall performance.

There is another form of flexibility that needs to underpin each of the above categories of flexibility – mindset flexibility. Mindset flexibility means being open to new ways of thinking about how work can be achieved and indeed how and where business should be conducted. This requires a time investment in order to gather intelligence (‘know of’) about the practices in place in other organisations. Another example of mindset flexibility is where individuals are able to adjust to leading on one project, and being a team member on another.

However, although the range of flexible employment options offered by employers has been on the increase since the mid-1980s, some individuals feel that organisations are still not flexible enough. This is one of the reasons that some professionals opt for self-employment (Evans, 2001).

The removal of layers of management does not necessarily make organisations more flexible and agile. Clearly removing unnecessary bureaucracy is important if organisations want to speed up the decision-making process. Customers do not want to have to wait weeks for decisions to be made/ratified by senior management or institutional committees. Sadly the introduction of flatter organisational structures has earned some organisations the reputation of being anorexic, i.e. suffering from corporate amnesia, from stripping out key knowledge assets without any regard to the longer term implications for the business. As a result these organisations now have less flexibility as they have less resource to draw on in order to take advantage of new business opportunities.

Fluid Roles And Responsibilities

Fluid role and responsibilities go hand-in-hand with looser organisational structures. Instead of having tightly defined job descriptions individuals will need to become more adept at working with fluid role descriptions. Like entrepreneurs, employees will need to become comfortable with wearing many hats, as well as developing the ability to wear multiple hats simultaneously.

Some of the new roles required to build and maintain a knowledge-centric organisation are discussed in the next chapter.

Learning Centric

The pace of change in businesses today makes it difficult to keep abreast of existing knowledge let alone identify what new knowledge will be needed in the future. One thing is certain as Arie de Geus, formally of Royal Dutch Shell, points out ‘ Learning faster than your competitor may be the only sustainable competitive advantage.’ Peter Senge, points out ‘ The need for understanding how organisations learn and accelerate that learning is greater today than ever before. The old days when a Henry Ford, Alfred Sloan or Tom Watson learned for the organisation are gone. In an increasingly dynamic, independent and unpredictable world, it is simply no longer possible for anyone to figure it all out at the top. The old model “the top thinks” and “the local acts” must now give way to the integrative thinking and acting at all levels.’ (Peter Senge, 1998: 586)

But what mindset shift would be needed for organisations to become learning-centric? What would it take for learning conversations to become as natural events in the workplace, as the conversations that individuals have about their favourite football team, or the TV programme that they watched the previous evening?

If only we could encourage individuals to be enthusiastic about dissecting practices/events in the workplace to tease out good practice and lessons learnt. Sadly individuals often get switched off learning, because of their earlier experiences of formal learning, i.e. at school or college.

One of the biggest challenges that learning institutions face is that of how to motivate individuals to engage with the process of learning, this can also be a challenge for organisations too. There are relatively few organisations that would class themselves as ‘learning organisations’.

Becoming a learning-centric organisation requires instilling behaviours whereby all individuals are prepared to question and challenge the routines that get in the way of effective and efficient practices. It also requires a shift in organisational thinking too, whereby time spent reviewing how things get done (i.e. process), is perceived as being as important as what gets done (i.e. outputs/deliverables). In today’s ever-changing business world organisations need to embrace second-order change (i.e. doing different things, not just doing existing things better); a process that is often best facilitated through collaborative working.

Equally, organisations need to be clear about the extent to which they are prepared to invest in building generic human capital (i.e. skills and knowledge which enhance employees’ productivity irrespective of where he or she is employed) and specific human capital (i.e. skills and knowledge which only apply to current employer). Chapter 6 discusses some of the issues relating to this strategic decision.

Clearly there are important leadership issue here since leaders (this includes HR) are the ones in a position to act as role models to others in the organisation, or at least give their stamp of approval for changes proposed by team members. By working in partnership with the line, HR can help the business review their business processes to tease out inefficiencies and make plans to address these.

One of the other lessons that learning organisations need to address is the importance of recognising when they don’t have all of the capabilities in-house to do what the business wants to do. Recognising and accepting this at least gives the organisation the opportunity to borrow, or learn, from the experience of others outside the organisation. This was the strategy adopted by Shell Oil as part of its transformation from traditional products to an operations focus (Gubman, 1998). This transformation involved the organisation concentrating on developing its organisational capabilities for finding, producing, transporting and marketing gasoline. As the organisation realised that it didn’t have the experience/capability to do the things that they wanted to do on their own, they decided to form a partnership arrangement with other organisations, such as Amoco. The key lesson that the organisation learnt from this experience is that of knowing when it is best to do things on your own, and when it is best to work in partnership with others.

Networked

Networking has been identified as a core competence in knowledge-based businesses (Bird, 1994; Davenport and Prusak, 1998). It is the means by which businesses acquire business critical knowledge. But as we have seen in the example above about Shell Oil, it is also the means by which businesses acquire and build effective strategic partnering arrangements, which either help fill a gap in existing knowledge, or complement existing knowledge.

Through networking organisations are able to build knowledge supply chains that extend outside of their own organisation, similar to physical distribution supply chains. Most service providers today have some form of partnering arrangements with other organisations to help them deliver their business.

The networks that businesses belong to will need to remain fluid, changing as and when the business changes. Individuals within organisations need to be networked too. As well as helping to build human capital, networking is important for building social capital (i.e. ‘the oil that lubricates the process of learning through interaction’ (Kilpatrick and Falk, 1998)).

Facilitative Leadership

Facilitative leadership is the heart of a knowledge-centric organisation. Without supportive leaders then creativity will not emerge and individuals will not be willing readily to share their knowledge. John Bank defines the characteristics of facilitative leadership as:

-

Having vision and values to support diversity.

-

Demonstrating ethical commitment to fairness.

-

Having a broad knowledge and awareness regarding primary and secondary dimensions of diversity and multi-cultural issues.

-

Being open to change based on diverse inputs and feedback about own personal filters and blind spots.

-

Mentoring and empowering diverse employees.

-

Acting as a catalyst for individual and organisational change.

Peter Senge suggests that in the global marketplace companies need to foster a new leadership model, one that is based on principles, particularly mutual trust[4]. Empowerment, according to Senge, does not work without trust. Trustworthiness comes from behaviours such as equity, justice, compassion, integrity and honesty. Trustworthiness will not evolve, according to Senge, in the old command and control management structures.

Other writers point out that in a knowledge-centric culture, one of the key roles for HR is to develop leaders who can nurture ‘pockets of good practice’ in which individuals are encouraged and enabled to identify and apply usable ideas for local and organisational wide benefit (Bailey and Clarke, 1999).

Physical Architecture To Support Collaborative Working And Learning

The physical work environment has certainly changed over the past twenty years. In the 1980s open-plan offices started to replace traditional office environments, particularly where organisations were located in out-of-town business parks. One of the design features of these open-plan buildings was to scatter coffee machines around each floor, making coffee more accessible; the aim being to demonstrate looking after the employees. However, one of the practices that emerged was that people took coffee back to their desks and continued working, rather than breaking for a coffee and a chat with colleagues.

In the 1990s there has been a trend towards more mobile working, with certain categories of employees only working in a central office environment on two or three days a week; the rest of the time being spent working on client sites, or working from home. Organisations realised that these large open-plan offices were being under-utilised and the accountants were quick to work out the cost of this under-utilisation. The result – the introduction of hot-desking, where individuals no longer have their own personal workspace, but instead book a shared workspace as and when they plan to be in the office.

Richard Scase points out ‘If, in the past, the workplace was the place where work was done, in the information economy it is the place where ideas are exchanged and problems solved. This means that the architecture and the design of the workplace needs to encourage employee sociability’ (Scase, 2002:87)

Scase suggests that the physical architecture of the future workplace will consist of: large reception area; ‘public space’ for meetings with colleagues and customers; hot-desking area; project rooms and confidentiality suites for private meetings.

There are signs that organisations are already re-designing their office environments with some of these considerations in mind. Despite the trend towards more mobile working many organisations are beginning to see the importance of investing in the right physical environment to encourage knowledge building and sharing. There seems to be a growing acceptance of the critical importance, from a knowledge management perspective, of bringing teams together, particularly those who are geographically dispersed or working in virtual teams. The view is that it is in these shared spaces – physical, mental and virtual – knowledge flows. Some examples of changing practice, in line with Scase’s thinking about the future workplace, include:

Jones Lang Lasalle, a global provider of real estate and investment management services, has set up break-out spaces on two of its floors in its Head Office. These areas form part of the central areas, located close to the lifts and main thoroughfares, thus making them easily accessible. Each of these break-out areas contain coffee machines, PCs and plasma screens for presentations. These breakout areas can be used for formal meetings, presentations, as well as informal meeting spaces.

The European headquarters of Electronic Arts, the world’s largest interactive entertainment software company, was designed to provide a campus atmosphere. A key feature of the building is a fully glazed open street overlooking a lakeside setting.

This area is used to hold impromptu meetings over a coffee, or to test latest releases of games at one of the games platforms. This new head office environment was designed with people firmly in mind. It has a self-service cafeteria, a fully equipped gym, a general store, a library, a sports bar and a floodlit outdoor sports court.

IBM UK – as more and more people within the organisation now work more flexibly this has created an opportunity for the organisation to consider rationalising its office space, or at least transform its usage. Personal desks at IBM’s UK head office are gradually being transformed into mobile workstations, which individuals connect to as and when they require. As traditional office space becomes free, this has created an opportunity for the organisation to build in more coffee lounges and informal meeting areas, creating more spaces for individuals to hold informal meetings.

GlaxoSmithKline’s new head office has a river running alongside the building’s central avenue, which is filled with shops and cafes for staff to meet socially.

However, one of the dilemmas that many organisations face is that of reducing costly overheads, such as the cost of central office space. As organisations grow in size they often look for ways of using existing office space more efficiently rather than having to engage in expensive building work. Several of the organisations that I made contact with as part of the background research for this book have experienced a dilemma regarding the space allocated to central restaurant facilities. Each of them had deliberated over whether to remove their restaurant facilities, thus freeing up space to allocate to offices. While financially this decision seemed to make sense, on reflection many felt that this would have drawbacks from a knowledge management perspective. Organisations that have removed central restaurant areas, replacing them with coffee machines and food dispensers, have found that this is not conducive to encouraging informal networking. With nowhere to sit to drink their coffee individuals have no choice but to take this back to their desks – from a knowledge management perspective this is a lost opportunity.

Clearly Defined Knowledge Behaviours

A summit of Chief Knowledge Officers, organised by TPFL[5], identified the core competencies for working in a knowledge culture as:

-

Curiosity and learning ability

-

Demonstrates initiative

-

Have a collaborative and team playing attitude

-

The capacity to make intellectual connections

-

Humility

-

The ability to focus on outcomes

-

Ability and willingness to share and receive knowledge

-

ICT literate – able to use the information and communication tools available

-

An appreciation of information management techniques – the ability to be able to locate and use information is felt to be a core competency for everyone in organisations, not just those working in specialist roles.

My own previous research identified several behavioural characteristics associated with knowledge workers (Evans, 2000), these include:

-

Having a holistic view of self and the broader world within which they operate

-

A strong sense of purpose, i.e. an understanding of why what they are doing is important

-

A passion for what they do and create

-

Demonstrate a strong sense of self, i.e. awareness of the impact of own actions on others

-

Show respect for other people’s views, ideas and opinions

-

Demonstrate a willingness to work collaboratively, i.e. to be open with others and trust others to be the same

-

Have a sense of generosity, i.e. willingness to make time to exchange ideas with others

-

Demonstrate a tolerance for uncertainty and risk-taking

-

Networked – able to build connections, inside and outside the organisation, as well as participate in communities of interest.

Enablers of these critical behaviours include:

-

Communication – need to develop a common language base so that everyone can engage in knowledge-building dialogues.

-

Equitable rewards – common performance criteria that everyone has access to; framework for career development, together with appropriate support; an opportunity to gain equity in the organisation through some form of share scheme.

-

Networking forums – both face-to-face and on-line.

-

Trust – indicators to consider to ensure that sharing is taking place include: response times for information requests by colleagues being satisfied; awareness of different roles individuals play so they can help to connect others as quickly as possible.

[1]E. Charles. Diversity: A draft Laurel Trends Paper. 2002. Further details about this practitioner’s work can be obtained from Info@EdenCharlesAssociates.co.uk

[2]T. Amabile. The Work Environment for Creativity. Oxford Forum for Assessment & Development, 2001.

[3]An Agile Age. A study by Gartner and reported in Computing, 18 July 2002.

[4]Masters of the Universe. Global HR, 01 October 2001. www.personneltoday.com

[5]S. Ward. Mobilising Knowledge: Skills for working in knowledge environments. www.TFPL.com

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 175