MP 2: Measure Potential

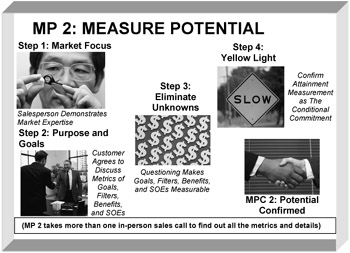

MP 2: Measure Potential has four steps. You use these steps to help customers gather specifics about their goals and filters. You both perform a test of reasonableness to see if customers first, you second, can achieve their goals.

If customers have multiple goals, rank them. Their goals are not equal in importance or value; the top one counts most. The secondary goals are typically luxury items rather than necessities. If customers have two or three number one goals, it is a sign that they have not yet assigned value to achieving them. When you make their goals measurable, they choose the one that produces the most value.

Prioritizing their goals helps you to understand why they ranked them as they did. Often, numerous filters surface when you ask customers to explain why they chose a goal as the most important one to achieve. Use their top-ranked goal to uncover their filters. You will find that the influencers (goal motivation, current, situation, plans, alternatives, and past keys) will change, but the prerequisites (decision maker, dates, funding, and attainment measurement) will not. The attainment measurement of the top-ranked goal sets the purchasing requirements your products must meet.

You also have a tough choice to make if your products cannot achieve their primary goals. You can focus on their secondary ones if you think you can show them that they can produce as much or more value than their primary one. The difference between the measurable benefits of the primary and secondary goals will determine the outcome. The tough choice is whether this uphill battle is worth the effort.

| Note | Customer etiquette dictates that you fulfill customers' expectations of a meeting—even if it means mentioning specific products in MP 1: Spark Interest and MP 2: Measure Potential. Therefore, make sure customers understand that the purpose of the meeting during MP 2: Measure Potential is to better understand what is involved in achieving their goals (measurable benefits, filters, and systems of evaluation). Be patient, customers expect product presentation at the first in-person sales calls. Keep reminding them and receiving agreement that it is their goals that will determine their product selections rather than the other way around. |

Yet, one glaring exception exists when it might be necessary to describe specific products during MP 1: if it becomes the only way to spark interest. With technically advanced or unique products, customers might not have any reference points to relate to them. A description, sample, or demonstration might be the only way for them to realize that previously unattainable goals are achievable. However, make sure when you meet during MP 2 that you shift the focus from the product's features to the goals it can help the customer achieve. (See Exhibit 6-5.)

Exhibit 6-5: MP 2— Measure Potential.

In addition, customers usually do not have all the details about goals, measurable benefits, filters, and SOEs at their fingertips. They need time to research information as do you. Typically, MP 2 takes at least two in-person sales calls to gather all the specifics and to find out any information you forgot to ask. However, this additional investment in the details shortens your sales cycle, not increases it. You and the customer only gather data that will decide if you can help them to achieve their goals. You then can make advance-or-abandon decisions sooner to prevent wasted efforts.

Step One: Market Focus

Display your knowledge of the customer's market segments by citing relevant facts. Technical statements about your features and benefits do not demonstrate expertise; your questions about their goals and filters do. Therefore, do not mention specific products during this phase either.

| Note | Ask the customer if anyone else will be at your in-person meeting. If there are other people attending, ask for their titles and their fields of interest. Be prepared to discuss goals that are relevant to their positions and/or fields of interest. |

Steven Smartsell mentions how long FutureTech in general—and he, specifically—has worked with computer manufacturers like Positron. He stresses how he is familiar with the issues that confront highly competitive industries like hers—such as fluctuating demand, high-dollar downtime for interrupted production, short product life, reliance on fewer suppliers, and constant manufacturing changes to accommodate new technological advances.

Step Two: Purpose and Goals

Start with dialogue questions to build rapport. Using customers' cues, be ready to shift into business gear. You achieve your first yes of the day when the customer agrees the meeting's purpose is to determine the potential of achieving her goals and your ability to help accomplish them. You then verify her stated goal(s). If you did not set a specific meeting purpose in MP 1: Spark Interest, ask customers, "What would you like to accomplish today that would make you feel that our time together was productive?'' Once you acknowledge their purpose, then share with them what you would like to accomplish to make it productive. Remember, it's your business time also.

Steven Smartsell confirms that the meeting's purpose is to get a better understanding of Olivia's stated goal of reducing downtime and whether FutureTech can help in this endeavor. He also verifies that Olivia has no other goals she wants to pursue at this time.

Olivia asks Steven to review with her some of his products and services that he thinks might be helpful to her operations. Steven tells her that while he has some general thoughts on what products might apply in her situation, he would not venture a guess until he understands her goals and purchasing considerations (filters) better. He will leave her some case studies of how FutureTech has helped other customers in her industry achieve goals such as reducing downtime or improving efficiency. He also offers to leave a general product and service catalog when their meeting concludes.

How to Handle the "Tell Me About Your Products'' Request

As previously discussed, customers often want you to describe your products before you ask them any questions. Customers feel that you only ask questions to posture your products as the right solutions for them—regardless of whether you know their goals or not. Therefore, they figure that they might as well ask you to become a "feature creature.'' When you finish your pitch, they will then let you know whether they are interested. Unfortunately, customer "interest'' without defined goals can lead to unfulfilled expectations and disappointments for all involved.

The following is a more-detailed example (with strategies and tactics in italics) on how to handle a product pitch request at the start of either MP 1 or 2.

Example

-

Customer: Tell me about your products and services.

-

Salesperson: Nothing would make me happier than having the opportunity to talk to you about my products and services. However, I wouldn't know where to start without first understanding what you want to achieve.

I thought our objective today was to better understand your priorities and what it would take you to achieve them. Once I fully understood your parameters (goals, measurable benefits, SOEs, and filters), I'll take your information back to my team. Then, after careful analysis of the specifics of your situation, we'll see if we can custom-tailor a program (Connecting Value sheet, Chapter 7) that achieves your goals.

I promise that I'll send you a summary of our findings for your review (see Scope of Work in Chapter 7). How does this plan sound to you (verifies agreement)? Finally, I'm confident that you'll find out more about what we do by the questions I ask you about your company than any product presentation I could make (positioning himself as a customer expert).

Step Three: Eliminate Unknowns

Start making customers' goals measurable by making their benefits measurable. Build their safety zones as large as possible. The more measurable the goals, the larger are the safety zones. You then qualify, clarify, and verify each filter in terms of how it affects the customers' ability to achieve their goals.

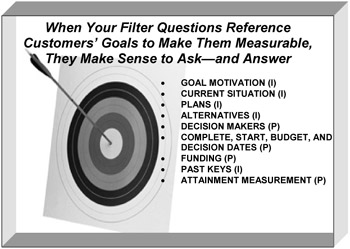

When you connect customers' filters to their goals, and not to your products, they do not feel manipulated by the questions you ask. For instance, think of how you would feel if a computer sales-person, who did not know your goals, asked you, "How much money have you set aside to buy a new server?'' Compare that question to this one from a computer salesperson who knows your measurable goal: "How much have you budgeted to reduce your system maintenance costs by $35,000 annually?'' (See Exhibit 6-6.)

Exhibit 6-6: Your questions should reference customers' goals.

Customers appreciate how your questions help them to make better purchasing decisions. When you deal with measurable goals and the specifics of filters, the room for unmet expectations decreases dramatically. You also create an environment where it does not feel like you are grilling them with rapid-fire yes-or-no questions.

Reinforce to customers the concept that details of measurable benefits, filters, and systems of evaluation determine whether you can achieve their goals. They are offering you challenges that become more formidable as they disclose more filters. Readily accept these challenges. The requirements for achieving their goals become more difficult not only for you but also for competitors as well. Again, if you chose your market segment correctly, these requirements help you to provide more value than do competitors. You are building your case to receive fair compensation for the unique or measurably better value your products provide.

| Note | If you cannot achieve a customer's goal or satisfy the attainment measurement, the details enable you to explain why. You can tell the customer what goals you can achieve and why. You might need to forgo this sales opportunity but not the prospects for future business. |

Although it is not the desired outcome, it beats wasting everyone's time, energy, and resources for one to three months. Typically, customers take this long to inform you that it does not make sense to do business with you. Ironically, positive customers who do not want to hurt your feelings might take longer, while negative customers usually require less time. They cannot wait to tell you why they are happy with their existing suppliers. Use the create-and-wait strategy in their case.

In Step Three: Eliminate Unknowns, Steven uses his active listening and questioning skills to quantify and obtain details about Olivia's goal (reducing downtime) and her filters. Pay special attention to how Steven will link each of her responses to his next question concerning that filter or the next appropriate filter. Clarifying points and comments are in parentheses and italics. While her answers could probably take you to two or three different filters, the case study will follow them in the order prescribed in Exhibit 6-6.

Steven uses the vague-clearer-measurable questioning pattern to quantify Olivia's answers. His qualifying, clarifying, and verifying questions will be his tools to find out both Column 1 and Column 2 details. In real life, various filters can surface at the same time and one question often prompts the customer to provide measurable answers. For illustrative purposes, each filter will surface one at a time and require Steve to ask versions of the following three questions for most of the filters to get to measurable:

-

What does that involve?

-

How does that affect you?

-

How much does that cost? or What are those details?

Steven also receives all the details of the nine filters on this first call. Typically, salespeople need more than one meeting to find them out. They figure out which details they missed when they fill out their Quick-Entry Sales Management (Q) sheets. They then call to find them out or schedule another meeting to do so. Remember to make it a two-way street. If you want new information, you must give out new information.

In addition, when reading this section, ask yourself, "Where do you stop with your questions?'' Do not stop until the answer to this question is when you receive measurable or detailed information. You and customers will reap the rewards as a result.

Continuing from Step 2: Purpose and Goals:

-

Steven: Olivia, what does reducing downtime mean to you? (Steven seeks to quantify her vague goal.)

-

Olivia: Our goal is to get our downtime reduced to no more than nine hours annually. (Olivia provides a clearer answer.)

-

Steven: What has prompted you to select that target figure at this time? (He wants to understand the filter of goal motivation—and why nine hours.)

-

Olivia: No matter what we do to address downtime, we still average about eighteen hours of production loss yearly. (Olivia explains her negative motivation and provides an answer that still needs to be converted to dollars.)

-

Steven: What does that end up costing you? (He seeks to quantify the dollar amount of downtime.)

-

Olivia: It costs us about $40,000 per hour of downtime. (Olivia provides a measurable answer and her SOE—dollar per downtime.)

-

Steven: So, you have been averaging about $360,000 of downtime annually? (He turns an hourly figure into an annual dollar total.)

-

Olivia: You got it. (Steven uses his next question to link her measurable response to the filter of current situation.)

-

Steven: What are you currently doing to reduce these costs?

-

Olivia: We have increased our monitoring of the equipment. (Olivia provides a vague answer.)

-

Steven: What does that involve?

-

Olivia: We dedicate two people per shift to constantly inspect the equipment for any warning signs. (Olivia provides a clearer answer.)

-

Steven: It sounds expensive. What do they cost?

-

Olivia: Each person costs about $40,000 annually; and with two shifts, that's a lot of money.

-

Steven: In other words, these four people add $160,000 to your production costs? (Steven always wants to get to the total dollar amount.)

-

Olivia: Hey, you seem pretty good with numbers. Yeah, $160,000 sounds about right. (Olivia provides a measurable answer. Steven uses his next question to link her measurable response to the filter of plans.)

-

Steven: So, what are you planning to do to get to those nine hours?

-

Olivia: We are looking at installing redundant equipment. (Olivia provides a vague answer.)

-

Steven: How many pieces of equipment will you need to buy?

-

Olivia: We are looking at purchasing three new pieces of production equipment. (Olivia provides a clearer answer.)

-

Steven: What will something like that cost?

-

Olivia: It could end up costing us almost $600,000. (Olivia provides a measurable answer. Steven uses his next question to link her measurable response to the filter of alternatives, which might include other suppliers.)

-

Steven: Besides purchasing new equipment, what other options are you looking at to reduce downtime?

-

Olivia: We might buy used equipment, which would cut our costs in half, although we might be risking reliability. Also, we have received presentations from PricePoint Services and FastShip Technology (Steven's competitors) about their predictive maintenance services and production equipment. For what it's worth, you are definitely making me think a lot more about my situation than they did.

-

Steven: Thanks. I hope you feel the information we are discussing will make it clearer what you want to accomplish and what it will take for a company to help you. (Steven does not take the bait and go into a product pitch or fall for the "What do they do for you?'' trap. He knows his competitors' strengths and weaknesses from his Competitor Product Profile sheets. Once he finds out Olivia's goals and filters, he will then know how to connect his products to them, and not have his solutions compared with his competitors' products. Let them compare their features to his features, and leave out Olivia's goals. In addition, he knows if he helps Olivia to define her purchasing requirements, she will view him more as an industry expert than his competitors.)

-

Olivia: I will let you know when I don't think it's making things clearer.

(Steven uses his next question to link Olivia's previous measurable response [half the costs of new equipment or $300,000, and knowing his competitors' price ranges] to the filter of final decision maker [FDM].)

-

Steven: Fair enough. When you are evaluating these different options, who will be involved with approving these types of decisions?

-

Olivia: I'll make the initial recommendation to my boss, Ronald Reuters, the CEO of the company.

-

Steven: What will he do with your recommendation?

-

Olivia: I have final approval if it achieves our goals and stays within budget; otherwise, he needs to get corporate approval. (Steven uses his next question to link Olivia's detailed response to the filter of dates [he could have also linked it to budgets].)

-

Steven: Upon approval, when would you and Mr. Reuters want to start?

-

Olivia: When the new budget goes into effect on October 15.

-

Steven: With that budget date, when do you want to make your decision, and then begin and finish the project?

-

Olivia: Make our decision by August 1, begin the project no later than November 1, and complete by fourth quarter. (Steven uses his next question to link Olivia's detailed response to the filter of funding.)

-

Steven: In October, how would the project be funded to meet your deadlines?

-

Olivia: Out of our capital budget.

-

Steven: How much has been allocated for this project?

-

Olivia: We have set aside $1,080,000.

-

Steven: How did you establish that figure? (He wants to see if she used a competitor's estimate to arrive at a dollar amount.)

-

Olivia: Ron feels that we need at least a three-year payback to proceed. Being good with numbers, you have probably figured out that it's the potential $360,000 savings times three years. (Steven will use his next question to link Olivia's measurable response to the filter of past keys.)

-

Steven: What is the major reason why you approved or abandoned projects involving reducing downtime in the past?

-

Olivia: We stopped pursuing a project last year with one of your competitors because we didn't feel confident that their products would work in our situation.

-

Steven: What does it take for you to feel assured that a solution will work in your circumstances? (Again, Steven does not want to get into a negative sale. Rather, he wants to find out what it will take to avoid his competitor's mistake and make sure that Olivia knows the reasons. If she doesn't, Steven will need to rethink and question what her role really is, and her importance in the decision-making process.)

-

Olivia: We want to make sure they understand the nuances of our operations and demonstrate where their products work in similar situations. (Olivia's answer, while clearer, still needs further clarification.)

-

Steven: What would meet those requirements? (This question requires Olivia to provide specific details.)

-

Olivia: We would want a company to conduct an engineering survey of our equipment operations and provide documented results they achieved over a two-year period with one of our competitors. (Steven will use his next question to link Olivia's measurable response to the most important filter, which is attainment measurement. With all the details discussed, Steven asks Olivia to review his summary on how she knows if she achieves her goal of reducing downtime. He wants to make sure nothing major is missing. Steven looks at his notes and begins.)

-

Steven: Let me see if I understand what you said it will take to achieve your goal of minimizing downtime. You want to reduce your costs of $40,000 per downtime hour to no more than nine hours annually, save $360,000, begin in November and finish by December, not exceed $1,080,000 budget, get at least a three-year payback, and any solution must have proven performance. Is there anything that we missed? (I'm glad that I took notes.)

-

Olivia: If we can accomplish all that, there will be a lot of happy people here. Do you think you have any products that can do what we want to do?

-

Steven: Before I say a definite yes, I'd like to take everything we discussed today and run it past my engineering group to get their thoughts. Does that sound like a good plan to you? (Steven is positive that he can help Olivia. However, he sticks to his MP 2 strategy. His objective is to gather details about goals and filters, review them with his sales and engineering team, and see if he needs more information. Furthermore, he wants to obtain MPC 2: Potential Confirmed via a conditional commitment, match features to measurable benefits in MP 3: Cement Solution, and only then make his presentation. Discipline will have its rewards.)

Step Four: Yellow Light

Do a summary of the measurable benefits of the customer's goals to build momentum. Get her head nodding in approval. You are ready to have the customer separate the serious car buyers from the tire kickers.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 170