The Middle Period

Kram's middle period lasts for two to five years and is regarded as the most rewarding for the two parties. The relationship is cultivated as the mentor coaches and promotes his or her mentee. The friendship between the two strengthens as a high degree of trust and intimacy builds up between the mentor and mentee.

The mentor's ability to coach the mentee and clarify his or her sense of purpose and identity helps to improve the mentee's sense of self-worth. In sponsoring mentoring, the mentor provides the mentee with work opportunities that help to develop his or her managerial skills and confirm and reinforce the mentee's sense of competence and ability. The mentee understands the business scenario better and knows how better to control the work environment.

One mentee commented:

I was very under-confident when I joined this company. I was newly divorced and I had not worked for quite some time. I was wholly intimidated by the business world. My mentor encouraged me to perform beyond my job description. She would criticise my performance, explain my mistakes and advise me on how to perform better. Above all, she gave me confidence. She would say ‘I know that you have the ability to do it, and I know that you will do it. ' Her encouragement and faith in me was a great support and incentive.

It is at this stage that the mentor gains the most satisfaction from the knowledge that he or she has had an important effect on the mentee's development. One mentor tries to describe the pride he feels when he sees his mentee perform well and receive recognition from the company:

The satisfaction I receive is similar to parental pride. You have put faith in that person and helped them develop. When they succeed, you feel it has all been worthwhile and you remember that you were instrumental in helping them to do so.

Mentors also receive technical and psychological help and support from their mentees. The mentee now has the skill to help his or her mentor as well as the ability to recognise the needs of the more senior manager. The mentor has a renewed sense of his or her own influence and power as he or she opens doors in the organisation for the mentee. The mentor also feels that he or she is passing something to the company that will have lasting value. Through the mentee the sponsoring mentor can express his or her own perspectives and values.

In Kram's scenario, it often takes until this point for the mentor and the mentee to have agreed upon a set of development goals or even a career path, involving at least one and usually several clearly defined promotional or horizontal moves. Discussions between the mentor and mentee now centre less on defining objectives than on strategies and tactics to achieve them. Project work that the line manager mentor sets his or her mentee is aimed both at developing skills and at assessing how well they have been absorbed. The two people meet regularly to review progress in each area where they have agreed improvement is necessary to qualify for the next career step. The mentor directs the mentee towards additional sources of learning and challenges him or her to prove the successes claimed.

Again the picture that emerges from developmental mentoring is different in a number of ways. For a start, the time horizon is often much shorter - many developmental mentoring relationships are well into the middle (or the progress-making) period after six months or so. Second, the mentor has no role in the projects or tasks the mentee undertakes, other than as a sounding-board. Third, the developmental mentoring relationship at this stage is characterised by a much deeper level of challenge, probing and analysis. Fourth, the mentee begins to rely much more on his or her own judgement, and is less likely to seek the mentor's approval.

Finally, the mentor often learns as much or more from their dialogue as does the mentee. This highly fulfilling phase of the relationship often settles down to a routine in which the pair are sufficiently familiar and comfortable with the process to explore more and more ‘difficult' issues. Sensitive areas that the mentee has avoided now become admissible and may provide the deepest and most transforming issues for discussion.

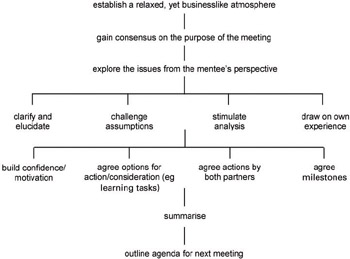

Throughout this whole progress-making phase, the effective mentor demonstrates a remarkably consistent skill set - consistent, that is, with every other effective mentor. Figure 14 is based on observation of numerous mentors, ranging from the very effective to the very ineffective.

Figure 14: The mentoring meeting

The most effective mentors, even those who are strongly activist and/or task-oriented, always start the process by re-establishing rapport. For a few minutes they engage in the normal social trivialities that help people relax in each other's company. Then they ask the mentee to explain briefly what issues he or she would like to explore. One of my favourite questions to executive mentees is, ‘What's keeping you awake at night this week?'

Ineffective mentors listen briefly to the mentee's account and immediately relate the issue to their own experience, when they perceive it to be relevant. They tell the mentee what happened to them, how they tackled the issue, and what lessons they learned. As a result, they frequently end up advising on the presented issue, missing deeper, more important issues. Effective mentors hold fire. First, they ask for more facts and feelings - what exactly happened? How did you feel about it? Is this a one-off occurrence?

Next, they challenge the assumptions behind the mentee's account - for example, what would an unbiased third party have thought if they were observing? The responses to this probing, and the different perspectives generated, allow mentor and mentee to analyse the situation in some form of conceptual framework. For example, ‘Let's look at how your behaviour might be influencing your colleagues, and vice versa. '

Finally, in this first half of the mentoring session, the mentor may draw upon his or her own experience to introduce additional considerations.

Having understood the issues better, mentor and mentee can concentrate on developing pragmatic solutions. Before launching into problem-solving mode, however, the mentor ensures that the mentee is in a sufficiently positive frame of mind - that he or she has the confidence to consider alternative approaches and the commitment to making a change happen. Through a variety of techniques, the mentor helps the mentee catalogue possible ways forward and assess them against the mentee's own values criteria. Having selected one or two to pursue, the pair agree who will do what in dealing with the issue. Ineffective mentors sometimes tend to take on extensive responsibilities; effective ones limit their role to tasks such as seeking out an article or report, or making an introduction. The effective mentor also presses the mentee to set mental deadlines by which he or she expects to have tackled at least the initial stages of the plan.

One final task remains - summarising what has been discussed. Ineffective mentors rush straight in and summarise for the mentee. In doing so, they both miss the chance to check that there is a common understanding and take responsibility for the issue at least partly back on to their own shoulders. Effective mentors ensure that the mentee summarises and retains ownership of the issue throughout, including whether to bring the matter back to the agenda next time they meet.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 124